Edith Arm> December 29, 1938

20a Edith Arm

“There can't be no God...” Edith Arm’s journey into the Caribbean

Vienna – Diepoldsau – Santo Domingo, December 29, 1938

“My father was picked up by the Gestapo during the Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. I screamed with terror: The leather coats of the men frightened me. He was taken to a gym hall, along with others, and there they were beaten half-dead. But one of the guards knew him and let him jump out of a toilet window. He came home and immediately departed with a suitcase. After that shock I said to myself. There can be no God. A few days later, together with his brother, he escaped to Switzerland, crossing the frontier near Hohenems. My mother and I had a letter from him that ‘a girl with yellow hair’ in Hohenems would tell us everything else. We actually found her and she explained everything to us. We went to the German customs office and they examined us incredibly thoroughly because they probably thought we wanted to smuggle gold or whatever out of the country. They examined every opening of our bodies, my mother’s and mine, and for that we had to strip naked. They didn’t remark on the fact that we were wearing two or three layers of clothes; they knew we were leaving the country and this was nothing special. (…) Then we were told: ‘We’re letting you go, but don’t ever come back. If you come back, that’ll be the end of you’ – these were their exact words. And on the Swiss side father was waiting for us.”[1]

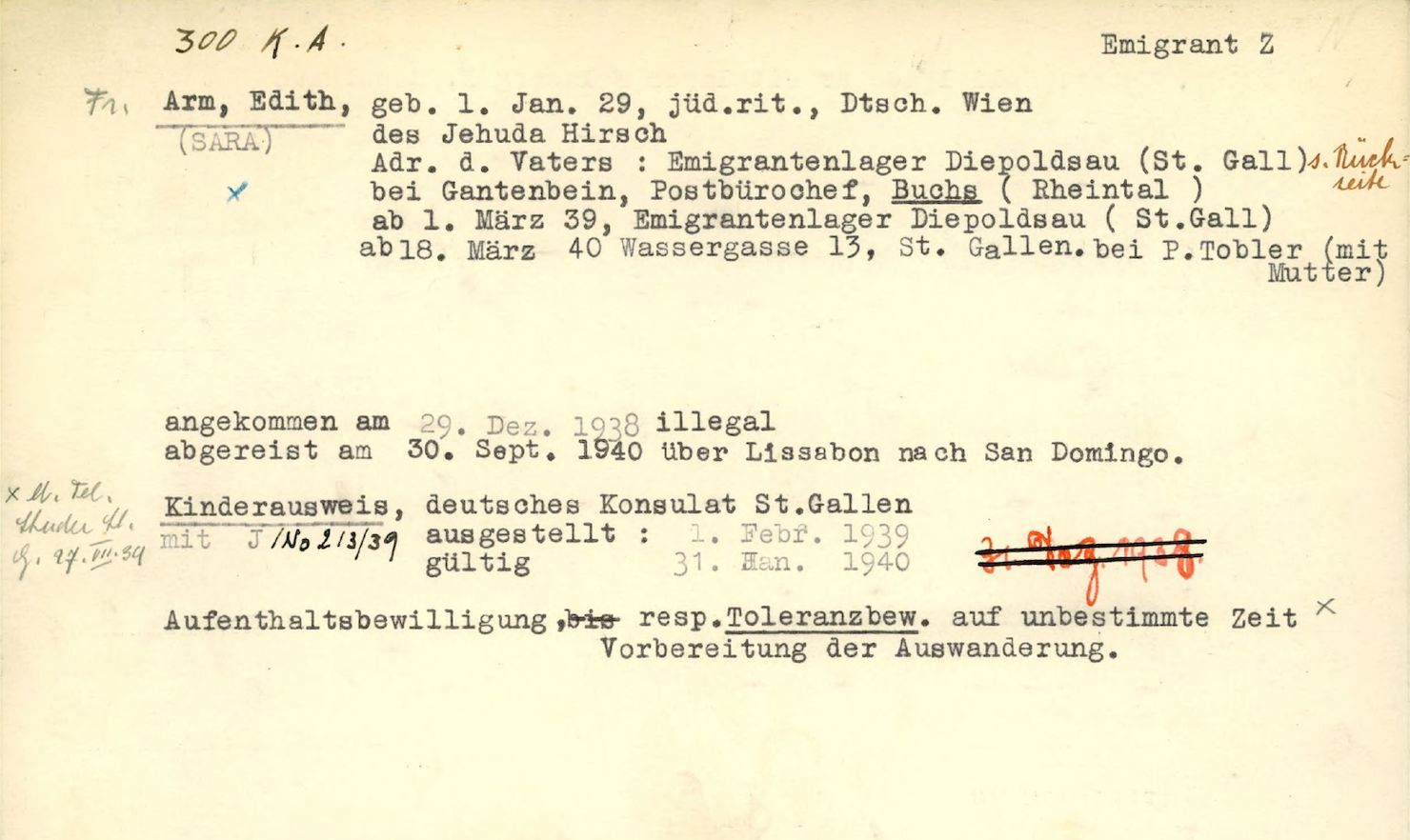

Her father Josef Arm and uncle Fritz fled to Diepoldsau on November 27, 1938. It is not known where they managed to cross the border. From the refugee camp, however, they were able to prepare the escape of Edith and her mother Elsa. On December 29, three days before Edith's tenth birthday, they also arrive at the Diepoldsau refugee camp.

“There we were for 15 months; it was cold and there wasn’t always enough food. Not that we went hungry. Even if it was only potatoes and cheese, there was always something to eat. It was not a pleasant place to be, and to me it was rather terrible. But the worst had nothing to do with food or cold.”

Soon after their arrival, the authorities decide to separate Edith from her family and place her with Swiss foster parents. The family of a postmaster in Buchs is supposed to look after her. But Edith runs away to be with her own parents, only to be sent back to Buchs again. Her parents have to fight for her. Eventually they are all reunited in Diepoldsau.

“Of course, while I was at Diepoldsau I missed my schooling. I had to be taught somehow. I knew the whole of Goethe’s Faust by heart. We staged a play: we sang songs. I received instruction in all possible and impossible subjects. There was no schoolmaster among us, but they all became teachers. (…) Then there was a composer. Somewhere an old piano was discovered and they made up a song for me.”

A soccer team is also formed. Fritz and Josef Arm are passionate kickers.

“After a year or so someone came from America, a certain Mr. Throne. He represented an organization called the Dominican Republic Settlement Association, DORSA in short. They collected money in the States and had arranged with the Dominican Republic that the country would allow Jewish refugees in. The figure envisioned was 100.000 – but this was never achieved. We were at most 450 people. Why? The Dominican president then had a very bad reputation, allegedly rightly so. So someone suggested to him that it would help his image if he authorized such a humanitarian project. Besides, this didn’t cost him anything; it was land that had belonged to the United Fruit Company, which he’d thrown out of the country, and it was lying fallow. It was hoped that Europeans would bring culture and know-how with them, and that this wouldn’t be a bad thing.”

In fact, dictator Trujillo had reason to be concerned about his reputation. Having come to power in a coup in 1930 with US help, he was obsessed with the idea of whitening his population. He himself, of Haitian descent, tried to do so with powder and white make-up and splendid uniforms. In 1937, he had at least 18,000 Haitians killed in a massacre, mainly workers on the sugar cane plantations.

When in July 1938, at the Evian Conference on Lake Geneva, an effort was made to find host countries for the threatened Jews from the German Reich, he offered to take in 100,000 of them. But in fact, only a few hundred came to the country and founded a Jewish colony near the city of Sosúa on the land made available to them.

Edith and her parents Josef and Elsa also set off for the Dominican Republic at the end of September 1940 with a whole group of refugees from the Diepoldsau camp. On December 3, they reach “Ciudad Trujillo”, as the capital Santo Domingo was called at the time, on the steamer S.S. Coamo from Puerto Rico - and shortly afterwards Sosúa, where Edith's uncle Fritz soon arrives too. Edith's aunts managed to flee to England, her uncle Sucher, known as Putzi, to Palestine. Like so many of those who fled from Vienna to Switzerland, their family came from Eastern Europe, impoverished people who had landed in Vienna's Leopoldstadt district around the time of the First World War. In 1938, they had long since formed the majority of Viennese Jewry. Small traders and workers, tailors and upholsterers, butchers and taxi drivers, like Josef Arm. People with no chance of obtaining an expensive visa to the USA.

In 1942, Edith's grandmother Netty, born in Novoselitsa near Chernivtsi, widowed for ten years and now all alone, was taken from her apartment in Vienna's Herminengasse and deported to Izbica in Poland. Whether she reached this place of extermination or died on the transport is unknown.

In any case, she never met her grandchildren, who were born in the Caribbean.[2]

[1] Edith Gersten née Arm recollections in: Adi Wimmer (Ed.), Strangers at Home and Abroad: Recollections of Austrian Jews Who Escaped Hitler. Jefferson, NC, 2000, p. 82ff.

[2] More on Edith Arm and her family: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I49029&tree=Hohenems

20a Edith Arm

“There can't be no God...” Edith Arm’s journey into the Caribbean

Vienna – Diepoldsau – Santo Domingo, December 29, 1938

“My father was picked up by the Gestapo during the Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. I screamed with terror: The leather coats of the men frightened me. He was taken to a gym hall, along with others, and there they were beaten half-dead. But one of the guards knew him and let him jump out of a toilet window. He came home and immediately departed with a suitcase. After that shock I said to myself. There can be no God. A few days later, together with his brother, he escaped to Switzerland, crossing the frontier near Hohenems. My mother and I had a letter from him that ‘a girl with yellow hair’ in Hohenems would tell us everything else. We actually found her and she explained everything to us. We went to the German customs office and they examined us incredibly thoroughly because they probably thought we wanted to smuggle gold or whatever out of the country. They examined every opening of our bodies, my mother’s and mine, and for that we had to strip naked. They didn’t remark on the fact that we were wearing two or three layers of clothes; they knew we were leaving the country and this was nothing special. (…) Then we were told: ‘We’re letting you go, but don’t ever come back. If you come back, that’ll be the end of you’ – these were their exact words. And on the Swiss side father was waiting for us.”[1]

Her father Josef Arm and uncle Fritz fled to Diepoldsau on November 27, 1938. It is not known where they managed to cross the border. From the refugee camp, however, they were able to prepare the escape of Edith and her mother Elsa. On December 29, three days before Edith's tenth birthday, they also arrive at the Diepoldsau refugee camp.

“There we were for 15 months; it was cold and there wasn’t always enough food. Not that we went hungry. Even if it was only potatoes and cheese, there was always something to eat. It was not a pleasant place to be, and to me it was rather terrible. But the worst had nothing to do with food or cold.”

Soon after their arrival, the authorities decide to separate Edith from her family and place her with Swiss foster parents. The family of a postmaster in Buchs is supposed to look after her. But Edith runs away to be with her own parents, only to be sent back to Buchs again. Her parents have to fight for her. Eventually they are all reunited in Diepoldsau.

“Of course, while I was at Diepoldsau I missed my schooling. I had to be taught somehow. I knew the whole of Goethe’s Faust by heart. We staged a play: we sang songs. I received instruction in all possible and impossible subjects. There was no schoolmaster among us, but they all became teachers. (…) Then there was a composer. Somewhere an old piano was discovered and they made up a song for me.”

A soccer team is also formed. Fritz and Josef Arm are passionate kickers.

“After a year or so someone came from America, a certain Mr. Throne. He represented an organization called the Dominican Republic Settlement Association, DORSA in short. They collected money in the States and had arranged with the Dominican Republic that the country would allow Jewish refugees in. The figure envisioned was 100.000 – but this was never achieved. We were at most 450 people. Why? The Dominican president then had a very bad reputation, allegedly rightly so. So someone suggested to him that it would help his image if he authorized such a humanitarian project. Besides, this didn’t cost him anything; it was land that had belonged to the United Fruit Company, which he’d thrown out of the country, and it was lying fallow. It was hoped that Europeans would bring culture and know-how with them, and that this wouldn’t be a bad thing.”

In fact, dictator Trujillo had reason to be concerned about his reputation. Having come to power in a coup in 1930 with US help, he was obsessed with the idea of whitening his population. He himself, of Haitian descent, tried to do so with powder and white make-up and splendid uniforms. In 1937, he had at least 18,000 Haitians killed in a massacre, mainly workers on the sugar cane plantations.

When in July 1938, at the Evian Conference on Lake Geneva, an effort was made to find host countries for the threatened Jews from the German Reich, he offered to take in 100,000 of them. But in fact, only a few hundred came to the country and founded a Jewish colony near the city of Sosúa on the land made available to them.

Edith and her parents Josef and Elsa also set off for the Dominican Republic at the end of September 1940 with a whole group of refugees from the Diepoldsau camp. On December 3, they reach “Ciudad Trujillo”, as the capital Santo Domingo was called at the time, on the steamer S.S. Coamo from Puerto Rico - and shortly afterwards Sosúa, where Edith's uncle Fritz soon arrives too. Edith's aunts managed to flee to England, her uncle Sucher, known as Putzi, to Palestine. Like so many of those who fled from Vienna to Switzerland, their family came from Eastern Europe, impoverished people who had landed in Vienna's Leopoldstadt district around the time of the First World War. In 1938, they had long since formed the majority of Viennese Jewry. Small traders and workers, tailors and upholsterers, butchers and taxi drivers, like Josef Arm. People with no chance of obtaining an expensive visa to the USA.

In 1942, Edith's grandmother Netty, born in Novoselitsa near Chernivtsi, widowed for ten years and now all alone, was taken from her apartment in Vienna's Herminengasse and deported to Izbica in Poland. Whether she reached this place of extermination or died on the transport is unknown.

In any case, she never met her grandchildren, who were born in the Caribbean.[2]

[1] Edith Gersten née Arm recollections in: Adi Wimmer (Ed.), Strangers at Home and Abroad: Recollections of Austrian Jews Who Escaped Hitler. Jefferson, NC, 2000, p. 82ff.

[2] More on Edith Arm and her family: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I49029&tree=Hohenems