Kurt Neurath and Franz Hirschfeld> August/September 1938

42b Kurt Neurath and Franz Hirschfeld

Over the highest mountain in the Rätikon – Kurt Neurath and Franz Hirschfeld on the Schesaplana

Nenzing, August/September 1938

The scenes of March 15, 1938 on Vienna's Heldenplatz – Heroes’ Square - are familiar from television documentaries on National Socialism in Austria. Many photographs show the view from the lectern on the altan on the side of the Neue Hofburg, that’s still widely referred to as 'Hitler’s balcony'. It’s the view of a mass of more than 200,000 people cheering on their 'Führer' three days after the so-called 'Anschluss' to Nazi Germany. Nazi propaganda ensured that the footage of their 'liberation rally' went around the world in sound and vision.

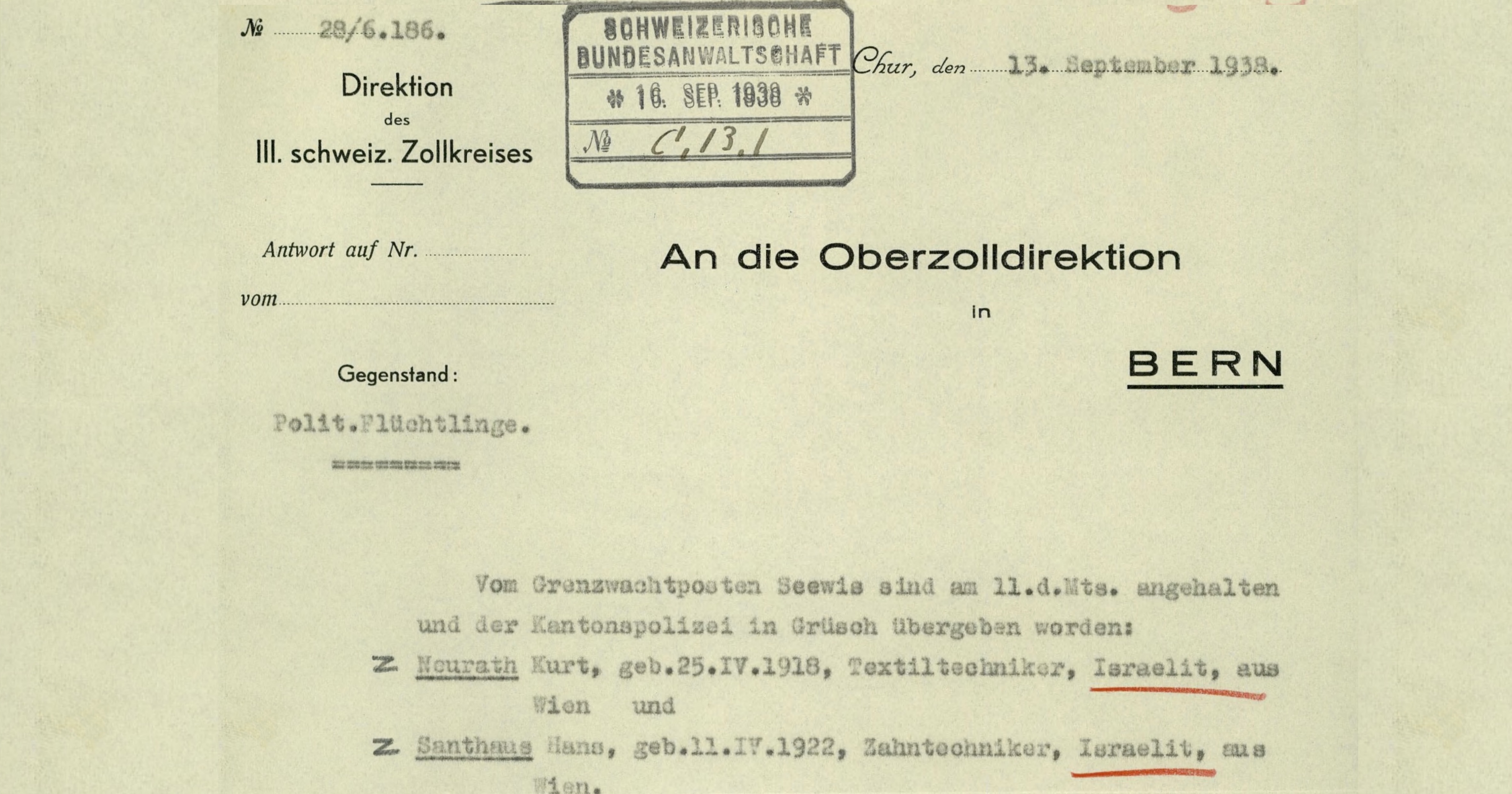

For another tenth of the almost two million Viennese, however, these days in March marked the start of the deprivation of their rights - of their dehumanization. Tens of thousands of Viennese Jews were driven to their deaths by the National Socialist regime in the years that followed, while around 150,000 others fled Vienna. Many of them made their way to Switzerland via Vorarlberg. Some, however, chose rather unusual routes, such as the textile technician Kurt Neurath. When he set off in the late summer of 1938, he had already endured several harassing arrests. But he was always released again. The terror finally had the desired effect on him too: he must escape.

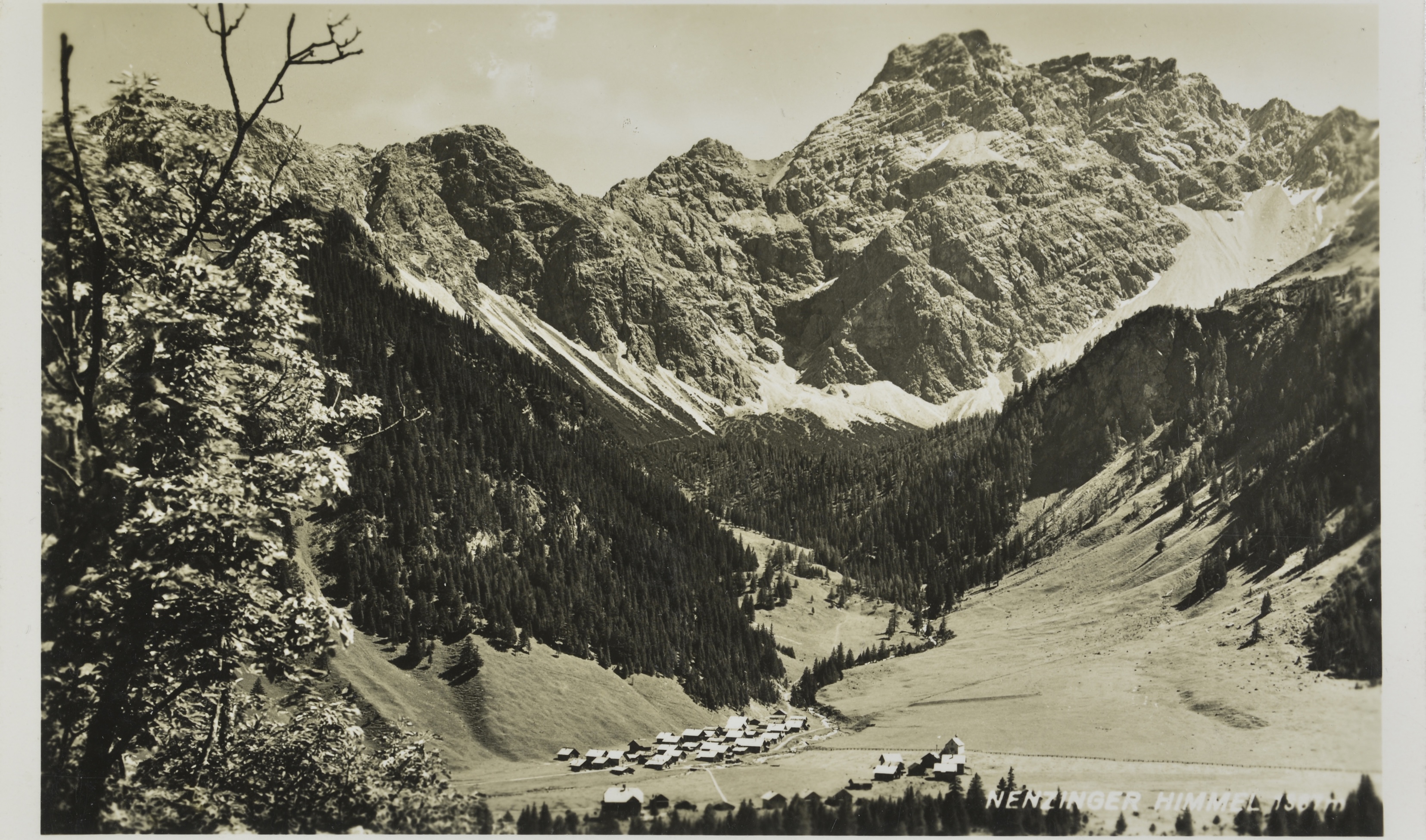

We do not know what prior knowledge Kurt Neurath had when planning his last few kilometers to the border. But it seems likely that he had already gained some mountain experience in his young life, because instead of traveling as far as the Rhine Valley like many others at the time, he got off the train in Nenzing. The Gamperdona valley lies ahead of him, opening up at the far end to the so called 'Nenzing heaven' and marking the border with Switzerland and Liechtenstein with its steep mountain slopes. More than 16 kilometers and around 850 meters in altitude have to be completed on the direct route to 'heaven', but the real challenge still lies ahead of Neurath. Later, he remembers having passed the highest mountain in the Rätikon range, the 2,965-metre-high Schesaplana. Neurath does not mention whether he actually climbs another 1,500 meters to the summit or whether he passes the border at another point, such as the Salaruel pass.

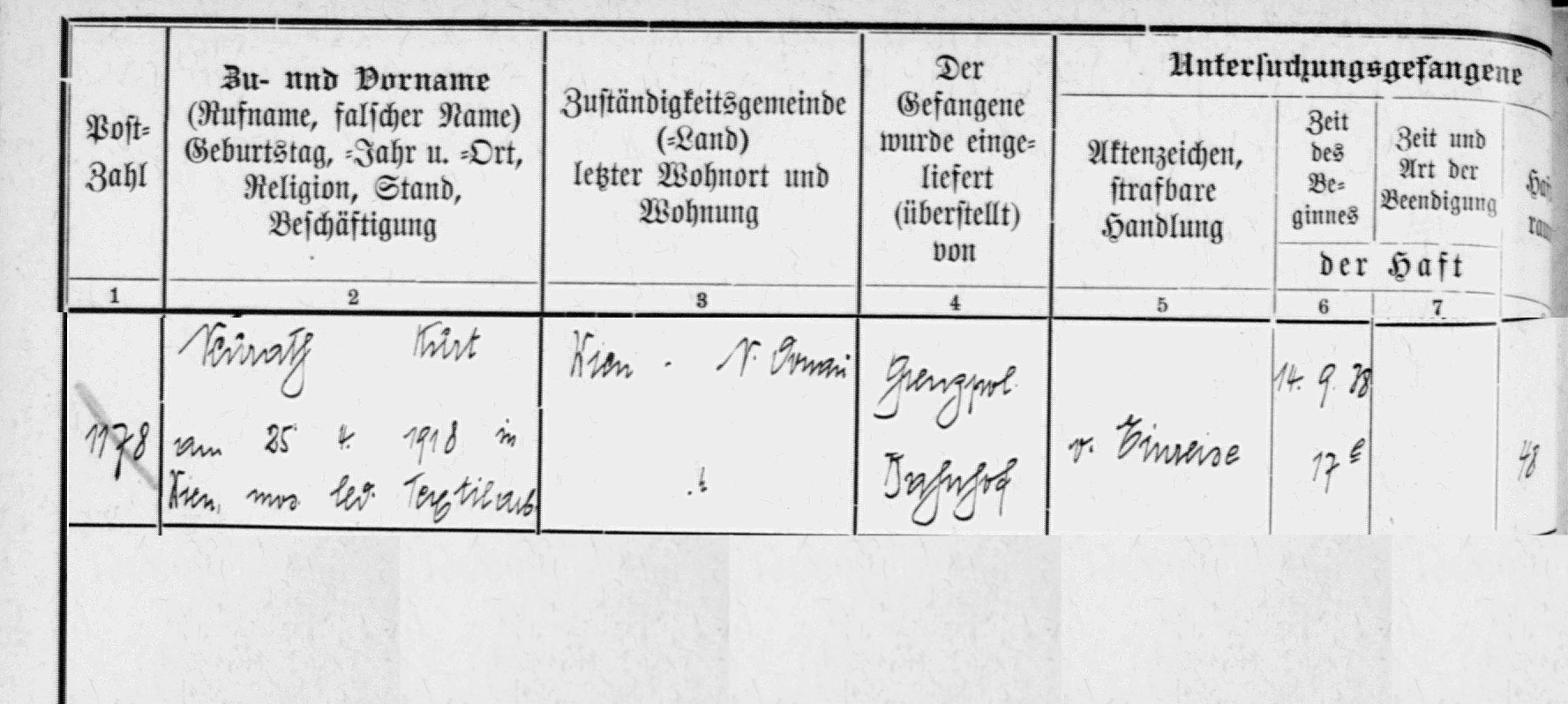

After the descent, he felt safe in Schiers in Switzerland, but the Swiss authorities refused to take him in. After a week in custody, he was handed over to the SS in Buchs, who took him back to Vorarlberg and sent him to the prison in Feldkirch. The prison register shows that the door to prison room no. 48 closes behind him at 5 p.m. on September 14. Exactly two weeks later, however, this prison stay also ended and Kurt Neurath had to return to Vienna.

Two months later, he contacted the emigration department of the Jewish Community in Vienna. Like many others, he asked for help to emigrate to a safe country. He names Shanghai as his destination and his application is granted. But instead of China, he traveled to Sweden six months later. He had managed to obtain a visa there.

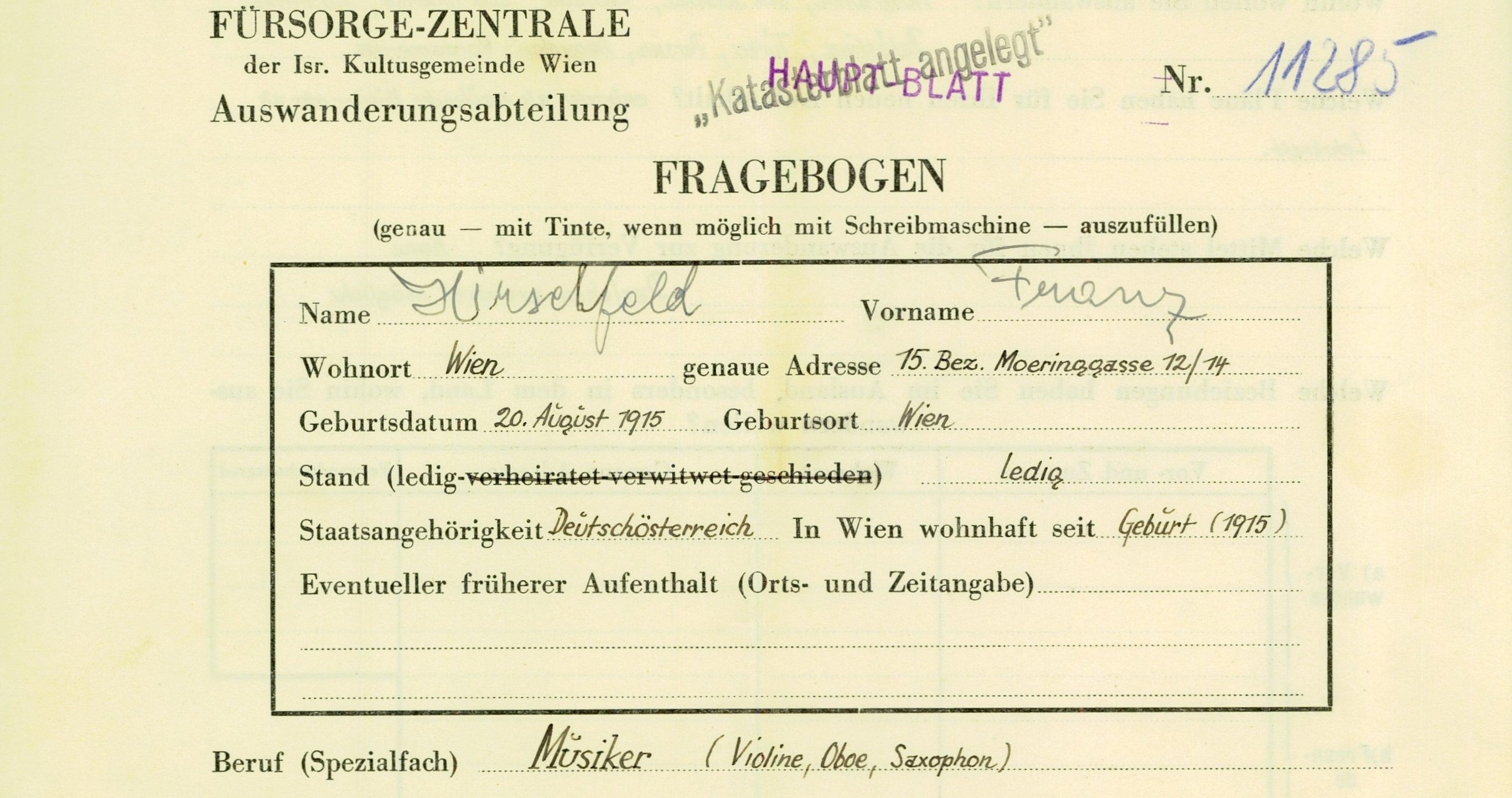

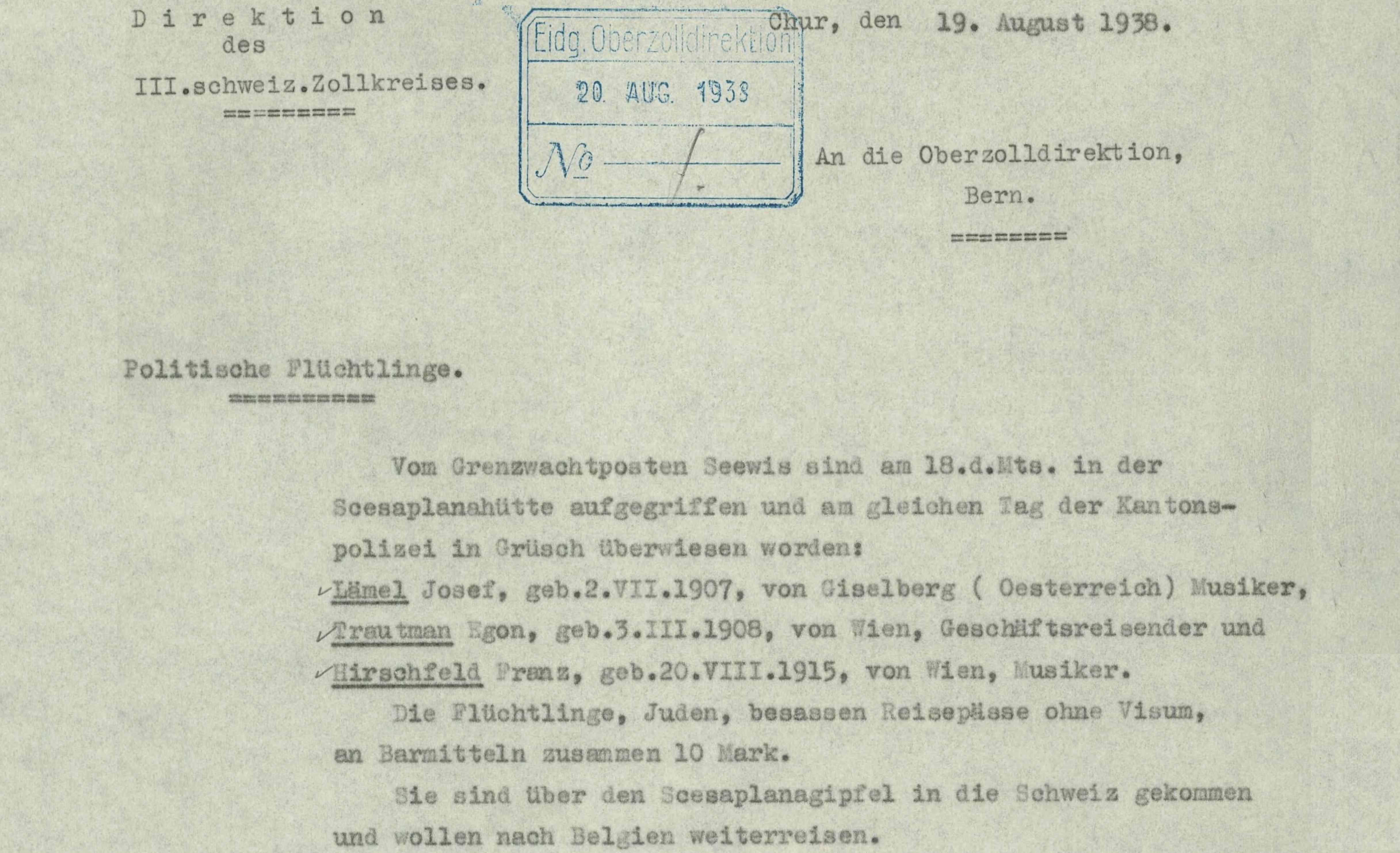

Two weeks before Kurt Neurath, Franz Hirschfeld, born in Vienna in 1915, also crossed the Schesaplana range. Together with two older fellow musicians from Vienna. None of the three were interested in the view, which on a clear day extends far beyond Lake Constance. Instead, they descend quickly and unseen into the Swiss Prättigau region. 1,000 meters below the summit, they stop off at the Schesaplana hut. A Swiss border guard soon becomes aware of them and discovers that there are no visa entries in the passports of the three Jewish refugees. On the same day, August 18, 1938, they were handed over to the cantonal police in Grüsch. Unlike Neurath, Hirschfeld is not deported; on August 24, he is already registered with the Zurich residents' registration office and is allowed to stay:

“As a result of the events of 1938 in Austria, I left this country at that time, initially with the intention of emigrating overseas, but this subsequently turned out to be impossible due to the difficult circumstances. Due to my professional skills, I was soon involved in the work process, and then I got married to a Swiss woman, which made Switzerland [...] my real home.”[1]

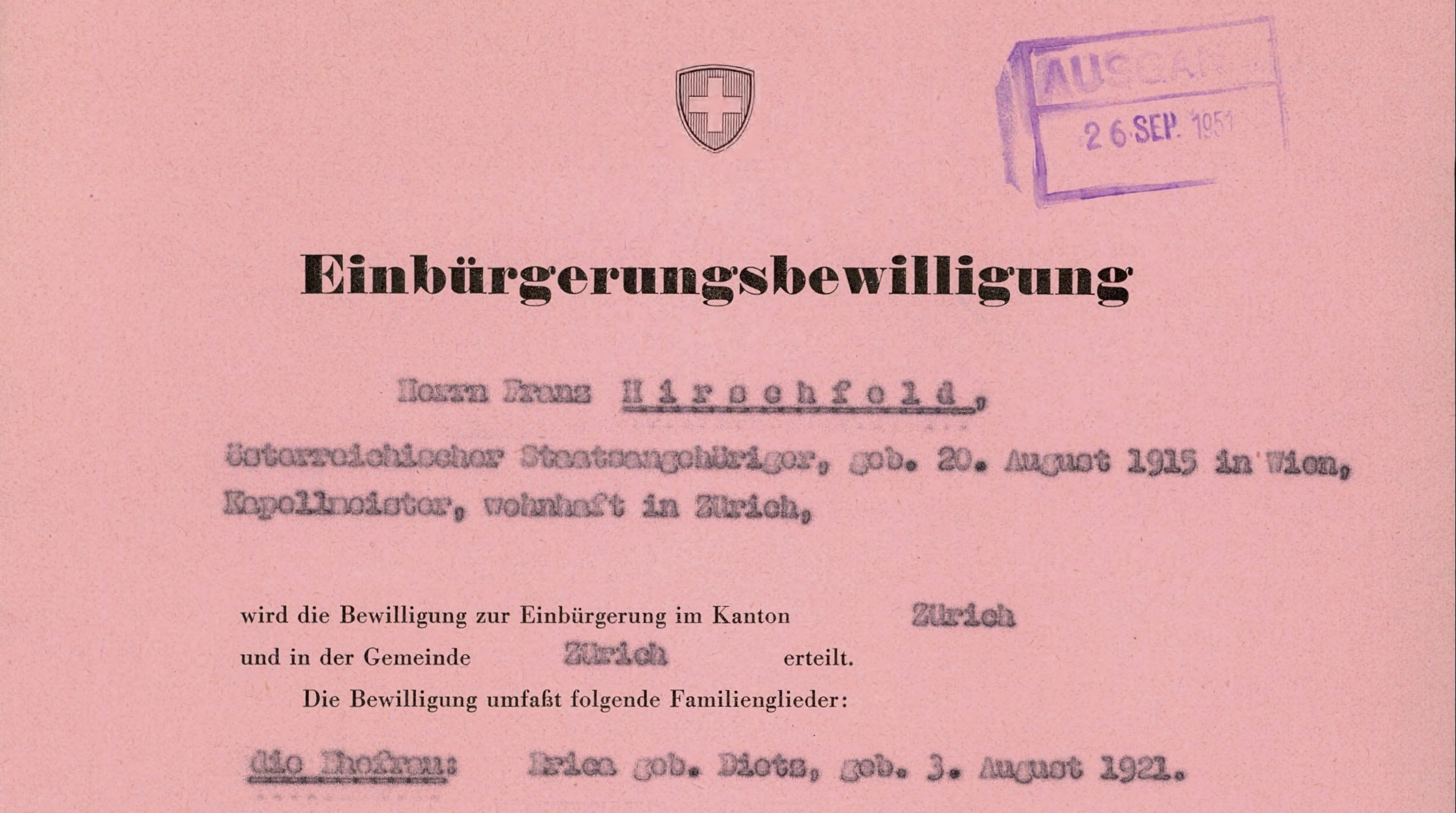

Hirschfeld addressed these lines to the Federal Department of Justice and Police in September 1949, when he applied for municipal and cantonal citizenship. He had already married the 22-year-old Erika Dietz in 1943. And his profession as a musician, in which he was soon allowed to work again, took him on trips all over Switzerland, such as to Basel, Locarno and Thun. His talent earned him performances lasting several months in concert venues of Bern and Geneva, as well as a job at the Hotel Silberhorn in Wengen.

Hirschfeld had studied the oboe with Professor Alexander Wunderer at the State Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna until 1938. But he was also proficient on the saxophone and violin. He had already played in several Viennese orchestras before his flight. His application for naturalization in Zurich was finally granted in 1951. Now a Swiss citizen, he remained a member of the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich for many decades and later married his colleague there, Margrit Essek. He died in Zurich in February 1990 at the age of 74.

And Kurt Neurath? He also married twice in his new, Swedish homeland, gained a foothold in his learned profession as a textile technician and reached the respectable age of 99. In 2014, he looked back on his life on behalf of the Austrian National Fund and concluded his memoirs with the words:

“In the first years of emigration and during the war years, I, like everyone else in my situation, constantly lived in fear. The worries for relatives and friends, but also homesickness, made a normal life impossible.”[2]

[1] Franz Hirschfeld in a letter to the Polizeiabteilung der Eidgenössischen Justiz und Polizeidepartements Bern, Zurich, September 19, 1949, see: Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv (BAR), E4264#2006/96#1380*.

[2] Kurt N. [Neurath], „So kam der März 1938“, in: Renate Meissner (Ed.), Erinnerungen. Lebensgeschichten von Opfern des Nationalsozialismus. Vienna 2014, p. 86-87, here p. 87.

42b Kurt Neurath and Franz Hirschfeld

Over the highest mountain in the Rätikon – Kurt Neurath and Franz Hirschfeld on the Schesaplana

Nenzing, August/September 1938

The scenes of March 15, 1938 on Vienna's Heldenplatz – Heroes’ Square - are familiar from television documentaries on National Socialism in Austria. Many photographs show the view from the lectern on the altan on the side of the Neue Hofburg, that’s still widely referred to as 'Hitler’s balcony'. It’s the view of a mass of more than 200,000 people cheering on their 'Führer' three days after the so-called 'Anschluss' to Nazi Germany. Nazi propaganda ensured that the footage of their 'liberation rally' went around the world in sound and vision.

For another tenth of the almost two million Viennese, however, these days in March marked the start of the deprivation of their rights - of their dehumanization. Tens of thousands of Viennese Jews were driven to their deaths by the National Socialist regime in the years that followed, while around 150,000 others fled Vienna. Many of them made their way to Switzerland via Vorarlberg. Some, however, chose rather unusual routes, such as the textile technician Kurt Neurath. When he set off in the late summer of 1938, he had already endured several harassing arrests. But he was always released again. The terror finally had the desired effect on him too: he must escape.

We do not know what prior knowledge Kurt Neurath had when planning his last few kilometers to the border. But it seems likely that he had already gained some mountain experience in his young life, because instead of traveling as far as the Rhine Valley like many others at the time, he got off the train in Nenzing. The Gamperdona valley lies ahead of him, opening up at the far end to the so called 'Nenzing heaven' and marking the border with Switzerland and Liechtenstein with its steep mountain slopes. More than 16 kilometers and around 850 meters in altitude have to be completed on the direct route to 'heaven', but the real challenge still lies ahead of Neurath. Later, he remembers having passed the highest mountain in the Rätikon range, the 2,965-metre-high Schesaplana. Neurath does not mention whether he actually climbs another 1,500 meters to the summit or whether he passes the border at another point, such as the Salaruel pass.

After the descent, he felt safe in Schiers in Switzerland, but the Swiss authorities refused to take him in. After a week in custody, he was handed over to the SS in Buchs, who took him back to Vorarlberg and sent him to the prison in Feldkirch. The prison register shows that the door to prison room no. 48 closes behind him at 5 p.m. on September 14. Exactly two weeks later, however, this prison stay also ended and Kurt Neurath had to return to Vienna.

Two months later, he contacted the emigration department of the Jewish Community in Vienna. Like many others, he asked for help to emigrate to a safe country. He names Shanghai as his destination and his application is granted. But instead of China, he traveled to Sweden six months later. He had managed to obtain a visa there.

Two weeks before Kurt Neurath, Franz Hirschfeld, born in Vienna in 1915, also crossed the Schesaplana range. Together with two older fellow musicians from Vienna. None of the three were interested in the view, which on a clear day extends far beyond Lake Constance. Instead, they descend quickly and unseen into the Swiss Prättigau region. 1,000 meters below the summit, they stop off at the Schesaplana hut. A Swiss border guard soon becomes aware of them and discovers that there are no visa entries in the passports of the three Jewish refugees. On the same day, August 18, 1938, they were handed over to the cantonal police in Grüsch. Unlike Neurath, Hirschfeld is not deported; on August 24, he is already registered with the Zurich residents' registration office and is allowed to stay:

“As a result of the events of 1938 in Austria, I left this country at that time, initially with the intention of emigrating overseas, but this subsequently turned out to be impossible due to the difficult circumstances. Due to my professional skills, I was soon involved in the work process, and then I got married to a Swiss woman, which made Switzerland [...] my real home.”[1]

Hirschfeld addressed these lines to the Federal Department of Justice and Police in September 1949, when he applied for municipal and cantonal citizenship. He had already married the 22-year-old Erika Dietz in 1943. And his profession as a musician, in which he was soon allowed to work again, took him on trips all over Switzerland, such as to Basel, Locarno and Thun. His talent earned him performances lasting several months in concert venues of Bern and Geneva, as well as a job at the Hotel Silberhorn in Wengen.

Hirschfeld had studied the oboe with Professor Alexander Wunderer at the State Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna until 1938. But he was also proficient on the saxophone and violin. He had already played in several Viennese orchestras before his flight. His application for naturalization in Zurich was finally granted in 1951. Now a Swiss citizen, he remained a member of the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich for many decades and later married his colleague there, Margrit Essek. He died in Zurich in February 1990 at the age of 74.

And Kurt Neurath? He also married twice in his new, Swedish homeland, gained a foothold in his learned profession as a textile technician and reached the respectable age of 99. In 2014, he looked back on his life on behalf of the Austrian National Fund and concluded his memoirs with the words:

“In the first years of emigration and during the war years, I, like everyone else in my situation, constantly lived in fear. The worries for relatives and friends, but also homesickness, made a normal life impossible.”[2]

[1] Franz Hirschfeld in a letter to the Polizeiabteilung der Eidgenössischen Justiz und Polizeidepartements Bern, Zurich, September 19, 1949, see: Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv (BAR), E4264#2006/96#1380*.

[2] Kurt N. [Neurath], „So kam der März 1938“, in: Renate Meissner (Ed.), Erinnerungen. Lebensgeschichten von Opfern des Nationalsozialismus. Vienna 2014, p. 86-87, here p. 87.