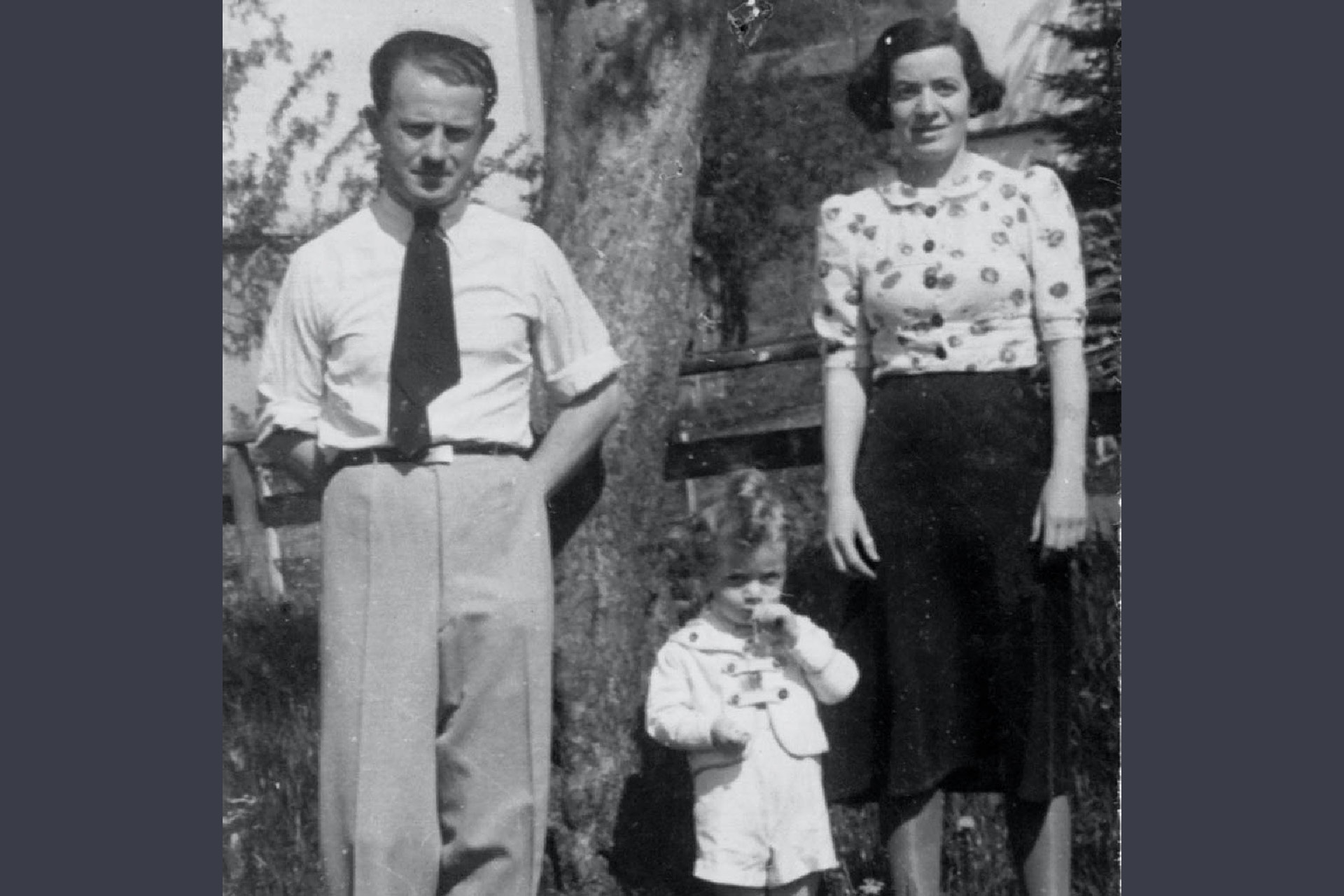

Family Kreutner> November 1938

22 Kreutner Family

“Such things remain in memory”. Beaten up in Vienna and turned back several times at the

border. The escape of the Kreutner family

Hohenems – Diepoldsau, November 1938

“Due to blood loss, I started feeling dizzy. I collapsed, unconscious, half unconscious. My wife was inside the house, and the boy screamed since he had terrible earaches. … And I collapsed and can still remember, half-dazed, as someone was saying: ‘Come on, let’s give him another… .’ —I say this precisely the way I remember—'We could give him another kick in the gut with the boot!’ Then one of them said: ‘No need for this. He’s no longer uttering a peep anymore.’ I’d say this was good luck. They left me alone, unconscious on the ground and bleeding, and vanished. Thinking that nothing could be done with this one anymore, impossible to take him along. … And, ultimately, this taking along would mean concentration camp. Whether I’d still be alive today, I don’t know, but I doubt it. Then they left, and my wife came out with the boy—the boy, barely a year and a half, in her arms.”[1]

In 1997, Jakob Kreutner tells Swiss Television how Nazi thugs had maltreated him on the “Night of Broken Glass” in Vienna. Shortly after the attack, the family decided to flee to Switzerland. Several times they were turned away at the border and tried again and again.

“Such things stick in one’s memory. It was snowing, the Rhine in flood, and we had to step on rocks. I don’t know, were these smuggling paths? And suddenly the boy together with the guide—he had taken the boy since the boy had screamed—slipped and then all hell broke loose. He screamed so much that it was definitely audible—ironically speaking—all the way to St. Gall. And then he says: ‘You have to go up here!’ There is a hill like almost everywhere along the border or let’s say: an embankment, and he says: ‘Go, it’s up to you now.’ And disappears. I want to stress, the man who guided us was an Austrian. From Lustenau … . No, Hohenems. And he was gone. And then we went up, and the border guards were there, the Swiss border guards with capes, their weapons at the ready. Obviously, they had their instructions. And so they asked my wife—she hasn’t mentioned this in all the excitement—they asked her: ‘Where are you going?’ Then my wife replied: ‘If you send me back, then you better shoot us right here.’

Finally, a border guard takes the family with him. It is Alfons Eigenmann, whose wife insists on taking care of the drenched people. Eigenmann himself publicizes the case in a letter that appears anonymously in Swiss newspapers. For a long time to come, the family has to fight to be allowed to stay in Switzerland. In 1948, the aliens police tell them that they could immigrate to the newly founded state of Israel. But the Kreutners stay – and become Swiss.

[1] Interview with Jakob and Ida Kreutner, in: „Die Fluchthelfer von Diepoldsau“ (Hansjürg Zumstein, Swiss Television SRF, 1997)

Border guards between the Hohenems bath and the Hohenems customs office, August 1943

Archiv der Finanzlandesdirektion für Vorarlberg, Feldkirch

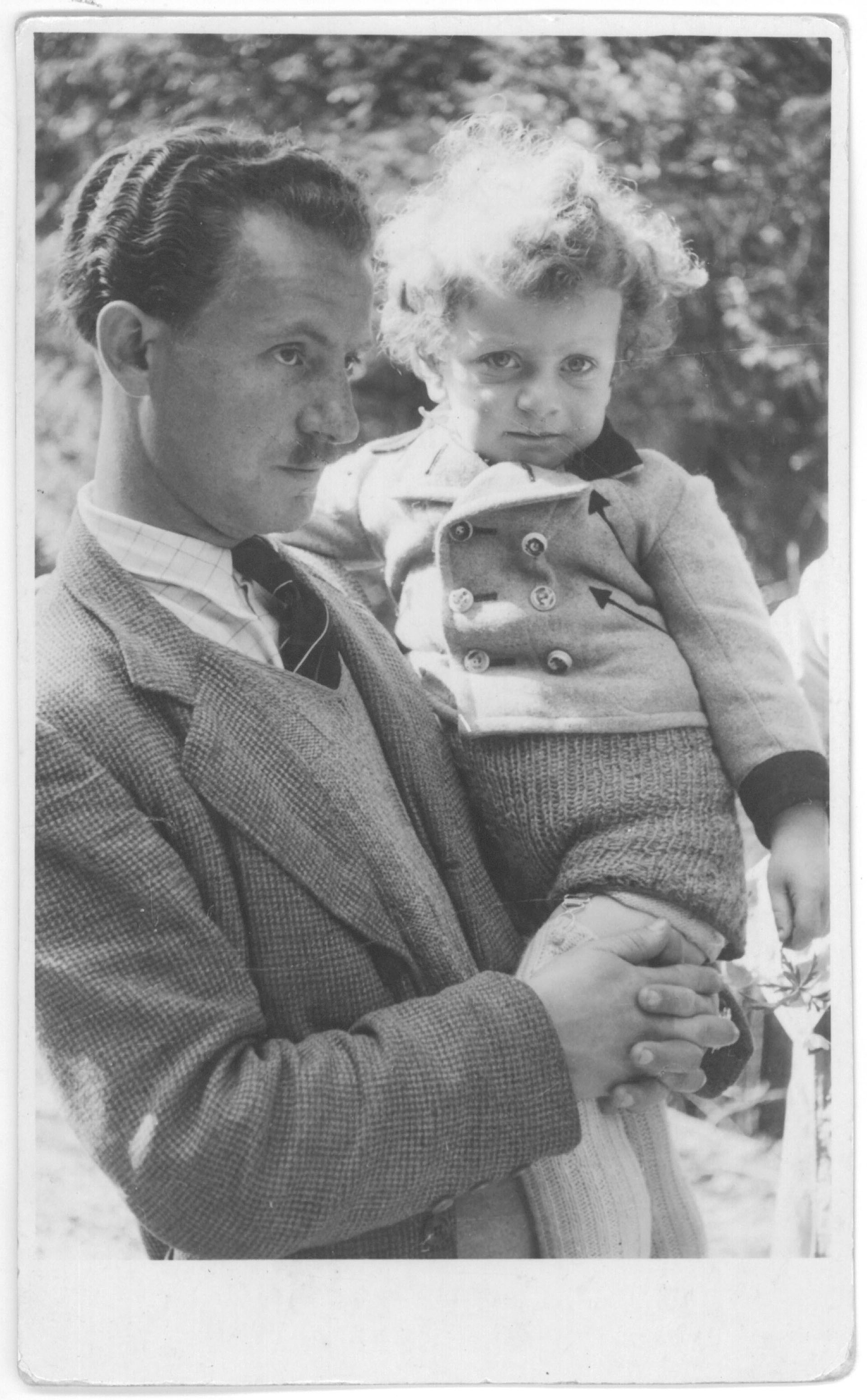

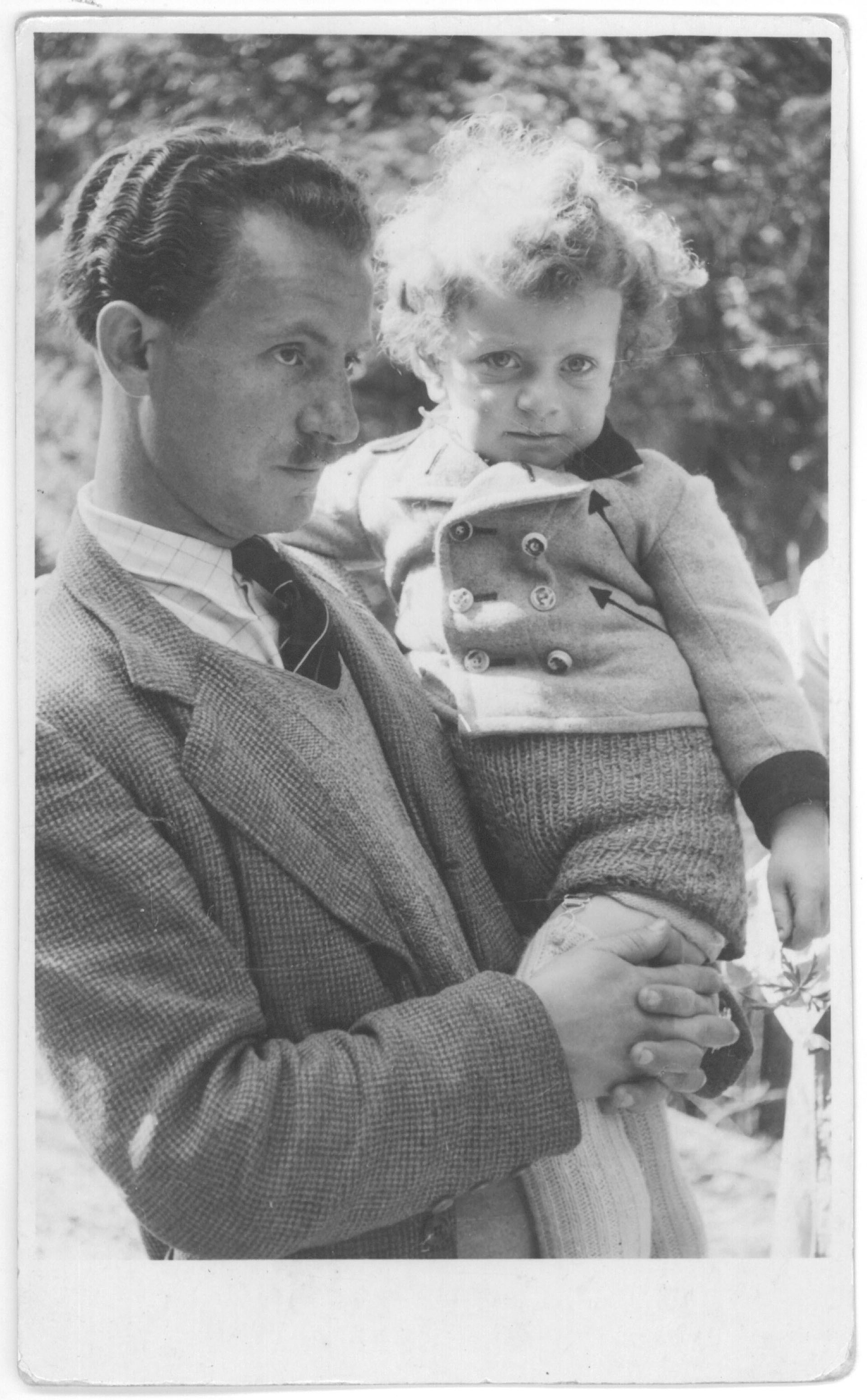

Jakob Kreutner with his son Robert, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Ida Kreutner in Vienna, before 1938

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

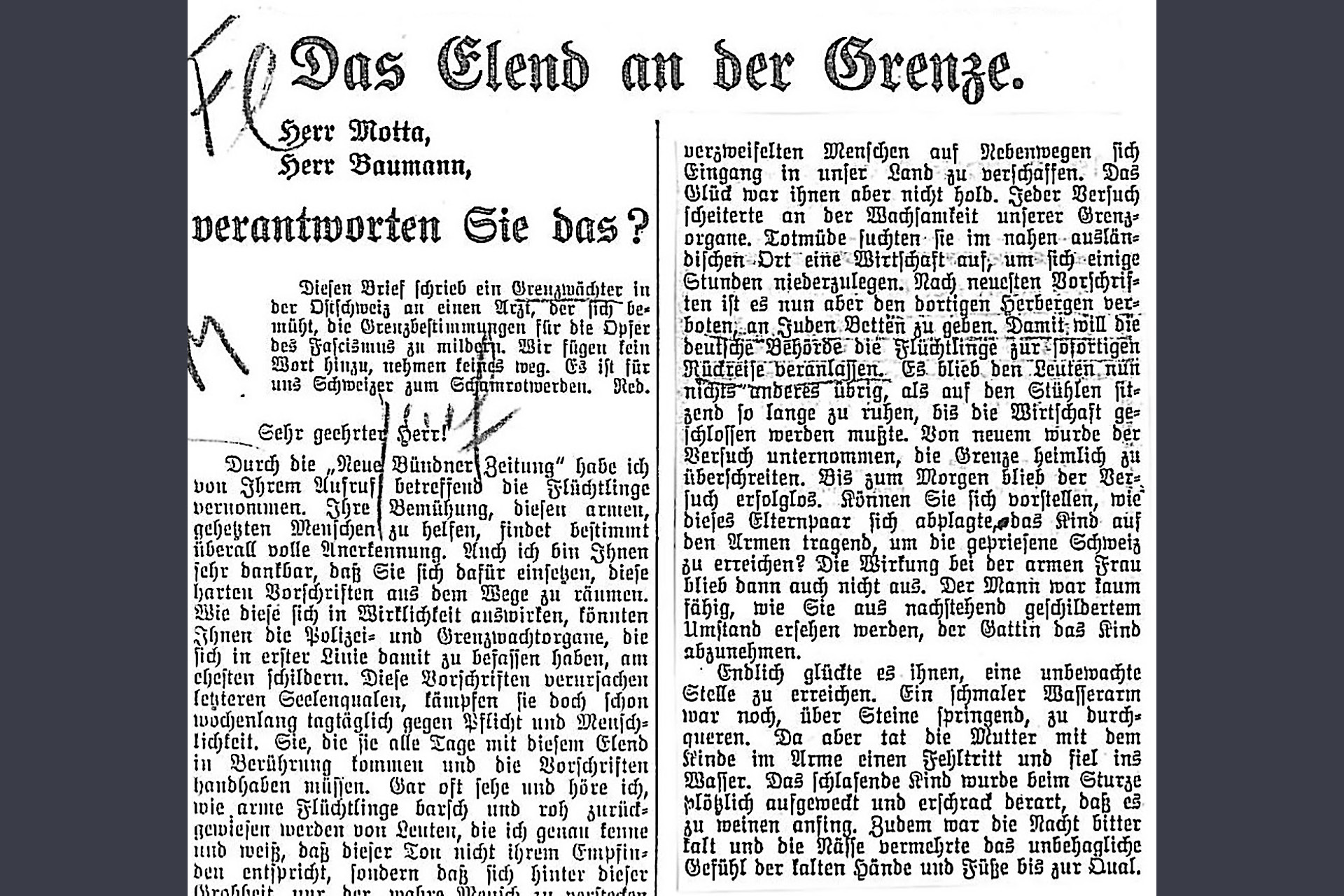

Anonymously published letter by Alfons Eigenmann, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

22 Kreutner Family

“Such things remain in memory”. Beaten up in Vienna and turned back several times at the

border. The escape of the Kreutner family

Hohenems – Diepoldsau, November 1938

“Due to blood loss, I started feeling dizzy. I collapsed, unconscious, half unconscious. My wife was inside the house, and the boy screamed since he had terrible earaches. … And I collapsed and can still remember, half-dazed, as someone was saying: ‘Come on, let’s give him another… .’ —I say this precisely the way I remember—'We could give him another kick in the gut with the boot!’ Then one of them said: ‘No need for this. He’s no longer uttering a peep anymore.’ I’d say this was good luck. They left me alone, unconscious on the ground and bleeding, and vanished. Thinking that nothing could be done with this one anymore, impossible to take him along. … And, ultimately, this taking along would mean concentration camp. Whether I’d still be alive today, I don’t know, but I doubt it. Then they left, and my wife came out with the boy—the boy, barely a year and a half, in her arms.”[1]

In 1997, Jakob Kreutner tells Swiss Television how Nazi thugs had maltreated him on the “Night of Broken Glass” in Vienna. Shortly after the attack, the family decided to flee to Switzerland. Several times they were turned away at the border and tried again and again.

“Such things stick in one’s memory. It was snowing, the Rhine in flood, and we had to step on rocks. I don’t know, were these smuggling paths? And suddenly the boy together with the guide—he had taken the boy since the boy had screamed—slipped and then all hell broke loose. He screamed so much that it was definitely audible—ironically speaking—all the way to St. Gall. And then he says: ‘You have to go up here!’ There is a hill like almost everywhere along the border or let’s say: an embankment, and he says: ‘Go, it’s up to you now.’ And disappears. I want to stress, the man who guided us was an Austrian. From Lustenau … . No, Hohenems. And he was gone. And then we went up, and the border guards were there, the Swiss border guards with capes, their weapons at the ready. Obviously, they had their instructions. And so they asked my wife—she hasn’t mentioned this in all the excitement—they asked her: ‘Where are you going?’ Then my wife replied: ‘If you send me back, then you better shoot us right here.’

Finally, a border guard takes the family with him. It is Alfons Eigenmann, whose wife insists on taking care of the drenched people. Eigenmann himself publicizes the case in a letter that appears anonymously in Swiss newspapers. For a long time to come, the family has to fight to be allowed to stay in Switzerland. In 1948, the aliens police tell them that they could immigrate to the newly founded state of Israel. But the Kreutners stay – and become Swiss.

[1] Interview with Jakob and Ida Kreutner, in: „Die Fluchthelfer von Diepoldsau“ (Hansjürg Zumstein, Swiss Television SRF, 1997)

Border guards between the Hohenems bath and the Hohenems customs office, August 1943

Archiv der Finanzlandesdirektion für Vorarlberg, Feldkirch

Jakob Kreutner with his son Robert, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Ida Kreutner in Vienna, before 1938

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems