Ruth Guggenheimer> November 1933

0 Ruth Guggenheimer

Farewell in Lindau. Ruth Guggenheimer and the end of the German-Jewish dream

Lindau, November 1933

With the transfer of power to the National Socialists in Germany, nationalism became the dream of world domination - and widespread anti-Semitism, whether traditionally anti-Judaic or racist, became a state ideology of world redemption. Thousands of political opponents of the Nazis, well-known writers and intellectuals, as well as Jews, fled to neighboring countries of the German Reich as early as 1933, to Austria, France or the Netherlands, even to fascist Italy and not least to Switzerland. In Basel alone, 7500 emigrants arrive in 1933. Lindau also became a place of escape, with people fleeing across Lake Constance to Switzerland.

In the fall of 1933, Ruth Guggenheimer also leaves her hometown of Memmingen. Her parents ran a widely respected horse trading business there in the Allgäu region. After attending business school in Munich, she herself worked as a secretary in Memmingen. However, she lost her job after the Nazis came to power. Most Jews in Germany still believe that this time will pass. But in the summer, Ruth Guggenheimer decided to emigrate. She is 23 years young and wants to take her life into her own hands.

Many years later, in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, she will write down her memories like a novel. She doesn't dwell on historical details and changes her name. She wants to tell a story that is not just about herself.

She also doesn't talk about the difficulties of getting the necessary papers for her emigration. But she does describe her departure and her journey to freedom, via Lindau and Lake Constance.

On a gray November day, she stands with her parents at the train station in Memmingen.

“She has said goodbye to all her friends and has kept quiet about the day of her departure. The suitcases are checked in, only Resi came with her onto the platform carrying her small luggage. She can't hold back the tears. “Resi, I'll come and visit you in a few years and you'll make me chocolate pudding,” Renate encourages her.

Finally the time has come, the stationmaster with the red cap signals the departure. Renate has squeezed herself into the corner of the compartment. Her parents accompany her to Lindau, from where she continues on her own across Lake Constance.

“Don't you at least want to look out, take one last look at your hometown,” Oskar Gundelfinger asks his daughter. “No, I don't need to look out, I'll take my home with me in my heart,” she replies more curtly than she intended.

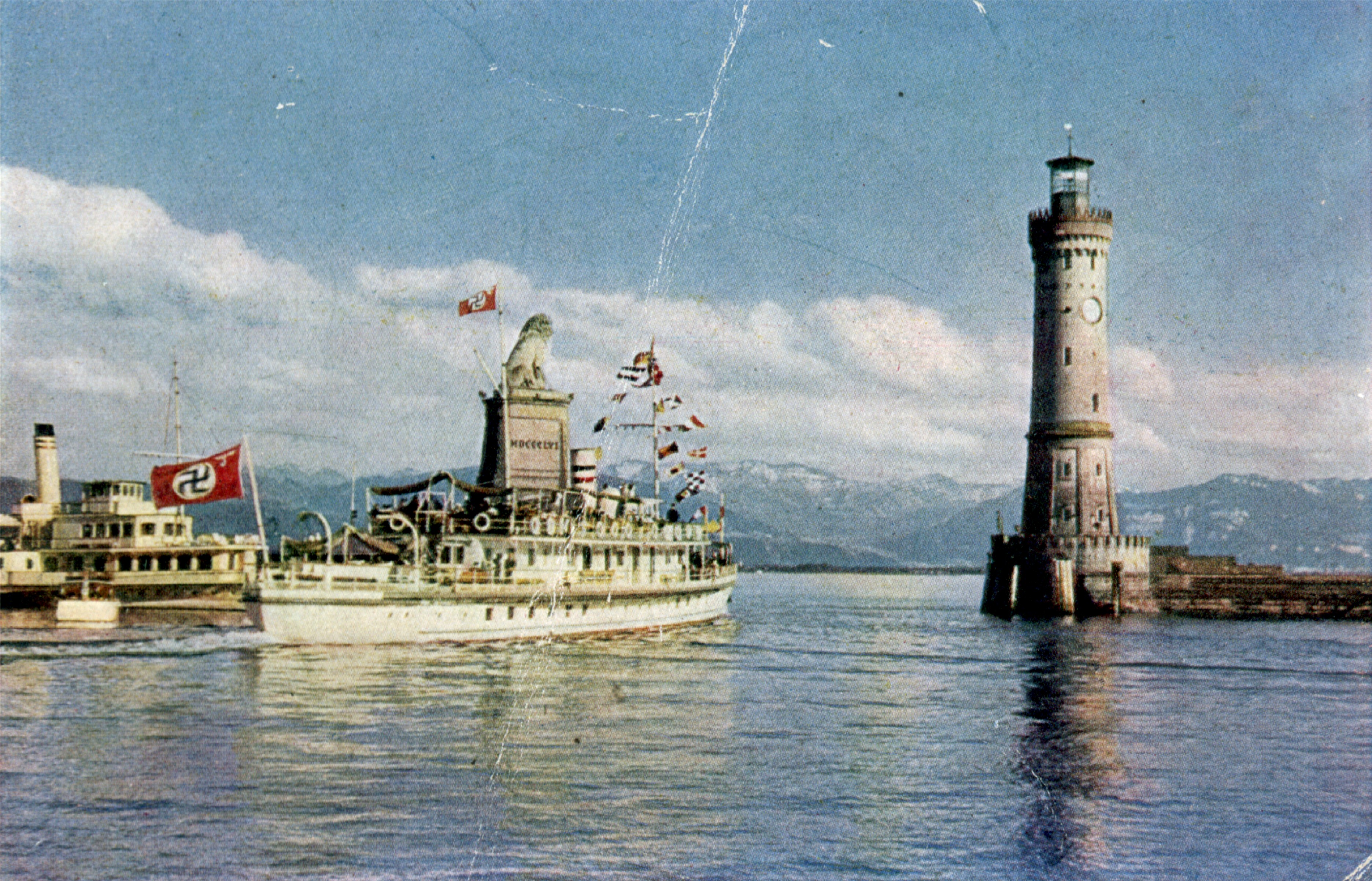

The journey to Lindau takes place in a depressed mood. Renate has to keep looking at her parents' beloved faces. The last six months have left their mark on them. In Lindau they spend another evening overshadowed by sadness, and the next morning it is time to say goodbye. ... White wisps of cloud drift over the harbor, enveloping the lighthouse and the lion. The seagulls swoop down onto the water with shrill cries to get their food. The Swiss ship rocks restlessly on the waves. Finally Renate has passed the passport control and body search. They want to make it easier for me to leave, she thinks as she stands at the railing of the small ship on Swiss soil. Her parents look up at her from the quay, two lonely people, marked by suffering. The ship slowly maneuvers its way through the narrow harbour exit.

Renate can see nothing. Tears burn hot in her eyes and run irresistibly down her face. They mingle with the wisps of mist that envelop the ship, the lighthouse and her homeland.”

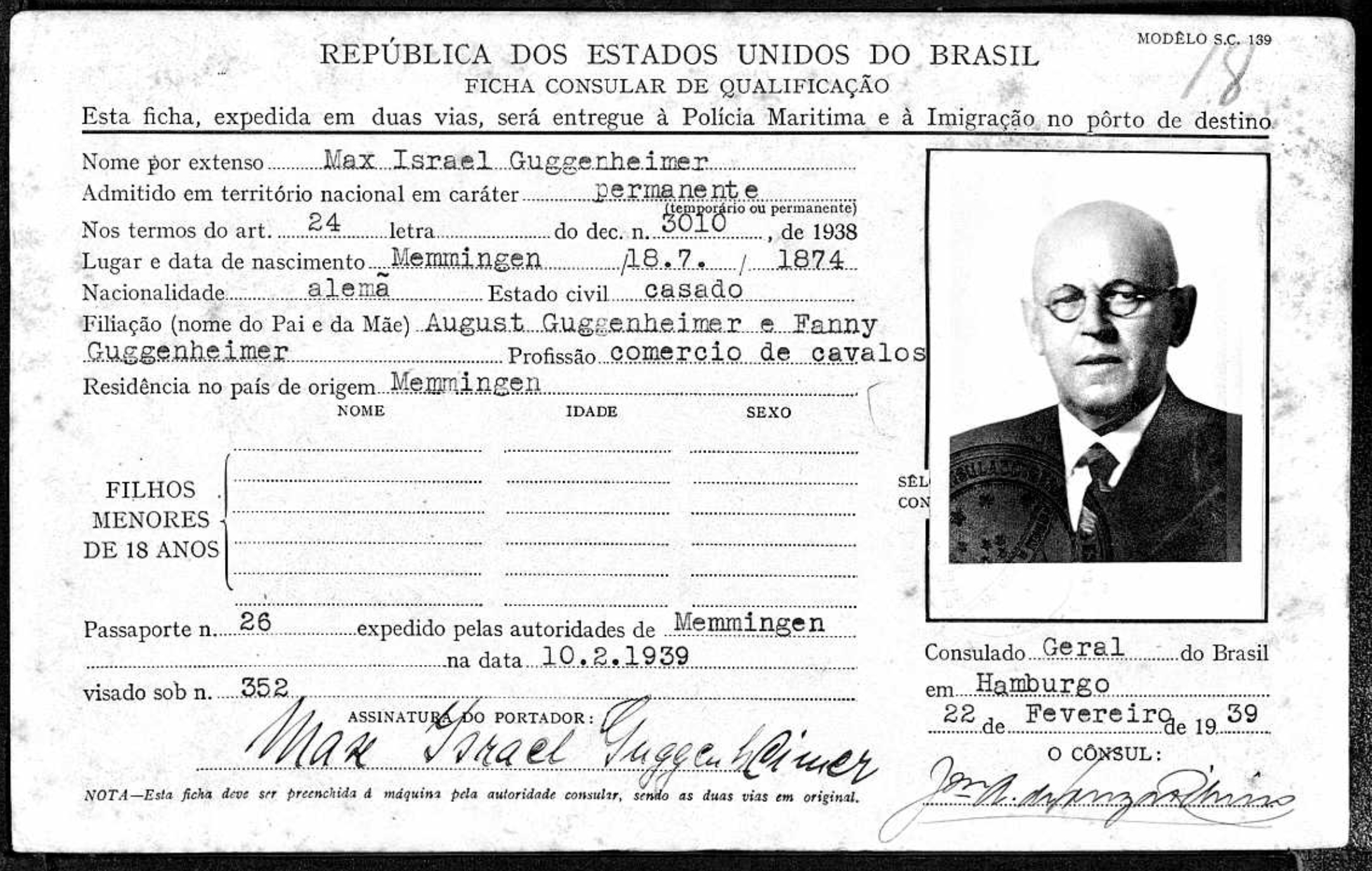

Ruth Guggenheimer goes to Brazil via Switzerland and France. En route in Paris, she marries Ernst Weikersheimer. In Rio de Janeiro, she begins her second life with her new family and she actually succeeds in bringing her parents to Brazil.[1]

[1] A passage from Ruth Weikersheimer: „Eine Jugend in Memmingen. Zwischen gestern und morgen…“, in: Gernot Römer, Schwäbische Juden. Leben und Leistungen aus zwei Jahrhunderten. Augsburg 1990, p. 197f.

0 Ruth Guggenheimer

Farewell in Lindau. Ruth Guggenheimer and the end of the German-Jewish dream

Lindau, November 1933

With the transfer of power to the National Socialists in Germany, nationalism became the dream of world domination - and widespread anti-Semitism, whether traditionally anti-Judaic or racist, became a state ideology of world redemption. Thousands of political opponents of the Nazis, well-known writers and intellectuals, as well as Jews, fled to neighboring countries of the German Reich as early as 1933, to Austria, France or the Netherlands, even to fascist Italy and not least to Switzerland. In Basel alone, 7500 emigrants arrive in 1933. Lindau also became a place of escape, with people fleeing across Lake Constance to Switzerland.

In the fall of 1933, Ruth Guggenheimer also leaves her hometown of Memmingen. Her parents ran a widely respected horse trading business there in the Allgäu region. After attending business school in Munich, she herself worked as a secretary in Memmingen. However, she lost her job after the Nazis came to power. Most Jews in Germany still believe that this time will pass. But in the summer, Ruth Guggenheimer decided to emigrate. She is 23 years young and wants to take her life into her own hands.

Many years later, in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, she will write down her memories like a novel. She doesn't dwell on historical details and changes her name. She wants to tell a story that is not just about herself.

She also doesn't talk about the difficulties of getting the necessary papers for her emigration. But she does describe her departure and her journey to freedom, via Lindau and Lake Constance.

On a gray November day, she stands with her parents at the train station in Memmingen.

“She has said goodbye to all her friends and has kept quiet about the day of her departure. The suitcases are checked in, only Resi came with her onto the platform carrying her small luggage. She can't hold back the tears. “Resi, I'll come and visit you in a few years and you'll make me chocolate pudding,” Renate encourages her.

Finally the time has come, the stationmaster with the red cap signals the departure. Renate has squeezed herself into the corner of the compartment. Her parents accompany her to Lindau, from where she continues on her own across Lake Constance.

“Don't you at least want to look out, take one last look at your hometown,” Oskar Gundelfinger asks his daughter. “No, I don't need to look out, I'll take my home with me in my heart,” she replies more curtly than she intended.

The journey to Lindau takes place in a depressed mood. Renate has to keep looking at her parents' beloved faces. The last six months have left their mark on them. In Lindau they spend another evening overshadowed by sadness, and the next morning it is time to say goodbye. ... White wisps of cloud drift over the harbor, enveloping the lighthouse and the lion. The seagulls swoop down onto the water with shrill cries to get their food. The Swiss ship rocks restlessly on the waves. Finally Renate has passed the passport control and body search. They want to make it easier for me to leave, she thinks as she stands at the railing of the small ship on Swiss soil. Her parents look up at her from the quay, two lonely people, marked by suffering. The ship slowly maneuvers its way through the narrow harbour exit.

Renate can see nothing. Tears burn hot in her eyes and run irresistibly down her face. They mingle with the wisps of mist that envelop the ship, the lighthouse and her homeland.”

Ruth Guggenheimer goes to Brazil via Switzerland and France. En route in Paris, she marries Ernst Weikersheimer. In Rio de Janeiro, she begins her second life with her new family and she actually succeeds in bringing her parents to Brazil.[1]

[1] A passage from Ruth Weikersheimer: „Eine Jugend in Memmingen. Zwischen gestern und morgen…“, in: Gernot Römer, Schwäbische Juden. Leben und Leistungen aus zwei Jahrhunderten. Augsburg 1990, p. 197f.