Felix Granichstaedten, Wilhelm Huber, Rubin Markowitz> August 17, 1938

17a Felix Granichstaedten, Wilhelm Huber, Rubin Markowitz.

Vienna, Diepoldsau, France and then?

Hohenems/Diepoldsau, August 17, 1938

In Bern, Heinrich Rothmund, head of the immigration police, summoned the cantonal police directors. On the same day, August 17, 1938, at least 37 refugees arrive in Diepoldsau from Vienna. In total, over 200 people fled to Switzerland via Hohenems and the old Rhine in that week alone. The main concern there is how to get rid of them again.

One of the refugees crossing the border that very day is Felix Hans Granichstaedten, the son of a well-known Viennese composer of operettas. The young man, a baptized Catholic like his father, had already experienced a few adventures. Born in Prague in 1919, he caused his parents quite a few headaches. In 1933, at the age of just fourteen, he ran away from home, hung around with some ruffians and was picked up a few days later in Pressbaum. The Viennese tabloids gleefully exploited the scandal. An apprenticeship as a mechanic was supposed to put him on the right track; then he worked in a department store, and attempted suicide.

In 1938, however, he had every reason to run away. The Granichstaedtens were now nothing but Jews in the eyes of the National Socialist authorities. In that same year his father, Bruno Granichstaedten, who had already spent some time in Hollywood in 1932, managed to escape – now married to his second wife – via Luxembourg to the US.

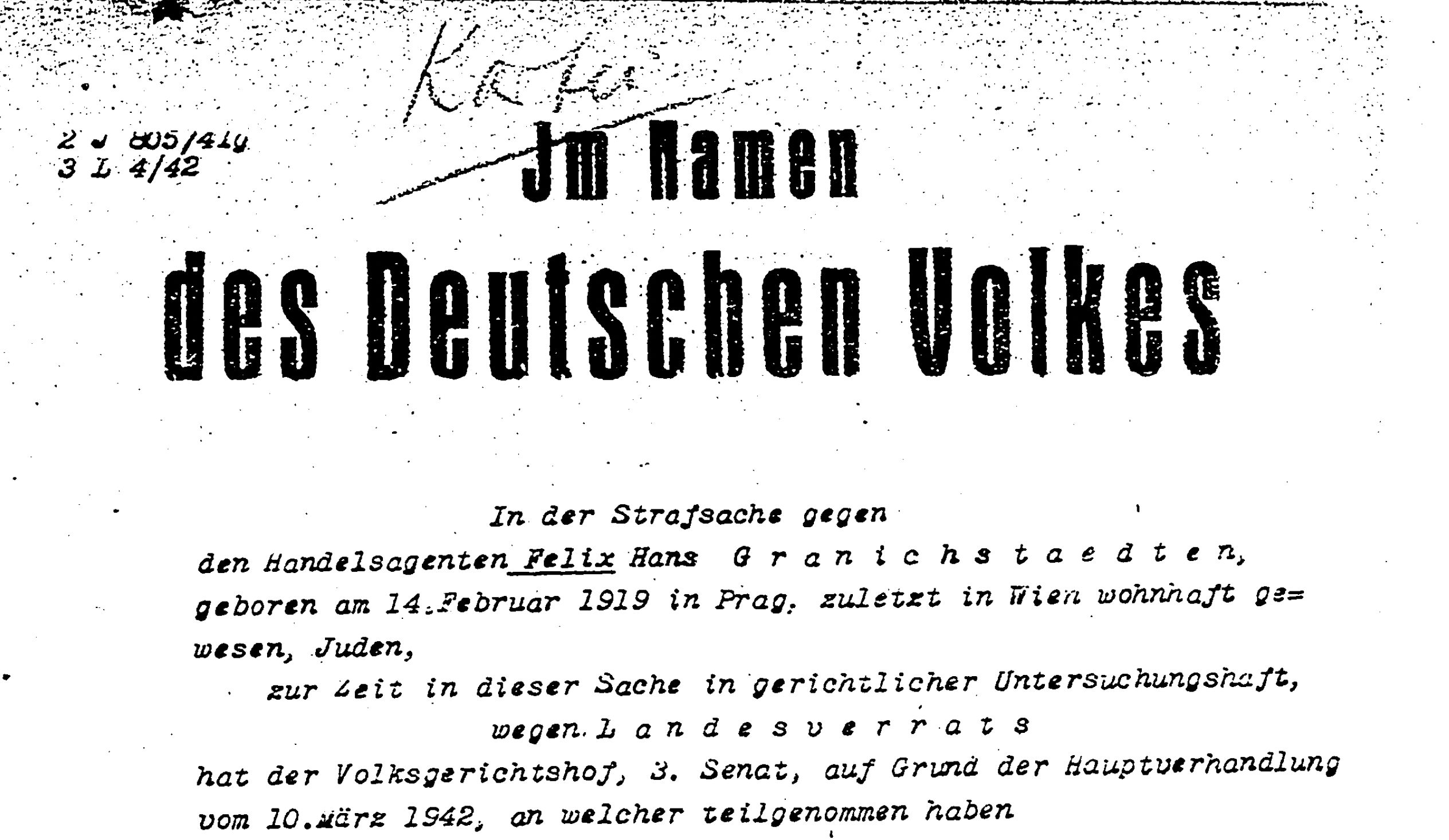

Felix Granichstaedten, however, found himself before the People's Court of the German Reich in Berlin on March 10, 1942. Charged with treason. How he got there from Diepoldsau is meticulously explained in the verdict for seven years in prison. It is a verdict that sounds almost sympathetic given the circumstances of National Socialism, but it will certainly not help him.

“After the annexation of the Ostmark to the Reich [...] the accused decided to emigrate because he did not want to remain in Germany as a Jew. On August 17, 1938, he traveled from Vienna to Vorarlberg and crossed the green border to Switzerland. Here he lived for about nine months in an emigrant camp in Diepoldsau. Then, as a Catholic, he was supported by the Caritas association and accommodated with a Catholic family near St. Gallen. From October 1939 he was taken in by the family of a lower post office official out of compassion, although there were already 9 children in the house. The accused, who did not have a work permit, tried to earn a small income by repairing radio sets. He was therefore summoned by the police, cautioned for working without a permit and referred to the Austrian and Foreign Legions in France.”[1]

But it was precisely this 'clue' that proved to be Granichstaedten's undoing. Apparently, even the judges who decide his fate still feel sorry for the young man. The story continues:

“The defendant, who had no prospect of getting a work permit and work in Switzerland, but who on the other hand no longer wanted to be a burden on the family that had taken him in, decided to go to France and join the Foreign Legion.”[2]

He was given a ticket by Swiss Caritas. Having crossed the borderin February 1940 he was awaited by the French Guard. He received his training in Sidi bel Abbès in Algeria. And after the capitulation of France in June, he finally enlisted in a work company in the fall, also in Algeria, becoming an electrician in the machine center of a coal mine.

But in July 1941, he decides to return to Germany and tries to hide his Jewish origins. On his return, he is arrested immediately for what 'treasonable assistance in arms'. It does not help him that, when he joined the Foreign Legion, he had been assured that he would not be deployed against the German Reich.

The verdict in 1942 comes to the conclusion that he had served an enemy military force. Seven years in prison means: concentration camp. The SS special camp Hinzert is waiting for him for the time being.

Granichstaedten was not the only fugitive in Diepoldsau who gave in to pressure from the Swiss authorities and was pushed out to France.

Willi Huber as well crossed the border to Switzerland in Hohenems on August 17, 1938.

Most of the Jews seeking refuge here at this time came from rather poor backgrounds, their families having moved to Vienna from Eastern Europe between 1900 and 1920, fleeing poverty, war and persecution. Willi Huber had attended a mechanical engineering school in Vienna and worked as a lathe operator. He also ended up in the refugee camp in Diepoldsau and tried to find a way to travel on from there to another safe country. The Swiss authorities regularly remind him that he will only be tolerated for a limited period. In July 1939, he is moved from Diepoldsau to Degersheim, where numerous refugees are also housed. And in August he sets off for France. Initially there are no major obstacles on the way. But for many, this journey becomes a trap.

But Willi Huber is lucky. He joins the French army. And he is lucky once again, because when the army surrenders after a very short time in June 1940, he manages to escape to Marseille in the unoccupied zone of France. Luck stays with him as he finds the love of his life there: the Viennese Gusti Auerbach, who also fled to Brussels in August 1938 and finally to Marseille in May 1940. They get married and decide to escape to Switzerland once again, this time from the west.

In the Alps south of Lake Geneva, they succeed to cross the border, from Chamonix to Valais with their two-month-old baby on September 24, 1942. They survive the war in various refugee homes in Lausanne and Montreux. And in August 1945, they make their way back to France - and are initially stuck in the Charmilles refugee camp in Geneva. Their identity papers, which they had to return in the meantime, had apparently ended up with the wrong office.

But even this last Swiss chapter of the now family of four passes. They were finally able to settle in Lyon, France.[3]

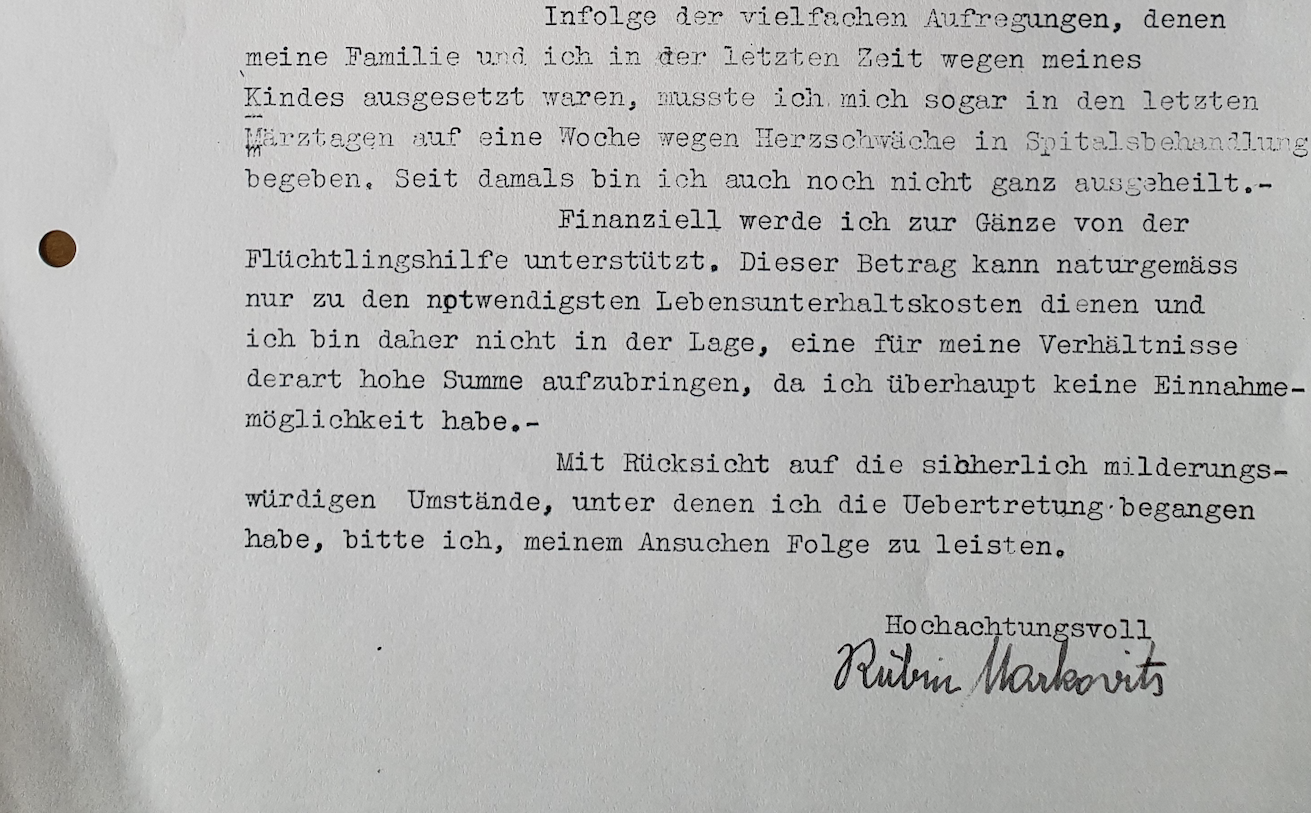

For other refugees from Diepoldsau, the route to France proved to be nothing more than a detour to their death sentence. Shoemaker Rubin Markowitz and his wife Jetti, for example, came from Eastern Europe, from Iași in Romania, like so many of the Viennese refugees. They too had arrived in Diepoldsau on August 16, 1938. After Kristallnacht, their son Heinrich was arrested in Vienna along with 6,500 other Jews and deported to Dachau on November 12. Released again - on condition that he leaves the Reich as quickly as possible - he also tries to escape to Switzerland via Vorarlberg. Rubin Markowitz hires escape helpers, the upholsterer Oskar Müller and the driving instructor Alexander Helg, who take Heinrich Markowitz from Altach across the Old Rhine. But the helpers get arrested on the Swiss side. All of them - including the desperate father - are sentenced to heavy fines. Rubin Markowitz, who has no means at all, applies to the district office for clemency.

“I openly declare that my conviction was justified and that I committed the offense, but I ask you to consider the situation in which I found myself when I heard that my underage child had to live in Germany without protection away from his parents and that I had no means of helping him at all. (...) I am supported financially in full by the refugee aid organization. Naturally, this amount can only be used for the most necessary living expenses and I am therefore not in a position to raise such a high amount considering my circumstances, as I have no means of income at all.”[4]

However, the request for clemency is not granted and he is now threatened with a prison sentence instead. On July 1, 1939, Rubin and Jetti leave for France together with their son Erich. It is not known whether they set off themselves or were deported by the authorities.

Two years later In any case, they were among the 4232 Jews arrested in France on August 20, 1941, in 'retaliation' for attacks by the Resistance on the German occupying forces. They were locked up in the Drancy transit camp near Paris. On July 19, 1942, they were forced to board the 7th transport to Auschwitz, together with 998 other Jewish men and women, crammed into freight cars. Two days later, after an odyssey via Châlons-sur-Marne, Saarbrücken, Frankfurt, Dresden and Katowice, the transport reached the Auschwitz extermination camp. The younger deportees, who were still classified as fit for work, were sent to the new Birkenau camp. The others were taken directly to the gas chamber and murdered. Only 16 people from this transport lived to see liberation in 1945.[5] No one from the Markowitz family was among them. Neither was Erich Markowitz, who was deported from Phitivier to Auschwitz on July 17 and murdered there in September. What became of Heinrich Markowitz is unknown.

And the story of the young runaway Felix Granichstaedten? It also ends in Auschwitz. It is not known when he was deported there from Hinzert or another camp. But the date of his death in Auschwitz is documented. He died on June 26, 1943 at the age of twenty-four, cause of death unknown.[6]

The conviction of Rubin Markowitz had a late repercussion in Switzerland. On November 30, 2005, the Rehabilitation Commission of the Federal Assembly declared that the conviction pronounced against Ruben Markowitz by the Unterrheintal District Office on May 25, 1939 had been annulled with effect from January 1, 2004 by the Federal Act of June 20, 2003 on the Annulment of Criminal Convictions against Refugee Helpers during the National Socialist Era. No procedural costs were charged.[7]

[1] Urteil gegen Felix Hans Granichstaedten, Volksgerichtshof Berlin, 10.3.1942, in: Datenbank Widerstand als „Hochverrat“. Die Anklage- und Urteilsschriften aus Verfahren im Deutschen Reich und Österreich;

[3] Dossier Dossier Wilhelm und Caecilie Huber, Bundesarchiv Bern: E4264#1988/2#8613* HUBER, WILHELM, 08.01.1920; HUBER, CAECILIE, 17.09.1897

[5] Markowitz Rubin, Opferdatenbank des Dokumentationsarchiv Österreichischer Widerstand (doew.at), siehe auch: https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/4961854 (13.1.2025)

[6] Zu Felix Granichstaedten und seiner Familie: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58126&tree=Hohenems

[7] Zu Rubin Markowitz und seiner Familie: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I59691&tree=Hohenems

17a Felix Granichstaedten, Wilhelm Huber, Rubin Markowitz.

Vienna, Diepoldsau, France and then?

Hohenems/Diepoldsau, August 17, 1938

In Bern, Heinrich Rothmund, head of the immigration police, summoned the cantonal police directors. On the same day, August 17, 1938, at least 37 refugees arrive in Diepoldsau from Vienna. In total, over 200 people fled to Switzerland via Hohenems and the old Rhine in that week alone. The main concern there is how to get rid of them again.

One of the refugees crossing the border that very day is Felix Hans Granichstaedten, the son of a well-known Viennese composer of operettas. The young man, a baptized Catholic like his father, had already experienced a few adventures. Born in Prague in 1919, he caused his parents quite a few headaches. In 1933, at the age of just fourteen, he ran away from home, hung around with some ruffians and was picked up a few days later in Pressbaum. The Viennese tabloids gleefully exploited the scandal. An apprenticeship as a mechanic was supposed to put him on the right track; then he worked in a department store, and attempted suicide.

In 1938, however, he had every reason to run away. The Granichstaedtens were now nothing but Jews in the eyes of the National Socialist authorities. In that same year his father, Bruno Granichstaedten, who had already spent some time in Hollywood in 1932, managed to escape – now married to his second wife – via Luxembourg to the US.

Felix Granichstaedten, however, found himself before the People's Court of the German Reich in Berlin on March 10, 1942. Charged with treason. How he got there from Diepoldsau is meticulously explained in the verdict for seven years in prison. It is a verdict that sounds almost sympathetic given the circumstances of National Socialism, but it will certainly not help him.

“After the annexation of the Ostmark to the Reich [...] the accused decided to emigrate because he did not want to remain in Germany as a Jew. On August 17, 1938, he traveled from Vienna to Vorarlberg and crossed the green border to Switzerland. Here he lived for about nine months in an emigrant camp in Diepoldsau. Then, as a Catholic, he was supported by the Caritas association and accommodated with a Catholic family near St. Gallen. From October 1939 he was taken in by the family of a lower post office official out of compassion, although there were already 9 children in the house. The accused, who did not have a work permit, tried to earn a small income by repairing radio sets. He was therefore summoned by the police, cautioned for working without a permit and referred to the Austrian and Foreign Legions in France.”[1]

But it was precisely this 'clue' that proved to be Granichstaedten's undoing. Apparently, even the judges who decide his fate still feel sorry for the young man. The story continues:

“The defendant, who had no prospect of getting a work permit and work in Switzerland, but who on the other hand no longer wanted to be a burden on the family that had taken him in, decided to go to France and join the Foreign Legion.”[2]

He was given a ticket by Swiss Caritas. Having crossed the borderin February 1940 he was awaited by the French Guard. He received his training in Sidi bel Abbès in Algeria. And after the capitulation of France in June, he finally enlisted in a work company in the fall, also in Algeria, becoming an electrician in the machine center of a coal mine.

But in July 1941, he decides to return to Germany and tries to hide his Jewish origins. On his return, he is arrested immediately for what 'treasonable assistance in arms'. It does not help him that, when he joined the Foreign Legion, he had been assured that he would not be deployed against the German Reich.

The verdict in 1942 comes to the conclusion that he had served an enemy military force. Seven years in prison means: concentration camp. The SS special camp Hinzert is waiting for him for the time being.

Granichstaedten was not the only fugitive in Diepoldsau who gave in to pressure from the Swiss authorities and was pushed out to France.

Willi Huber as well crossed the border to Switzerland in Hohenems on August 17, 1938.

Most of the Jews seeking refuge here at this time came from rather poor backgrounds, their families having moved to Vienna from Eastern Europe between 1900 and 1920, fleeing poverty, war and persecution. Willi Huber had attended a mechanical engineering school in Vienna and worked as a lathe operator. He also ended up in the refugee camp in Diepoldsau and tried to find a way to travel on from there to another safe country. The Swiss authorities regularly remind him that he will only be tolerated for a limited period. In July 1939, he is moved from Diepoldsau to Degersheim, where numerous refugees are also housed. And in August he sets off for France. Initially there are no major obstacles on the way. But for many, this journey becomes a trap.

But Willi Huber is lucky. He joins the French army. And he is lucky once again, because when the army surrenders after a very short time in June 1940, he manages to escape to Marseille in the unoccupied zone of France. Luck stays with him as he finds the love of his life there: the Viennese Gusti Auerbach, who also fled to Brussels in August 1938 and finally to Marseille in May 1940. They get married and decide to escape to Switzerland once again, this time from the west.

In the Alps south of Lake Geneva, they succeed to cross the border, from Chamonix to Valais with their two-month-old baby on September 24, 1942. They survive the war in various refugee homes in Lausanne and Montreux. And in August 1945, they make their way back to France - and are initially stuck in the Charmilles refugee camp in Geneva. Their identity papers, which they had to return in the meantime, had apparently ended up with the wrong office.

But even this last Swiss chapter of the now family of four passes. They were finally able to settle in Lyon, France.[3]

For other refugees from Diepoldsau, the route to France proved to be nothing more than a detour to their death sentence. Shoemaker Rubin Markowitz and his wife Jetti, for example, came from Eastern Europe, from Iași in Romania, like so many of the Viennese refugees. They too had arrived in Diepoldsau on August 16, 1938. After Kristallnacht, their son Heinrich was arrested in Vienna along with 6,500 other Jews and deported to Dachau on November 12. Released again - on condition that he leaves the Reich as quickly as possible - he also tries to escape to Switzerland via Vorarlberg. Rubin Markowitz hires escape helpers, the upholsterer Oskar Müller and the driving instructor Alexander Helg, who take Heinrich Markowitz from Altach across the Old Rhine. But the helpers get arrested on the Swiss side. All of them - including the desperate father - are sentenced to heavy fines. Rubin Markowitz, who has no means at all, applies to the district office for clemency.

“I openly declare that my conviction was justified and that I committed the offense, but I ask you to consider the situation in which I found myself when I heard that my underage child had to live in Germany without protection away from his parents and that I had no means of helping him at all. (...) I am supported financially in full by the refugee aid organization. Naturally, this amount can only be used for the most necessary living expenses and I am therefore not in a position to raise such a high amount considering my circumstances, as I have no means of income at all.”[4]

However, the request for clemency is not granted and he is now threatened with a prison sentence instead. On July 1, 1939, Rubin and Jetti leave for France together with their son Erich. It is not known whether they set off themselves or were deported by the authorities.

Two years later In any case, they were among the 4232 Jews arrested in France on August 20, 1941, in 'retaliation' for attacks by the Resistance on the German occupying forces. They were locked up in the Drancy transit camp near Paris. On July 19, 1942, they were forced to board the 7th transport to Auschwitz, together with 998 other Jewish men and women, crammed into freight cars. Two days later, after an odyssey via Châlons-sur-Marne, Saarbrücken, Frankfurt, Dresden and Katowice, the transport reached the Auschwitz extermination camp. The younger deportees, who were still classified as fit for work, were sent to the new Birkenau camp. The others were taken directly to the gas chamber and murdered. Only 16 people from this transport lived to see liberation in 1945.[5] No one from the Markowitz family was among them. Neither was Erich Markowitz, who was deported from Phitivier to Auschwitz on July 17 and murdered there in September. What became of Heinrich Markowitz is unknown.

And the story of the young runaway Felix Granichstaedten? It also ends in Auschwitz. It is not known when he was deported there from Hinzert or another camp. But the date of his death in Auschwitz is documented. He died on June 26, 1943 at the age of twenty-four, cause of death unknown.[6]

The conviction of Rubin Markowitz had a late repercussion in Switzerland. On November 30, 2005, the Rehabilitation Commission of the Federal Assembly declared that the conviction pronounced against Ruben Markowitz by the Unterrheintal District Office on May 25, 1939 had been annulled with effect from January 1, 2004 by the Federal Act of June 20, 2003 on the Annulment of Criminal Convictions against Refugee Helpers during the National Socialist Era. No procedural costs were charged.[7]

[1] Urteil gegen Felix Hans Granichstaedten, Volksgerichtshof Berlin, 10.3.1942, in: Datenbank Widerstand als „Hochverrat“. Die Anklage- und Urteilsschriften aus Verfahren im Deutschen Reich und Österreich;

[3] Dossier Dossier Wilhelm und Caecilie Huber, Bundesarchiv Bern: E4264#1988/2#8613* HUBER, WILHELM, 08.01.1920; HUBER, CAECILIE, 17.09.1897

[5] Markowitz Rubin, Opferdatenbank des Dokumentationsarchiv Österreichischer Widerstand (doew.at), siehe auch: https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/4961854 (13.1.2025)

[6] Zu Felix Granichstaedten und seiner Familie: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58126&tree=Hohenems

[7] Zu Rubin Markowitz und seiner Familie: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I59691&tree=Hohenems