Five women at the Old Rhine> May 7, 1942

21 Paula Hammerschlag, Marie Winter, Paula Korn, Gertrud und Clara Kantorowicz

Caught in the barbed wire. Four out of five Jewish women from Berlin fail at the Old Rhine

Hohenems, May 7, 1942

“While giving her name in the guardroom, she had a glass of water given to her on the pretext that she was unwell. She mixed white pills into the water and drank this liquid before she could be prevented from doing so. After a short time, an unconscious state set in, so that she had to be admitted to hospital.”[1]

Paula Hammerschlag, the woman in the Hohenems guardhouse, had been arrested at the Hohenems border on May 7, 1942, after midnight. Together with four other, older Jewish women from Berlin, she had tried to escape to Switzerland at the Diepoldsau public bath. Escape helper Jakob Spirig tells Austrian television about this in 2002.

“Of course it was very difficult because of the barbed wire and the barriers, but we young boys risked it. Then we were caught in Switzerland and the women too. ... An ill-considered adventure, I would never do that again. They said they were young ladies. So we thought it would be all right. But there was this barbed wire, or as we Swiss called it: 'Spanish horsemen' ... We ordered the women to the country house for 10 o'clock in the evening. Then we went over, even at risk. We dragged the people to the border. ... We got the women across, but the last woman got her skirt caught on the barbed wire, and she had to get loose. Somehow the customs guards heard this and shouted 'Halt, German customs guards! They ran down from the customs office with torches, and the guard further down fired and ran here too. Then we had to leave, of course. Then we had to leave the women and get to safety. But we were arrested by the Swiss police and brought before a military court. The women were also caught and turned back.”[2]

Three of the women knew each other well from the Berlin circle around the poet Stefan George. In addition to Paula Hammerschlag, the sister of the religious philosopher and poet Margarete Susmann, they were the philosopher Gertrud Kantorowicz and her aunt Clara. They had prepared their escape together with a network of friends in Germany and Switzerland. The Diepoldsau escape helper Jakob Spirig and a colleague had been hired for the risky enterprise.

Gertrud Kantorowicz

Marie Winter had also joined the three in Berlin. Her daughter, the actress Ilse Winter, emigrated to Switzerland soon after 1933 - and is now studying economics in Basel. Her professor is also a member of the George circle, which is now scattered throughout Europe. A contact she now tried to use for her mother. And then, shortly before the agreed escape date, a fifth Berlin woman threatened with deportation, Paula Korn, forced herself on the group.

Before their attempted border crossing, the women spent the night in the Hohenems inns Habsburg and Freschen under false names and waited for the right day. The owner of the Habsburg inn is familiar with the escape plan. One of her employees, Isabella Aberer, finally leads the group to the so-called “Landhaus” near the border, where the Swiss escape helpers are waiting. But the enterprise fails. The German border officials are alert. Only Paula Korn manages to escape to Switzerland.

Three days later in the Hohenems hospital, Paula Hammerschlag dies from the overdose of Phanodorm, with which she poisoned herself in the Hohenems guardhouse at the “Gasthaus zur Post”. Marie Winter and Gertrud and Clara Kantorowicz are brought back to Berlin to the police prison. First comes the complete official robbery, which is now formally organized. All assets are signed over to the German Reich. As early as June 1942, Marie Winter is deported to Minsk and murdered in Maly Trostinec. Clara Kantorowicz is put to death in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in February 1943. The last to die was Gertrud Kantorowicz, also in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, a few days before the liberation by the Red Army.

Interview with Isabella Aberer, 1999:

Recommended reading:

The story of Marie Winter, whose escape at the border failed just as much as that of Paula Hammerschlag and Gertrud and Clara Kantorowicz, is described in the following book:

Gabriel Heim, Ich will keine Blaubeertorte, ich will nur raus. Eine Mutterliebe in Briefen. Cologne 2013

Petra Zudrell (ed.), Der abgerissene Dialog. Die intellektuelle Beziehung Gertrud Kantorowicz – Margarete Susman oder Die Schweizer Grenze bei Hohenems als Endpunkt eines Fluchtversuchs, Innsbruck 1999

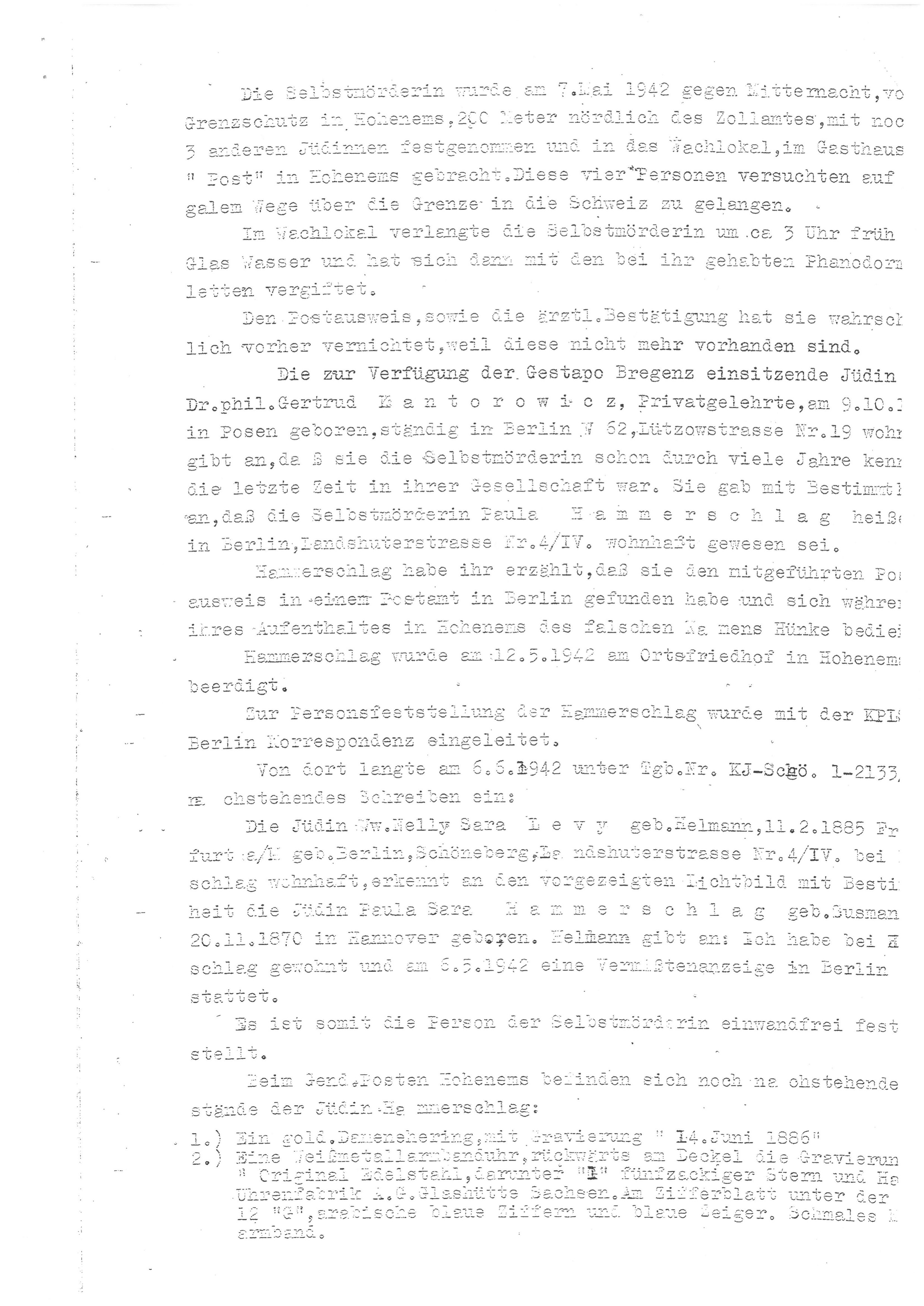

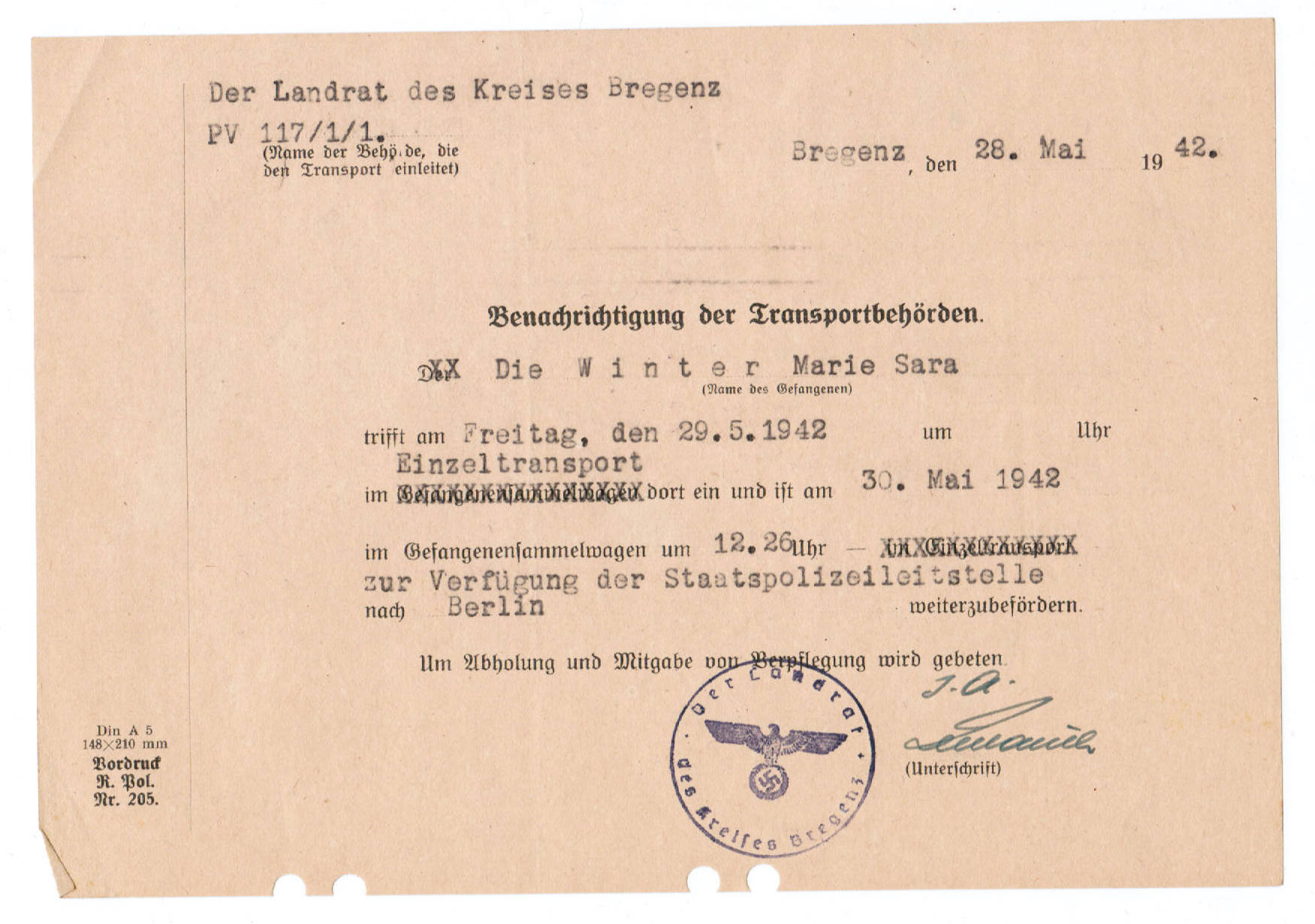

[1] Report of the Hohenems Gendarmerie post of May 12, 1942, quoted after: Bericht der Hohenemser Gendarmerie vom 12.5.1942, quoted after: Angela Rammstedt, "Flucht vor der 'Evakuierung'", in: Petra Zudrell (ed.), Der abgerissene Dialog. Die intellektuelle Beziehung Gertrud Kantorowicz – Margarete Susman oder Die Schweizer Grenze bei Hohenems als Endpunkt eines Fluchtversuchs. Innsbruck 1999, p. 57.

[2] Interview with Jakob Spirig, in: „Heimat, fremde Heimat“ (Markus Barnay, ORF 2002).

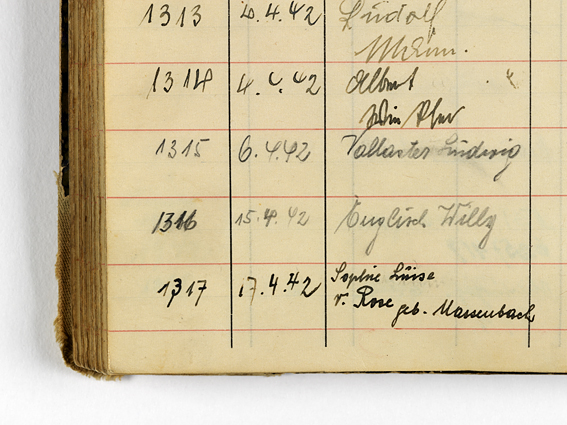

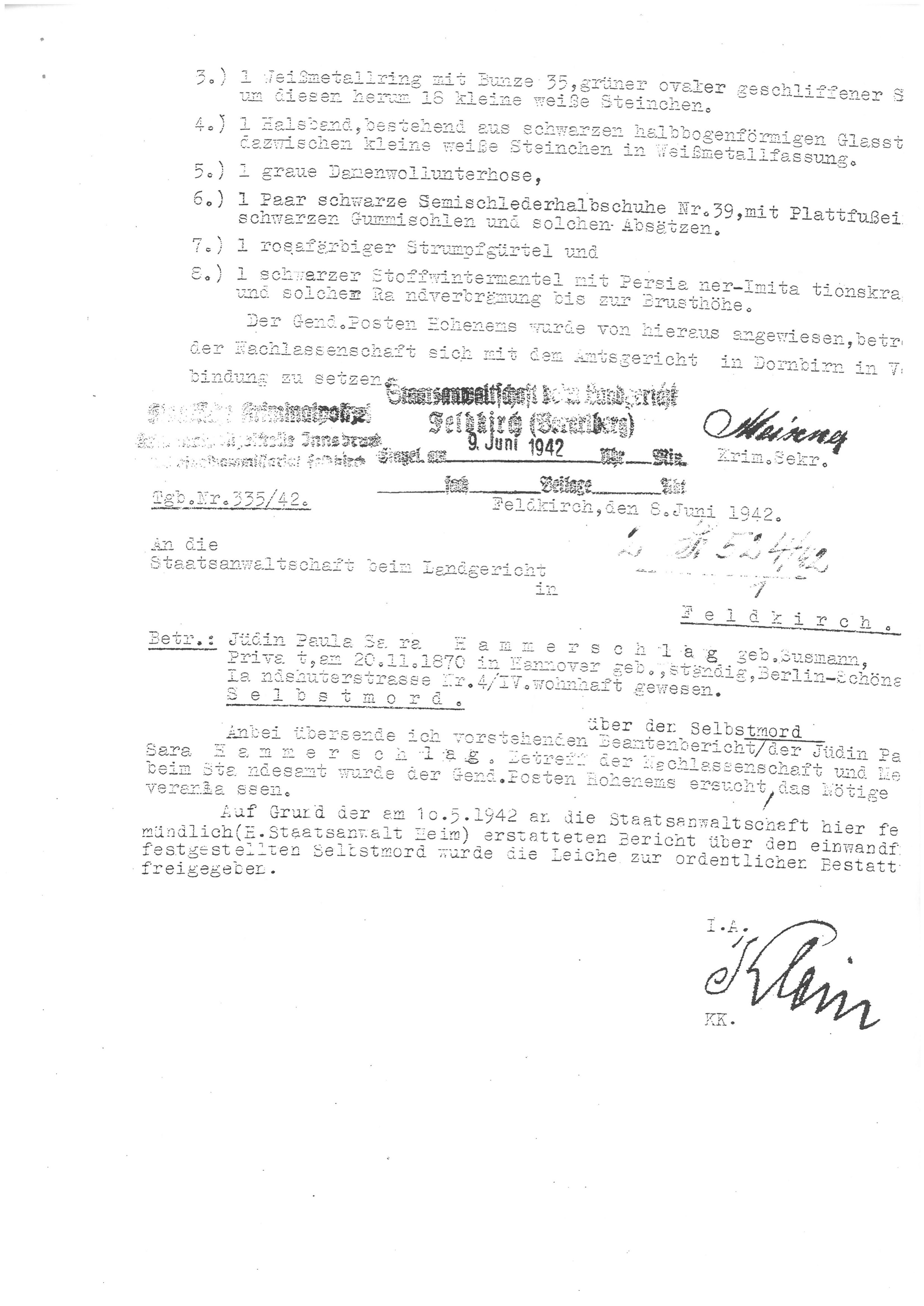

Guestbook of the Hohenems Habsburg Inn. Gertrud Kantorowicz stayed there under the false name Sophie Luise v. Rose.

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Border fence at Diepoldsau bath, 1942

Archiv der Finanzlandesdirektion für Vorarlberg, Feldkirch

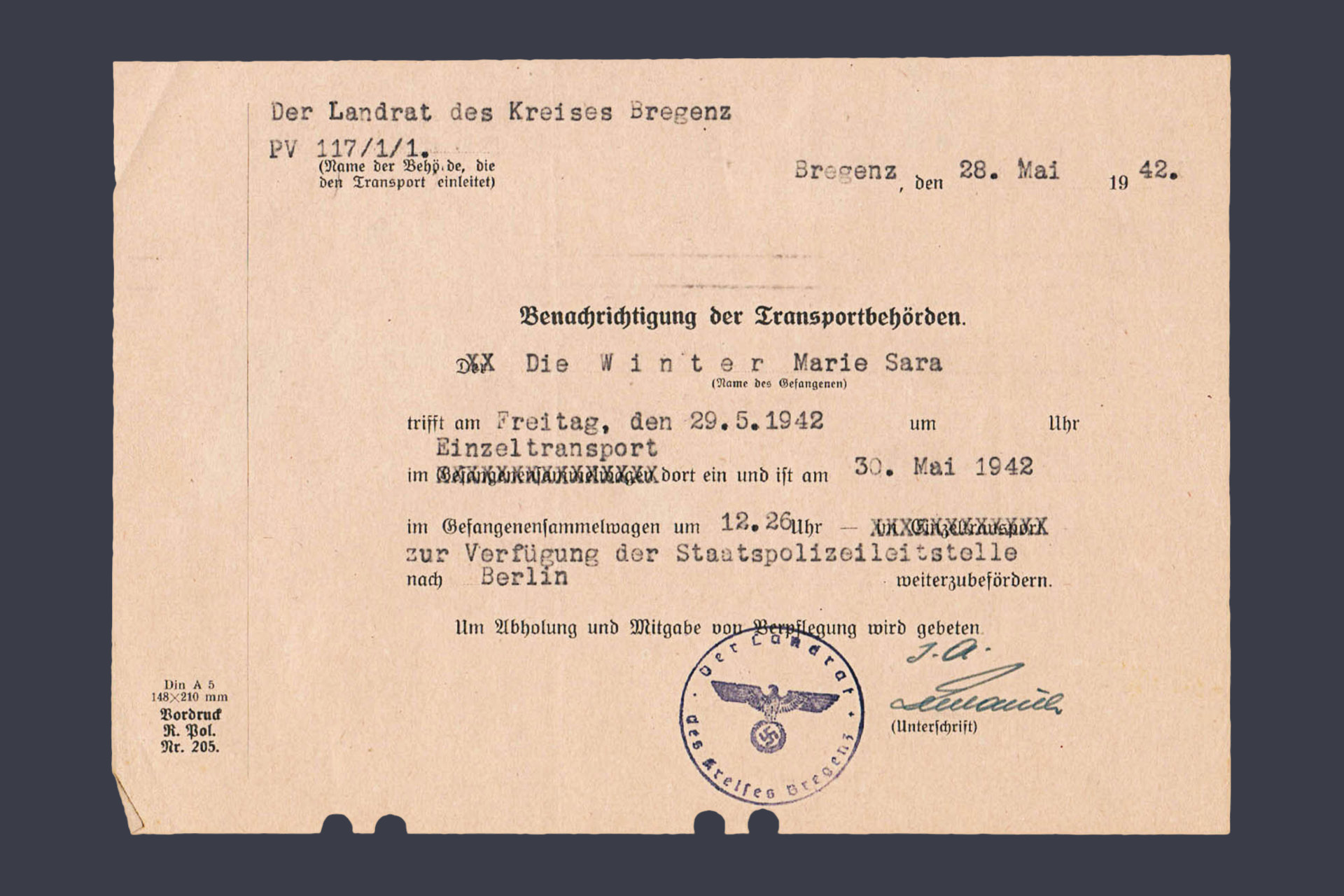

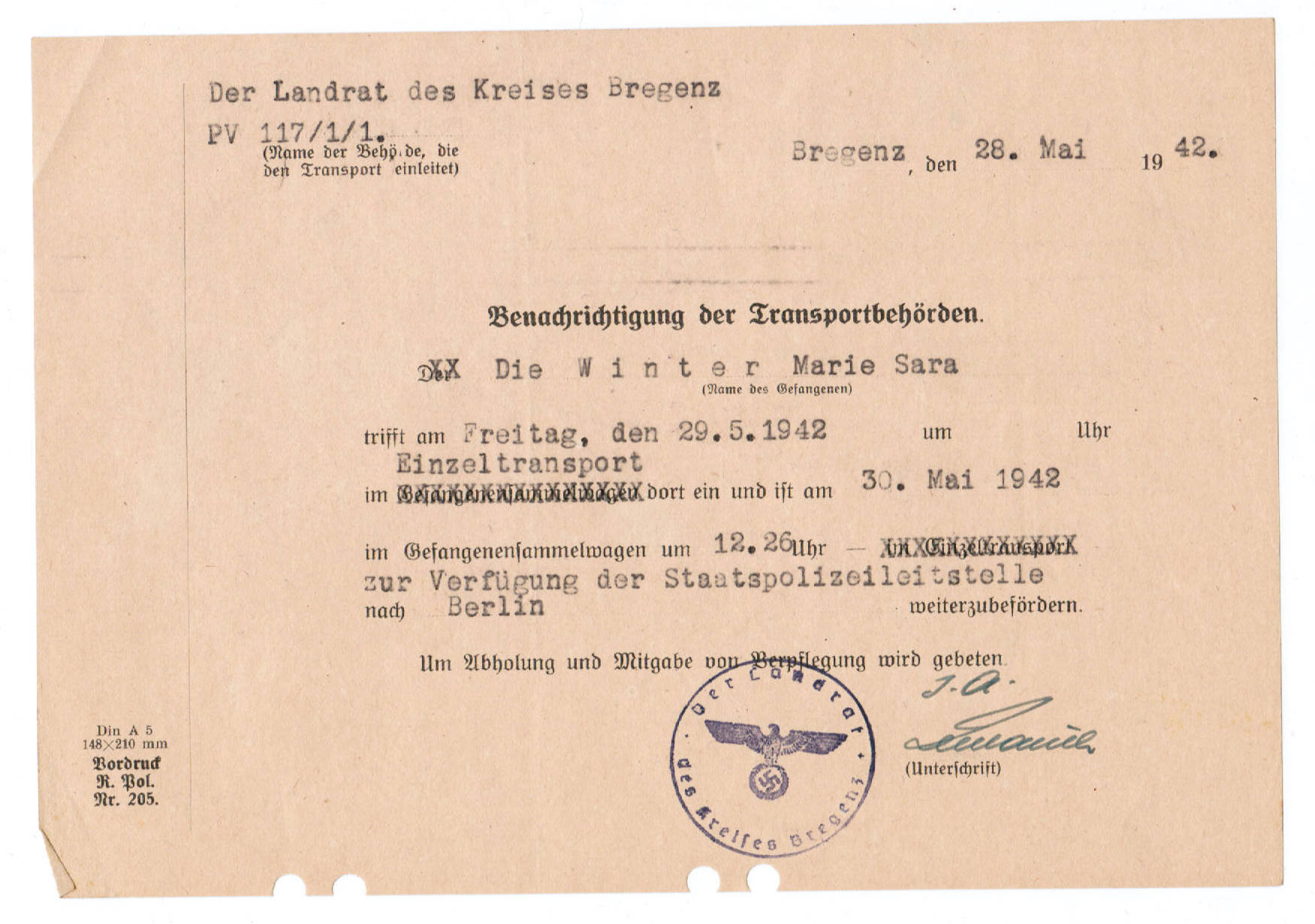

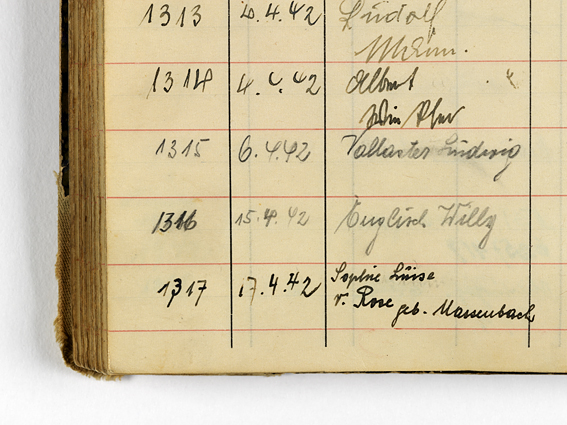

Notification of the transport authorities regarding the "single transport" of Marie Winter to Berlin, May 28, 1942.

Legacy of Ilse Heim-Winter

Hohenems Schlossplatz and Schlossberg, Foto Heim Dornbirn, 1941

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

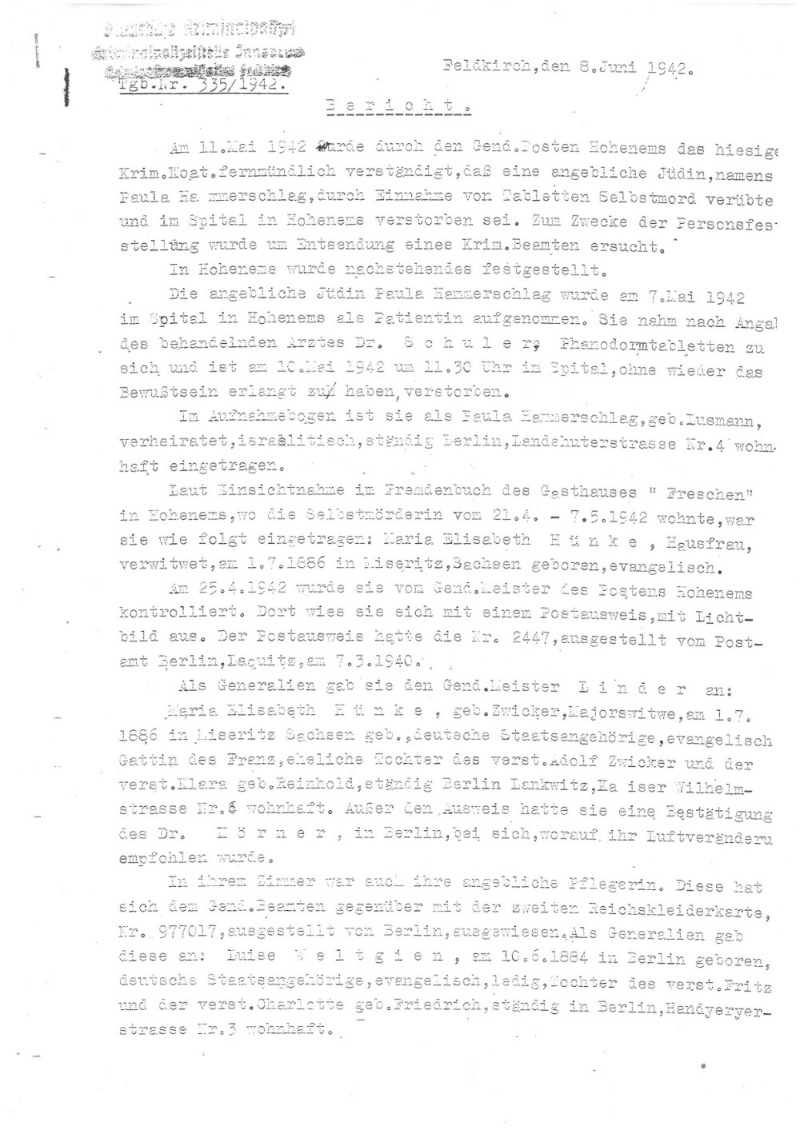

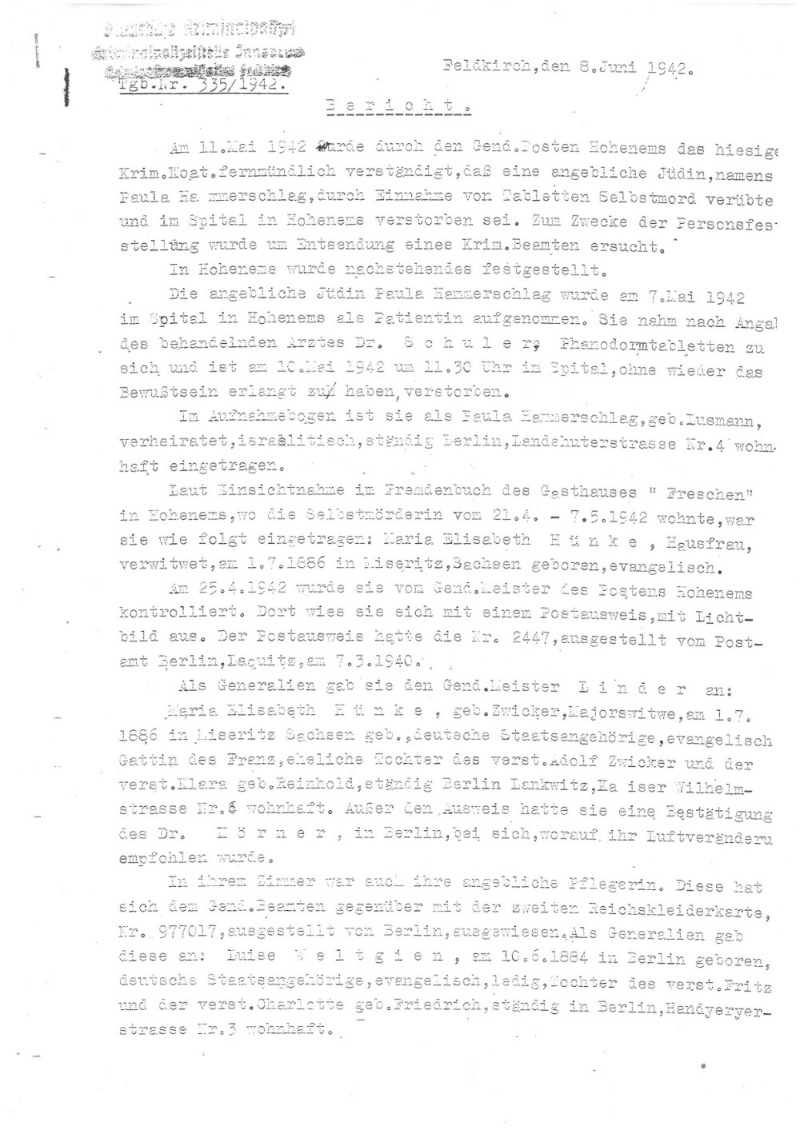

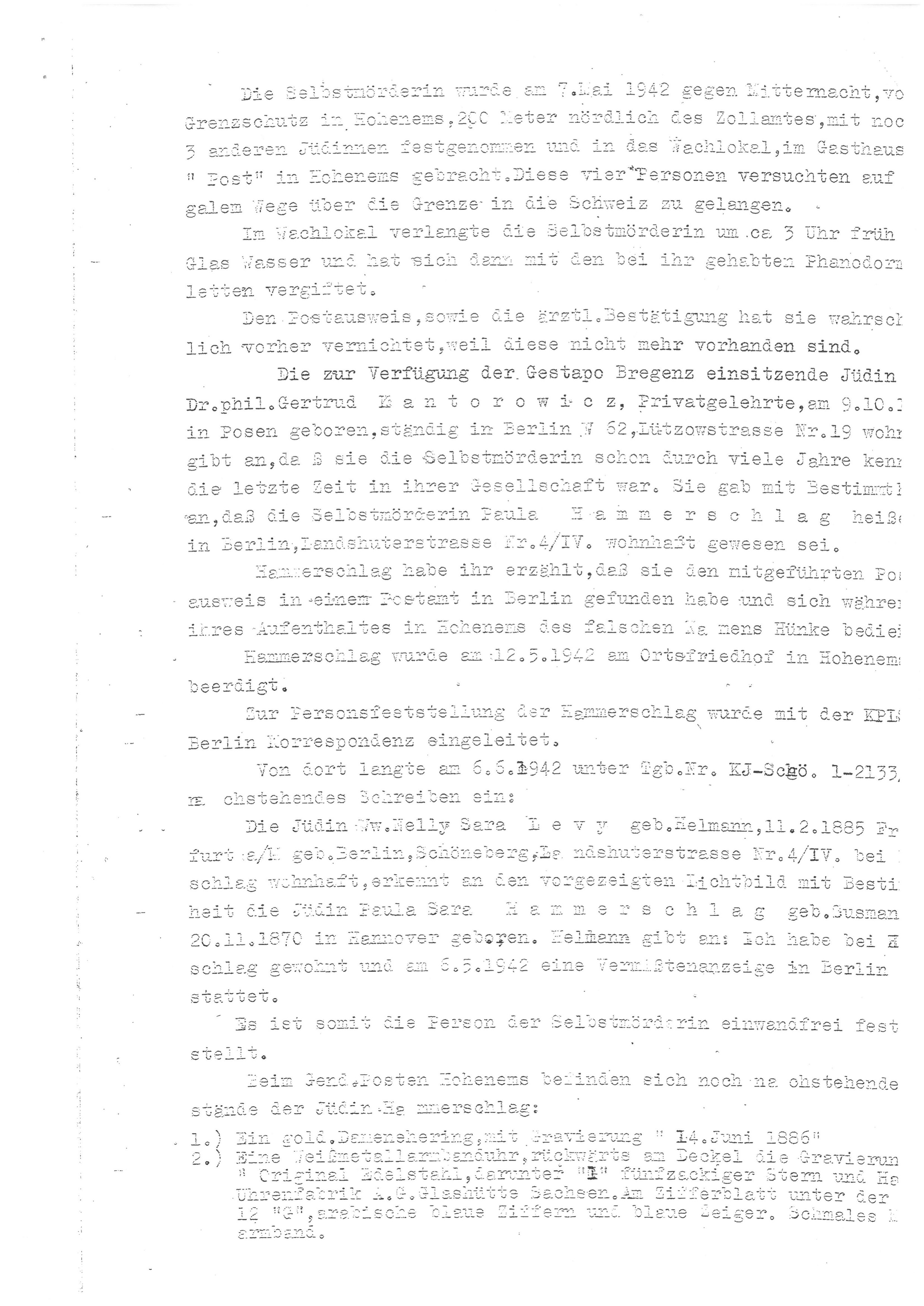

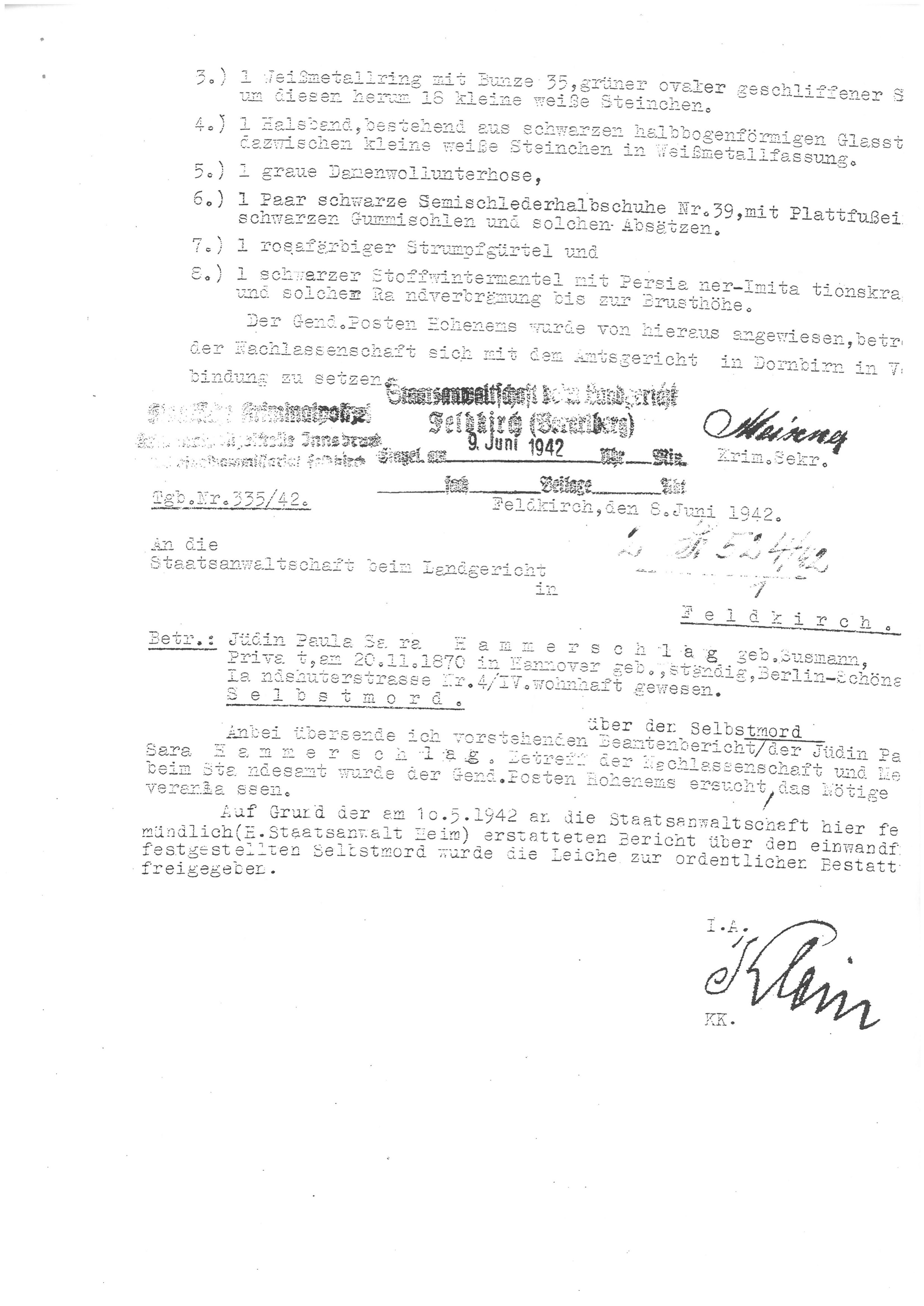

Report of the Feldkirch Criminal Police Division, June 8, 1942

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

21 Paula Hammerschlag, Marie Winter, Paula Korn, Gertrud und Clara Kantorowicz

Caught in the barbed wire. Four out of five Jewish women from Berlin fail at the Old Rhine

Hohenems, May 7, 1942

“While giving her name in the guardroom, she had a glass of water given to her on the pretext that she was unwell. She mixed white pills into the water and drank this liquid before she could be prevented from doing so. After a short time, an unconscious state set in, so that she had to be admitted to hospital.”[1]

Paula Hammerschlag, the woman in the Hohenems guardhouse, had been arrested at the Hohenems border on May 7, 1942, after midnight. Together with four other, older Jewish women from Berlin, she had tried to escape to Switzerland at the Diepoldsau public bath. Escape helper Jakob Spirig tells Austrian television about this in 2002.

“Of course it was very difficult because of the barbed wire and the barriers, but we young boys risked it. Then we were caught in Switzerland and the women too. ... An ill-considered adventure, I would never do that again. They said they were young ladies. So we thought it would be all right. But there was this barbed wire, or as we Swiss called it: 'Spanish horsemen' ... We ordered the women to the country house for 10 o'clock in the evening. Then we went over, even at risk. We dragged the people to the border. ... We got the women across, but the last woman got her skirt caught on the barbed wire, and she had to get loose. Somehow the customs guards heard this and shouted 'Halt, German customs guards! They ran down from the customs office with torches, and the guard further down fired and ran here too. Then we had to leave, of course. Then we had to leave the women and get to safety. But we were arrested by the Swiss police and brought before a military court. The women were also caught and turned back.”[2]

Three of the women knew each other well from the Berlin circle around the poet Stefan George. In addition to Paula Hammerschlag, the sister of the religious philosopher and poet Margarete Susmann, they were the philosopher Gertrud Kantorowicz and her aunt Clara. They had prepared their escape together with a network of friends in Germany and Switzerland. The Diepoldsau escape helper Jakob Spirig and a colleague had been hired for the risky enterprise.

Gertrud Kantorowicz

Marie Winter had also joined the three in Berlin. Her daughter, the actress Ilse Winter, emigrated to Switzerland soon after 1933 - and is now studying economics in Basel. Her professor is also a member of the George circle, which is now scattered throughout Europe. A contact she now tried to use for her mother. And then, shortly before the agreed escape date, a fifth Berlin woman threatened with deportation, Paula Korn, forced herself on the group.

Before their attempted border crossing, the women spent the night in the Hohenems inns Habsburg and Freschen under false names and waited for the right day. The owner of the Habsburg inn is familiar with the escape plan. One of her employees, Isabella Aberer, finally leads the group to the so-called “Landhaus” near the border, where the Swiss escape helpers are waiting. But the enterprise fails. The German border officials are alert. Only Paula Korn manages to escape to Switzerland.

Three days later in the Hohenems hospital, Paula Hammerschlag dies from the overdose of Phanodorm, with which she poisoned herself in the Hohenems guardhouse at the “Gasthaus zur Post”. Marie Winter and Gertrud and Clara Kantorowicz are brought back to Berlin to the police prison. First comes the complete official robbery, which is now formally organized. All assets are signed over to the German Reich. As early as June 1942, Marie Winter is deported to Minsk and murdered in Maly Trostinec. Clara Kantorowicz is put to death in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in February 1943. The last to die was Gertrud Kantorowicz, also in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, a few days before the liberation by the Red Army.

Interview with Isabella Aberer, 1999:

Recommended reading:

The story of Marie Winter, whose escape at the border failed just as much as that of Paula Hammerschlag and Gertrud and Clara Kantorowicz, is described in the following book:

Gabriel Heim, Ich will keine Blaubeertorte, ich will nur raus. Eine Mutterliebe in Briefen. Cologne 2013

Petra Zudrell (ed.), Der abgerissene Dialog. Die intellektuelle Beziehung Gertrud Kantorowicz – Margarete Susman oder Die Schweizer Grenze bei Hohenems als Endpunkt eines Fluchtversuchs, Innsbruck 1999

[1] Report of the Hohenems Gendarmerie post of May 12, 1942, quoted after: Bericht der Hohenemser Gendarmerie vom 12.5.1942, quoted after: Angela Rammstedt, "Flucht vor der 'Evakuierung'", in: Petra Zudrell (ed.), Der abgerissene Dialog. Die intellektuelle Beziehung Gertrud Kantorowicz – Margarete Susman oder Die Schweizer Grenze bei Hohenems als Endpunkt eines Fluchtversuchs. Innsbruck 1999, p. 57.

[2] Interview with Jakob Spirig, in: „Heimat, fremde Heimat“ (Markus Barnay, ORF 2002).

Guestbook of the Hohenems Habsburg Inn. Gertrud Kantorowicz stayed there under the false name Sophie Luise v. Rose.

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Border fence at Diepoldsau bath, 1942

Archiv der Finanzlandesdirektion für Vorarlberg, Feldkirch

Notification of the transport authorities regarding the "single transport" of Marie Winter to Berlin, May 28, 1942.

Legacy of Ilse Heim-Winter

Hohenems Schlossplatz and Schlossberg, Foto Heim Dornbirn, 1941

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Report of the Feldkirch Criminal Police Division, June 8, 1942

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems