Heldsberg Fortress> 1938 - 1945

15 Heldsberg Fortress

Heldsberg fortress: underground positions against a German invasion

1938 to 1945

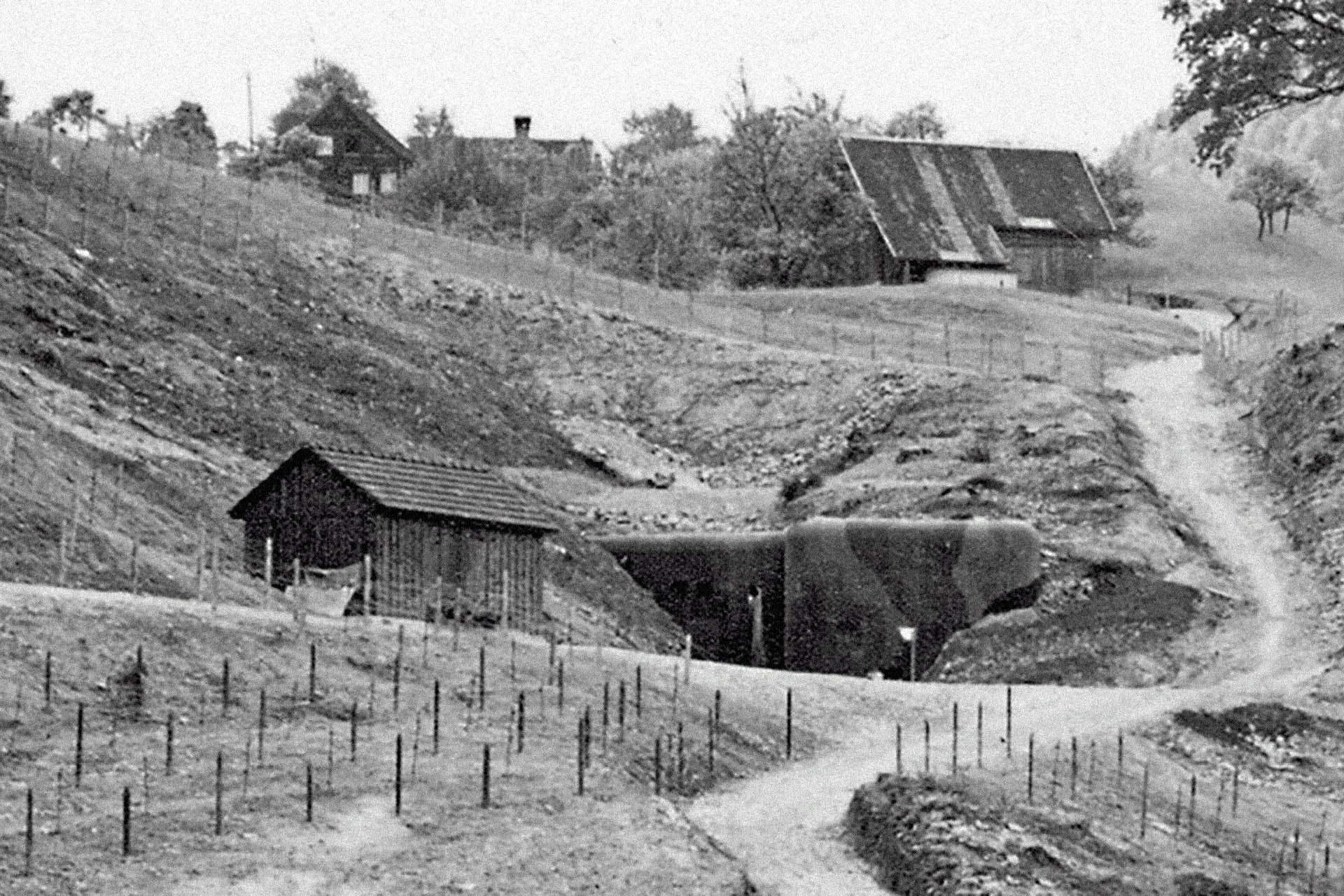

Switzerland prepared itself against a German invasion. On September 8, 1941, General Henri Guisan inspects the federal fortress structure Heldsberg, which extends underground for a kilometer under the last spur of the Swiss mountains above St. Margrethen.

Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Barbey, the general's chief of personal staff, records in his diary:

“In St. Margrethen, near the former Austrian border, Gubler, commander of Border Brigade 8, takes us to visit Fort Heldsberg, the northeastern spur of our border system. Surprising result today of certain pre-war decisions which provided for costly fortifications that are too far outlying as these are, which nevertheless have only a local importance.”[1]

The High Command of the German Wehrmacht apparently estimated the defense potential of the fortresses in the Rhine Valley somewhat higher. Since 1940, plans were being drawn up for a possible German invasion of Switzerland. After all, in May of that year, the Wehrmacht had already invaded two neutral states, Belgium and the Netherlands. The “Operation Draft for a German Attack against Switzerland” of August 26, 1940, prepared under the code name ”Tannenbaum” as a secret command document, already contained a precise overview of the Swiss fortifications and let it be known:

“An attack across the Rhine, only from an eastward direction between Lake Constance and Sargans, is not to be recommended because of the mountainous terrain and the strong fortifications at Rheineck and Sargans.”[2]

In any case, Switzerland's border fortifications were intended to hold off a possible German invasion for at least a few weeks and to secure the Swiss retreat into the Reduit, i.e., into the central Alpine region of Switzerland secured by massive fortifications, as envisaged by the operations order of July 12, 1940.

The planning of the Heldsberg fortress began in 1938 under the sign of the approaching war. It was completed in a short time between 1939 and 1941. Four fortress guns with a caliber of 7.5 cm, secured by seven machine gun emplacements and two observation posts, were directed to the north-east and south, at Bregenz and Lindau, at Hard and Fussach, the Rhine bridges, Lustenau, Dornbirn, and Hohenems. In addition, there were two dozen bunker positions in the Rhine Valley.

The fortress guns and machine gun emplacements, some of which were hidden behind innocent-looking facades of “single-family houses,” were connected underground by a system of tunnels and caverns, which included the sleeping and recreation rooms for the 200-man fortress crew, a military hospital, a kitchen, a large water reservoir, and a power plant that was to supply the entire fortification with electricity and fresh air as well as to prevent the possible penetration of battle gas into the bunkers by means of overpressure.

The fact that the Wehrmacht knew about the Swiss defense positions in detail was due to its successful espionage activities and probably also to not a few sympathizers of National Socialism in Switzerland.

In September 1939, one of the “traitors to the country” was arrested in Altstätten. This caused some excitement, because the non-commissioned officer M., who was himself employed in fortress construction, was a popular citizen of the Swiss town. In May 1939, M. confessed in custody after a first trial to the prison administrator in the Thurgau prison of Tobel, a sportily dressed German, allegedly named “Müller”, had invited him on the main street of Altstätten to a beer in the restaurant Drei König – and had persuaded him to deliver copies of the armoring plans of the bunkers on the Stoss and on the Landmark, for ”compensation” of 100 Reichsmark per photograph. It remained open why the German agent of the Abwehr branch office in Bregenz was able to recognize and approach the traitor M. in Altstätten in such a targeted manner.

In any case, in his closing statement in a second trial in 1940, M. claimed:

“I never thought that the political situation could be as serious as it is today. Most certainly I did not want to harm Switzerland intentionally. I committed my crime only for the money, since I was in a depressed situation financially. I would like to state here in particular that I have never sympathized with the system in Germany.”[3]

The Wehrmacht's plans to conquer Switzerland simultaneously from France, from the north and east, and with Italian forces from the south – and to divide its garrison afterwards between Germany and Italy along a border of interests between Lake Geneva and Sargans, all remained mind games.

Neutral Switzerland, as a hub of banking and money flows, secure traffic routes between the German Reich and Italy, as a place for discreet talks and negotiations behind the scenes about raw material supplies and much more, all this was obviously more valuable to the National Socialists than a risky and dearly fought conquest without strategic benefit.

Around 1990 the Heldsberg fortress was abandoned by the Swiss Army. In 1993 it was decided to establish a museum in it, today's Heldsberg Fortress Museum. By now, the view across the Rhine to the north over the wooded ridge of the hill shows hardly visible traces of the fortress architecture. You have to look closely to make out the concrete bunkers between trees and bushes. And to this day, cannon emplacements are hidden behind the mock facades of single-family homes in the grove above the Swiss highway, recognizable at best by a strange window shape on the first floor.

[1] Die Festung Heldsberg St. Margrethen. Vom Festungswerk zum Museum. Rheintaler Volksfreund: Au, not dated, p. 14-15.

[3] ibid, p. 23

15 Heldsberg Fortress

Heldsberg fortress: underground positions against a German invasion

1938 to 1945

Switzerland prepared itself against a German invasion. On September 8, 1941, General Henri Guisan inspects the federal fortress structure Heldsberg, which extends underground for a kilometer under the last spur of the Swiss mountains above St. Margrethen.

Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Barbey, the general's chief of personal staff, records in his diary:

“In St. Margrethen, near the former Austrian border, Gubler, commander of Border Brigade 8, takes us to visit Fort Heldsberg, the northeastern spur of our border system. Surprising result today of certain pre-war decisions which provided for costly fortifications that are too far outlying as these are, which nevertheless have only a local importance.”[1]

The High Command of the German Wehrmacht apparently estimated the defense potential of the fortresses in the Rhine Valley somewhat higher. Since 1940, plans were being drawn up for a possible German invasion of Switzerland. After all, in May of that year, the Wehrmacht had already invaded two neutral states, Belgium and the Netherlands. The “Operation Draft for a German Attack against Switzerland” of August 26, 1940, prepared under the code name ”Tannenbaum” as a secret command document, already contained a precise overview of the Swiss fortifications and let it be known:

“An attack across the Rhine, only from an eastward direction between Lake Constance and Sargans, is not to be recommended because of the mountainous terrain and the strong fortifications at Rheineck and Sargans.”[2]

In any case, Switzerland's border fortifications were intended to hold off a possible German invasion for at least a few weeks and to secure the Swiss retreat into the Reduit, i.e., into the central Alpine region of Switzerland secured by massive fortifications, as envisaged by the operations order of July 12, 1940.

The planning of the Heldsberg fortress began in 1938 under the sign of the approaching war. It was completed in a short time between 1939 and 1941. Four fortress guns with a caliber of 7.5 cm, secured by seven machine gun emplacements and two observation posts, were directed to the north-east and south, at Bregenz and Lindau, at Hard and Fussach, the Rhine bridges, Lustenau, Dornbirn, and Hohenems. In addition, there were two dozen bunker positions in the Rhine Valley.

The fortress guns and machine gun emplacements, some of which were hidden behind innocent-looking facades of “single-family houses,” were connected underground by a system of tunnels and caverns, which included the sleeping and recreation rooms for the 200-man fortress crew, a military hospital, a kitchen, a large water reservoir, and a power plant that was to supply the entire fortification with electricity and fresh air as well as to prevent the possible penetration of battle gas into the bunkers by means of overpressure.

The fact that the Wehrmacht knew about the Swiss defense positions in detail was due to its successful espionage activities and probably also to not a few sympathizers of National Socialism in Switzerland.

In September 1939, one of the “traitors to the country” was arrested in Altstätten. This caused some excitement, because the non-commissioned officer M., who was himself employed in fortress construction, was a popular citizen of the Swiss town. In May 1939, M. confessed in custody after a first trial to the prison administrator in the Thurgau prison of Tobel, a sportily dressed German, allegedly named “Müller”, had invited him on the main street of Altstätten to a beer in the restaurant Drei König – and had persuaded him to deliver copies of the armoring plans of the bunkers on the Stoss and on the Landmark, for ”compensation” of 100 Reichsmark per photograph. It remained open why the German agent of the Abwehr branch office in Bregenz was able to recognize and approach the traitor M. in Altstätten in such a targeted manner.

In any case, in his closing statement in a second trial in 1940, M. claimed:

“I never thought that the political situation could be as serious as it is today. Most certainly I did not want to harm Switzerland intentionally. I committed my crime only for the money, since I was in a depressed situation financially. I would like to state here in particular that I have never sympathized with the system in Germany.”[3]

The Wehrmacht's plans to conquer Switzerland simultaneously from France, from the north and east, and with Italian forces from the south – and to divide its garrison afterwards between Germany and Italy along a border of interests between Lake Geneva and Sargans, all remained mind games.

Neutral Switzerland, as a hub of banking and money flows, secure traffic routes between the German Reich and Italy, as a place for discreet talks and negotiations behind the scenes about raw material supplies and much more, all this was obviously more valuable to the National Socialists than a risky and dearly fought conquest without strategic benefit.

Around 1990 the Heldsberg fortress was abandoned by the Swiss Army. In 1993 it was decided to establish a museum in it, today's Heldsberg Fortress Museum. By now, the view across the Rhine to the north over the wooded ridge of the hill shows hardly visible traces of the fortress architecture. You have to look closely to make out the concrete bunkers between trees and bushes. And to this day, cannon emplacements are hidden behind the mock facades of single-family homes in the grove above the Swiss highway, recognizable at best by a strange window shape on the first floor.

[1] Die Festung Heldsberg St. Margrethen. Vom Festungswerk zum Museum. Rheintaler Volksfreund: Au, not dated, p. 14-15.

[3] ibid, p. 23