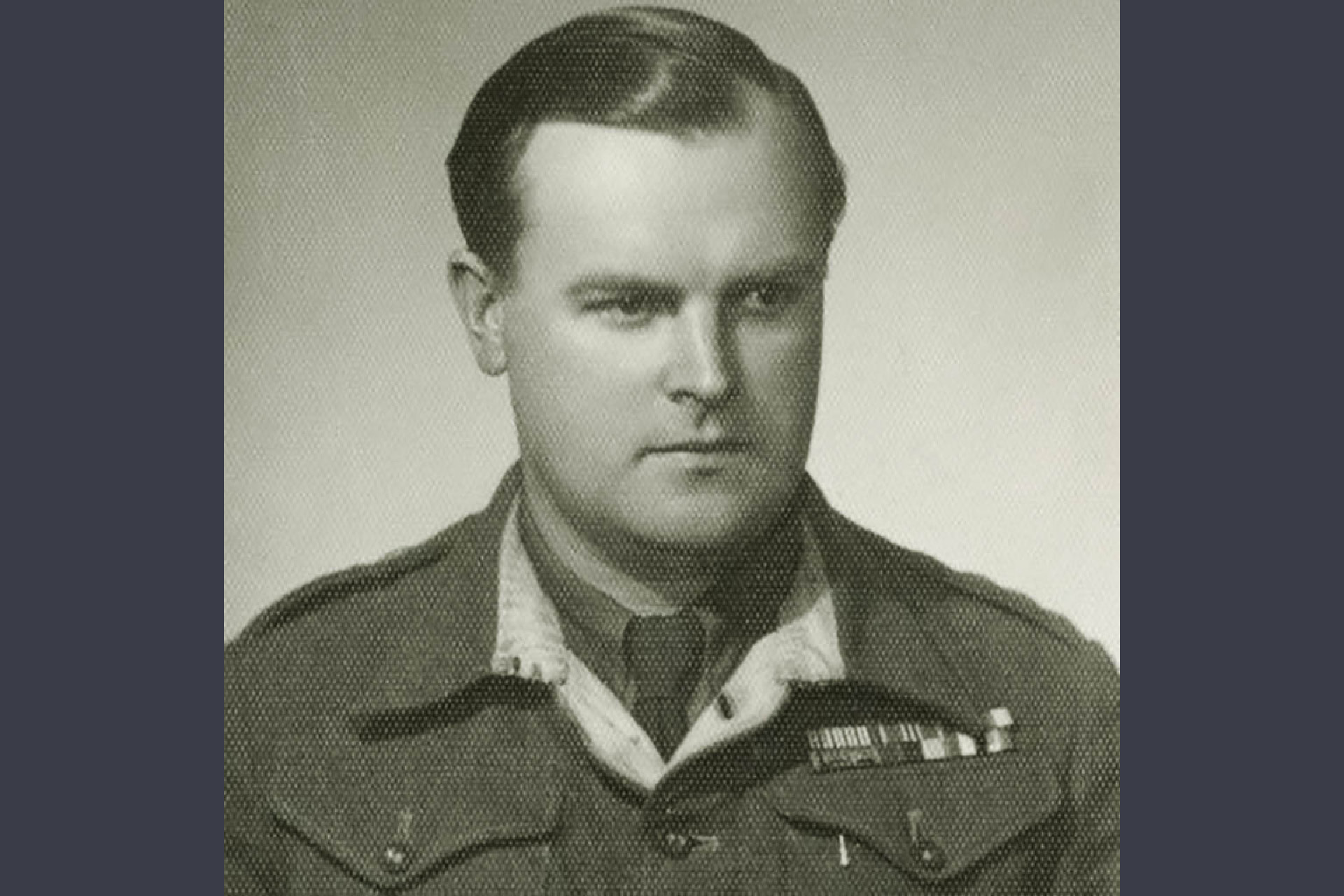

Bohumil Pavel Snižek> August 26, 1941

34 Bohumil Snižek

From Prague to Gibraltar and back – via Vorarlberg, Switzerland, and Dunkirk. Bohumil Pavel Snižek on his way through Europe

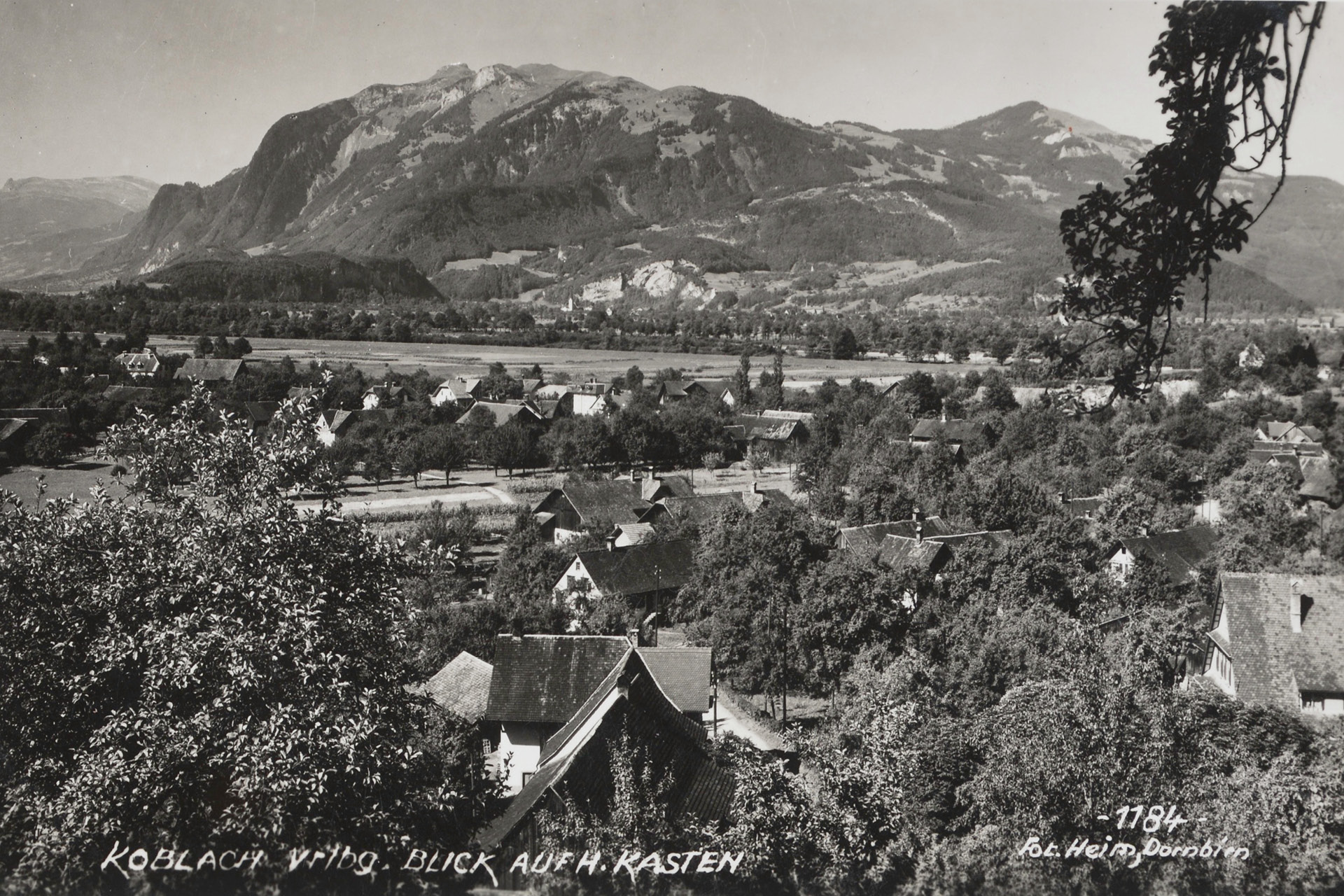

Koblach, August 28, 1941

“I creep quietly through the thicket. The riverbank is controlled, the trail betrays that the soldiers guarding the border often pass this way. I wait a while, venture as far as the river, but quickly turn back.”

A young Czech wants to cross the Rhine. It is August 26, 1941.

“Quickly but quietly I slip into the water and swim, the bundle of my clothes tied around my neck with a belt, floating on the water. I am already in the middle of the river. My hearing is strained; as soon as the sound of gunfire is heard, I must dive. I am already approaching the other bank, the tension is easing. I step out of the shallow bank and catch my breath. I try to look back, it seems to be getting light. The fog moves across the river. I wipe the water off me and get dressed. A strange feeling comes over me. I am beyond the reach of the power of the Great German Empire!”[1]

Two weeks earlier he has left his parents' house in Chrast, a small town in the middle of the then “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” in order to reach Switzerland. He then bicycled 240 kilometers to the west, as far as Pilsen. From there he crossed the border into the German Reich on foot and continued by train. Via Eger, Marktredwitz and Munich, further via Lindau and Hohenems to Götzis.

At 1:00 a.m. he arrives there, searches and finds the river and reaches the other bank. He walks along a canal, dodging Swiss border posts. In the next village, Oberriet, the world has already woken up. Schoolchildren are already on their way. No one takes notice of him. He greets other people on the street as if it were normal.

“A warm balm for a scratched soul (...) I could smell the aroma of real coffee with fat milk, the smell of freshly baked bread from the bakery. I haven't eaten anything for the third day.”

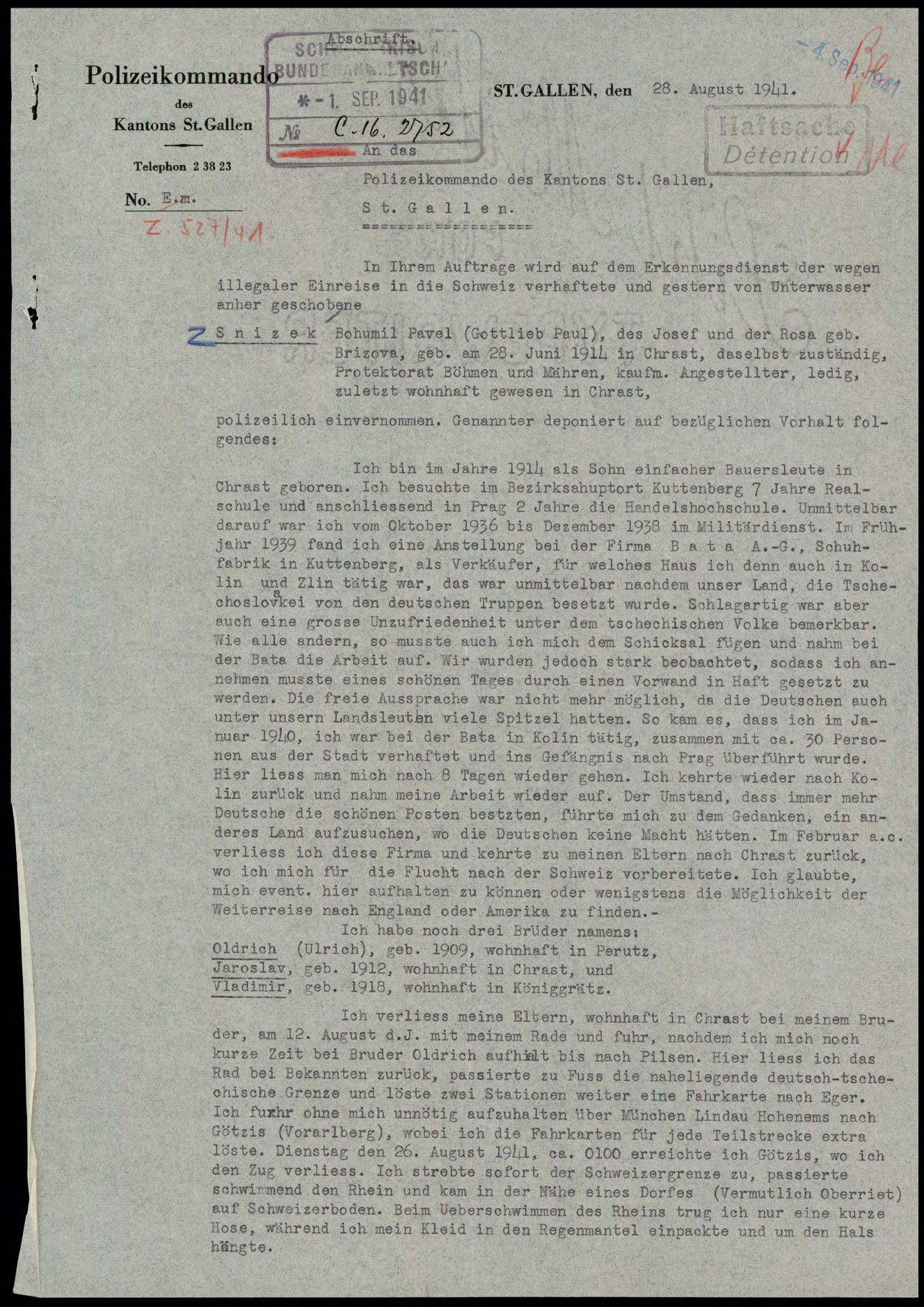

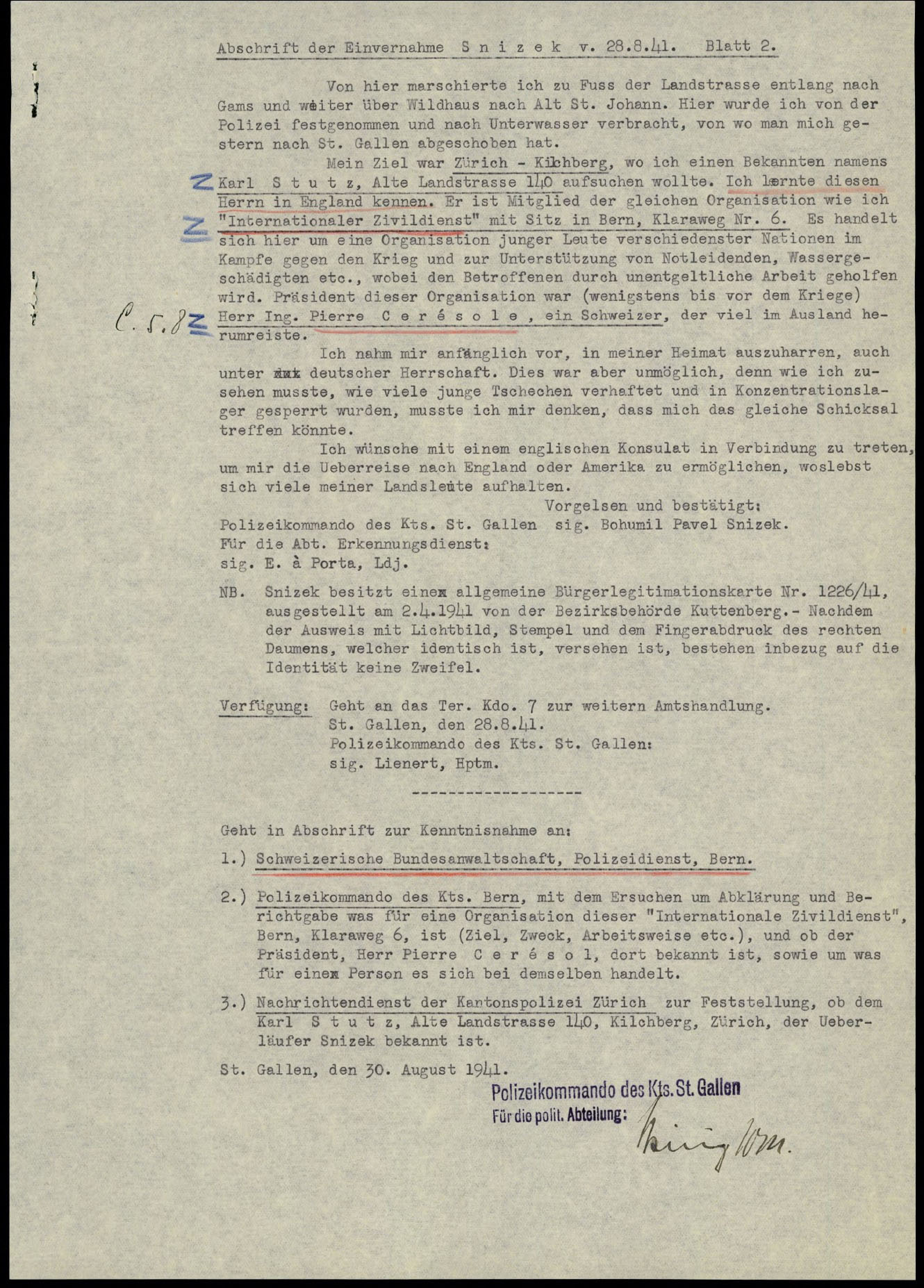

On foot, he continues on his way, along the country road to Gams and up to Wildhaus. His destination is Zurich. But in Toggenburg, in Alt St. Johann, he is arrested. In St. Gall, he is interrogated by the Political Department of the Cantonal Police Command. The young Czech identifies himself as Bohumil Pavel Snižek. He is twenty-seven years old and full of hope that everything will turn out well for him. Because he has a lot of plans. And he already has a lot behind him. He finished his military service at the end of 1938 - shortly afterwards the Wehrmacht marched in and crushed Czechoslovakia.

“Suddenly, however, a great discontent was noticeable among the Czech people.”

This is how the Swiss policeman records Snižek's interrogation.

“However, we were strongly observed, so that I had to assume one fine day to be put in custody by a pretext. Free speech was no longer possible, since the Germans had many informers among our compatriots as well. So it happened that in January 1940 (...) I was arrested together with about 30 people from the town and transferred to the prison in Prague. Here they let me go again after 8 days.”[2]

But by now, the decision matured in him to flee from the Nazi occupation.

Snižek states that he wants to visit an acquaintance in Zurich whom he knows from his student days in England – and from their common membership in the pacifist organization “International Civil Service”. Since 1920, the “Service Civil International” sought ways to promote international understanding and provided disaster relief, under its Swiss president Pierre Cérésole.

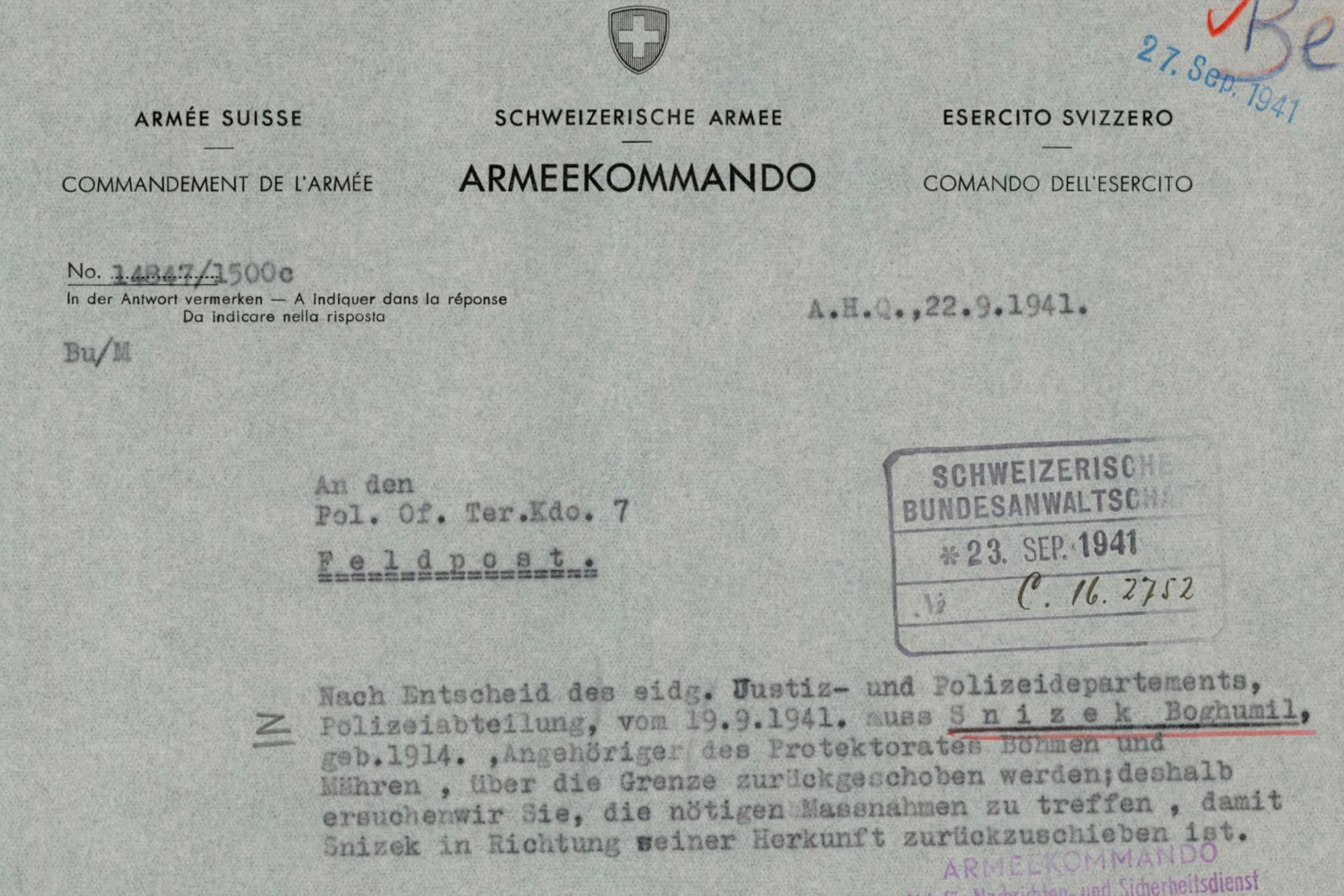

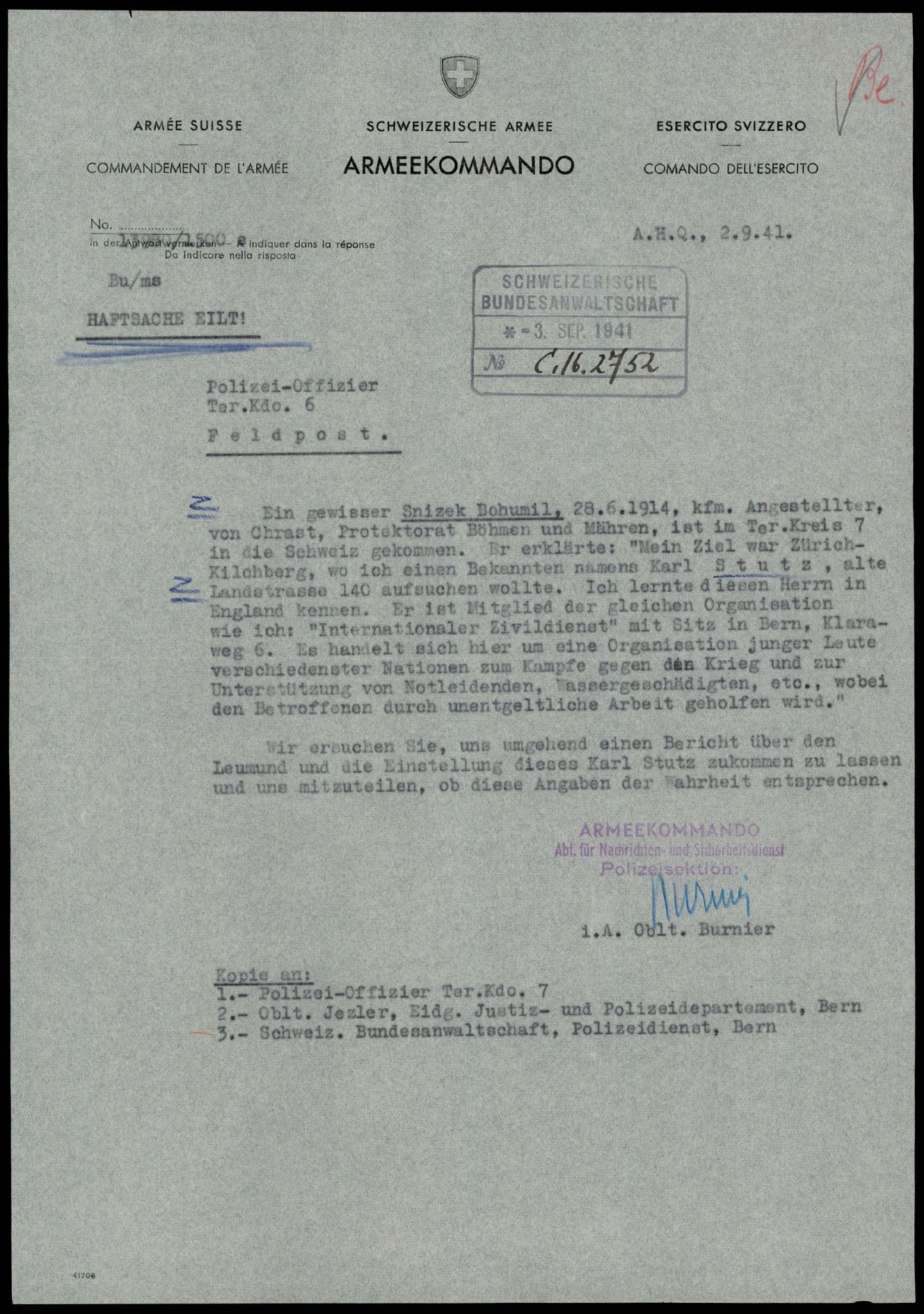

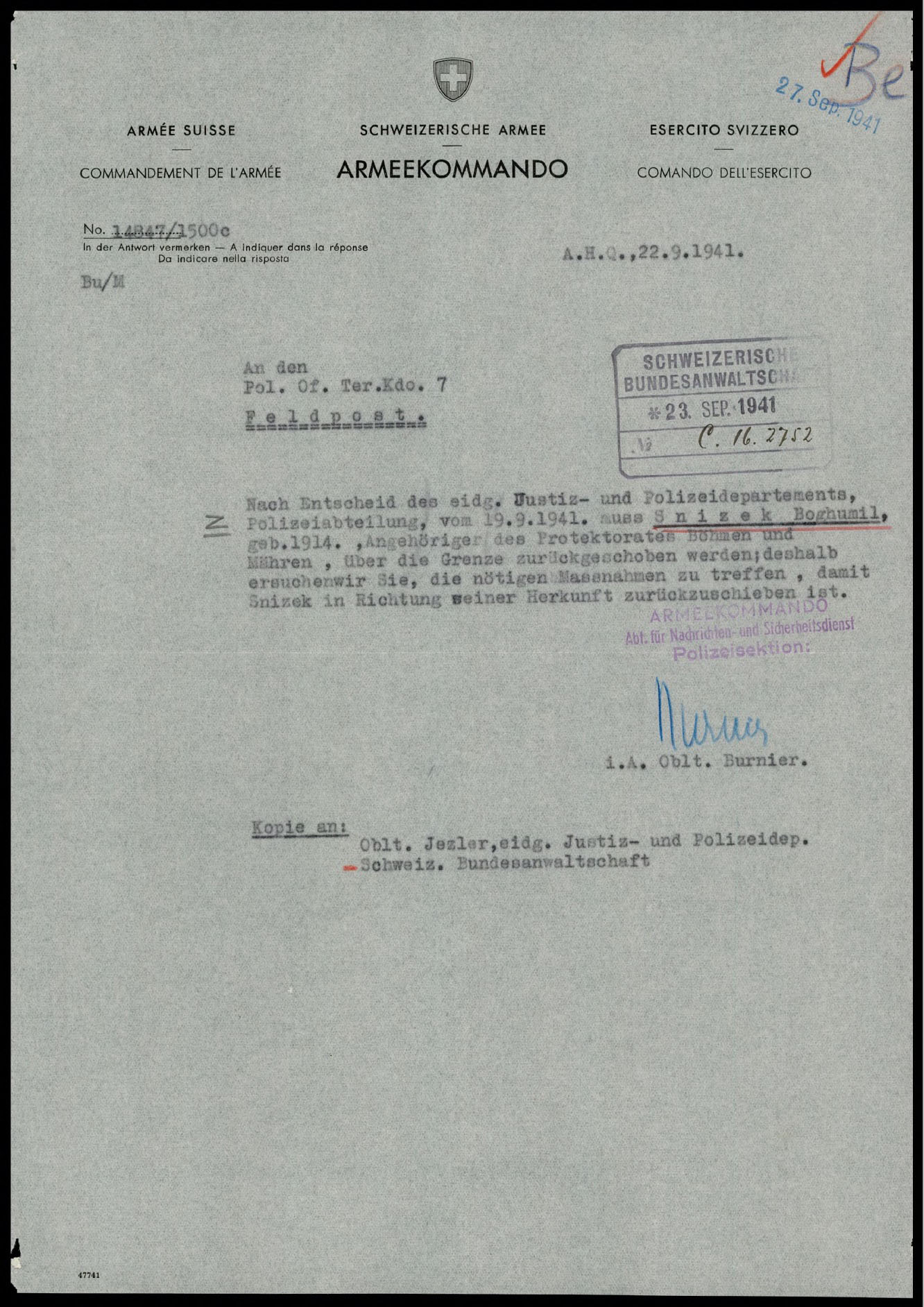

Snižek remains in St. Gall prison and is interrogated several times. The Swiss army command makes inquiries. And decides to deport Snižek to the German Reich. Could it have something to do with the fact that Cérésole, a radical pacifist and conscientious objector, had already served several prison sentences in Switzerland?

But instead of being deported, Snižek was handed an address in Geneva by the prison warden on October 17 – and told to go there directly. It was the representative of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in London: Jaromír Kopecký, the liaison with the resistance in Europe.

For half a year Snižek worked under his guidance in Geneva. Then he finally wants to go on to England to join the Czechoslovak army in exile.

But the way there still leads across many obstacles and borders. First, he and a comrade named Jan Kocmanek have to make their way to Marseille to report to the Czechoslovak relief organization of the lawyer Oldřich Dubina.

For a few days the two are hidden in a farmhouse before continuing to Toulouse and from there to Banyuls on the Spanish border. On May 2, a smuggler takes the two, along with eight other Czechs, over the foothills of the Pyrenees to Port Bou. From that moment on, Bohumil Snižek calls himself Paul Snow and assumes the identity of an English soldier.

In Barcelona, they are arrested and held in the Casela Modelo prison. At the beginning of July they are taken from there to the Spanish concentration camp Miranda de Ebro. Snižek is still threatened with extradition to the Germans. But in the meantime the Spanish fascists try to get by as servants of two masters, and to preserve their neutrality in the war. So the Czechs are not extradited, but instead send to Gibraltar in September, to the British. Exactly where they want to go. At the end of October, Snižek, alias Paul Snow, is flown to England with his comrades. And there, too, interrogations await him. His odyssey seems all too adventurous to the British military. Is he possibly a German agent?

Finally, Snižek is able to dispel the doubts. And joins the Czechoslovak Independent Brigade in the British Army.

Two years later, at the end of August 1944, he is transferred to France as a lieutenant in the Czechoslovak Armored Brigade. There, the Czechoslovak Exile Army is deployed by the British against the German positions in Dunkirk. The attempt to take the port city on October 28, 1944 fails. It remains the only major battle the Allies allowed the Exile Army to fight. The Czechoslovak brigades had to continue the siege of Dunkirk until the German surrender on May 8, 1945.

When Bohumil Snižek is finally allowed to return home, Prague is both liberated and occupied by the Red Army. No glory awaits returnees from the West like him, but at best oblivion – or trials for “American espionage” and “cosmopolitanism.” Bohumil Snižek died in 1959 as a result of his war wounds. He wrote his so far unpublished autobiography under the name Paul Snow.

Source:

Zdeněk Holenka, Bojová cetsa Bohumila Snižka. Z Protektorátu a zpět do ČSR (5. květen 1941 - 20. květen 1945), master thesis 2008 (Bohumil Snižeks Path of Fight. From the Protectorate and back into Czechoslovakia (May 5, 1941 – May 20, 1945).

[1] Paul Snow (Bohumil Snižek, Cesta Nadeje (Paths of Hope), unpublished autobiography, quoted after Zdeněk Holenka, Bojová cetsa Bohumila Snižka. Z Protektorátu a zpět do ČSR (5. květen 1941 - 20. květen 1945), master thesis 2008 (Bohumil Snižeks Path of Fight. From the Protectorate and back into Czechoslovakia (May 5, 1941 – May 20, 1945), p. 29.

[2] Police interrogation protocol of Bohumil Snižek, 28.8.1941; Swiss Federal Archive, Bern, E4320B#1990/266#2848

Aerial view of Oberriet and Koblach, photo: Werner Friedli, 1947

ETH Library Zurich, Picture Archive, Stiftung Luftbild

St. Gallen Police Command, Interrogation of Bohumil Snizek, August 28, 1941

St. Gallen Police Command, Interrogation of Bohumil Snizek, August 28, 1941

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Dossier Bohumil Pavel Snizek

Nachforschungen des Schweizerischen Armeekommandos, 2. September 1941

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Bohumil Pavel Snizek

Swiss Army Command, Order for the Deportation of Bumil Snizek, September 22, 1941.

Swiss Army Command, Order for the Deportation of Bumil Snizek, September 22, 1941.

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Bohumil Snizek

34 Bohumil Snižek

From Prague to Gibraltar and back – via Vorarlberg, Switzerland, and Dunkirk. Bohumil Pavel Snižek on his way through Europe

Koblach, August 28, 1941

“I creep quietly through the thicket. The riverbank is controlled, the trail betrays that the soldiers guarding the border often pass this way. I wait a while, venture as far as the river, but quickly turn back.”

A young Czech wants to cross the Rhine. It is August 26, 1941.

“Quickly but quietly I slip into the water and swim, the bundle of my clothes tied around my neck with a belt, floating on the water. I am already in the middle of the river. My hearing is strained; as soon as the sound of gunfire is heard, I must dive. I am already approaching the other bank, the tension is easing. I step out of the shallow bank and catch my breath. I try to look back, it seems to be getting light. The fog moves across the river. I wipe the water off me and get dressed. A strange feeling comes over me. I am beyond the reach of the power of the Great German Empire!”[1]

Two weeks earlier he has left his parents' house in Chrast, a small town in the middle of the then “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” in order to reach Switzerland. He then bicycled 240 kilometers to the west, as far as Pilsen. From there he crossed the border into the German Reich on foot and continued by train. Via Eger, Marktredwitz and Munich, further via Lindau and Hohenems to Götzis.

At 1:00 a.m. he arrives there, searches and finds the river and reaches the other bank. He walks along a canal, dodging Swiss border posts. In the next village, Oberriet, the world has already woken up. Schoolchildren are already on their way. No one takes notice of him. He greets other people on the street as if it were normal.

“A warm balm for a scratched soul (...) I could smell the aroma of real coffee with fat milk, the smell of freshly baked bread from the bakery. I haven't eaten anything for the third day.”

On foot, he continues on his way, along the country road to Gams and up to Wildhaus. His destination is Zurich. But in Toggenburg, in Alt St. Johann, he is arrested. In St. Gall, he is interrogated by the Political Department of the Cantonal Police Command. The young Czech identifies himself as Bohumil Pavel Snižek. He is twenty-seven years old and full of hope that everything will turn out well for him. Because he has a lot of plans. And he already has a lot behind him. He finished his military service at the end of 1938 - shortly afterwards the Wehrmacht marched in and crushed Czechoslovakia.

“Suddenly, however, a great discontent was noticeable among the Czech people.”

This is how the Swiss policeman records Snižek's interrogation.

“However, we were strongly observed, so that I had to assume one fine day to be put in custody by a pretext. Free speech was no longer possible, since the Germans had many informers among our compatriots as well. So it happened that in January 1940 (...) I was arrested together with about 30 people from the town and transferred to the prison in Prague. Here they let me go again after 8 days.”[2]

But by now, the decision matured in him to flee from the Nazi occupation.

Snižek states that he wants to visit an acquaintance in Zurich whom he knows from his student days in England – and from their common membership in the pacifist organization “International Civil Service”. Since 1920, the “Service Civil International” sought ways to promote international understanding and provided disaster relief, under its Swiss president Pierre Cérésole.

Snižek remains in St. Gall prison and is interrogated several times. The Swiss army command makes inquiries. And decides to deport Snižek to the German Reich. Could it have something to do with the fact that Cérésole, a radical pacifist and conscientious objector, had already served several prison sentences in Switzerland?

But instead of being deported, Snižek was handed an address in Geneva by the prison warden on October 17 – and told to go there directly. It was the representative of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in London: Jaromír Kopecký, the liaison with the resistance in Europe.

For half a year Snižek worked under his guidance in Geneva. Then he finally wants to go on to England to join the Czechoslovak army in exile.

But the way there still leads across many obstacles and borders. First, he and a comrade named Jan Kocmanek have to make their way to Marseille to report to the Czechoslovak relief organization of the lawyer Oldřich Dubina.

For a few days the two are hidden in a farmhouse before continuing to Toulouse and from there to Banyuls on the Spanish border. On May 2, a smuggler takes the two, along with eight other Czechs, over the foothills of the Pyrenees to Port Bou. From that moment on, Bohumil Snižek calls himself Paul Snow and assumes the identity of an English soldier.

In Barcelona, they are arrested and held in the Casela Modelo prison. At the beginning of July they are taken from there to the Spanish concentration camp Miranda de Ebro. Snižek is still threatened with extradition to the Germans. But in the meantime the Spanish fascists try to get by as servants of two masters, and to preserve their neutrality in the war. So the Czechs are not extradited, but instead send to Gibraltar in September, to the British. Exactly where they want to go. At the end of October, Snižek, alias Paul Snow, is flown to England with his comrades. And there, too, interrogations await him. His odyssey seems all too adventurous to the British military. Is he possibly a German agent?

Finally, Snižek is able to dispel the doubts. And joins the Czechoslovak Independent Brigade in the British Army.

Two years later, at the end of August 1944, he is transferred to France as a lieutenant in the Czechoslovak Armored Brigade. There, the Czechoslovak Exile Army is deployed by the British against the German positions in Dunkirk. The attempt to take the port city on October 28, 1944 fails. It remains the only major battle the Allies allowed the Exile Army to fight. The Czechoslovak brigades had to continue the siege of Dunkirk until the German surrender on May 8, 1945.

When Bohumil Snižek is finally allowed to return home, Prague is both liberated and occupied by the Red Army. No glory awaits returnees from the West like him, but at best oblivion – or trials for “American espionage” and “cosmopolitanism.” Bohumil Snižek died in 1959 as a result of his war wounds. He wrote his so far unpublished autobiography under the name Paul Snow.

Source:

Zdeněk Holenka, Bojová cetsa Bohumila Snižka. Z Protektorátu a zpět do ČSR (5. květen 1941 - 20. květen 1945), master thesis 2008 (Bohumil Snižeks Path of Fight. From the Protectorate and back into Czechoslovakia (May 5, 1941 – May 20, 1945).

[1] Paul Snow (Bohumil Snižek, Cesta Nadeje (Paths of Hope), unpublished autobiography, quoted after Zdeněk Holenka, Bojová cetsa Bohumila Snižka. Z Protektorátu a zpět do ČSR (5. květen 1941 - 20. květen 1945), master thesis 2008 (Bohumil Snižeks Path of Fight. From the Protectorate and back into Czechoslovakia (May 5, 1941 – May 20, 1945), p. 29.

[2] Police interrogation protocol of Bohumil Snižek, 28.8.1941; Swiss Federal Archive, Bern, E4320B#1990/266#2848

Aerial view of Oberriet and Koblach, photo: Werner Friedli, 1947

ETH Library Zurich, Picture Archive, Stiftung Luftbild