Claus Magen and Hanns-Gerd Schünzel> March 12, 1940

6a Claus Magen und Hanns-Gerd Schünzel

Uneven oars and a leak in the hull: two young men from Dresden fail during their escape on Lake Constance

Hard, March 12, 1940

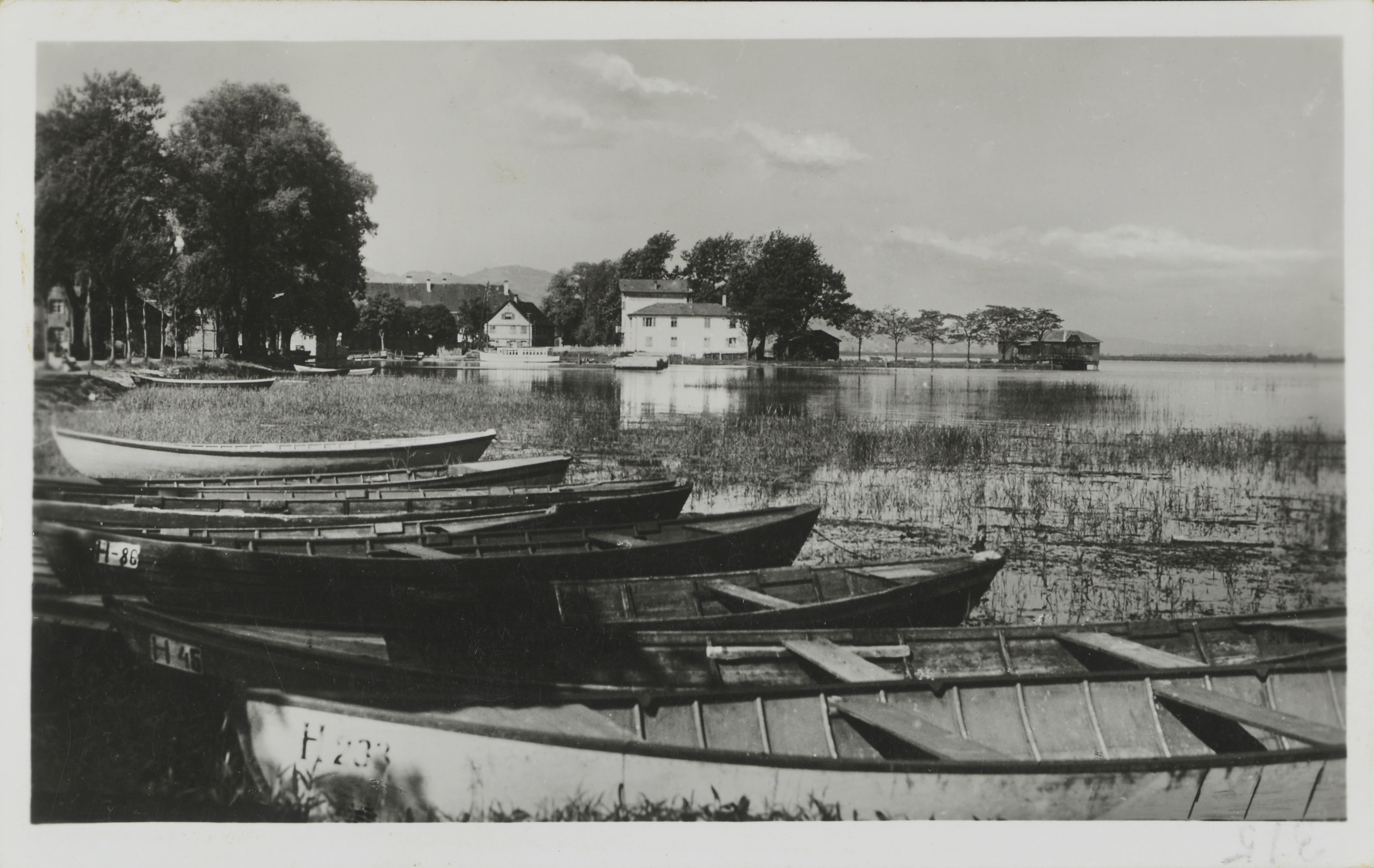

When Claus Magen and Hanns-Gerd Schünzel reach the shores of Lake Constance – after a one-and-a-half-day train journey from Dresden via Munich and Bregenz - Switzerland, their chosen destination, already seems very close. The view presented to the two sixteen-year-olds on the afternoon of March 12, 1940, was very different from the situation today. The Green Dam and therefore also the inland basin would not be built until almost thirty years later. And the mouth of the New Rhine, completed in 1900, did not yet protrude far into the lake. And so only the Rohrspitz, the last headland in Vorarlberg, obstructed the straight crossing to the border at the Old Rhine. Only a few meters away from the steps of the parish church, the first boats were moored in the Harder Bay.

Claus Magen and Hanns-Gerd Schünzel, almost the same age, had met just a year earlier in a church in Dresden – the 'American Church of St. John'. Schünzel was deeply committed to his faith and took part in Sunday services as an altar boy. As a student he aspired to study theology in the USA. However, the start of the war in September 1939 put apparently insurmountable obstacles in the way of these plans. The young man could no longer count on an exit permit. The only option left was to cross the border illegally. In the end, he also involved his friend Claus Magen in this plan. As the son of the Jewish pharmacist Kurt Magen, he had his own reason to leave the country. The fact that the family had long since converted to the Protestant faith meant nothing to the Nazis. For three years, Claus Magen had attended a boarding school on the Rosenberg in St. Gallen. But in September 1938, his father was informed by the foreign exchange office that his account was blocked for transfers abroad and that school fees could no longer be transferred to Switzerland.

At the end of October 1938, fourteen-year-old Claus Magen had to return to Dresden, just in time to witness his father's arrest and deportation to Buchenwald on November 10.[1] Initially released after three weeks, his father was arrested again a year later after the Munich attempt on Hitler's life, along with hundreds of other innocent people. In the meantime, Claus Magen had turned 16 years old and was determined to take his fate into his own hands. Before going to church on Sunday, March 3, 1940, he and Schünzel agreed to flee. A week later, they set off by train. They traveled separately to Munich, then together to Lindau, where they spent the night at the Hotel Peterhof.

On the morning of March 12, they promptly fail their first attempt to cross the lake. Schünzel and Magen found only boats without oars and so at midday they boarded another train, this time to Bregenz. They now hope to reach the border by land. Their walk takes them to an inn in Hard on the lake. There, however, they learn that there are strict controls at the nearby bridge over the new Rhine. It seems impossible to continue without the appropriate papers. So they decide to try their luck across the lake again. Two days later, they report the story of their failure to the border police in Bregenz.

“After we had finished our meal, we went to the village of Hard and put our rucksacks down at the ‘Zum Löwen’ inn. Then we went to the lake to look for a boat. On the lakeshore opposite the church we also saw [...] a boat lying there, but again the oars were missing.”[2]

Only after dark do they manage to steal two oars outside the 'Zur Traube' inn. But they didn't get far with the boat they had scouted out in advance, even on their second attempt:

“We then got it into the water with difficulty and initially kept going around in circles because the oars were too uneven. After a while, when a searchlight went over the lake around where we were, and the boat started to leak, we went back to shore, as it seemed hopeless to continue.”[3]

Back ashore, Magen and Schünzel soon encounter new, insurmountable obstacles. They manage to cross a narrow canal, but soon find themselves at the outlet of the Dornbirner Ach and realize that the only way to get there is over the bridge upstream. There they run into the checkpoint and are arrested at midnight.

Hanns-Gerd Schünzel manages to throw away the revolver he had been carrying without really knowing what to do with it. The gun is found, but they are lucky. It is believed that it had not been used.

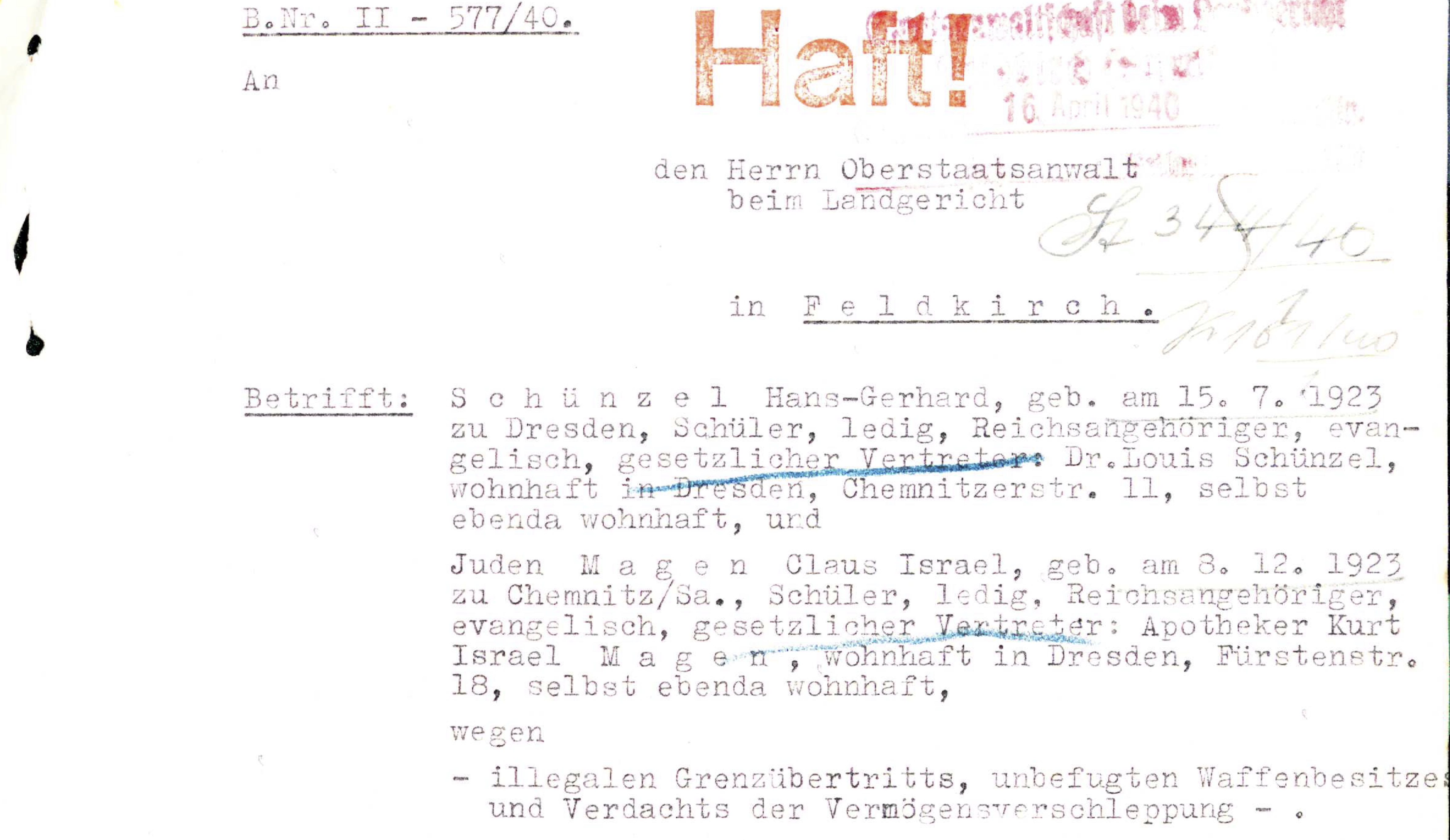

Two months after their arrest, the two minors are now found guilty before the Feldkirch juvenile court. Their integrity and their confession were recognized as mitigating circumstances and the two were sentenced to only three weeks in prison. As the time already served in custody is taken into account, Magen and Schünzel are released.[4] A deceptive freedom that did not last long for either of them. Hanns-Gerd Schünzel soon found himself in a Wehrmacht uniform at the age of 18. Stationed with his infantry replacement battalion in Tarvisio, Italy, he took his own life on May 22, 1942.

However, Claus Magen's story - and that of his family - is recorded in the legendary diary of Victor Klemperer, the Dresden literary scholar and later GDR politician.

On May 26, 1942, Klemperer noted:

“I often heard the name of a Jewish pharmacist Magen mentioned. The man was arrested several times. His [...] son fled when he was supposed to be evacuated and apparently escaped. That was in January. Then the father, a man in his fifties, was arrested again [...]. - Yesterday Kätchen tells me: ‘Magen died.’ - One more murder!”[5]

It is not known exactly where Claus Magen spent the first few months of 1942. On April 7, 1942, his name can be found in the prisoner records of the Leipzig police headquarters. He spent one night in custody there before being transferred to the Dresden police prison. He was brought in from Lörrach, the German town on the Swiss border near Basel. His last escape attempt there was probably unsuccessful. Victor Klemperer wrote about his fate again in his diary on August 29, 1942:

“The boy [...] fled when he was supposed to be sent to Riga in January. The father was taken to prison, the boy was caught and taken to a concentration camp. The father died in prison a few months ago. The boy these days in the concentration camp. Cause of death 'stomach and intestinal catarrh'. Since when does a strong young person die of this? Either typhoid fever or no doctor or injection.”[6]

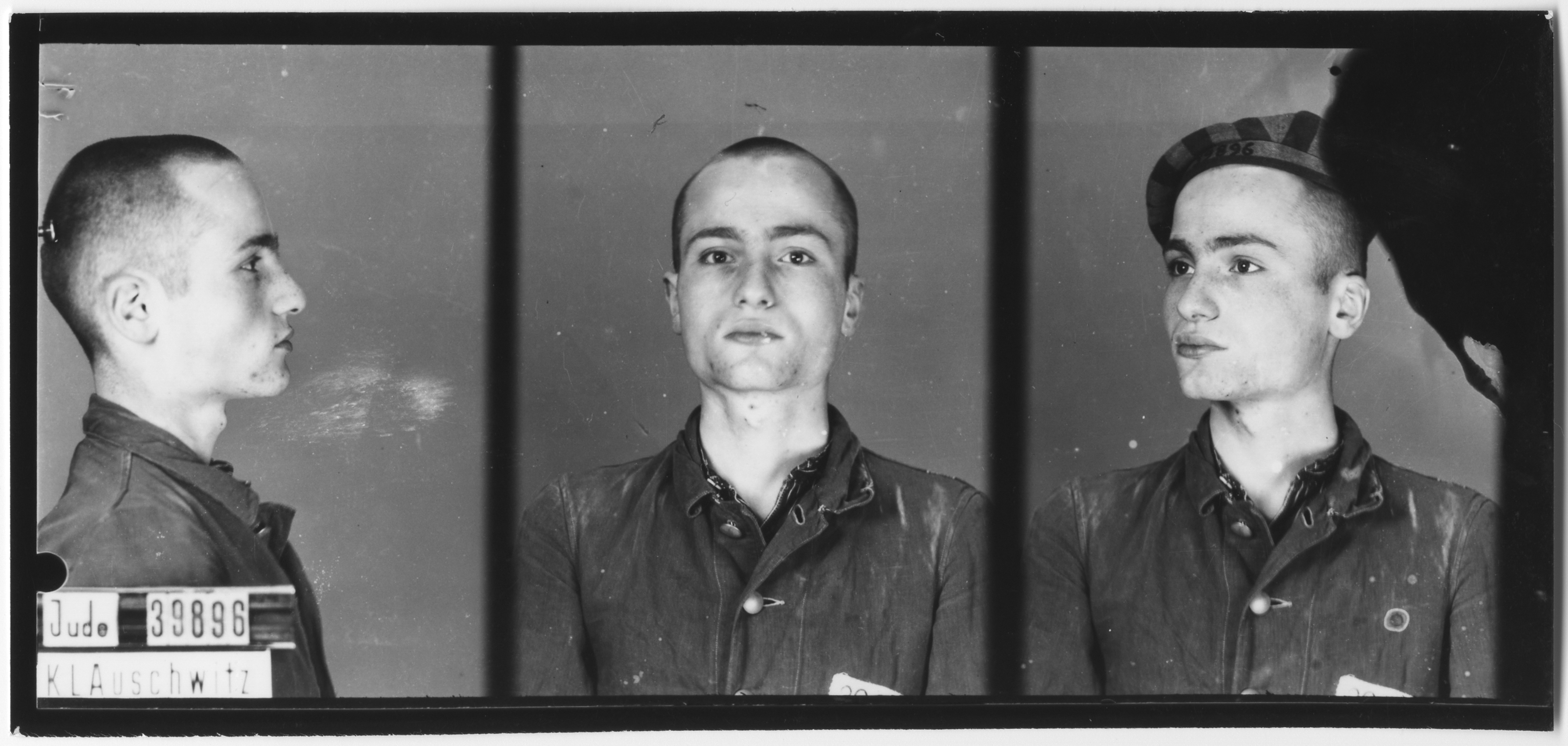

However: On the night of August 16-17, 1942, Claus Magen was put to death in the Auschwitz extermination camp.

[1] Written statements by Kurt Magen, which were intended for the defense of his son Claus Magen during the court proceedings on 10 May 1940. Kurt Magen was unable to attend the main hearing, it is not known whether his letter was read out, it is not mentioned in the minutes in the course of the evidentiary proceedings. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, pages 90f resp. 101ff.

[2] Transcript of the court hearing Claus Joachim Eduard Magen, Bregenz, 15 March 1940, p. 4. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, page 42.

[3] Transcript oft he questioning of Hans-Gerhard Schünzel, Bregenz March 14, 1940, p. 5. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, page 36.

[4] Protocol of the trial on May 10, 1940 at the juvenile court Feldkirch. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, pages 101ff.

[5] Walter Nowojski (Hrsg.), Victor Klemperer. Tagebücher 1942, nach: Victor Klemperer, Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten, Berlin 1999, S. 98.

6a Claus Magen und Hanns-Gerd Schünzel

Uneven oars and a leak in the hull: two young men from Dresden fail during their escape on Lake Constance

Hard, March 12, 1940

When Claus Magen and Hanns-Gerd Schünzel reach the shores of Lake Constance – after a one-and-a-half-day train journey from Dresden via Munich and Bregenz - Switzerland, their chosen destination, already seems very close. The view presented to the two sixteen-year-olds on the afternoon of March 12, 1940, was very different from the situation today. The Green Dam and therefore also the inland basin would not be built until almost thirty years later. And the mouth of the New Rhine, completed in 1900, did not yet protrude far into the lake. And so only the Rohrspitz, the last headland in Vorarlberg, obstructed the straight crossing to the border at the Old Rhine. Only a few meters away from the steps of the parish church, the first boats were moored in the Harder Bay.

Claus Magen and Hanns-Gerd Schünzel, almost the same age, had met just a year earlier in a church in Dresden – the 'American Church of St. John'. Schünzel was deeply committed to his faith and took part in Sunday services as an altar boy. As a student he aspired to study theology in the USA. However, the start of the war in September 1939 put apparently insurmountable obstacles in the way of these plans. The young man could no longer count on an exit permit. The only option left was to cross the border illegally. In the end, he also involved his friend Claus Magen in this plan. As the son of the Jewish pharmacist Kurt Magen, he had his own reason to leave the country. The fact that the family had long since converted to the Protestant faith meant nothing to the Nazis. For three years, Claus Magen had attended a boarding school on the Rosenberg in St. Gallen. But in September 1938, his father was informed by the foreign exchange office that his account was blocked for transfers abroad and that school fees could no longer be transferred to Switzerland.

At the end of October 1938, fourteen-year-old Claus Magen had to return to Dresden, just in time to witness his father's arrest and deportation to Buchenwald on November 10.[1] Initially released after three weeks, his father was arrested again a year later after the Munich attempt on Hitler's life, along with hundreds of other innocent people. In the meantime, Claus Magen had turned 16 years old and was determined to take his fate into his own hands. Before going to church on Sunday, March 3, 1940, he and Schünzel agreed to flee. A week later, they set off by train. They traveled separately to Munich, then together to Lindau, where they spent the night at the Hotel Peterhof.

On the morning of March 12, they promptly fail their first attempt to cross the lake. Schünzel and Magen found only boats without oars and so at midday they boarded another train, this time to Bregenz. They now hope to reach the border by land. Their walk takes them to an inn in Hard on the lake. There, however, they learn that there are strict controls at the nearby bridge over the new Rhine. It seems impossible to continue without the appropriate papers. So they decide to try their luck across the lake again. Two days later, they report the story of their failure to the border police in Bregenz.

“After we had finished our meal, we went to the village of Hard and put our rucksacks down at the ‘Zum Löwen’ inn. Then we went to the lake to look for a boat. On the lakeshore opposite the church we also saw [...] a boat lying there, but again the oars were missing.”[2]

Only after dark do they manage to steal two oars outside the 'Zur Traube' inn. But they didn't get far with the boat they had scouted out in advance, even on their second attempt:

“We then got it into the water with difficulty and initially kept going around in circles because the oars were too uneven. After a while, when a searchlight went over the lake around where we were, and the boat started to leak, we went back to shore, as it seemed hopeless to continue.”[3]

Back ashore, Magen and Schünzel soon encounter new, insurmountable obstacles. They manage to cross a narrow canal, but soon find themselves at the outlet of the Dornbirner Ach and realize that the only way to get there is over the bridge upstream. There they run into the checkpoint and are arrested at midnight.

Hanns-Gerd Schünzel manages to throw away the revolver he had been carrying without really knowing what to do with it. The gun is found, but they are lucky. It is believed that it had not been used.

Two months after their arrest, the two minors are now found guilty before the Feldkirch juvenile court. Their integrity and their confession were recognized as mitigating circumstances and the two were sentenced to only three weeks in prison. As the time already served in custody is taken into account, Magen and Schünzel are released.[4] A deceptive freedom that did not last long for either of them. Hanns-Gerd Schünzel soon found himself in a Wehrmacht uniform at the age of 18. Stationed with his infantry replacement battalion in Tarvisio, Italy, he took his own life on May 22, 1942.

However, Claus Magen's story - and that of his family - is recorded in the legendary diary of Victor Klemperer, the Dresden literary scholar and later GDR politician.

On May 26, 1942, Klemperer noted:

“I often heard the name of a Jewish pharmacist Magen mentioned. The man was arrested several times. His [...] son fled when he was supposed to be evacuated and apparently escaped. That was in January. Then the father, a man in his fifties, was arrested again [...]. - Yesterday Kätchen tells me: ‘Magen died.’ - One more murder!”[5]

It is not known exactly where Claus Magen spent the first few months of 1942. On April 7, 1942, his name can be found in the prisoner records of the Leipzig police headquarters. He spent one night in custody there before being transferred to the Dresden police prison. He was brought in from Lörrach, the German town on the Swiss border near Basel. His last escape attempt there was probably unsuccessful. Victor Klemperer wrote about his fate again in his diary on August 29, 1942:

“The boy [...] fled when he was supposed to be sent to Riga in January. The father was taken to prison, the boy was caught and taken to a concentration camp. The father died in prison a few months ago. The boy these days in the concentration camp. Cause of death 'stomach and intestinal catarrh'. Since when does a strong young person die of this? Either typhoid fever or no doctor or injection.”[6]

However: On the night of August 16-17, 1942, Claus Magen was put to death in the Auschwitz extermination camp.

[1] Written statements by Kurt Magen, which were intended for the defense of his son Claus Magen during the court proceedings on 10 May 1940. Kurt Magen was unable to attend the main hearing, it is not known whether his letter was read out, it is not mentioned in the minutes in the course of the evidentiary proceedings. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, pages 90f resp. 101ff.

[2] Transcript of the court hearing Claus Joachim Eduard Magen, Bregenz, 15 March 1940, p. 4. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, page 42.

[3] Transcript oft he questioning of Hans-Gerhard Schünzel, Bregenz March 14, 1940, p. 5. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, page 36.

[4] Protocol of the trial on May 10, 1940 at the juvenile court Feldkirch. See: VLA Landesgericht Feldkirch Vr-161/1940, pages 101ff.

[5] Walter Nowojski (Hrsg.), Victor Klemperer. Tagebücher 1942, nach: Victor Klemperer, Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten, Berlin 1999, S. 98.