Judith Kohn> End of August 1938

19a Judith Kohn

“What kind of human being am I?” Judith Kohn meets border police and helpers

Bregenz-Lustenau-Diepoldsau, end of August 1938

Like so many others, Judith Kohn sets off from Vienna. She says goodbye to her parents at Westbahnhof trainstation.

“These were awful scenes. The parents of so many young people, with or without passports or visas, who were trying to take their fate into their own hands, had to say goodbye. It was terrible, my parents came too. Unfortunately, my brother had been hospitalized and couldn't come.”[1]

Perhaps she already suspects that she will never see her parents again? Traveling with her is an acquaintance: Willi, the groom of the seamstress she has just spent time learning to sew with.

“We left there in the evening, sat like sardines in those uncomfortable wooden armchairs and kept waiting for a police raid to come. His name was Willi, the dressmaker's groom. He was very nice to me. Sometimes I was allowed to put my head on his shoulder so that I could get some sleep. And then we arrived in Innsbruck at sunrise. We got off the train there to buy tickets again and started talking to two guys from Burgenland who had the same destination as we did. At the last moment, distracted by this conversation, we got on a train and realized with horror that it was the wrong train, a train back to Vienna. We got off at the first station and walked back. And that was a coincidence that saved the life of Willi, who had no papers at all apart from a birth certificate, and me. Because later we found out that there was a raid on the right train, the one we should have boarded, and everyone who didn't have valid papers, like me and Willi for example, was arrested. And our fate would have been concentration camp.”

Judith Kohn grew up with her grandparents in Szentgottard in Hungary, the place where she was born in 1917. Her parents had to escape anti-Semitic violence to Vienna for the first time in 1919 after the defeat of the revolution.

In March 1938, when Judith was a young medical student in Vienna herself, she experienced the so-called Anschluss and the pogrom atmosphere of the first days in Austria, having to watch people being mistreated and her parents being traumatized for a second time.

What gives her support during this time is perhaps her love for the chemistry student Jefim Braude, the brother of her friend Dina.

But now both Judith and Jefim have to abandon their studies. They have to obtain valid passports and possibly a visa. Judith works as a nurse at the Rothschild Hospital in Vienna for a few months, attends classes in nursing and infant care, and learns to work as a seamstress. Practical professions increase the chances of obtaining a visa.

But the hope of a legal exit is not fulfilled. At the beginning of August, Jefim escapes to Switzerland via Basel with his sister and her boyfriend. Judith follows at the end of August together with Willi, who knows that his bride is already in Switzerland as well.

When they finally arrive in Bregenz, they don't know what to do next. At the train station, someone asks them if they are Jewish. And takes them to a place where two boys are already sleeping who have tried unsuccessfully to get into Switzerland several times. The border has been closed since August 17.

One of the boys gives up and goes back to Vienna, the other claims that he found out where to cross over.

“And - we decided to let this fellow lead us after all. We... we went to a branch of the Rhine in the dark and wanted to cross the embankment. But as soon as we got there, we were illuminated with headlights from the other side, from the Swiss side.

It was August, but it was terribly cold and we just waited until we had the feeling: now is the time, now the air might be clear. We took off our clothes, holding them over our heads, and more or less swam. The water was a bit deeper than we were tall, and then we got dressed again and wanted to cross the embankment.

At that moment, a Swiss border guard was already there. 'Stop or I'll shoot, put your hands up!’ Of course, I immediately put my hands up and see a border guard pointing his gun at me. …“

Judith realizes that she is now alone with the two young Burgenlanders she met on the train. The other two, Willi and the guy from the Bregenz accommodation, have managed to escape through the cornfield into Switzerland.

“This border guard ordered us to cross the Rhine back into Austria. That would have meant certain pneumonia, so we more or less refused.

But when he wouldn't let go, I opened the neckline of my dress and told him: 'Shoot!’ I was so desperate, so starved, that I had the feeling it would all be over in a second. He then lowered his rifle, mumbled something like: 'What kind of human being am I' and said he would lead us to the Austrian customs house. …

Then we stood there at night in Austria: 'Where should we sleep?' We found a stable. There were cows and horses there and it was warm and the boys were nice. They put their gloves, which my mother had knitted and given them at the end, on my feet and I was so happy I wasn't alone.

Then, of course, the next day we were very hungry and we satisfied our hunger with apples that were still unripe and had fallen from the trees; and then the two lads said they would buy me a coffee in a pub in Lustenau, right on the border.“

The 'Schweizerhaus' inn, just a few hundred meters from the border, is used to receiving refugees and provides help.

The landlady invites them to sleep unnoticed in the kitchen. It is probably the middle of the day, but the three are exhausted. A border policeman arrives, accepts the passports of the two boys and turns a blind eye when he is handed Judith's invalid passport.

“Soon I am awakened again. And now I look into the eyes of an old man, an ancient man. Later I learned that he was 53 years old. For me the Methuselah.

A worn-out face. A Swiss man who says to me: 'Miss, I heard your groom is in Switzerland and you can't go. My heart won't allow it. I may have had a drink, but what I tell you is what I mean. I'll just inform my wife. Because I can be arrested here and come back. Wait for me. I'm a good smuggler. I'll take you across.'”

But evening falls and no one shows up. In the meantime, Judith has also heard about the pipe that carries a canal across the Old Rhine nearby. But before the three of them can make their next attempt to escape there, the helper from across the border appears after all. He takes them on the path through the shallow arm of the Rhine, next to the Schmitter border crossing. Contrary to their expectations, no border guard appears.

“Then he says, 'Take off your shoes.' And then there was a stubble field. It scratched our feet, of course, but we didn't feel a thing. And he directed us like... at least an officer: 'Duck, run, stop, lie down, run again! All of a sudden I remember that we had to hide behind a really big tree, it was so wide that we, that he meant that if we were hiding behind it, we wouldn't be seen from the other side. Then we walked on and suddenly we were in a brightly lit kitchen in Switzerland, where a ... his wife was - friendly, she gave us food and drink.

And the Swiss man told his wife to make up his bed next to her for me, because he was going up to the attic with the boys, where his five children slept. The next day a woman came, poorly dressed, and brought us money from people there in Diepoldsau who had heard about our fate and collected money for us.”

Judith Kohn did not stay in Switzerland for long. That same day, she met Jefim Braude, her fiancé, in St. Gallen.

Together they manage to get to France via Geneva. They live in Paris for a short time, then in Montpellier, where they get married. And for a while they are even able to study. But they are still not safe. Once again, chance and luck have to come into play. An American, whom Judith's family had once helped as a child in Hungary, is prepared to sponsor an affidavit for her. And as her husband originally comes from Minsk, they are eligible for the Russian quota on which there are still places available. On September 1, the day the German invasion of Poland marks the beginning of World War II, they actually receive the necessary passports in Marseille. And a little later, the ship passages to the USA. They arrive in New York on October 18, 1939. But they do not feel comfortable there. Jefim dreams of returning to Austria.

Only after the war Judith finds out what has become of her parents and brother, whom she had desperately tried to help to emigrate to the US in 1940. They all ended up in Auschwitz, as did a large part of the rest of her family.

Nevertheless, Jefim Braude returns to Europe in 1945 as a translator for the US army. Judith Braude studies medicine in Paris for a year. In 1947, they settle back in Vienna. And experience a city in which they still encounter an openly anti-Semitic atmosphere.

“My husband loved this country almost religiously.” She recalls in the lengthy interview she gave to the Shoah Foundation in 1998. She herself returned out of love for him, eventually became a doctor, even though she probably never felt at home in the city again.

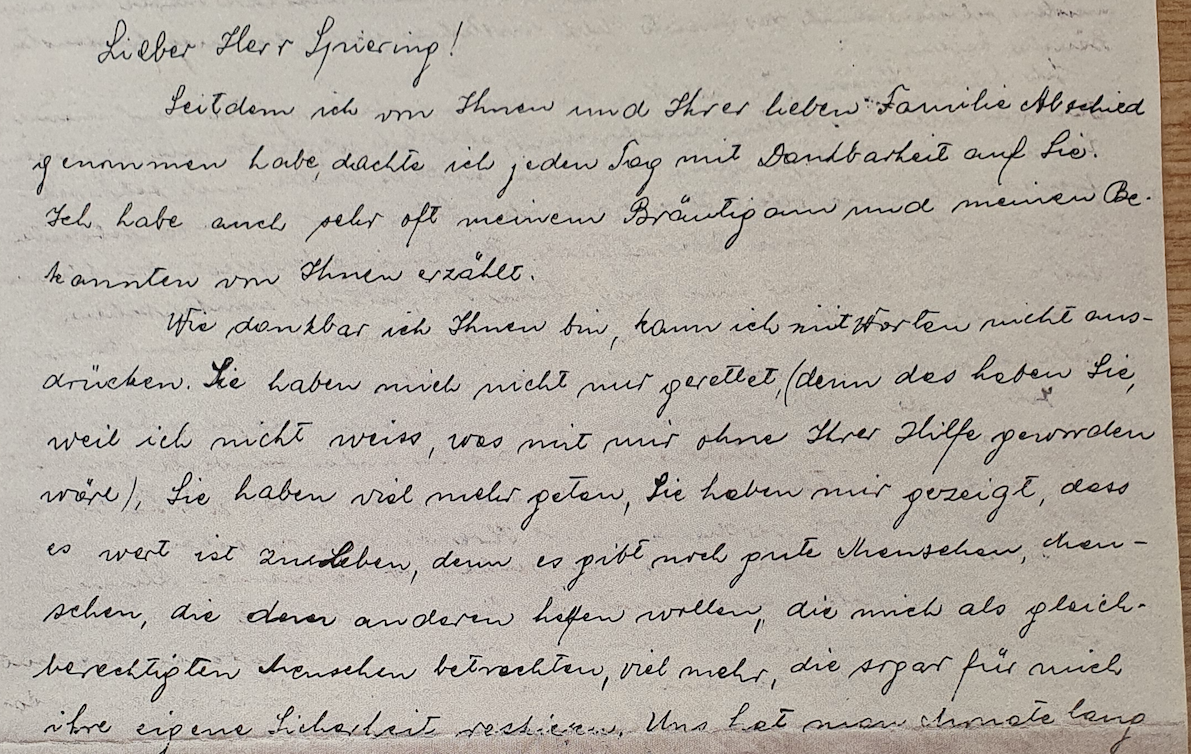

She never forgot the people who helped her along the way. As early as 1939, she wrote to her rescuer Johann Spirig from Paris:

“Since I said goodbye to you and your dear family, I have thought of you with gratitude every day. I have also told my groom and my friends about you very often. ... You didn't just save me (because you did, because I don't know what would have happened to me without your help), you did much more, you showed me that it is worth living, because there are still good people out there.”[2]

[2] Judith Braude to Johann Spirig, Paris 1939, copy in the JMH archive. More about Judith Kohn and her family: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I49029&tree=Hohenems

19a Judith Kohn

“What kind of human being am I?” Judith Kohn meets border police and helpers

Bregenz-Lustenau-Diepoldsau, end of August 1938

Like so many others, Judith Kohn sets off from Vienna. She says goodbye to her parents at Westbahnhof trainstation.

“These were awful scenes. The parents of so many young people, with or without passports or visas, who were trying to take their fate into their own hands, had to say goodbye. It was terrible, my parents came too. Unfortunately, my brother had been hospitalized and couldn't come.”[1]

Perhaps she already suspects that she will never see her parents again? Traveling with her is an acquaintance: Willi, the groom of the seamstress she has just spent time learning to sew with.

“We left there in the evening, sat like sardines in those uncomfortable wooden armchairs and kept waiting for a police raid to come. His name was Willi, the dressmaker's groom. He was very nice to me. Sometimes I was allowed to put my head on his shoulder so that I could get some sleep. And then we arrived in Innsbruck at sunrise. We got off the train there to buy tickets again and started talking to two guys from Burgenland who had the same destination as we did. At the last moment, distracted by this conversation, we got on a train and realized with horror that it was the wrong train, a train back to Vienna. We got off at the first station and walked back. And that was a coincidence that saved the life of Willi, who had no papers at all apart from a birth certificate, and me. Because later we found out that there was a raid on the right train, the one we should have boarded, and everyone who didn't have valid papers, like me and Willi for example, was arrested. And our fate would have been concentration camp.”

Judith Kohn grew up with her grandparents in Szentgottard in Hungary, the place where she was born in 1917. Her parents had to escape anti-Semitic violence to Vienna for the first time in 1919 after the defeat of the revolution.

In March 1938, when Judith was a young medical student in Vienna herself, she experienced the so-called Anschluss and the pogrom atmosphere of the first days in Austria, having to watch people being mistreated and her parents being traumatized for a second time.

What gives her support during this time is perhaps her love for the chemistry student Jefim Braude, the brother of her friend Dina.

But now both Judith and Jefim have to abandon their studies. They have to obtain valid passports and possibly a visa. Judith works as a nurse at the Rothschild Hospital in Vienna for a few months, attends classes in nursing and infant care, and learns to work as a seamstress. Practical professions increase the chances of obtaining a visa.

But the hope of a legal exit is not fulfilled. At the beginning of August, Jefim escapes to Switzerland via Basel with his sister and her boyfriend. Judith follows at the end of August together with Willi, who knows that his bride is already in Switzerland as well.

When they finally arrive in Bregenz, they don't know what to do next. At the train station, someone asks them if they are Jewish. And takes them to a place where two boys are already sleeping who have tried unsuccessfully to get into Switzerland several times. The border has been closed since August 17.

One of the boys gives up and goes back to Vienna, the other claims that he found out where to cross over.

“And - we decided to let this fellow lead us after all. We... we went to a branch of the Rhine in the dark and wanted to cross the embankment. But as soon as we got there, we were illuminated with headlights from the other side, from the Swiss side.

It was August, but it was terribly cold and we just waited until we had the feeling: now is the time, now the air might be clear. We took off our clothes, holding them over our heads, and more or less swam. The water was a bit deeper than we were tall, and then we got dressed again and wanted to cross the embankment.

At that moment, a Swiss border guard was already there. 'Stop or I'll shoot, put your hands up!’ Of course, I immediately put my hands up and see a border guard pointing his gun at me. …“

Judith realizes that she is now alone with the two young Burgenlanders she met on the train. The other two, Willi and the guy from the Bregenz accommodation, have managed to escape through the cornfield into Switzerland.

“This border guard ordered us to cross the Rhine back into Austria. That would have meant certain pneumonia, so we more or less refused.

But when he wouldn't let go, I opened the neckline of my dress and told him: 'Shoot!’ I was so desperate, so starved, that I had the feeling it would all be over in a second. He then lowered his rifle, mumbled something like: 'What kind of human being am I' and said he would lead us to the Austrian customs house. …

Then we stood there at night in Austria: 'Where should we sleep?' We found a stable. There were cows and horses there and it was warm and the boys were nice. They put their gloves, which my mother had knitted and given them at the end, on my feet and I was so happy I wasn't alone.

Then, of course, the next day we were very hungry and we satisfied our hunger with apples that were still unripe and had fallen from the trees; and then the two lads said they would buy me a coffee in a pub in Lustenau, right on the border.“

The 'Schweizerhaus' inn, just a few hundred meters from the border, is used to receiving refugees and provides help.

The landlady invites them to sleep unnoticed in the kitchen. It is probably the middle of the day, but the three are exhausted. A border policeman arrives, accepts the passports of the two boys and turns a blind eye when he is handed Judith's invalid passport.

“Soon I am awakened again. And now I look into the eyes of an old man, an ancient man. Later I learned that he was 53 years old. For me the Methuselah.

A worn-out face. A Swiss man who says to me: 'Miss, I heard your groom is in Switzerland and you can't go. My heart won't allow it. I may have had a drink, but what I tell you is what I mean. I'll just inform my wife. Because I can be arrested here and come back. Wait for me. I'm a good smuggler. I'll take you across.'”

But evening falls and no one shows up. In the meantime, Judith has also heard about the pipe that carries a canal across the Old Rhine nearby. But before the three of them can make their next attempt to escape there, the helper from across the border appears after all. He takes them on the path through the shallow arm of the Rhine, next to the Schmitter border crossing. Contrary to their expectations, no border guard appears.

“Then he says, 'Take off your shoes.' And then there was a stubble field. It scratched our feet, of course, but we didn't feel a thing. And he directed us like... at least an officer: 'Duck, run, stop, lie down, run again! All of a sudden I remember that we had to hide behind a really big tree, it was so wide that we, that he meant that if we were hiding behind it, we wouldn't be seen from the other side. Then we walked on and suddenly we were in a brightly lit kitchen in Switzerland, where a ... his wife was - friendly, she gave us food and drink.

And the Swiss man told his wife to make up his bed next to her for me, because he was going up to the attic with the boys, where his five children slept. The next day a woman came, poorly dressed, and brought us money from people there in Diepoldsau who had heard about our fate and collected money for us.”

Judith Kohn did not stay in Switzerland for long. That same day, she met Jefim Braude, her fiancé, in St. Gallen.

Together they manage to get to France via Geneva. They live in Paris for a short time, then in Montpellier, where they get married. And for a while they are even able to study. But they are still not safe. Once again, chance and luck have to come into play. An American, whom Judith's family had once helped as a child in Hungary, is prepared to sponsor an affidavit for her. And as her husband originally comes from Minsk, they are eligible for the Russian quota on which there are still places available. On September 1, the day the German invasion of Poland marks the beginning of World War II, they actually receive the necessary passports in Marseille. And a little later, the ship passages to the USA. They arrive in New York on October 18, 1939. But they do not feel comfortable there. Jefim dreams of returning to Austria.

Only after the war Judith finds out what has become of her parents and brother, whom she had desperately tried to help to emigrate to the US in 1940. They all ended up in Auschwitz, as did a large part of the rest of her family.

Nevertheless, Jefim Braude returns to Europe in 1945 as a translator for the US army. Judith Braude studies medicine in Paris for a year. In 1947, they settle back in Vienna. And experience a city in which they still encounter an openly anti-Semitic atmosphere.

“My husband loved this country almost religiously.” She recalls in the lengthy interview she gave to the Shoah Foundation in 1998. She herself returned out of love for him, eventually became a doctor, even though she probably never felt at home in the city again.

She never forgot the people who helped her along the way. As early as 1939, she wrote to her rescuer Johann Spirig from Paris:

“Since I said goodbye to you and your dear family, I have thought of you with gratitude every day. I have also told my groom and my friends about you very often. ... You didn't just save me (because you did, because I don't know what would have happened to me without your help), you did much more, you showed me that it is worth living, because there are still good people out there.”[2]

[2] Judith Braude to Johann Spirig, Paris 1939, copy in the JMH archive. More about Judith Kohn and her family: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I49029&tree=Hohenems