Paul Grüninger> August 17, 1938

23 Paul Grüninger

“Can't we close our borders better?” Paul Grüninger and Swiss refugee policy

Bern, August 17, 1938

On August 17, 1938 Heinrich Rothmund, head of the immigration police in the Federal Department of Justice and Police, invites the cantonal police directors to room 86 of the parliament building in Bern. The extraordinary conference is to discuss the situation at the border and how to deal with the growing number of refugees trying to enter Switzerland from the German Reich. One of the participants is the captain of the St. Gall cantonal police, Paul Grüninger.

Rothmund opens the conference with a report that makes the situation seem dramatic. Far more than 1000 illegal refugees were in Switzerland. And the German Reich would now also distribute German passports to all Austrians. One would have to think about extending the visa requirement for Austrians to all Germans. The Zurich police director Robert Briner, who is also president of the Swiss Central Office for Refugee Aid, provides the cue Rothmund was expecting:

“Can't we close our borders better? Removing refugees is more difficult than keeping them away.”

St. Gall councillor Valentin Keel speaks of the “cultural shame of the persecution of the Jews” in Germany, a remark that is not recorded in the minutes. Thurgau police chief Ernst Haudenschild has the following response:

“The greatest punishment for the German authorities is the deportation of all refugees. Today we are dealing with the Jews, in a few months probably other refugees from Germany. Our cantonal government has given us strict instructions to turn away all refugees. We have no political refugees and no Jewish refugees in our canton. You may order and decide what you like in Bern, our canton will not admit any refugees.”

It is Paul Grüninger who dares to openly object:

“The previous speaker's comments are surprising. The expulsion of the refugees is not possible, if only for reasons of humanity. We have to let many in. We have an interest in keeping these people together as much as possible so that controls can be carried out and also for hygienic reasons. If we turn people away, they will come in uncontrollably. Complete closure of the border is not possible.”1

Support for Grüninger comes above all from the representative of Graubünden, Department Secretary Dr. Bühler. The social democratic representatives from Basel and Schaffhausen, police director Brechbühl and councillor Bührer, also speak out – for the time being – against ruthless deportations and refoulement. The others, in line with Rothmund, demand the immediate closure of the borders.

In the following press release, there is no more mention of the dissenting opinions. The decision to close the border to refugees was unanimous. Two days later, the police directors are informed,

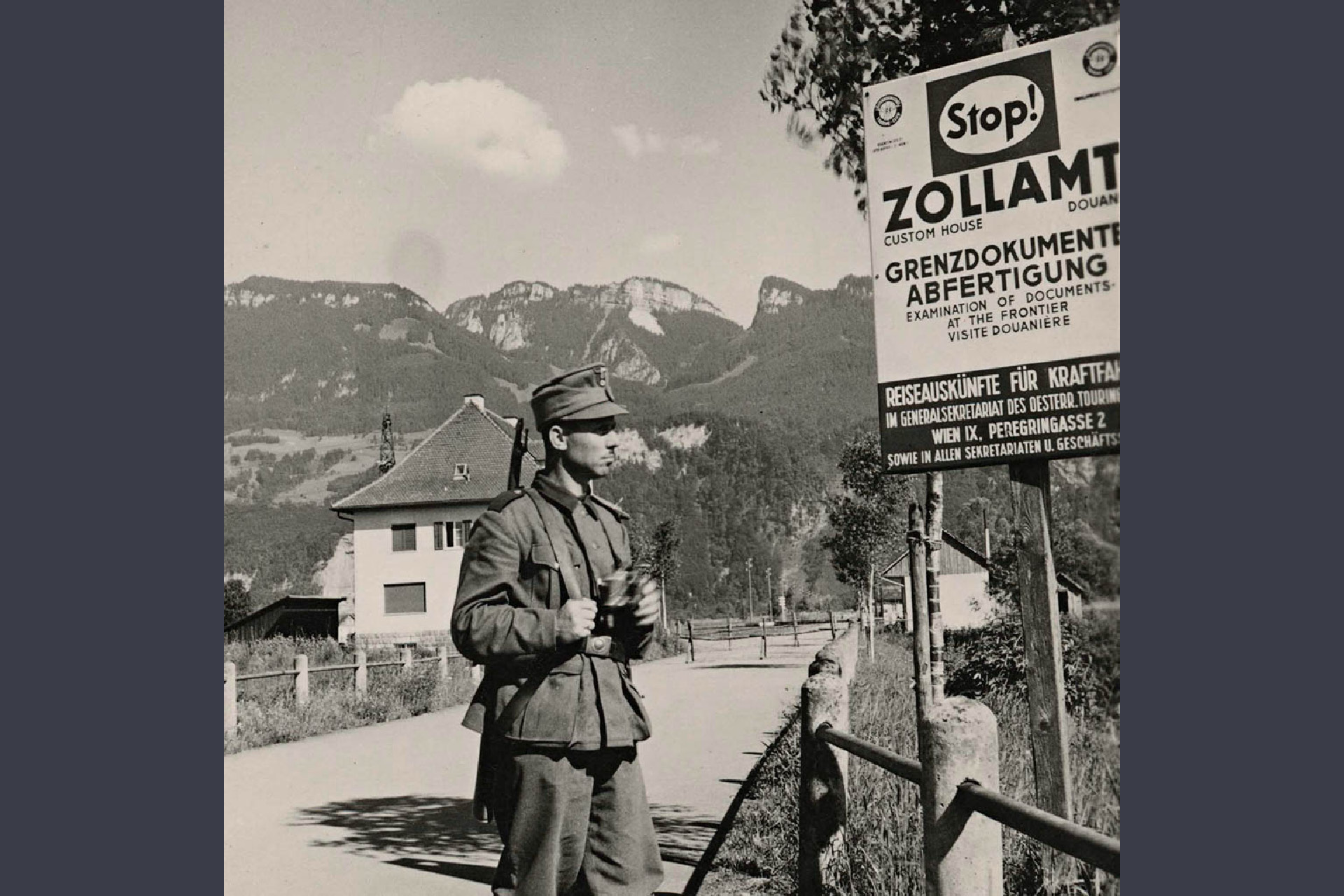

“that a further influx of illegal refugees cannot be tolerated. (...) Since the eastern border is difficult to protect, especially near Diepoldsau, the border control there was reinforced from the stocks of the volunteer border guard companies.”

Paul Grüninger, who openly spoke out against the border closure in the conference, had already been in conflict with the orders from Bern for weeks at this point.2

Born in St. Gall in 1891, Grüninger had initially pursued a career as a primary school teacher. And as a passionate footballer, he had won the Swiss championship in 1915 with his team, the St. Gall club SC Brühl, as a left winger. In 1919, Grüninger switched to the police service, where he was promoted to commander of the St. Gall cantonal police in 1925. And becomes president of his football club.

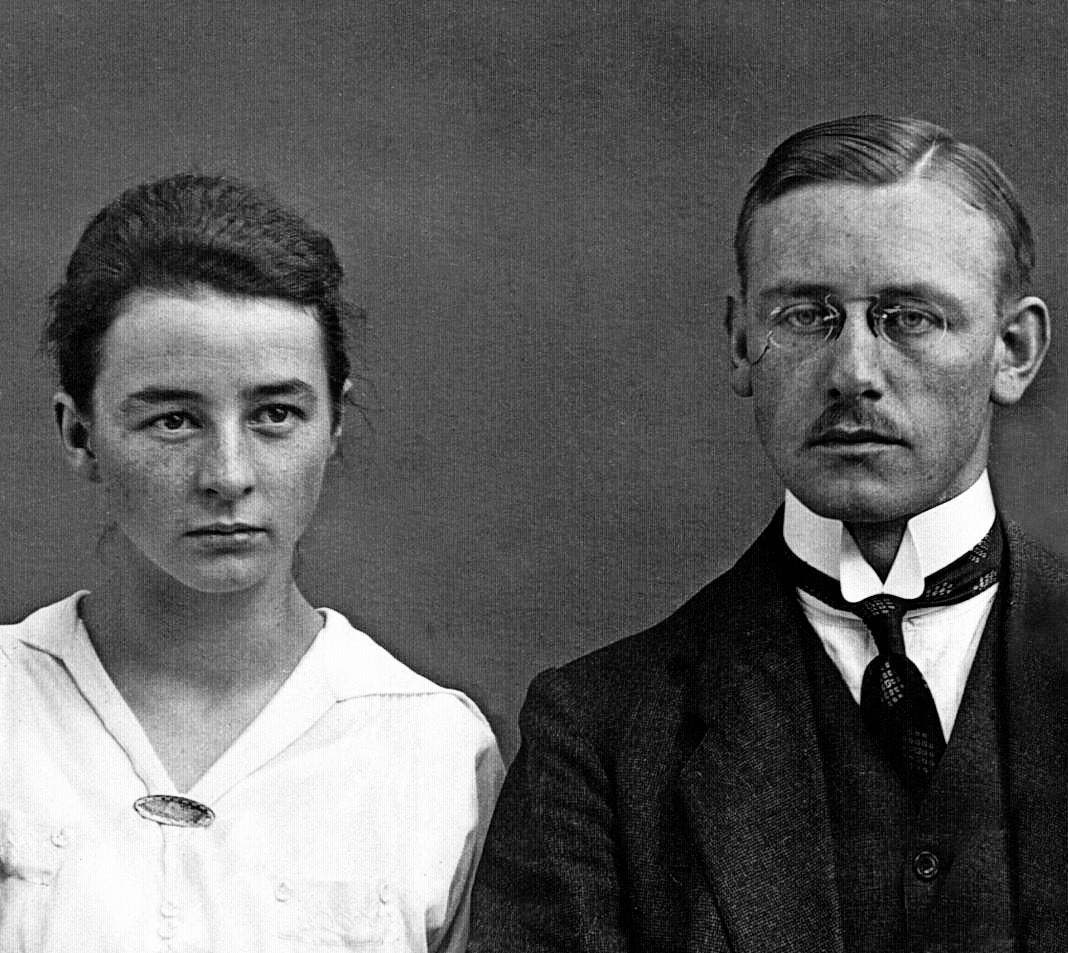

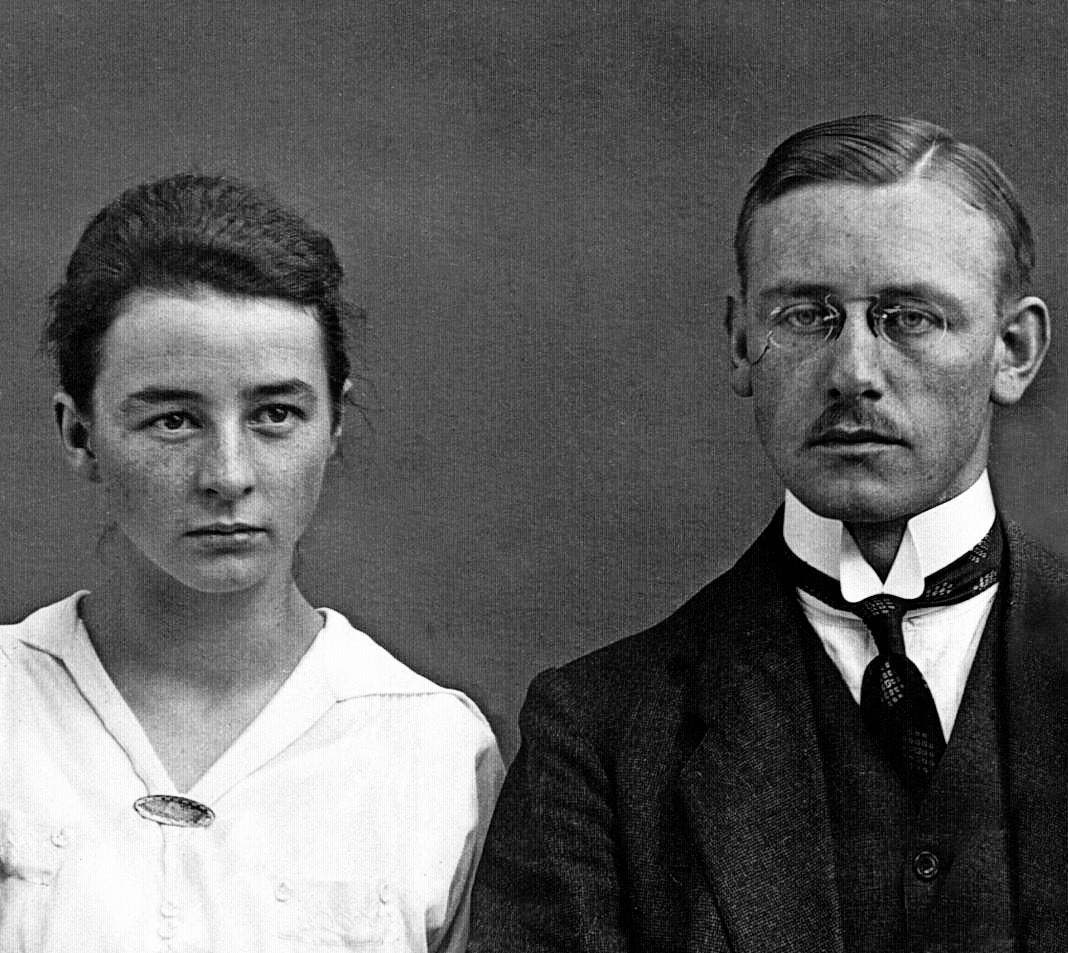

Wedding photo of Alice and Paul Grüninger, 1921

In 1938, Grüninger is confronted with the plight of the refugees. At first he reacted indecisively, then he obeyed his compassion more and more. Again and again, refugees who had managed to cross the border illegally came to his office in St. Gall and asked for a residence permit; more and more often he was called to the border himself to decide on the spot. And most of the time he decides in favor of the refugees. The Israelite Refugee Aid under Sidney Dreyfus sets up its own office in St. Gall. At the beginning of August, the refugee quarters in private accommodation and boarding houses are no longer sufficient. Grüninger sets up a refugee camp in an empty embroidery shop in Diepoldsau. The costs for this have to be covered by the Israelite Refugee Aid as the organization is otherwise responsible for the care of the refugees. Eventually Grüninger also begins to smuggle valuables across the border for the refugees.

With the closing of the border on August 18 and the order to admit no one, Grüninger and Dreyfus are left only with the choice of backdating the arrival of those people who still manage to cross the border afterwards. It is these life-saving “breaches of official duty” and “falsification of documents” for which Paul Grüninger is soon dismissed and put on trial.

Representatives of Switzerland, on the other hand, negotiate with the Germans about the visa requirement demanded by Rothmund. The German side proposes marking the passports of Jews and demands that Switzerland do the same.

A general marking of Jewish Swiss citizens is out of the question for Rothmund. As far as the refugees are concerned, he admittedly prefers another solution, not so offensive in the eyes of world public opinion, but just as effective: his own checks on who is Jewish and who is not. Four weeks after the conference, on September 15, 1938, he reports to the Federal Department of Justice and Police:

“We have succeeded to date in preventing the Judaization of Switzerland through systematic and careful work. (...) If we have the visa, Germany is completely free to give the emigrants papers as it wishes and does not need to designate them as such. We would find them out among those who would not be able to produce an Aryan identity card, a membership book of the Party, the German Labor Front (...) etc. (...) At the border we would have a clean order.”3

The German side, of course, does not want to accept a general visa requirement for all Reich citizens. So they finally agree on the J-stamp in the passports of German Jews. The stigmatization becomes official. In January, Rothmund writes with satisfaction to the Swiss envoy in The Hague, Arthur-Edouard de Pury:

“We have not fought for twenty years with the means of the immigration police against the increase of foreign infiltration and especially against the Judaization of Switzerland, in order to have emigrants forced upon us today.“4

At the beginning of 1939, pressure grows on Grüninger, as well as on government councillor Keel, who must fear for his re-election. Rothmund demands an investigation into the “irregularities” in the canton of St. Gall that have come to his attention. And the right wing nationalist “Vaterländische Verband” threatens to make public the “scandal” of illegal entries. On April 3, 1939, Grüninger was suspended, and finally dishonorably dismissed with the deprivation of his pension rights. In 1940, he was sentenced to a fine.

Grüninger is without means. The Jewish community does not dare to support him openly. Refugee aid as a whole is now threatened. The textile industrialist Elias Sternbuch, Recha Sternbuch's brother-in-law, finally gives him a job selling raincoats in Basle. But Grüninger is no good as a businessman. After unsuccessful attempts as a sales representative, he becomes a primary school teacher again in Au in the Rhine Valley in the 1950s, on a temporary basis, until his retirement as an impoverished and outlawed private citizen. In 1971, he receives recognition from Yad Vashem as a “Righteous Among the Nations”, and in 1972 he dies in St. Gall.

It was not until 1993 that he was rehabilitated and soon after that the sentence against him was also overturned. In 1998, his family was compensated. Ruth Roduner, his daughter, uses the money to establish the Paul Grüninger Foundation, which has supported human rights activities ever since.

In 2012, the border bridge over the Old Rhine between Hohenems and Diepoldsau is named after him.5

Recommended reading:

Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998); Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005

1 SFA E 4260 (C) 1969/146 Volume 6: Conferences of the Cantonal Police Directors, minutes of the meeting of Aug. 17, 1938 in Bern. (quoted after Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005, p. 117-8.)

2 Quoted from Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993, p. 50.

3 Report of the Chief of the Police Department of 15 September 1938 to the FDJP, quoted after: Carl Ludwig, Switzerland's Refugee Policy since 1933 to the Present, Bern 1966/1957, p. 112.

4 Le Chef de la Division de Police du Département de Justice et Police, H. Rothmund, au Ministre de Suisse à La Haye, A. de Pury, 27 January 1939, Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz 1848-1945, Vol. 13 (1939-1940), Bern 1991, p. 22.

5 On Paul Grüninger's story, see Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Zurich 1993.

Grave of Paul Grüninger at the cemetery in Au (St. Gall)

Opening of the Paul Grueninger Bridge, May 6, 2012, Ruth Roduner-Grüninger and Robert Kreutner in the center.

Opening of the Paul Grueninger Bridge, May 6, 2012, Ruth Roduner-Grüninger and Robert Kreutner in the center.

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

23 Paul Grüninger

“Can't we close our borders better?” Paul Grüninger and Swiss refugee policy

Bern, August 17, 1938

On August 17, 1938 Heinrich Rothmund, head of the immigration police in the Federal Department of Justice and Police, invites the cantonal police directors to room 86 of the parliament building in Bern. The extraordinary conference is to discuss the situation at the border and how to deal with the growing number of refugees trying to enter Switzerland from the German Reich. One of the participants is the captain of the St. Gall cantonal police, Paul Grüninger.

Rothmund opens the conference with a report that makes the situation seem dramatic. Far more than 1000 illegal refugees were in Switzerland. And the German Reich would now also distribute German passports to all Austrians. One would have to think about extending the visa requirement for Austrians to all Germans. The Zurich police director Robert Briner, who is also president of the Swiss Central Office for Refugee Aid, provides the cue Rothmund was expecting:

“Can't we close our borders better? Removing refugees is more difficult than keeping them away.”

St. Gall councillor Valentin Keel speaks of the “cultural shame of the persecution of the Jews” in Germany, a remark that is not recorded in the minutes. Thurgau police chief Ernst Haudenschild has the following response:

“The greatest punishment for the German authorities is the deportation of all refugees. Today we are dealing with the Jews, in a few months probably other refugees from Germany. Our cantonal government has given us strict instructions to turn away all refugees. We have no political refugees and no Jewish refugees in our canton. You may order and decide what you like in Bern, our canton will not admit any refugees.”

It is Paul Grüninger who dares to openly object:

“The previous speaker's comments are surprising. The expulsion of the refugees is not possible, if only for reasons of humanity. We have to let many in. We have an interest in keeping these people together as much as possible so that controls can be carried out and also for hygienic reasons. If we turn people away, they will come in uncontrollably. Complete closure of the border is not possible.”1

Support for Grüninger comes above all from the representative of Graubünden, Department Secretary Dr. Bühler. The social democratic representatives from Basel and Schaffhausen, police director Brechbühl and councillor Bührer, also speak out – for the time being – against ruthless deportations and refoulement. The others, in line with Rothmund, demand the immediate closure of the borders.

In the following press release, there is no more mention of the dissenting opinions. The decision to close the border to refugees was unanimous. Two days later, the police directors are informed,

“that a further influx of illegal refugees cannot be tolerated. (...) Since the eastern border is difficult to protect, especially near Diepoldsau, the border control there was reinforced from the stocks of the volunteer border guard companies.”

Paul Grüninger, who openly spoke out against the border closure in the conference, had already been in conflict with the orders from Bern for weeks at this point.2

Born in St. Gall in 1891, Grüninger had initially pursued a career as a primary school teacher. And as a passionate footballer, he had won the Swiss championship in 1915 with his team, the St. Gall club SC Brühl, as a left winger. In 1919, Grüninger switched to the police service, where he was promoted to commander of the St. Gall cantonal police in 1925. And becomes president of his football club.

Wedding photo of Alice and Paul Grüninger, 1921

In 1938, Grüninger is confronted with the plight of the refugees. At first he reacted indecisively, then he obeyed his compassion more and more. Again and again, refugees who had managed to cross the border illegally came to his office in St. Gall and asked for a residence permit; more and more often he was called to the border himself to decide on the spot. And most of the time he decides in favor of the refugees. The Israelite Refugee Aid under Sidney Dreyfus sets up its own office in St. Gall. At the beginning of August, the refugee quarters in private accommodation and boarding houses are no longer sufficient. Grüninger sets up a refugee camp in an empty embroidery shop in Diepoldsau. The costs for this have to be covered by the Israelite Refugee Aid as the organization is otherwise responsible for the care of the refugees. Eventually Grüninger also begins to smuggle valuables across the border for the refugees.

With the closing of the border on August 18 and the order to admit no one, Grüninger and Dreyfus are left only with the choice of backdating the arrival of those people who still manage to cross the border afterwards. It is these life-saving “breaches of official duty” and “falsification of documents” for which Paul Grüninger is soon dismissed and put on trial.

Representatives of Switzerland, on the other hand, negotiate with the Germans about the visa requirement demanded by Rothmund. The German side proposes marking the passports of Jews and demands that Switzerland do the same.

A general marking of Jewish Swiss citizens is out of the question for Rothmund. As far as the refugees are concerned, he admittedly prefers another solution, not so offensive in the eyes of world public opinion, but just as effective: his own checks on who is Jewish and who is not. Four weeks after the conference, on September 15, 1938, he reports to the Federal Department of Justice and Police:

“We have succeeded to date in preventing the Judaization of Switzerland through systematic and careful work. (...) If we have the visa, Germany is completely free to give the emigrants papers as it wishes and does not need to designate them as such. We would find them out among those who would not be able to produce an Aryan identity card, a membership book of the Party, the German Labor Front (...) etc. (...) At the border we would have a clean order.”3

The German side, of course, does not want to accept a general visa requirement for all Reich citizens. So they finally agree on the J-stamp in the passports of German Jews. The stigmatization becomes official. In January, Rothmund writes with satisfaction to the Swiss envoy in The Hague, Arthur-Edouard de Pury:

“We have not fought for twenty years with the means of the immigration police against the increase of foreign infiltration and especially against the Judaization of Switzerland, in order to have emigrants forced upon us today.“4

At the beginning of 1939, pressure grows on Grüninger, as well as on government councillor Keel, who must fear for his re-election. Rothmund demands an investigation into the “irregularities” in the canton of St. Gall that have come to his attention. And the right wing nationalist “Vaterländische Verband” threatens to make public the “scandal” of illegal entries. On April 3, 1939, Grüninger was suspended, and finally dishonorably dismissed with the deprivation of his pension rights. In 1940, he was sentenced to a fine.

Grüninger is without means. The Jewish community does not dare to support him openly. Refugee aid as a whole is now threatened. The textile industrialist Elias Sternbuch, Recha Sternbuch's brother-in-law, finally gives him a job selling raincoats in Basle. But Grüninger is no good as a businessman. After unsuccessful attempts as a sales representative, he becomes a primary school teacher again in Au in the Rhine Valley in the 1950s, on a temporary basis, until his retirement as an impoverished and outlawed private citizen. In 1971, he receives recognition from Yad Vashem as a “Righteous Among the Nations”, and in 1972 he dies in St. Gall.

It was not until 1993 that he was rehabilitated and soon after that the sentence against him was also overturned. In 1998, his family was compensated. Ruth Roduner, his daughter, uses the money to establish the Paul Grüninger Foundation, which has supported human rights activities ever since.

In 2012, the border bridge over the Old Rhine between Hohenems and Diepoldsau is named after him.5

Recommended reading:

Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993 (1998); Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005

1 SFA E 4260 (C) 1969/146 Volume 6: Conferences of the Cantonal Police Directors, minutes of the meeting of Aug. 17, 1938 in Bern. (quoted after Jörg Krummenacher, Flüchtiges Glück. Die Flüchtlinge im Grenzkanton St. Gallen zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Zurich 2005, p. 117-8.)

2 Quoted from Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Geschichten von Flucht und Hilfe. Zurich 1993, p. 50.

3 Report of the Chief of the Police Department of 15 September 1938 to the FDJP, quoted after: Carl Ludwig, Switzerland's Refugee Policy since 1933 to the Present, Bern 1966/1957, p. 112.

4 Le Chef de la Division de Police du Département de Justice et Police, H. Rothmund, au Ministre de Suisse à La Haye, A. de Pury, 27 January 1939, Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz 1848-1945, Vol. 13 (1939-1940), Bern 1991, p. 22.

5 On Paul Grüninger's story, see Stefan Keller, Grüningers Fall. Zurich 1993.

Grave of Paul Grüninger at the cemetery in Au (St. Gall)