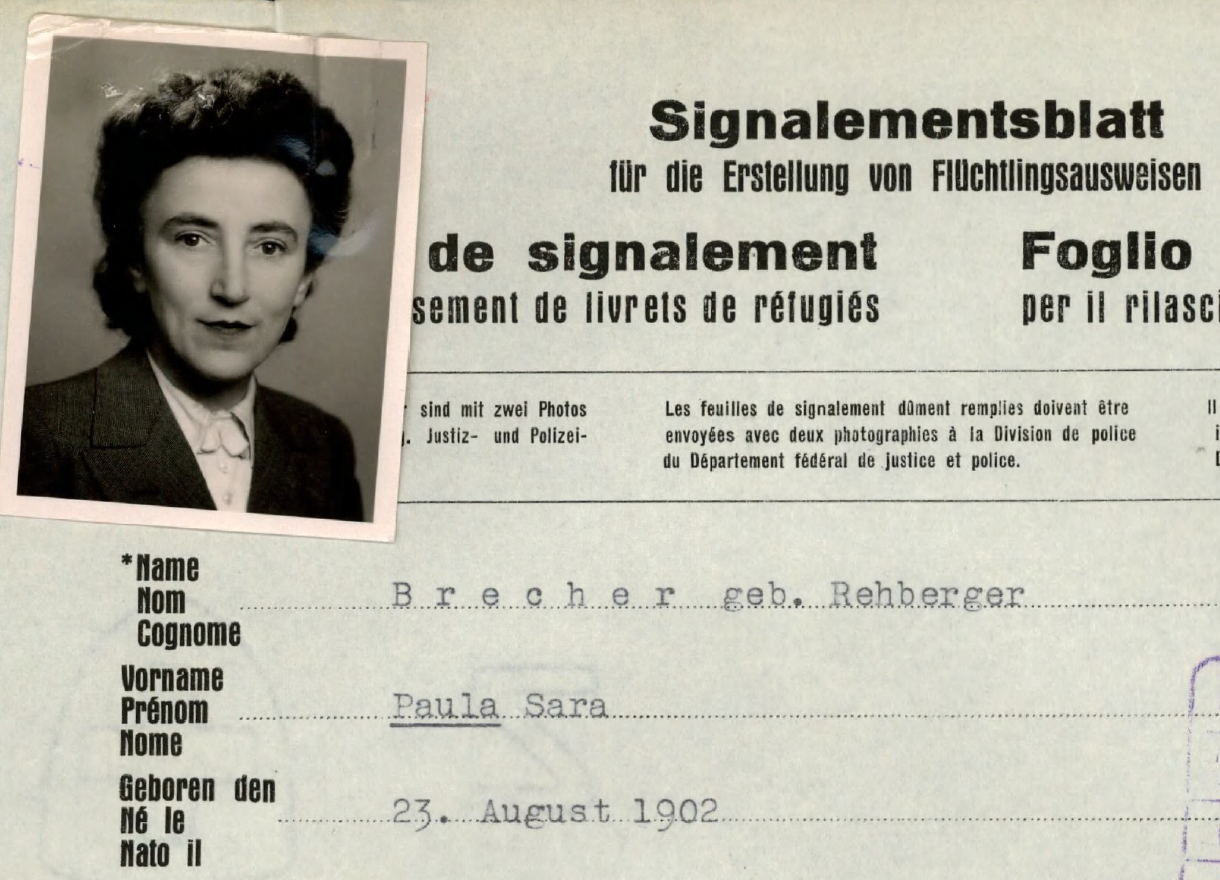

Paula Brecher> May 31, 1942

21a Paula Brecher

“The problem of fear”. Paula Brecher crosses the barbed wire

Hohenems/Diepoldsau, May 31, 1942

At 4.30 in the morning, the police station in Diepoldsau is informed by the border guards at the Schmitter crossing “that a woman coming from Germany has just crossed the border illegally”. Police officer Schneider is sent to the border to take the woman to the police station and interrogate her.

His report to the cantonal police is recorded as follows:

“Why did you escape to Switzerland?

On Monday, the 18th (of this month), 1 SS leader and two Jewish officials came to our apartment on Postgasse in Vienna and wanted to take all Jewish people under the age of 65 to a collection camp for deportation. As I suspected that this deportation would mean my death, or at least the most terrible torment, I fled from the apartment and hid with Aryan friends in Vienna. There I prepared my long-planned escape to Switzerland.”[1]

Paula Brecher believes that her parents are still safe from deportation due to their advanced age. Born as Paula Rehberger in 1902, she had already suffered several strokes of fate. During World War I, when her father was serving as a soldier, she had to drop out of school to help support the family. She does office work. But she also takes acting lessons. In 1920, she makes her debut at the Klagenfurt Theater and attracts attention with her own recital evening programs.

In 1922 she marries, but soon afterwards her husband falls ill and a radical change of climate is advised. In 1926, they set off for Algeria. But only three months later her husband dies and Paula Brecher returnes to Vienna as a widow. She keeps her head above water with recital evenings and a small widow's pension, writes prose and tries unsuccessfully to make a new start in Berlin. In 1933, she returns to Vienna to complete her A-levels and begins to study psychology.

In October 1938, she is the last Jewish woman to receive her doctorate in Vienna, with a thesis on “A psychological investigation into the problem of fear”. At the same time, she is banned from her profession. Her attempts to emigrate to the US prove unsuccessful, even though she receives an affidavit from a colleague in San Francisco. But by the time the visa is finally granted, it is already too late to travel through Italy. She needs financial support from her husband's aunt, who lives in Zurich, to make the journey via Japan. But when the money eventually arrives from Switzerland, the visa has expired. So she stays with her parents and witnesses the first deportations from Vienna, which now take place in quick succession, to Opole and Lodz, Kovno, Riga, Izbica, Minsk and There-sienstadt. Some of their relatives now also vanish without a trace.

The transport for which she is to be picked up on May 18, 1942 will depart two days later for Maly Trostinec near Minsk. Almost all of its passengers were no longer alive a few days later.

But Paula Brecher is on her way to Bregenz instead.

She describes her escape at the Diepoldsau police station on May 31:

“How did you organize this escape?

On my honeymoon in 1922, I was in Bregenz, where I was told, as a curiosity, that a lot of smuggling took place from there and that there was also an exchange of female workers between Switzerland and what was then Austria. I hoped that one of these opportunities would save me. (...) On Wednesday the 27th (of this month) I went to Bregenz where I visited a brother of a friend of my deceased husband. He dashed my hopes of crossing the border in Bregenz or Lustenau. The only possibility he saw was Hohenems, if I could find a guide there.”[2]

Paula Brecher goes to Hohenems to see Dr. Neudörfer, the head physician at the hospital, who has repeatedly helped refugees – even though he himself is at risk due to his Jewish ancestry. But in Hohenems she is passed around like a hot potato. Just three weeks ago, five women from Berlin failed in their attempt to escape at the border. One of them took her own life in Hohenems and died in Neudörfer's clinic. The Hohenems escape helpers were interrogated, the Diepoldsau escape helpers arrested in Switzerland. No one wants to accompany Paula Brecher to the border, only good advice is given as to which route she should take.

She does not find the recommended route. But in the middle of the night, at 2.30 a.m., she manages to get past the barbed wire fence in front of the Diepoldsau swimming pool. She sneaks along the wire fence of the swimming pool, crosses a shallow body of water north of the pool and is soon stopped by a Swiss border guard.

She has made it to Switzerland. However, her ordeal is not over yet. She is initially held in the St. Gallen police prison, until June 19th. She is then transferred to a Jewish girls' home in Basel, which now serves as refugee accommodation.

Just one day later, her parents are forced to leave Vienna. They are deported to Theresienstadt on June 20 on “Transport IV/1”. Moritz Rehberger, who was 44 years old when he went to fight for Austria in the First World War, perished in Theresienstadt on April 6, 1943. Paula's mother, Rosalie Rehberger survived in Theresienstadt until May 15, 1944. Then, at the age of 72, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered in the gas chambers. Paula Brecher would only learn of all this, years later.

However, she too is now physically and mentally ailing. In July 1942, she is hospitalized with a recurrence of a stomach ulcer. Soon afterwards, her Zurich benefactor dies and with her any hope for an easier right to stay. Paula Brecher now depends on the support of the Jewish Refugee Aid organizations She is finally allowed to move into private accommodation in 1943. She makes contact with the Basel circle around the psychoanalyist Heinrich Meng, who treats her as a therapist. Meng also tries to get her translation jobs, that are not subject to the strict ban on work that she is otherwise obliged to observe.

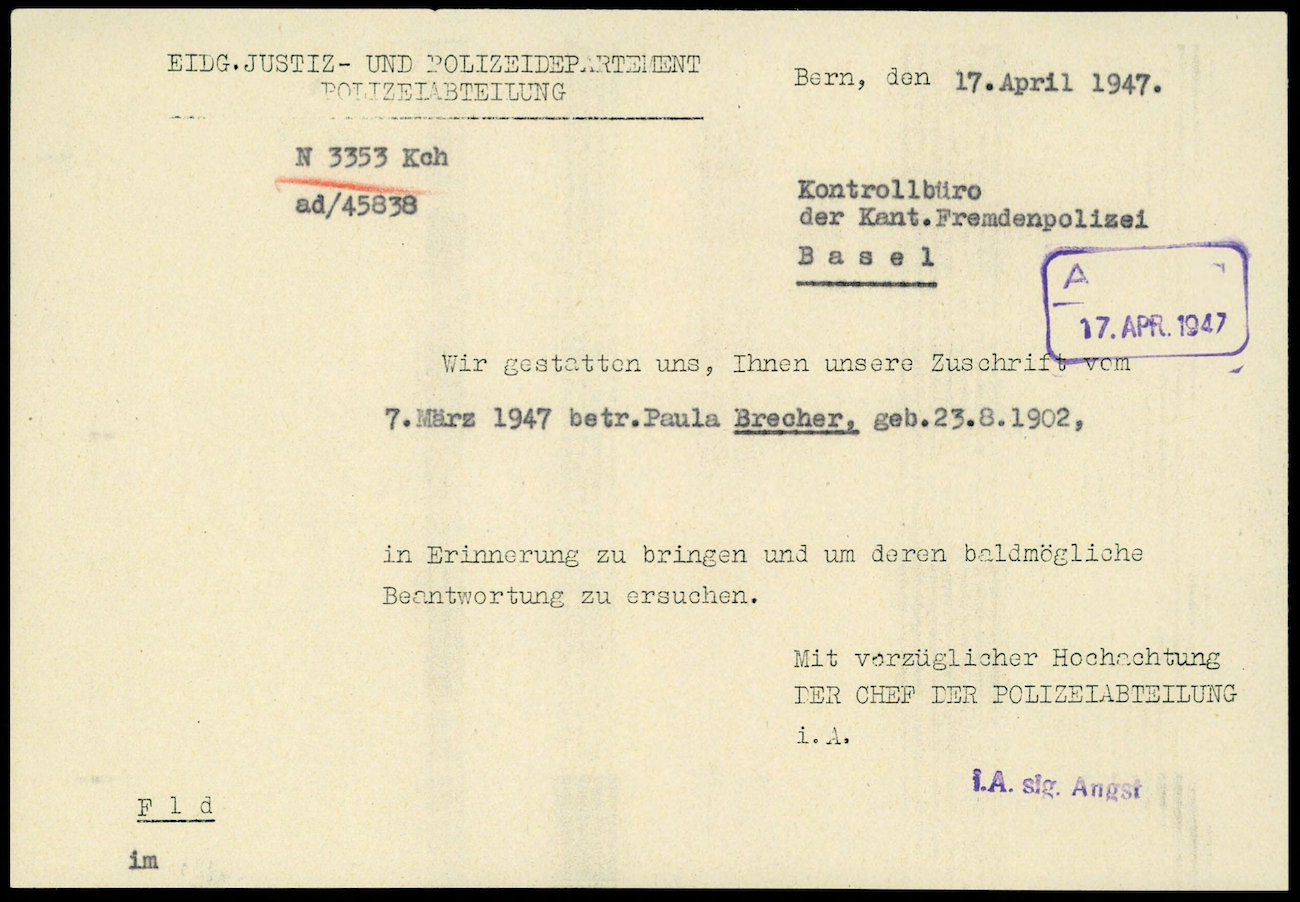

Hundreds of pages of correspondence from the immigration police in Bern, the Jewish Refugee Aid and the cantonal authorities document her struggle for survival in the following years, begging letters for medically necessary treatment and to obtain residence and work permits, and finally to secure permanent asylum. She still regularly receives official demands to apply for a visa for further emigration. She is still only occasionally allowed to do small paid jobs, a few language lessons here, a few translation jobs there. In 1949, the canton of Basel still refuses to grant her permanent asylum due to her poor health and states of anxiety. Paula Brecher has to fill in the International Refugee Organization's questionnaire twice more, explaining why she neither wants to return to Austria nor is able to emigrate to the USA.

Even the federal immigration police in Bern are now more friendly than the cantonal police. The letters from Bern are usually signed with a rubber-stamped name, on behalf of the authority, the “Chief of the Police Department”. Since 1948, the stamped letters from Bern bear the evocative name “Angst”.

It is “Fräulein Dr. Angst” who has since taken over the Brecher file. With her support, the time had actually come in February 1950. Paula Brecher receives the redemptive decision to be allowed to stay.

1974 she dies in Basel and is buried in the Jewish cemetery.[3]

[1] Diepoldsau police station, report on illegal entry into Switzerland, interrogation transcript, May 31, 1942; Swiss Federal Archives, Bern, Dossier Paula Brecher (E4264#1985/196#3189*)

[3] For Paula Brecher's (née Rehberger) biography, see: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58484&tree=Hohenems

21a Paula Brecher

“The problem of fear”. Paula Brecher crosses the barbed wire

Hohenems/Diepoldsau, May 31, 1942

At 4.30 in the morning, the police station in Diepoldsau is informed by the border guards at the Schmitter crossing “that a woman coming from Germany has just crossed the border illegally”. Police officer Schneider is sent to the border to take the woman to the police station and interrogate her.

His report to the cantonal police is recorded as follows:

“Why did you escape to Switzerland?

On Monday, the 18th (of this month), 1 SS leader and two Jewish officials came to our apartment on Postgasse in Vienna and wanted to take all Jewish people under the age of 65 to a collection camp for deportation. As I suspected that this deportation would mean my death, or at least the most terrible torment, I fled from the apartment and hid with Aryan friends in Vienna. There I prepared my long-planned escape to Switzerland.”[1]

Paula Brecher believes that her parents are still safe from deportation due to their advanced age. Born as Paula Rehberger in 1902, she had already suffered several strokes of fate. During World War I, when her father was serving as a soldier, she had to drop out of school to help support the family. She does office work. But she also takes acting lessons. In 1920, she makes her debut at the Klagenfurt Theater and attracts attention with her own recital evening programs.

In 1922 she marries, but soon afterwards her husband falls ill and a radical change of climate is advised. In 1926, they set off for Algeria. But only three months later her husband dies and Paula Brecher returnes to Vienna as a widow. She keeps her head above water with recital evenings and a small widow's pension, writes prose and tries unsuccessfully to make a new start in Berlin. In 1933, she returns to Vienna to complete her A-levels and begins to study psychology.

In October 1938, she is the last Jewish woman to receive her doctorate in Vienna, with a thesis on “A psychological investigation into the problem of fear”. At the same time, she is banned from her profession. Her attempts to emigrate to the US prove unsuccessful, even though she receives an affidavit from a colleague in San Francisco. But by the time the visa is finally granted, it is already too late to travel through Italy. She needs financial support from her husband's aunt, who lives in Zurich, to make the journey via Japan. But when the money eventually arrives from Switzerland, the visa has expired. So she stays with her parents and witnesses the first deportations from Vienna, which now take place in quick succession, to Opole and Lodz, Kovno, Riga, Izbica, Minsk and There-sienstadt. Some of their relatives now also vanish without a trace.

The transport for which she is to be picked up on May 18, 1942 will depart two days later for Maly Trostinec near Minsk. Almost all of its passengers were no longer alive a few days later.

But Paula Brecher is on her way to Bregenz instead.

She describes her escape at the Diepoldsau police station on May 31:

“How did you organize this escape?

On my honeymoon in 1922, I was in Bregenz, where I was told, as a curiosity, that a lot of smuggling took place from there and that there was also an exchange of female workers between Switzerland and what was then Austria. I hoped that one of these opportunities would save me. (...) On Wednesday the 27th (of this month) I went to Bregenz where I visited a brother of a friend of my deceased husband. He dashed my hopes of crossing the border in Bregenz or Lustenau. The only possibility he saw was Hohenems, if I could find a guide there.”[2]

Paula Brecher goes to Hohenems to see Dr. Neudörfer, the head physician at the hospital, who has repeatedly helped refugees – even though he himself is at risk due to his Jewish ancestry. But in Hohenems she is passed around like a hot potato. Just three weeks ago, five women from Berlin failed in their attempt to escape at the border. One of them took her own life in Hohenems and died in Neudörfer's clinic. The Hohenems escape helpers were interrogated, the Diepoldsau escape helpers arrested in Switzerland. No one wants to accompany Paula Brecher to the border, only good advice is given as to which route she should take.

She does not find the recommended route. But in the middle of the night, at 2.30 a.m., she manages to get past the barbed wire fence in front of the Diepoldsau swimming pool. She sneaks along the wire fence of the swimming pool, crosses a shallow body of water north of the pool and is soon stopped by a Swiss border guard.

She has made it to Switzerland. However, her ordeal is not over yet. She is initially held in the St. Gallen police prison, until June 19th. She is then transferred to a Jewish girls' home in Basel, which now serves as refugee accommodation.

Just one day later, her parents are forced to leave Vienna. They are deported to Theresienstadt on June 20 on “Transport IV/1”. Moritz Rehberger, who was 44 years old when he went to fight for Austria in the First World War, perished in Theresienstadt on April 6, 1943. Paula's mother, Rosalie Rehberger survived in Theresienstadt until May 15, 1944. Then, at the age of 72, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered in the gas chambers. Paula Brecher would only learn of all this, years later.

However, she too is now physically and mentally ailing. In July 1942, she is hospitalized with a recurrence of a stomach ulcer. Soon afterwards, her Zurich benefactor dies and with her any hope for an easier right to stay. Paula Brecher now depends on the support of the Jewish Refugee Aid organizations She is finally allowed to move into private accommodation in 1943. She makes contact with the Basel circle around the psychoanalyist Heinrich Meng, who treats her as a therapist. Meng also tries to get her translation jobs, that are not subject to the strict ban on work that she is otherwise obliged to observe.

Hundreds of pages of correspondence from the immigration police in Bern, the Jewish Refugee Aid and the cantonal authorities document her struggle for survival in the following years, begging letters for medically necessary treatment and to obtain residence and work permits, and finally to secure permanent asylum. She still regularly receives official demands to apply for a visa for further emigration. She is still only occasionally allowed to do small paid jobs, a few language lessons here, a few translation jobs there. In 1949, the canton of Basel still refuses to grant her permanent asylum due to her poor health and states of anxiety. Paula Brecher has to fill in the International Refugee Organization's questionnaire twice more, explaining why she neither wants to return to Austria nor is able to emigrate to the USA.

Even the federal immigration police in Bern are now more friendly than the cantonal police. The letters from Bern are usually signed with a rubber-stamped name, on behalf of the authority, the “Chief of the Police Department”. Since 1948, the stamped letters from Bern bear the evocative name “Angst”.

It is “Fräulein Dr. Angst” who has since taken over the Brecher file. With her support, the time had actually come in February 1950. Paula Brecher receives the redemptive decision to be allowed to stay.

1974 she dies in Basel and is buried in the Jewish cemetery.[3]

[1] Diepoldsau police station, report on illegal entry into Switzerland, interrogation transcript, May 31, 1942; Swiss Federal Archives, Bern, Dossier Paula Brecher (E4264#1985/196#3189*)

[3] For Paula Brecher's (née Rehberger) biography, see: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58484&tree=Hohenems