Heinz Müller> December 1938

25 Heinz Müller

“These are things that are deeply, deeply ingrained”: Heinz Müller recalls his childhood as a refugee

Hohenems – Diepoldsau, December 1938

“My mother just told me: ... we're going to cross the border there, and when you get there, you have to cry, you have to say you're cold and you want to see your dad, and so on and so forth, just do something, then maybe there's a possibility that they'll let us through. Because at that time they actually still let the Jews out of Austria or out of the German Reich, they were happy about everyone who went out.”[1]

Heinz Müller crosses the Diepoldsau border from Hohenems into Switzerland with his mother in December 1938. At the time he is five years old. His father, Tobias Müller, a furrier from Romania, had trained as a cook in a Jewish emigration camp in Vienna in 1938 and fled to Switzerland in the fall of 1938, where he found work as a cook in the Diepoldsau refugee camp. In 2006 in Basle, Heinz Müller recalls his own escape.

“And so we did it then. It was also really bitterly cold in that December as there was a lot of snow, and as my father entered Switzerland illegally at that time, he broke in and sprained his ankle when crossing the Old Rhine, and happened to come to the house of the Landjäger, the policeman who was responsible for the area. And so we were able after much hassle, because we had practically nothing in our hands, I don't know what kind of papers we had, we probably already had something, a paper, but we didn't have any passports. And I don't really remember how we got across the Swiss border.

I can only remember that it was very foggy and that we didn't actually see my father coming, we only heard him. How he whistled and called. And then we got there and it may be, of course, that with the agreement of the Landjäger, that it was a little easier for us, because there was practically no one at the border. So we were more or less alone there at the customs house, that is, we were taken into the customs house, and there they squeezed us, and then they said: Get lost! And that was actually our good fortune, because from there, from Hohenems, many people who were in the camp and who were then put back, were mostly thrown out again via Hohenems.”

From the refugee camp Diepoldsau, the family later has to move to Basel, where Tobias Müller takes over the management of the kitchen in the refugee camp “Sommercasino”. Again and again, the family is asked by the Swiss Immigration Police to continue their emigration elsewhere. It is not until long after the war that Heinz Müller succeeds in acquiring Swiss citizenship.

“These are things that have been very deeply ingrained in the children, and that has certainly caused one or the other a certain trauma. So as one said, also the children - not only the adults - also the children have stood under a certain pressure and have experienced this so to speak. And that's the strange thing now, that when I was asked later, now you're Swiss ... I've experienced so many things that actually ... yes, I'm Swiss on paper, but that I would have the feeling that I really belong there, or that I would be a part of it, I've experienced so many things that make it difficult for me to identify myself, as it were, as they say. Although now another 65 years have gone by, which have actually passed. But these are things that are deeply, deeply buried. And these are things that you don't forget. And just as one has been pushed here, how far, how it stands with the emigration, one had to show every three months what one has done for the further emigration and so on. So the Swiss have absolutely not made it easy for us to be here. And now I'm a part of it, of Switzerland, but I'm my own part.”

Müller Family at Diepoldsau, January 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Tobias Müller as a cook in the Diepoldsau camp, Passover 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

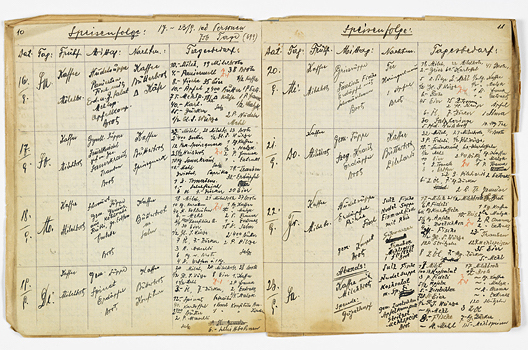

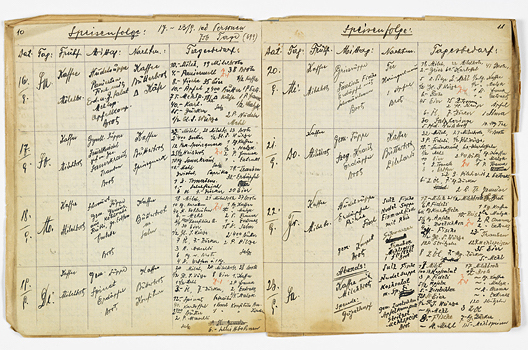

The kitchen book kept by Tobias Müller of the camp kitchen in Diepoldsau, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

25 Heinz Müller

“These are things that are deeply, deeply ingrained”: Heinz Müller recalls his childhood as a refugee

Hohenems – Diepoldsau, December 1938

“My mother just told me: ... we're going to cross the border there, and when you get there, you have to cry, you have to say you're cold and you want to see your dad, and so on and so forth, just do something, then maybe there's a possibility that they'll let us through. Because at that time they actually still let the Jews out of Austria or out of the German Reich, they were happy about everyone who went out.”[1]

Heinz Müller crosses the Diepoldsau border from Hohenems into Switzerland with his mother in December 1938. At the time he is five years old. His father, Tobias Müller, a furrier from Romania, had trained as a cook in a Jewish emigration camp in Vienna in 1938 and fled to Switzerland in the fall of 1938, where he found work as a cook in the Diepoldsau refugee camp. In 2006 in Basle, Heinz Müller recalls his own escape.

“And so we did it then. It was also really bitterly cold in that December as there was a lot of snow, and as my father entered Switzerland illegally at that time, he broke in and sprained his ankle when crossing the Old Rhine, and happened to come to the house of the Landjäger, the policeman who was responsible for the area. And so we were able after much hassle, because we had practically nothing in our hands, I don't know what kind of papers we had, we probably already had something, a paper, but we didn't have any passports. And I don't really remember how we got across the Swiss border.

I can only remember that it was very foggy and that we didn't actually see my father coming, we only heard him. How he whistled and called. And then we got there and it may be, of course, that with the agreement of the Landjäger, that it was a little easier for us, because there was practically no one at the border. So we were more or less alone there at the customs house, that is, we were taken into the customs house, and there they squeezed us, and then they said: Get lost! And that was actually our good fortune, because from there, from Hohenems, many people who were in the camp and who were then put back, were mostly thrown out again via Hohenems.”

From the refugee camp Diepoldsau, the family later has to move to Basel, where Tobias Müller takes over the management of the kitchen in the refugee camp “Sommercasino”. Again and again, the family is asked by the Swiss Immigration Police to continue their emigration elsewhere. It is not until long after the war that Heinz Müller succeeds in acquiring Swiss citizenship.

“These are things that have been very deeply ingrained in the children, and that has certainly caused one or the other a certain trauma. So as one said, also the children - not only the adults - also the children have stood under a certain pressure and have experienced this so to speak. And that's the strange thing now, that when I was asked later, now you're Swiss ... I've experienced so many things that actually ... yes, I'm Swiss on paper, but that I would have the feeling that I really belong there, or that I would be a part of it, I've experienced so many things that make it difficult for me to identify myself, as it were, as they say. Although now another 65 years have gone by, which have actually passed. But these are things that are deeply, deeply buried. And these are things that you don't forget. And just as one has been pushed here, how far, how it stands with the emigration, one had to show every three months what one has done for the further emigration and so on. So the Swiss have absolutely not made it easy for us to be here. And now I'm a part of it, of Switzerland, but I'm my own part.”

Müller Family at Diepoldsau, January 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

Tobias Müller as a cook in the Diepoldsau camp, Passover 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems

The kitchen book kept by Tobias Müller of the camp kitchen in Diepoldsau, 1939

Archive of the Jewish Museum Hohenems