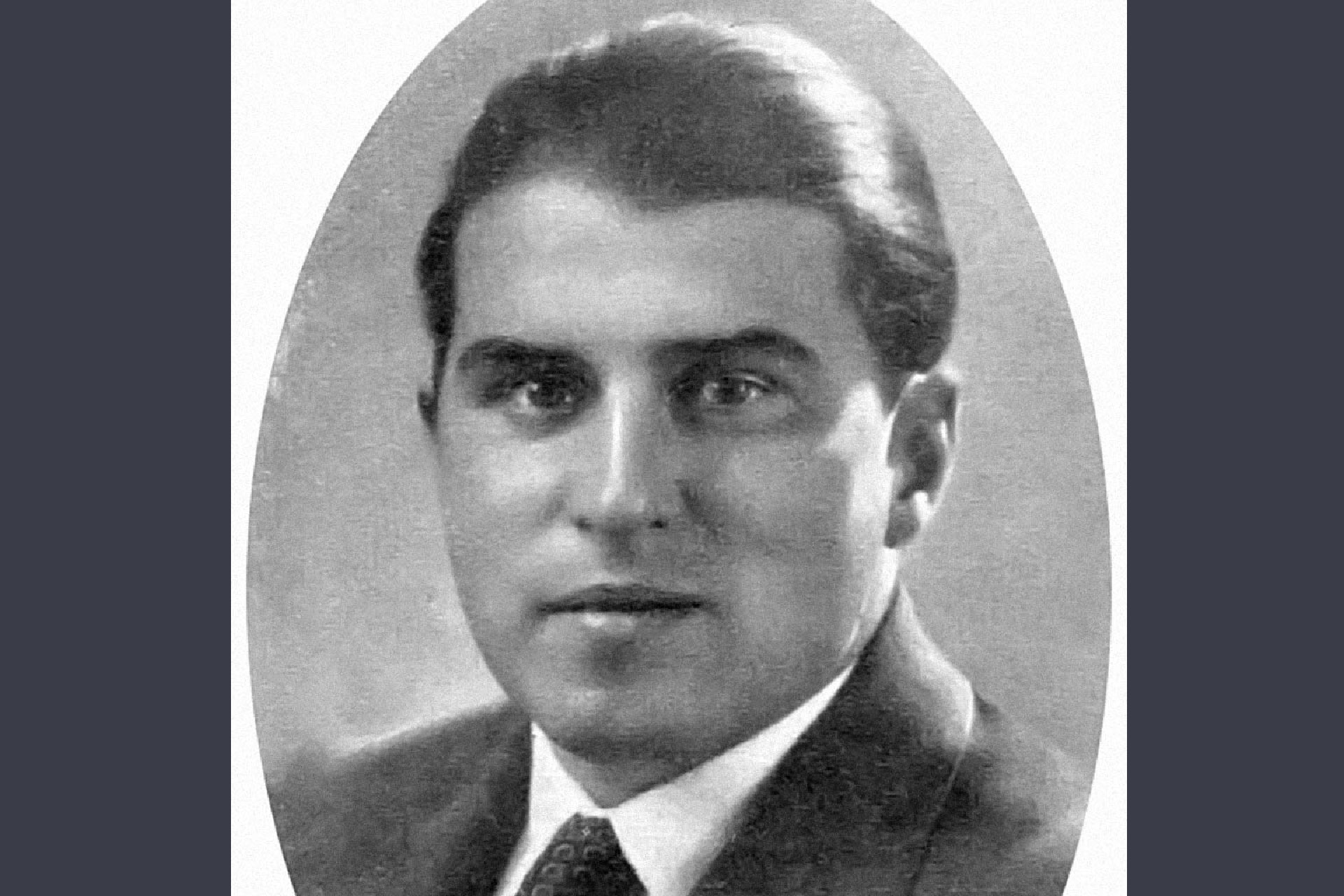

Carl Zuckmayer> March 15, 1938

41 Carl Zuckmayer

Mass flight after the Anschluss: Carl Zuckmayer is checked

Feldkirch train station, March 15, 1938

After the Anschluss of Austria to the German Reich, thousands of people flee Vienna. Jews and also political opponents of the Nazis try to reach Switzerland by train via Feldkirch, Liechtenstein, and Buchs. Switzerland had not yet introduced any visa requirement. Among the refugees, like Walter Mehring and Gina Kaus, Jura Soyfer and Hertha Pauli, is the German writer Carl Zuckmayer.

In 1933, he had emigrated to Austria and his writings were burned in the German Reich. On March 15, 1938, he managed to escape at the last second while a National Socialist rolling squad stormed first his house in Henndorf near Salzburg, then his apartment in Vienna, to arrest him. As a “half-Jew,” Zuckmayer, who had once been so popular in Germany, aroused the particular fury of the Nazis. In his autobiography, “A Part of Myself,” he describes his arrival in Feldkirch on his way to Zurich.

“As the train slowly pulled into Feldkirch and the glaring cone of headlights was seen, I had little hope. I actually felt nothing and thought nothing at that moment. A cold tension had filled me. But all instincts were focused on rescue. I think today: if this is how the fox feels when he hears the pack?

‘All out, with luggage! The train is being cleared. Carriers!’ I shouted. ‘Carry yourselves,’ a voice shouted, ‘there are no carriers for you.’ One was, as an occupant of this train, already only in the plural. (...) I was led across the long platform of the station, while my luggage remained behind and fell to thoroughness. At the very end of the station, where it became pitch dark, some barracks were visible. There was a garlicky smell of damp carbide, and the chalky glow of a bicycle lamp wavered over the barrack entrance.

Inside the barracks, a blond skinny person in SS uniform sat behind a table, wearing steel goggles and looking overworked and undernourished. In front of the table stood a man with his coat collar turned up and his head bowed, who had apparently just been interrogated.

‘To the station for removal,’ I heard the officer's voice, ‘if overcrowded to the local jail. Next gentleman please.’ (...)

‘Carl Zuckmayer,’ he said. – ‘I see.’

He stared at the passport, leafed through it, his face becoming thoughtful. Again and again he stared at the first page. I could tell that the five-year validity irritated him: Jews in those days only got passports for six months, if that. Mine had been issued earlier at the German consulate in Salzburg, where they proceeded correctly and were sympathetic to me.”[1]

Zuckmayer succeeds in impressing the young SS man with his fearless demeanor and reference to his war decorations. And he gets permission to continue his journey. But he still has to wait in the station inn.

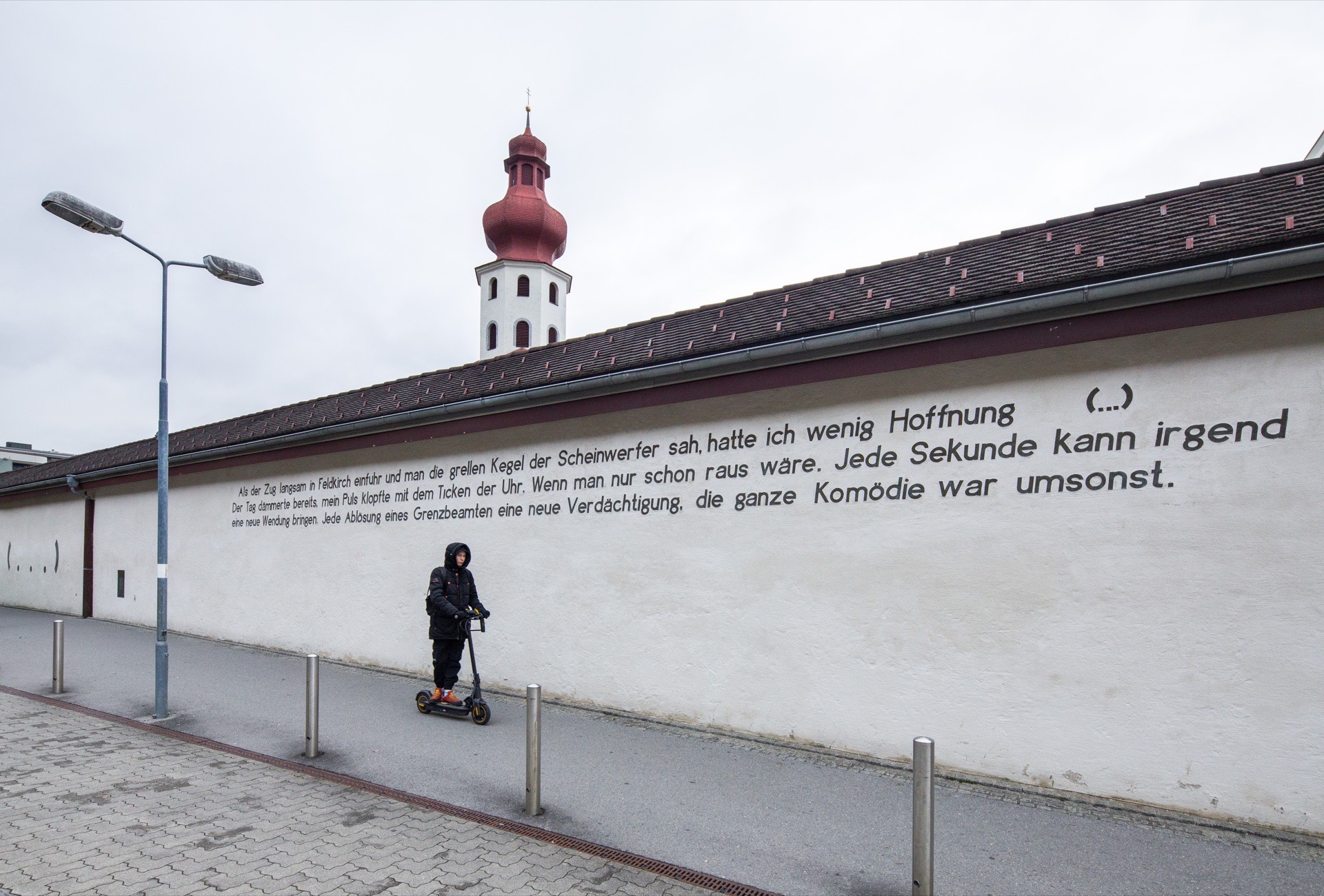

“The day was already dawning, my pulse was pounding with the ticking of the clock. If only one were out already. Every second can bring some new turn. Every relief of a border guard a new suspicion, all the comedy was for nothing.”

Finally, his train is moving.

“The sky was glassy green and cloudless, the sun glimmering on the snow as the train passed the border. The Swiss customs officials came in and emitted friendly maws. Everything was over. I was on a train, and it wasn't going in the direction of Dachau.”

[1] Carl Zuckmayer, Als wär's ein Stück von mir. Horen der Freundschaft. Frankfurt/Main 1966; Frankfurt/Main 1994, p. 103-105.

41 Carl Zuckmayer

Mass flight after the Anschluss: Carl Zuckmayer is checked

Feldkirch train station, March 15, 1938

After the Anschluss of Austria to the German Reich, thousands of people flee Vienna. Jews and also political opponents of the Nazis try to reach Switzerland by train via Feldkirch, Liechtenstein, and Buchs. Switzerland had not yet introduced any visa requirement. Among the refugees, like Walter Mehring and Gina Kaus, Jura Soyfer and Hertha Pauli, is the German writer Carl Zuckmayer.

In 1933, he had emigrated to Austria and his writings were burned in the German Reich. On March 15, 1938, he managed to escape at the last second while a National Socialist rolling squad stormed first his house in Henndorf near Salzburg, then his apartment in Vienna, to arrest him. As a “half-Jew,” Zuckmayer, who had once been so popular in Germany, aroused the particular fury of the Nazis. In his autobiography, “A Part of Myself,” he describes his arrival in Feldkirch on his way to Zurich.

“As the train slowly pulled into Feldkirch and the glaring cone of headlights was seen, I had little hope. I actually felt nothing and thought nothing at that moment. A cold tension had filled me. But all instincts were focused on rescue. I think today: if this is how the fox feels when he hears the pack?

‘All out, with luggage! The train is being cleared. Carriers!’ I shouted. ‘Carry yourselves,’ a voice shouted, ‘there are no carriers for you.’ One was, as an occupant of this train, already only in the plural. (...) I was led across the long platform of the station, while my luggage remained behind and fell to thoroughness. At the very end of the station, where it became pitch dark, some barracks were visible. There was a garlicky smell of damp carbide, and the chalky glow of a bicycle lamp wavered over the barrack entrance.

Inside the barracks, a blond skinny person in SS uniform sat behind a table, wearing steel goggles and looking overworked and undernourished. In front of the table stood a man with his coat collar turned up and his head bowed, who had apparently just been interrogated.

‘To the station for removal,’ I heard the officer's voice, ‘if overcrowded to the local jail. Next gentleman please.’ (...)

‘Carl Zuckmayer,’ he said. – ‘I see.’

He stared at the passport, leafed through it, his face becoming thoughtful. Again and again he stared at the first page. I could tell that the five-year validity irritated him: Jews in those days only got passports for six months, if that. Mine had been issued earlier at the German consulate in Salzburg, where they proceeded correctly and were sympathetic to me.”[1]

Zuckmayer succeeds in impressing the young SS man with his fearless demeanor and reference to his war decorations. And he gets permission to continue his journey. But he still has to wait in the station inn.

“The day was already dawning, my pulse was pounding with the ticking of the clock. If only one were out already. Every second can bring some new turn. Every relief of a border guard a new suspicion, all the comedy was for nothing.”

Finally, his train is moving.

“The sky was glassy green and cloudless, the sun glimmering on the snow as the train passed the border. The Swiss customs officials came in and emitted friendly maws. Everything was over. I was on a train, and it wasn't going in the direction of Dachau.”

[1] Carl Zuckmayer, Als wär's ein Stück von mir. Horen der Freundschaft. Frankfurt/Main 1966; Frankfurt/Main 1994, p. 103-105.