Margarethe Eder> November 9, 1942

29a Margarethe Eder

Under the suspicion of espionage: Margarethe Eder knows too much

Hohenems, November 9, 1942

A young woman looks down from the Schlossberg in Hohenems to the border on the old Rhine. Margarethe Eder has already looked around in Feldkirch, Bregenz and Lustenau to see where she could flee across the border. On October 15, the 20-year-old factory worker from Graz left her workplace near Altötting in Bavaria in a hurry - to avoid being arrested for making critical remarks about the regime. She reached Innsbruck by train via Salzburg. From there, she walked to Feldkirch to avoid being checked on the train. On November 9, she finally seeks her fortune in Hohenems.

When she was questioned two days later at the Diepoldsau police station, her feet were frozen. The policeman summarized her account of how she crossed the Rhine at the Tratthof, a farm next to the border:

“At 6 p.m. I turned towards the border, which I was apparently able to cross unhindered, because I suddenly found myself at a barbed wire fence, which I crawled through. I then walked forward a few more meters until I came to some water. Because of the darkness, I couldn't see how big it was, so I decided to wait until morning and then continue on in daylight. In the morning I saw that I was in a dry riverbed, but at the same time I noticed border police patrolling both sides. By the ringing of the church bells, however, I soon recognized in which direction Switzerland might lie. I waited again until nightfall and crossed the water to get to the other side. Once there, I crossed a dam and soon came to a large barn, but it was locked. I therefore spent the night in the open again, in a hayloft. The next morning, on the 11th (of the month), I went to the next house, where I was picked up by the police.”[1]

A few days later, she is admitted to the cantonal hospital with first-degree frostbite.

At the police station in Diepoldsau, however, she also provides explosive information. She reports on the illegal production of poison gas bombs by Anorgana GmbH, under the guise of the Bavarian Nitrogen Works. And she also says that her father is a communist and is under close surveillance by the German authorities.

In January 1943, Margarethe Eder is sent to the Jakobsbad reception camp in Appenzell, and from there to the Gyrenbad refugee camp near Zurich.

On August 4, she is sent to Brissago. In the former Grand Hotel on Lake Maggiore, the Swiss authorities have set up a detention camp for women who have entered the country as political refugees. But Margarethe Eder does not arrive in Brissago. The Swiss immigration police assumes that she went to Italy illegally. But there is no proof of this.

However, there is evidence that Margarethe Eder was imprisoned in Klagenfurt in 1944. She was accused of espionage. On November 9, exactly two years after her escape to Switzerland, she was transferred to Berlin, to the prison in Moabit. Just a few days later, on November 14, 1944, she was sentenced to death on suspicion of espionage - and finally executed in Plötzensee on December 8. She left behind not only her parents in Graz, but also her husband, who was a soldier at the front, and her six-year-old daughter, whom she had given birth to at the age of just 15.

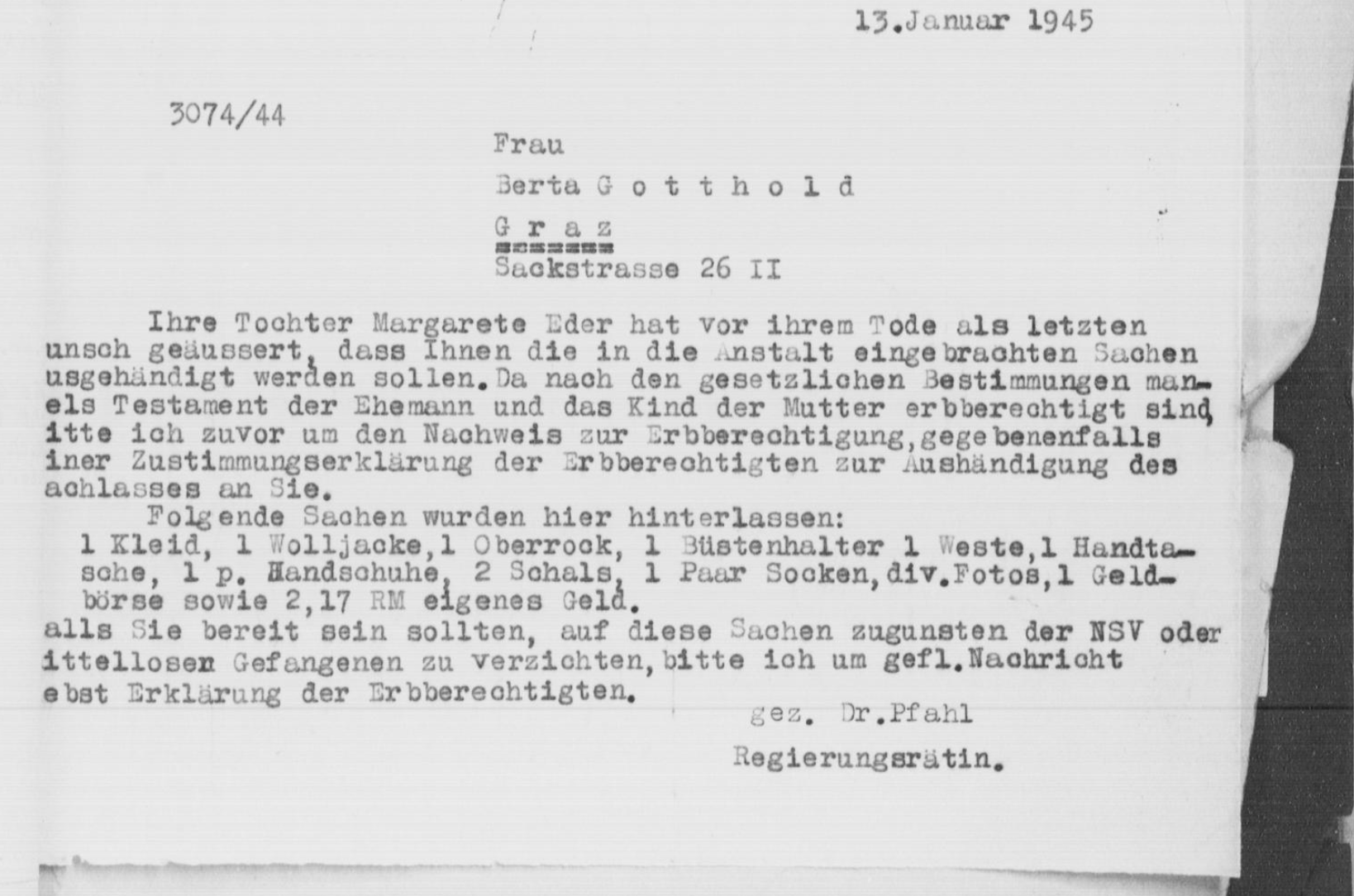

In January, her mother in Graz received a short message from Government Councillor Mrs. Dr. Pfahl in Berlin:

“Before her death, your daughter expressed the last wish that the things brought to the institution should be handed over to you. (...) The following items were left here:

1 dress, 1 woolen jacket, 1 overskirt, 1 brassiere, 1 vest, 1 handbag, 1 p. Gloves, 2 scarves, 1 pair of socks, various photos, 1 purse and 2,17 Reichsmark of her own money.

If you should be prepared to give up these items in favor of the National Socialist People's Welfare or destitute prisoners, please send me a message together with a declaration of the beneficiaries.”[2]

What the suspicion of espionage against Margarethe Eder actually consisted of is not clear from the scant documentation. Perhaps she simply knew too much.

The secret production of gas bombs was indeed carried out in Gendorf near Altötting. Under strict camouflage, the Wehrmacht had demanded the construction of “readiness facilities for army requirements” in 1938, meaning poison gas. Together with I.G. Farben, which initially resisted this order, mustard gas and the nerve poison Tabun were to be produced - poisonous gases that had had a terrible effect in the First World War, but had also caused countless deaths in their own ranks. In addition to German workers, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were also employed at the production site in Gendorf - under the guise of alleged detergent production. In September 1942, work began here on filling Tabun into bombs. Tabun was produced in the Dyhrenfurth subcamp of the Groß-Rosen concentration camp and the production of mustard gas also began in 1943.

Many of the concentration camp prisoners deployed there perished under the inhumane working conditions. The prisoners of war, who were also used to produce poison gas, were sent to the camp with the note “R.U.”. Return undesirable.

The Tabun bottled in Gendorf was never used during the war. It turned out that it decomposed by itself in the bombs and proved unusable at cold temperatures.[3]

[1] Rapport of the Policestation in Diepoldsau, November 11, 1942, Dossier Margarethe Eder, Bundesarchiv Bern.

[2] Regierungsrätin Dr. Pfahl to Berta Gottwald (falsely adressed as Berta Gotthold), January 13, 1945, Dossier Margarethe Eder/Walker, Arolsen Archives.

[3] More on Margarethe Eder: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58103&tree=Hohenems

29a Margarethe Eder

Under the suspicion of espionage: Margarethe Eder knows too much

Hohenems, November 9, 1942

A young woman looks down from the Schlossberg in Hohenems to the border on the old Rhine. Margarethe Eder has already looked around in Feldkirch, Bregenz and Lustenau to see where she could flee across the border. On October 15, the 20-year-old factory worker from Graz left her workplace near Altötting in Bavaria in a hurry - to avoid being arrested for making critical remarks about the regime. She reached Innsbruck by train via Salzburg. From there, she walked to Feldkirch to avoid being checked on the train. On November 9, she finally seeks her fortune in Hohenems.

When she was questioned two days later at the Diepoldsau police station, her feet were frozen. The policeman summarized her account of how she crossed the Rhine at the Tratthof, a farm next to the border:

“At 6 p.m. I turned towards the border, which I was apparently able to cross unhindered, because I suddenly found myself at a barbed wire fence, which I crawled through. I then walked forward a few more meters until I came to some water. Because of the darkness, I couldn't see how big it was, so I decided to wait until morning and then continue on in daylight. In the morning I saw that I was in a dry riverbed, but at the same time I noticed border police patrolling both sides. By the ringing of the church bells, however, I soon recognized in which direction Switzerland might lie. I waited again until nightfall and crossed the water to get to the other side. Once there, I crossed a dam and soon came to a large barn, but it was locked. I therefore spent the night in the open again, in a hayloft. The next morning, on the 11th (of the month), I went to the next house, where I was picked up by the police.”[1]

A few days later, she is admitted to the cantonal hospital with first-degree frostbite.

At the police station in Diepoldsau, however, she also provides explosive information. She reports on the illegal production of poison gas bombs by Anorgana GmbH, under the guise of the Bavarian Nitrogen Works. And she also says that her father is a communist and is under close surveillance by the German authorities.

In January 1943, Margarethe Eder is sent to the Jakobsbad reception camp in Appenzell, and from there to the Gyrenbad refugee camp near Zurich.

On August 4, she is sent to Brissago. In the former Grand Hotel on Lake Maggiore, the Swiss authorities have set up a detention camp for women who have entered the country as political refugees. But Margarethe Eder does not arrive in Brissago. The Swiss immigration police assumes that she went to Italy illegally. But there is no proof of this.

However, there is evidence that Margarethe Eder was imprisoned in Klagenfurt in 1944. She was accused of espionage. On November 9, exactly two years after her escape to Switzerland, she was transferred to Berlin, to the prison in Moabit. Just a few days later, on November 14, 1944, she was sentenced to death on suspicion of espionage - and finally executed in Plötzensee on December 8. She left behind not only her parents in Graz, but also her husband, who was a soldier at the front, and her six-year-old daughter, whom she had given birth to at the age of just 15.

In January, her mother in Graz received a short message from Government Councillor Mrs. Dr. Pfahl in Berlin:

“Before her death, your daughter expressed the last wish that the things brought to the institution should be handed over to you. (...) The following items were left here:

1 dress, 1 woolen jacket, 1 overskirt, 1 brassiere, 1 vest, 1 handbag, 1 p. Gloves, 2 scarves, 1 pair of socks, various photos, 1 purse and 2,17 Reichsmark of her own money.

If you should be prepared to give up these items in favor of the National Socialist People's Welfare or destitute prisoners, please send me a message together with a declaration of the beneficiaries.”[2]

What the suspicion of espionage against Margarethe Eder actually consisted of is not clear from the scant documentation. Perhaps she simply knew too much.

The secret production of gas bombs was indeed carried out in Gendorf near Altötting. Under strict camouflage, the Wehrmacht had demanded the construction of “readiness facilities for army requirements” in 1938, meaning poison gas. Together with I.G. Farben, which initially resisted this order, mustard gas and the nerve poison Tabun were to be produced - poisonous gases that had had a terrible effect in the First World War, but had also caused countless deaths in their own ranks. In addition to German workers, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were also employed at the production site in Gendorf - under the guise of alleged detergent production. In September 1942, work began here on filling Tabun into bombs. Tabun was produced in the Dyhrenfurth subcamp of the Groß-Rosen concentration camp and the production of mustard gas also began in 1943.

Many of the concentration camp prisoners deployed there perished under the inhumane working conditions. The prisoners of war, who were also used to produce poison gas, were sent to the camp with the note “R.U.”. Return undesirable.

The Tabun bottled in Gendorf was never used during the war. It turned out that it decomposed by itself in the bombs and proved unusable at cold temperatures.[3]

[1] Rapport of the Policestation in Diepoldsau, November 11, 1942, Dossier Margarethe Eder, Bundesarchiv Bern.

[2] Regierungsrätin Dr. Pfahl to Berta Gottwald (falsely adressed as Berta Gotthold), January 13, 1945, Dossier Margarethe Eder/Walker, Arolsen Archives.

[3] More on Margarethe Eder: https://www.hohenemsgenealogie.at/getperson.php?personID=I58103&tree=Hohenems