Diepoldsau refugee camp> 1938 - 1939

18 Diepoldsau refugee camp

Hunger strike and solidarity in the Diepoldsau refugee camp

Diepoldsau, 1938 to 1939

“Anyone who has business in the Diepoldsau-Widnau area at present will immediately notice the many foreign figures, mostly people aged 20-30, who populate the streetscape and are recognized at first glance as Jewish emigrants.”

The reporter in the St. Gall Tagblatt of 23 August 1938 does not hide his anti-Semitic resentment towards the people who were accommodated in the Diepoldsau refugee camp.

“A regular order has been introduced by the St. Gall police in the camp: people have to line up for the room control, roll call, checking shelves, etc. While these were quite strange things for most of the people at the beginning, today everyone seems to have got used to them well and recognizes the value of such order.“

One of those who had to ensure this order was Landjäger Ernst Kamm. In July, or even at the beginning of August, he had received an order from Captain Grüninger to set up a refugee camp in an empty embroidery shop in Diepoldsau. The spacious hall offered room for 300 people, under spartan conditions. Another building nearby was rented for families and a sick room was also set up there.

Ernst Kamm describes his experiences in 2000 in a conversation with David Bernet. Whether he could still remember numbers and dates correctly at the age of 92, however, remains an open question.

“In the middle of July 1938, Grüninger got me out of bed after a night shift and said: ‘You, Kamm, you have to go to Diepoldsau. We had 1,200 people who defected that night, Jewish refugees. You have to go to Diepoldsau. You must take over this camp. I'll give you four men to help you.’ I had to pack up immediately and he took me personally to Diepoldsau. He said, ‘There's an empty factory belonging to the Frey family, an old embroidery shop that had to be closed because of the bad times.’ No more orders, the war was just around the corner. Our camp in Diepoldsau was only 500 metres from the border. That's when he said, ‘You have to set up the camp, you're a technician’.”1

The costs for renting and setting up the camp, and even for guarding it by the cantonal police, have to be covered by Jewish Refugee Aid. And this organization is increasingly faced with the problem of collecting donations for the relief of a need that one hardly dares to talk about publicly. For fear of xenophobic reactions from the Swiss public. In the camp's common room, however, a large mural is emblazoned with the motto “Thanks to the Swiss people!”

Kamm, who is given command of the camp, is considered quite strict and authoritarian among the refugees. He himself recalls his conflicts of conscience.

“Yes, I was always in a very difficult position. Because I was in favor of helping and I shouldn't have been. Helping against the will of the law – that's a difficult position. In any case, where the husband and the son are already there and the wife is just coming, to finally solve that for the reception. You can't really imagine such a decision. To separate a family that has done nothing wrong. They haven't done anything wrong. They were persecuted. They fled from death, from the life that was to be taken from them.”

And he remembers the diversity in the camp:

“Among the emigrants who came, there were people from all walks of life. From the poor to people with good professions: Lawyers, dentists, doctors or film actors. Then came another saddler, a car mechanic, down to the unskilled worker, like us. The behavior of these people was very different. There were very helpful people. There were many who only did what they had to. At the most, they put their camp in order. Some were just waiting to leave.”

One of the many who sought shelter here was David Selig Scheer. Originally from Poland, he grew up in a Viennese orphanage and had kept his head above water as a construction worker. The other camp inmates remember him as a miserable figure. Even the refugee assistance does not like to take care of him. Apparently he was expelled several times, but nevertheless he managed to find admission to the camp in December 1938. A fellow inmate, Kurt Bettelheim remembers:

“Almost at the border there was a restaurant called ‘Alpenblick’, with whose owner we camp inmates had the best contact. Scheer arrived there on Christmas night, and the landlord called the St. Gall congregation and told the people there: ‘If you don't make sure that this man can stay in Switzerland, then I'll make sure that those you attach great importance to can't come either!’”2

Scheer can now indeed stay. And in the summer of 1939, the solidarity of the other internees once again prevents his expulsion. They go on hunger strike. The relationship between the camp inmates and the Jewish community remained conflictual. Some remember the subsequent appearance of the St. Gall community leader and president of the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities, Saly Mayer, in Diepoldsau:

“Gentlemen, I can inform you that there are still some places available in Dachau.”

It is the same Saly Mayer who is behind the scenes collecting money for the refugees and involved in secret rescue operations.

The internees are not allowed to work and support themselves. Some nevertheless find illegal work with people in Diepoldsau, many of whom are quite fond of the refugees.

The camp is closed in September 1939. The war had begun. Most of the refugees are now interned in labor camps.

Recommended reading:

Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998); Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005

[1] Interview by David Bernet with Ernst Kamm in Landquart, March 2000, for the Archimob project (Archives de la Mobilisation en Suisse 1939-1945).

[2] Quoted from: Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998), p. 93-94.

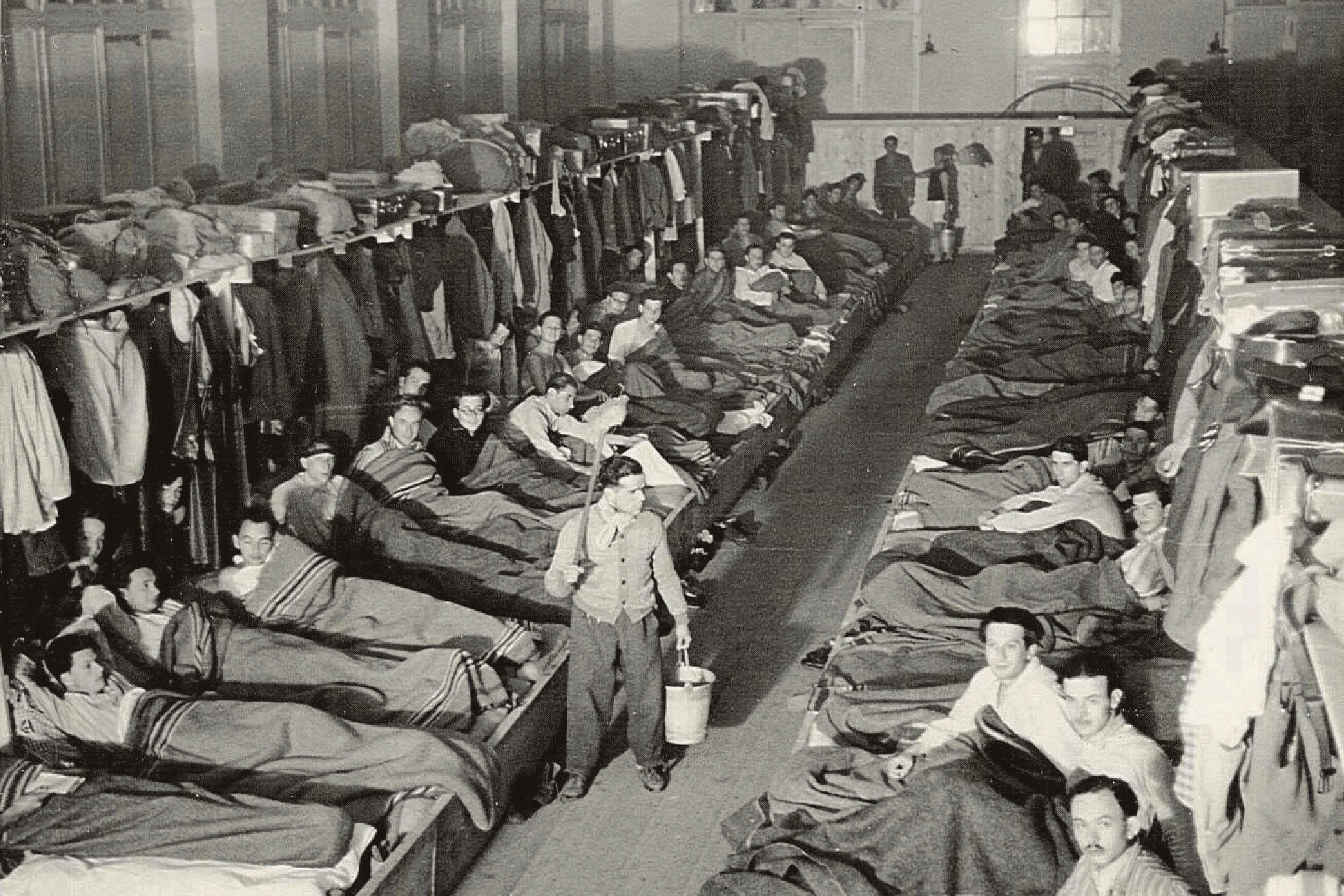

Common room in Diepoldsau camp, March 1939

Common room in Diepoldsau camp, March 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Schawuot in Diepoldsau camp, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

At Diepoldsau camp, 1939

At Diepoldsau camp, 1939

SIG Archiv 2539, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, Zürich

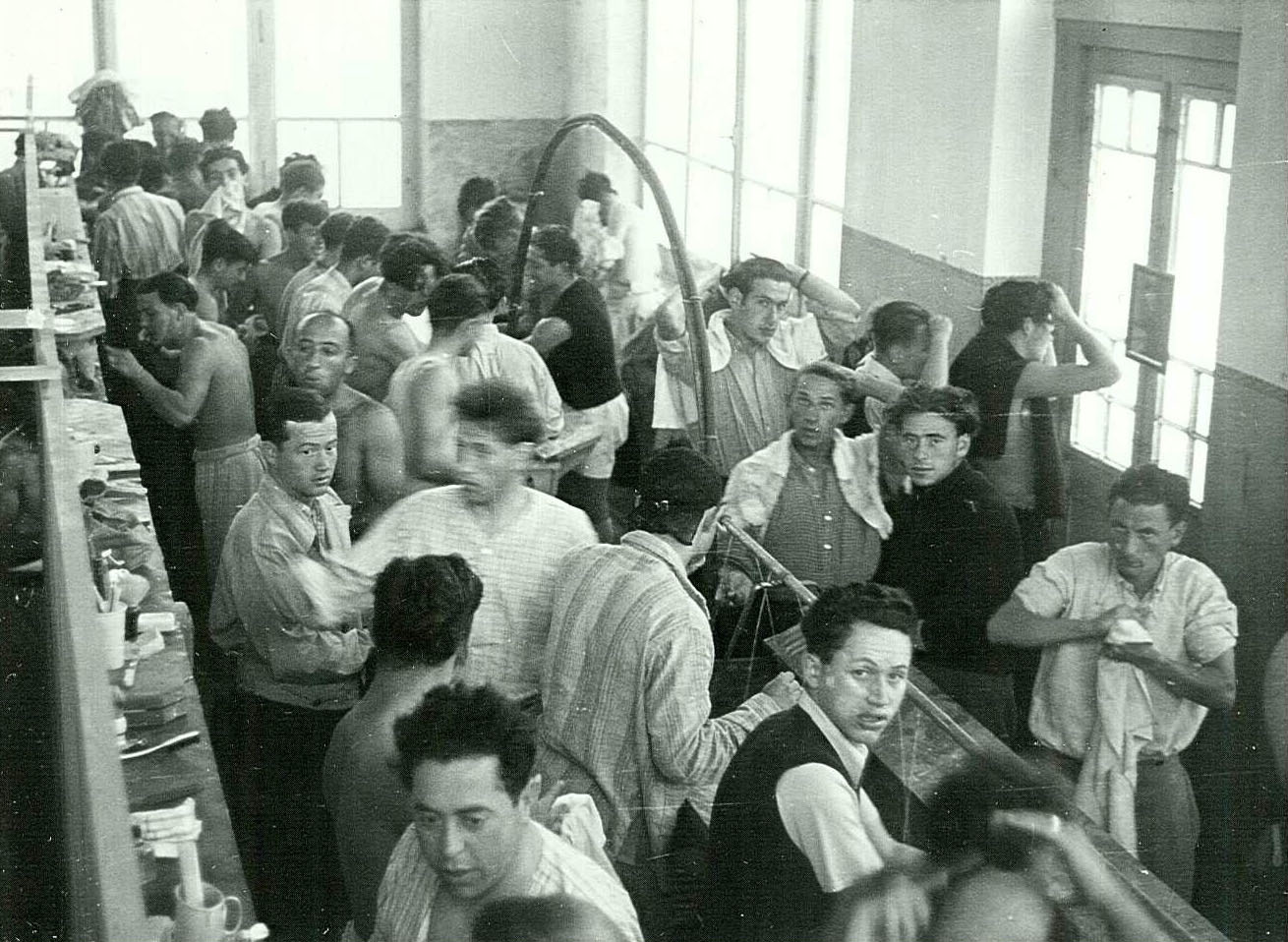

Washroom in Diepoldsau camp, 1939

Washroom in Diepoldsau camp, 1939

SIG Archiv 2539, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, Zürich

18 Diepoldsau refugee camp

Hunger strike and solidarity in the Diepoldsau refugee camp

Diepoldsau, 1938 to 1939

“Anyone who has business in the Diepoldsau-Widnau area at present will immediately notice the many foreign figures, mostly people aged 20-30, who populate the streetscape and are recognized at first glance as Jewish emigrants.”

The reporter in the St. Gall Tagblatt of 23 August 1938 does not hide his anti-Semitic resentment towards the people who were accommodated in the Diepoldsau refugee camp.

“A regular order has been introduced by the St. Gall police in the camp: people have to line up for the room control, roll call, checking shelves, etc. While these were quite strange things for most of the people at the beginning, today everyone seems to have got used to them well and recognizes the value of such order.“

One of those who had to ensure this order was Landjäger Ernst Kamm. In July, or even at the beginning of August, he had received an order from Captain Grüninger to set up a refugee camp in an empty embroidery shop in Diepoldsau. The spacious hall offered room for 300 people, under spartan conditions. Another building nearby was rented for families and a sick room was also set up there.

Ernst Kamm describes his experiences in 2000 in a conversation with David Bernet. Whether he could still remember numbers and dates correctly at the age of 92, however, remains an open question.

“In the middle of July 1938, Grüninger got me out of bed after a night shift and said: ‘You, Kamm, you have to go to Diepoldsau. We had 1,200 people who defected that night, Jewish refugees. You have to go to Diepoldsau. You must take over this camp. I'll give you four men to help you.’ I had to pack up immediately and he took me personally to Diepoldsau. He said, ‘There's an empty factory belonging to the Frey family, an old embroidery shop that had to be closed because of the bad times.’ No more orders, the war was just around the corner. Our camp in Diepoldsau was only 500 metres from the border. That's when he said, ‘You have to set up the camp, you're a technician’.”1

The costs for renting and setting up the camp, and even for guarding it by the cantonal police, have to be covered by Jewish Refugee Aid. And this organization is increasingly faced with the problem of collecting donations for the relief of a need that one hardly dares to talk about publicly. For fear of xenophobic reactions from the Swiss public. In the camp's common room, however, a large mural is emblazoned with the motto “Thanks to the Swiss people!”

Kamm, who is given command of the camp, is considered quite strict and authoritarian among the refugees. He himself recalls his conflicts of conscience.

“Yes, I was always in a very difficult position. Because I was in favor of helping and I shouldn't have been. Helping against the will of the law – that's a difficult position. In any case, where the husband and the son are already there and the wife is just coming, to finally solve that for the reception. You can't really imagine such a decision. To separate a family that has done nothing wrong. They haven't done anything wrong. They were persecuted. They fled from death, from the life that was to be taken from them.”

And he remembers the diversity in the camp:

“Among the emigrants who came, there were people from all walks of life. From the poor to people with good professions: Lawyers, dentists, doctors or film actors. Then came another saddler, a car mechanic, down to the unskilled worker, like us. The behavior of these people was very different. There were very helpful people. There were many who only did what they had to. At the most, they put their camp in order. Some were just waiting to leave.”

One of the many who sought shelter here was David Selig Scheer. Originally from Poland, he grew up in a Viennese orphanage and had kept his head above water as a construction worker. The other camp inmates remember him as a miserable figure. Even the refugee assistance does not like to take care of him. Apparently he was expelled several times, but nevertheless he managed to find admission to the camp in December 1938. A fellow inmate, Kurt Bettelheim remembers:

“Almost at the border there was a restaurant called ‘Alpenblick’, with whose owner we camp inmates had the best contact. Scheer arrived there on Christmas night, and the landlord called the St. Gall congregation and told the people there: ‘If you don't make sure that this man can stay in Switzerland, then I'll make sure that those you attach great importance to can't come either!’”2

Scheer can now indeed stay. And in the summer of 1939, the solidarity of the other internees once again prevents his expulsion. They go on hunger strike. The relationship between the camp inmates and the Jewish community remained conflictual. Some remember the subsequent appearance of the St. Gall community leader and president of the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities, Saly Mayer, in Diepoldsau:

“Gentlemen, I can inform you that there are still some places available in Dachau.”

It is the same Saly Mayer who is behind the scenes collecting money for the refugees and involved in secret rescue operations.

The internees are not allowed to work and support themselves. Some nevertheless find illegal work with people in Diepoldsau, many of whom are quite fond of the refugees.

The camp is closed in September 1939. The war had begun. Most of the refugees are now interned in labor camps.

Recommended reading:

Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998); Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005

[1] Interview by David Bernet with Ernst Kamm in Landquart, March 2000, for the Archimob project (Archives de la Mobilisation en Suisse 1939-1945).

[2] Quoted from: Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998), p. 93-94.

Common room in Diepoldsau camp, March 1939

Common room in Diepoldsau camp, March 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Schawuot in Diepoldsau camp, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

At Diepoldsau camp, 1939

At Diepoldsau camp, 1939

SIG Archiv 2539, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, Zürich