August Weiß> February 26, 1941

42a August Weiß

From Amerlügen to Aschendorfermoor - Moorsoldat No. 503/41 August Weiß

Frastanz, February 26, 1941

“My mother advised me to enlist again, but I refused. The next day, after dark, I planned to escape over the mountains to Liechtenstein. In civilian clothes and without papers, I was arrested by a patrol in Frastanz.”[1]

August Weiß from Dornbirn recalls his experience. As a 19-year-old, he was conscripted into the Wehrmacht on February 10, 1941 after several months of work service. But he didn't endure the barracks camp of the Salzburg mountain troops for long; he deserted, traveled to Carinthia and intended to escape to Yugoslavia. On the border, he gets a warning; two months before the German campaign in the Balkans, it is already clear in the air that the multi-ethnic state on the Adriatic will not remain a safe haven. Instead, the Vorarlberg native, who would later often describe himself as an “anti-militarist and internationalist”, [2] managed to return to his home town. While August Weiß still relied on the railroad for this journey to his mother, he probably took the bicycle for his escape attempt in the direction of Liechtenstein. And takes the route to Frastanz, even though the Swiss border on the Rhine would be much closer. But as a non-swimmer, August Weiß did not dare to cross the river.

His escape route took him to the Amerlügen hamlet above Frastanz, which at the time comprised just over 30 buildings. This included the small chapel 'Maria Opferung', where August Weiß was arrested, around 3 kilometers from the Liechtenstein border.

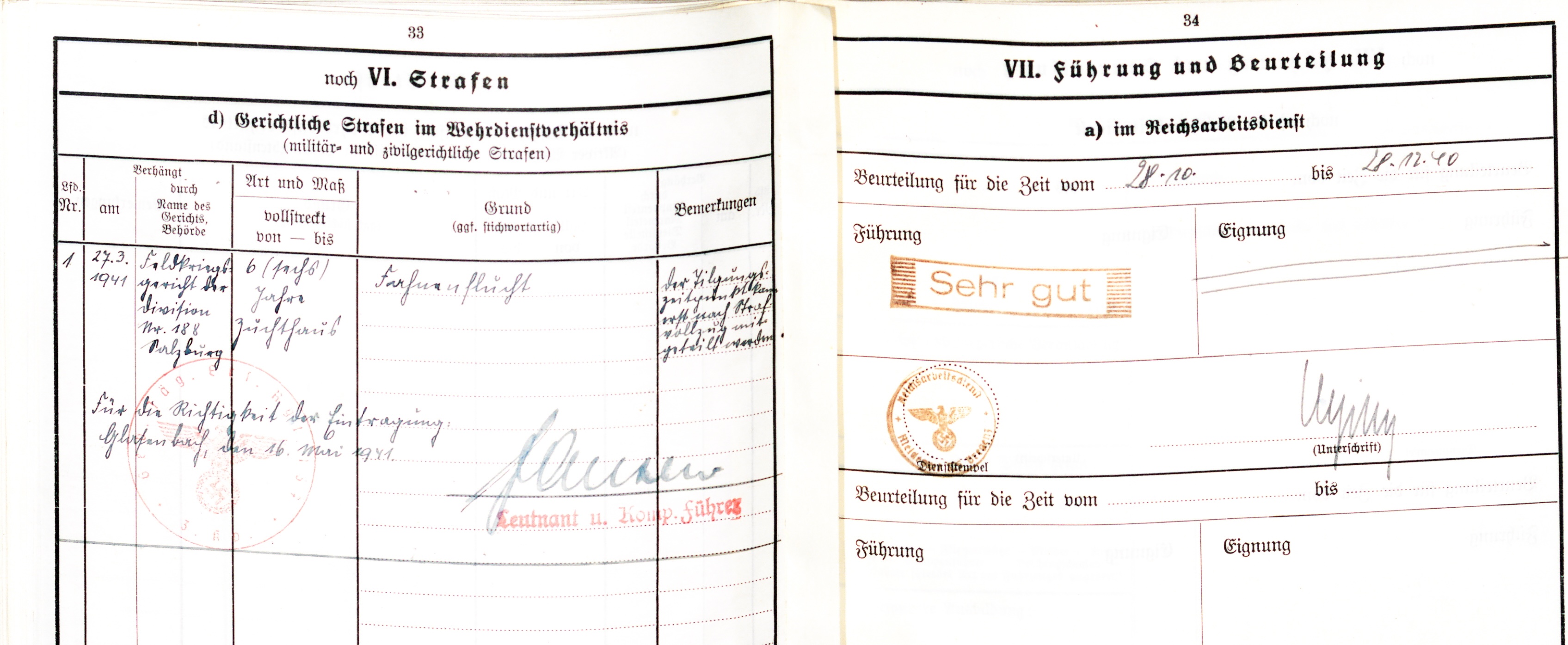

Back in Salzburg, he is put on trial before a military court. On March 27, 1941, Weiß is sentenced to six years in prison for 'desertion' and thus also loses his 'eligibility for military service'.

He was transferred from one prison to another several times before finding himself in the Aschendorfermoor prison camp, one of the notorious Emsland concentration camps, on June 5. As prisoner 503/41, he was one of over 1,000 prisoners who were not only forced to perform hard physical labor, but also suffered inadequate rations and beatings, which Weiß himself had to endure for 15 months. And even after that, freedom was still a long way off:

“I [was] transferred to the Wehrmacht prison Fort Zinna, Torgau, on September 1, 1942, where I remained imprisoned until November 30, 1942. My health, which had already been affected by the camp conditions in Aschendorfermoor, deteriorated rapidly in Torgau. Due to the miserable diet and the military harassment, I weighed only 35 kilos at the time of my release. I was 165 centimetres tall and my normal weight was 65 kilos.”[3]

Even the release mentioned by Weiß does not mean that he will return home. On December 1, 1942, he is handed over to the probationary battalion 500 in Fulda. Six months later, August Weiß is sent to the Eastern Front. Four wounds and a lengthy stay in a military hospital later, Weiß experienced the end of the war as a prisoner of Czech partisans. It was not until October 17, 1946, three weeks after his 25th birthday, that Weiß finally stood in front of his parents' house in Dornbirn's Schillerstrasse again after being released from Soviet captivity.

“After my return to Austria, I worked as a construction worker and later at the Zumtobel lighting company, where I was also a member of the workers council. I largely avoided talking about my desertion and developed the virtue of silence. It was only decades later [...] that I spoke about my experiences at a few schools.”[4]

This step into the public eye is due not least to the Johann August Malin Society, which was founded in 1982. Around 40 years after the end of the war, five young historians from its circle joined efforts to investigate the topics of persecution and resistance in Vorarlberg during the Nazi era. They published their findings in 1985 in the book “Von Herren und Menschen” (“Of Masters and Men”), which brought August Weiß and his deserter story to the attention of the general public for the first time. However, it was not completely unknown in parts of the population even before that. His sons' memories of threatening phone calls at night bear witness to this; a symptom of the debates characterized by prejudice and exclusion in a society in which deserters remained ostracized until the end of the last century. At the turn of the millennium Research projects at the University of Vienna, with Vorarlberg participation, but also the commitment of individuals and political parties, finally ensured that the first deserters were finally compensated for the persecution they had suffered.

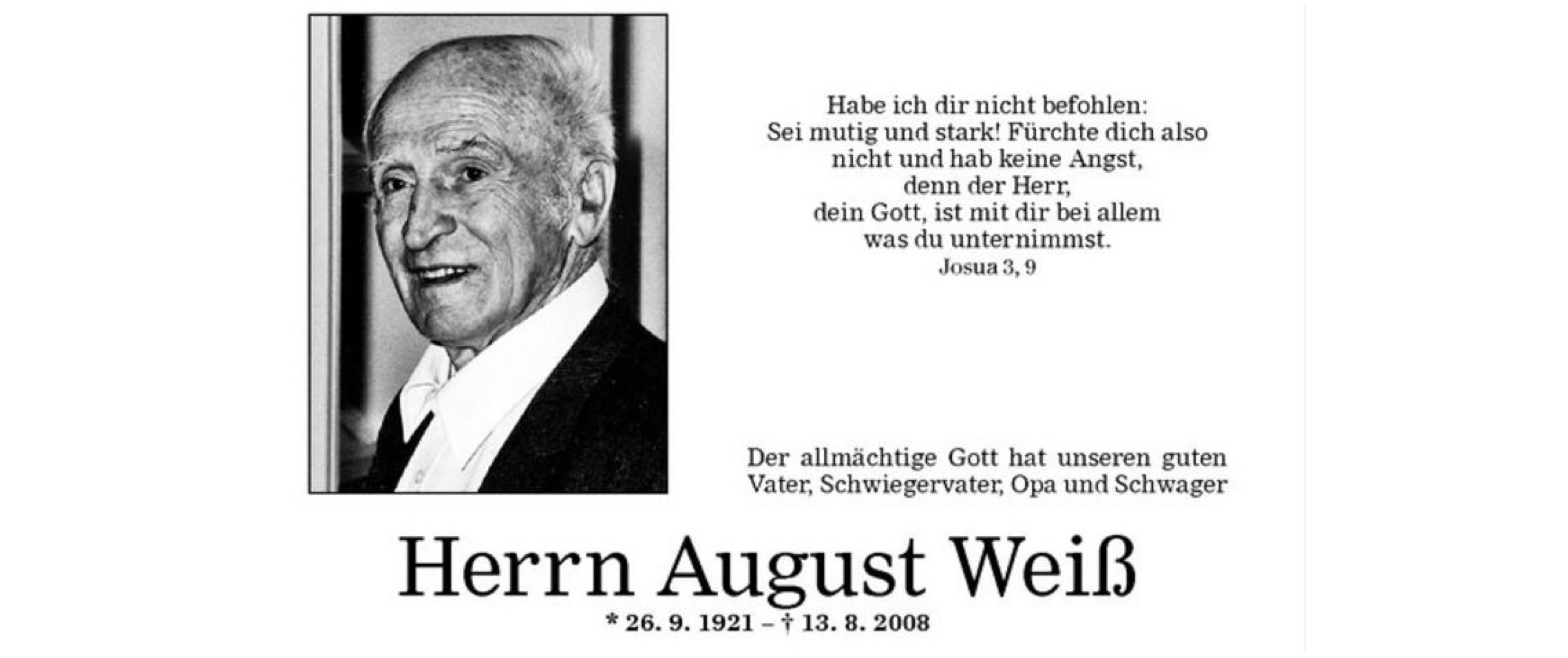

Among them was August Weiß, who was recognized as a victim of National Socialism in October 2000. It was to take even longer before he was fully rehabilitated. It was not until December 1, 2009 that the 'Repeal and Rehabilitation Act' came into force. But August Weiß did not live to see it. He died in Dornbirn on August 13, 2008.

The politics of remembrance, dealing with deserters, set visible signs in the following years. August Weiß, who as a contemporary witness was still committed to this himself during his school visits and interviews, is now commemorated in several places. In October 2014, Austria's first deserter memorial was inaugurated on Ballhausplatz in Vienna, followed by the resistance and deserter memorial on Sparkassenplatz in Bregenz in November 2015. Since 2011, the Emsland Camp Documentation and Information Center in Papenburg, Germany, has been commemorating the fate of August Weiß as well as many others.

Links:

Deserteursdenkmal Wien: https://deserteursdenkmal.at

Widerstandsmahnmal Bregenz: https://widerstandsmahnmal-bregenz.at

Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum Emslandlager: https://diz-emslandlager.de

Recommended reading:

Hannes Metzler, „Die Opfer erzählen. ‚Soldaten, die einfach nicht im Gleichschritt marschiert sind …‘ Zeitzeugeninterviews mit Überlebenden der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit“, in: Walter Manoschek (Ed.), Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich. Wien 2003, p. 494–603.

Werner Bundschuh, „August Weiß (1921-2008) – Moorsoldat Nr. 503/41: ‚Es soll keiner mehr das erleben, was ich erlebt habe‘“, in: Hanno Platzgummer/Karin Bitschnau/Werner Bundschuh (Ed.), „Ich kann einem Staat nicht dienen der schuldig ist…“. Vorarlberger vor den Gerichten der Wehrmacht. Dornbirn 2011, p. 37–50.

„Egon Weiß, 503/41 – eine Nummer im Moor. Mein Vater, der Wehrmachtsdeserteur August Weiß“, in: Juliane Alton/Thomas Geldmacher/Magnus Koch/Hannes Metzler (Ed.), „Verliehen für die Flucht vor den Fahnen“. Das Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Militärjustiz in Wien. Göttingen 2016, p. 210–219.

[1] From the self-written short biography of August Weiß, see: Hannes Metzler, „Die Opfer erzählen. ‚Soldaten, die einfach nicht im Gleichschritt marschiert sind …‘ Zeitzeugeninterviews mit Überlebenden der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit, in: Walter Manoschek (Ed.), Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich. Wien 2003, p. 494–603, here p. 597.

42a August Weiß

From Amerlügen to Aschendorfermoor - Moorsoldat No. 503/41 August Weiß

Frastanz, February 26, 1941

“My mother advised me to enlist again, but I refused. The next day, after dark, I planned to escape over the mountains to Liechtenstein. In civilian clothes and without papers, I was arrested by a patrol in Frastanz.”[1]

August Weiß from Dornbirn recalls his experience. As a 19-year-old, he was conscripted into the Wehrmacht on February 10, 1941 after several months of work service. But he didn't endure the barracks camp of the Salzburg mountain troops for long; he deserted, traveled to Carinthia and intended to escape to Yugoslavia. On the border, he gets a warning; two months before the German campaign in the Balkans, it is already clear in the air that the multi-ethnic state on the Adriatic will not remain a safe haven. Instead, the Vorarlberg native, who would later often describe himself as an “anti-militarist and internationalist”, [2] managed to return to his home town. While August Weiß still relied on the railroad for this journey to his mother, he probably took the bicycle for his escape attempt in the direction of Liechtenstein. And takes the route to Frastanz, even though the Swiss border on the Rhine would be much closer. But as a non-swimmer, August Weiß did not dare to cross the river.

His escape route took him to the Amerlügen hamlet above Frastanz, which at the time comprised just over 30 buildings. This included the small chapel 'Maria Opferung', where August Weiß was arrested, around 3 kilometers from the Liechtenstein border.

Back in Salzburg, he is put on trial before a military court. On March 27, 1941, Weiß is sentenced to six years in prison for 'desertion' and thus also loses his 'eligibility for military service'.

He was transferred from one prison to another several times before finding himself in the Aschendorfermoor prison camp, one of the notorious Emsland concentration camps, on June 5. As prisoner 503/41, he was one of over 1,000 prisoners who were not only forced to perform hard physical labor, but also suffered inadequate rations and beatings, which Weiß himself had to endure for 15 months. And even after that, freedom was still a long way off:

“I [was] transferred to the Wehrmacht prison Fort Zinna, Torgau, on September 1, 1942, where I remained imprisoned until November 30, 1942. My health, which had already been affected by the camp conditions in Aschendorfermoor, deteriorated rapidly in Torgau. Due to the miserable diet and the military harassment, I weighed only 35 kilos at the time of my release. I was 165 centimetres tall and my normal weight was 65 kilos.”[3]

Even the release mentioned by Weiß does not mean that he will return home. On December 1, 1942, he is handed over to the probationary battalion 500 in Fulda. Six months later, August Weiß is sent to the Eastern Front. Four wounds and a lengthy stay in a military hospital later, Weiß experienced the end of the war as a prisoner of Czech partisans. It was not until October 17, 1946, three weeks after his 25th birthday, that Weiß finally stood in front of his parents' house in Dornbirn's Schillerstrasse again after being released from Soviet captivity.

“After my return to Austria, I worked as a construction worker and later at the Zumtobel lighting company, where I was also a member of the workers council. I largely avoided talking about my desertion and developed the virtue of silence. It was only decades later [...] that I spoke about my experiences at a few schools.”[4]

This step into the public eye is due not least to the Johann August Malin Society, which was founded in 1982. Around 40 years after the end of the war, five young historians from its circle joined efforts to investigate the topics of persecution and resistance in Vorarlberg during the Nazi era. They published their findings in 1985 in the book “Von Herren und Menschen” (“Of Masters and Men”), which brought August Weiß and his deserter story to the attention of the general public for the first time. However, it was not completely unknown in parts of the population even before that. His sons' memories of threatening phone calls at night bear witness to this; a symptom of the debates characterized by prejudice and exclusion in a society in which deserters remained ostracized until the end of the last century. At the turn of the millennium Research projects at the University of Vienna, with Vorarlberg participation, but also the commitment of individuals and political parties, finally ensured that the first deserters were finally compensated for the persecution they had suffered.

Among them was August Weiß, who was recognized as a victim of National Socialism in October 2000. It was to take even longer before he was fully rehabilitated. It was not until December 1, 2009 that the 'Repeal and Rehabilitation Act' came into force. But August Weiß did not live to see it. He died in Dornbirn on August 13, 2008.

The politics of remembrance, dealing with deserters, set visible signs in the following years. August Weiß, who as a contemporary witness was still committed to this himself during his school visits and interviews, is now commemorated in several places. In October 2014, Austria's first deserter memorial was inaugurated on Ballhausplatz in Vienna, followed by the resistance and deserter memorial on Sparkassenplatz in Bregenz in November 2015. Since 2011, the Emsland Camp Documentation and Information Center in Papenburg, Germany, has been commemorating the fate of August Weiß as well as many others.

Links:

Deserteursdenkmal Wien: https://deserteursdenkmal.at

Widerstandsmahnmal Bregenz: https://widerstandsmahnmal-bregenz.at

Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum Emslandlager: https://diz-emslandlager.de

Recommended reading:

Hannes Metzler, „Die Opfer erzählen. ‚Soldaten, die einfach nicht im Gleichschritt marschiert sind …‘ Zeitzeugeninterviews mit Überlebenden der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit“, in: Walter Manoschek (Ed.), Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich. Wien 2003, p. 494–603.

Werner Bundschuh, „August Weiß (1921-2008) – Moorsoldat Nr. 503/41: ‚Es soll keiner mehr das erleben, was ich erlebt habe‘“, in: Hanno Platzgummer/Karin Bitschnau/Werner Bundschuh (Ed.), „Ich kann einem Staat nicht dienen der schuldig ist…“. Vorarlberger vor den Gerichten der Wehrmacht. Dornbirn 2011, p. 37–50.

„Egon Weiß, 503/41 – eine Nummer im Moor. Mein Vater, der Wehrmachtsdeserteur August Weiß“, in: Juliane Alton/Thomas Geldmacher/Magnus Koch/Hannes Metzler (Ed.), „Verliehen für die Flucht vor den Fahnen“. Das Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Militärjustiz in Wien. Göttingen 2016, p. 210–219.

[1] From the self-written short biography of August Weiß, see: Hannes Metzler, „Die Opfer erzählen. ‚Soldaten, die einfach nicht im Gleichschritt marschiert sind …‘ Zeitzeugeninterviews mit Überlebenden der NS-Militärgerichtsbarkeit, in: Walter Manoschek (Ed.), Opfer der NS-Militärjustiz. Urteilspraxis – Strafvollzug – Entschädigungspolitik in Österreich. Wien 2003, p. 494–603, here p. 597.