Familie Leopold> September 16, 1944

44 Leopold Family

“We Bludenz citizens... it's a great story“. The Leopold family goes into hiding.

Bludenz, September 16, 1944

“We enter the valley of the River Ill through a tunnel and the mountains of Bludenz appear. To the left is Hoher Fraßen, to the right Mondspitze, Schillerkopf, etc. In Bludenz there is bright sunshine. We hand in part of our luggage and go to the post office. We post the first greetings to friends and I phone the office of the Regional Councilor. Kühnl answers. We have been allocated to the Arlberger Hof Hotel and are well received and given a comfortable room. After a general clean-up we fetch the hand luggage at the station. After Lunch at the Arlberger Hof I take my first afternoon nap in Bludenz. We take a short walk to a viewing point and Anneliese cries. After supper I fall into a deep sleep.”[1]

No one suspects that Dr. Kurt Freiherr, the new tax official at the Bludenz district office, who arrives in town with his family on September 16, 1944, is actually a Jewish refugee. In December 1943, Walter Leopold had managed to forge a military service passport in Leipzig in the name of Kurt Freiherr. And to invent a new biography for himself step by step – as a bombed-out accountant from Mannheim, where, as he knew, not much was left of the city and its offices.

Together with his family, Walter Leopold had already been living underground for more than a year at this point, hidden by non-Jewish friends, or on the street. In November 1938, like thousands of Jewish men, he had been deported to Buchenwald, and as a decorated World War [II??] participant, had been released again – probably in exchange for the assurance extorted from him that he would leave the country. He had stayed and continued to work in the administration of the Jewish community.

When he received orders in September 1942 to join his wife Hilda and five-year-old daughter Anneliese for deportation on September 19 to Theresienstadt, the Nazis' deceptive “showcase ghetto”, the Leopolds went into hiding.

But Walter Leopold, a left-wing socialist and self-confident Jew, possesses not only the will to survive but also wit and ingenuity. He sends applications to German authorities.

And in May 1944 he gets his chance. The district office in Bludenz is looking for an experienced tax official. And who, if not he, is experienced enough for that. On May 25 he travels to Bludenz, the place he knows from earlier holiday trips and hiking tours. He actually succeeds in winning the post for himself. And this despite the fact that he freely admits that he is not a party member. He knows exactly how much he can impute to the fictitious Dr. Freiherr. And which archives would still reveal his non-existence despite the destruction of the bombings. So he takes up his duties on September 18. On the 27th he notes:

“The snow has gone from the heights, but it’s raining hard. One freezes in the office and one cannot see the mountains anymore. Never mind, we have no visitor’s tax to pay like on our earlier visit, and don’t throw our money out of window. For we live her, and after winter another spring will come. If we live to see it! We, the residents of Bludenz. My god, isn’t that a great story.”[2]

Not only he and his wife Hilda now have to play comedy. Their now seven-year-old daughter Anneliese, with whom they go on excursions to the Tschengla and the rest of the mountain world, must now also master her role as a Protestant in Catholic Bludenz and at school.

“Well, my… like I say, I don't remember any of the details mainly because my parents didn't let me in on the details. But I do remember, our trip to Austria, where the officials of course came and wanted to see the papers and I didn’t know they were forged. (…) I mean I was just plain afraid because it was an official, you know, official to me was a Nazi. And probably could have been, I’m not sure. So we finally get to Austria and my father says to me: ‘Well, you know, we still cannot reveal our identity, but we’re free, as far as that goes. We don’t have to worry that a Nazi is going to come and try to shoot you or, uhm, we don’t have to hide in one room.“[3]

First they are allocated a flat in Wichnerstraße above the Koch tyre shop, then they can move into the newly built Südtirolersiedlung, the quarter for relocated Southern Tyroleans.

“And I remember then Christmas, we had a Christmas tree, you know. And we had, uhm, because we had people that came to visit us, and we were Protestant, you know, of course you couldn't get away with, I mean, Protestants weren’t so well liked to begin with, you know. Because it was predominantly Catholic. And, uhm, so, you know, I remember being very sacrilegious one day and we were eating some kind of a, not a hot dog, but some kind of … and I took the peel and held it on the Christmas tree and mum says: ‘You don’t do that!’, you know, I said: ‘We don’t really need this Christmas tree.’”

The family keeps up the game until the liberation in May 1945. Walter Leopold only succeeds with difficulty in convincing the French of his true identity. They don't quite know how to deal with him. He loses his job at the district administration office. Although he would probably like to stay in Bludenz. At least the family now gets a spacious flat that had belonged to a high Nazi functionary. To their surprise, they find an imposing menorah there, with which they celebrate Hanukkah again for the first time in December.

Walter Leopold is visited by clergymen who try to convince him to become a Catholic. Maybe then he could even become mayor. But converting is out of the question for him. Anneliese's grades at school are getting worse. Her classmates accuse her that they, the Jews, killed Jesus. They don't belong here.

“You know, the traumatic experience that I had over there, ah, I don't think I ever really got over that. That was very hard for me to, you know, but the bombs and that I think I got over when we were in Austria. … But Austria really was, if I had anything to say about my childhood, if I had any happy memories, they would have been of Austria. Even though the last part wasn’t good.”

In 1950, the family emigrates to the USA and settles in Cincinnati. Leopold waits for a job at the university - and works as a night watchman in a slaughterhouse, then in a textile factory. In 1952, he dies of a heart attack.

“I always portray his death as, you know, like Moses led the people to the Promised Land but he couldn’t enjoy it, you know. He died, he survived all this war and all these hardships, but once we were comfortable, you know, he died.”

[1] Diary of Walter Leopold. Published in English translation: Walter Leopold (with Les Leopold), Defiant German. Defiant Jew. A Holocaust Memoir From Inside the Third Reich. Amsterdam 2020, p. 193.

[3] Interview with Anneliese Yosafat (née Leopold) by Joanne Centa, 18.12.1995; USC Shoah Foundation.

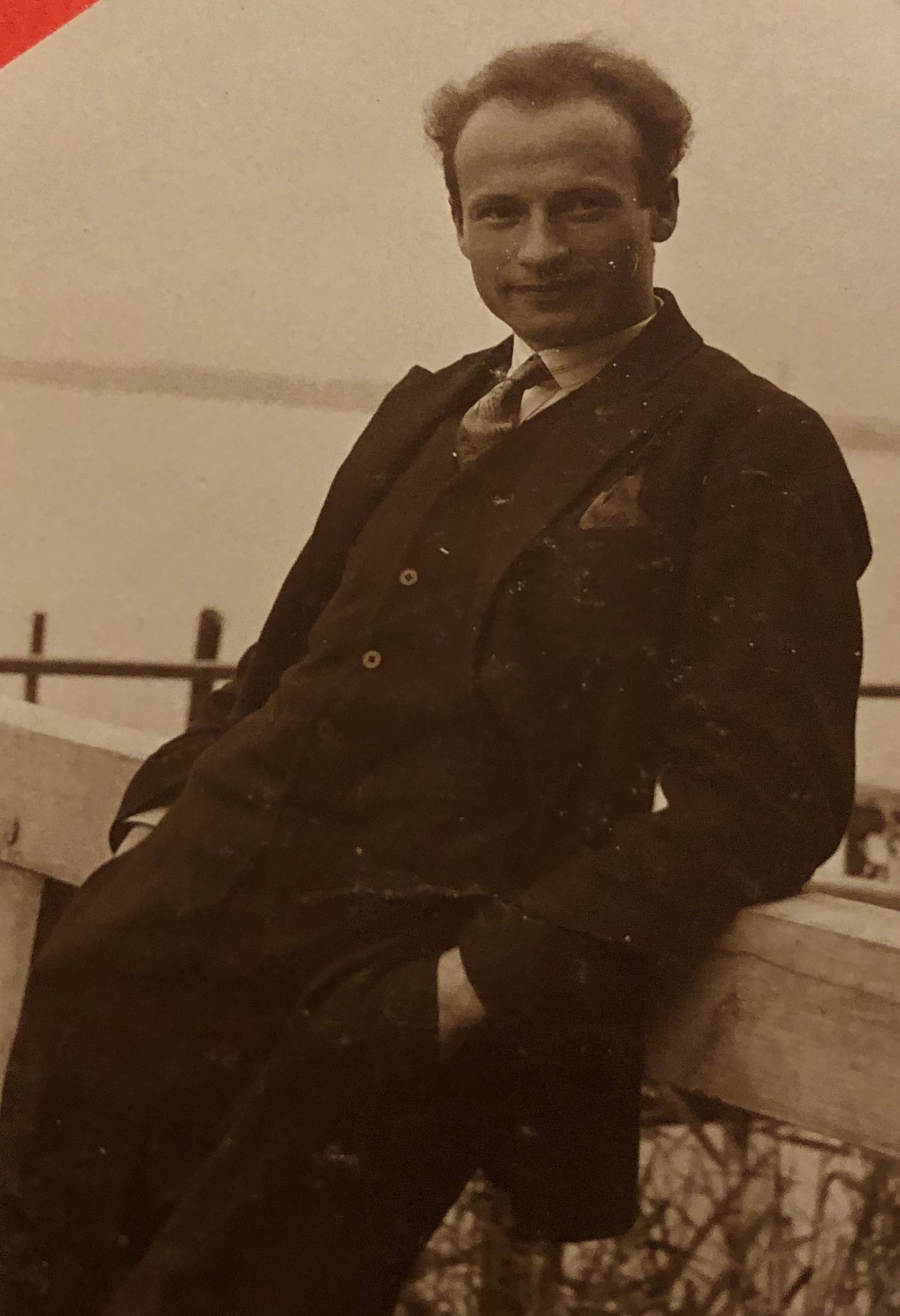

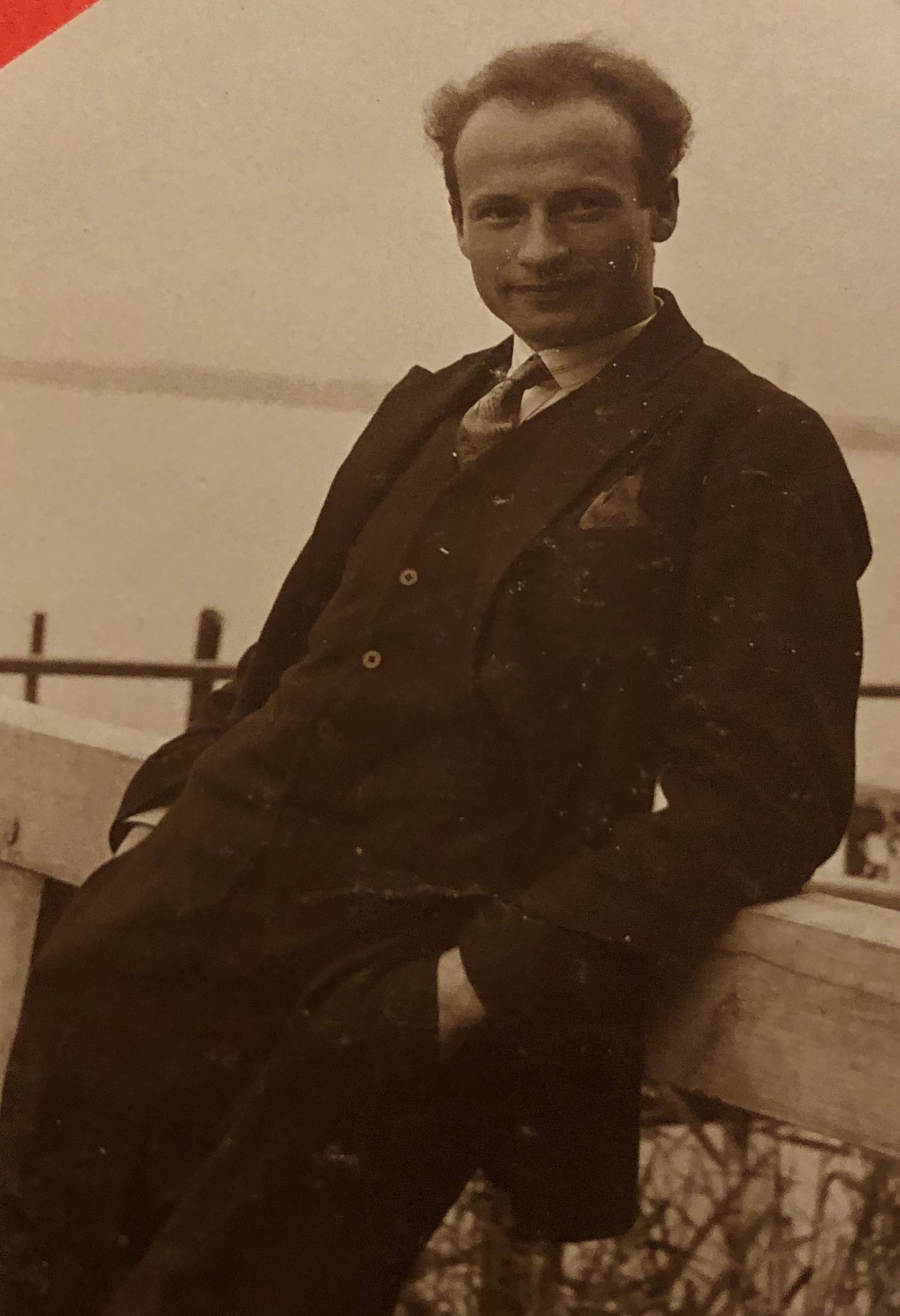

Walter Leopold, about 1938

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

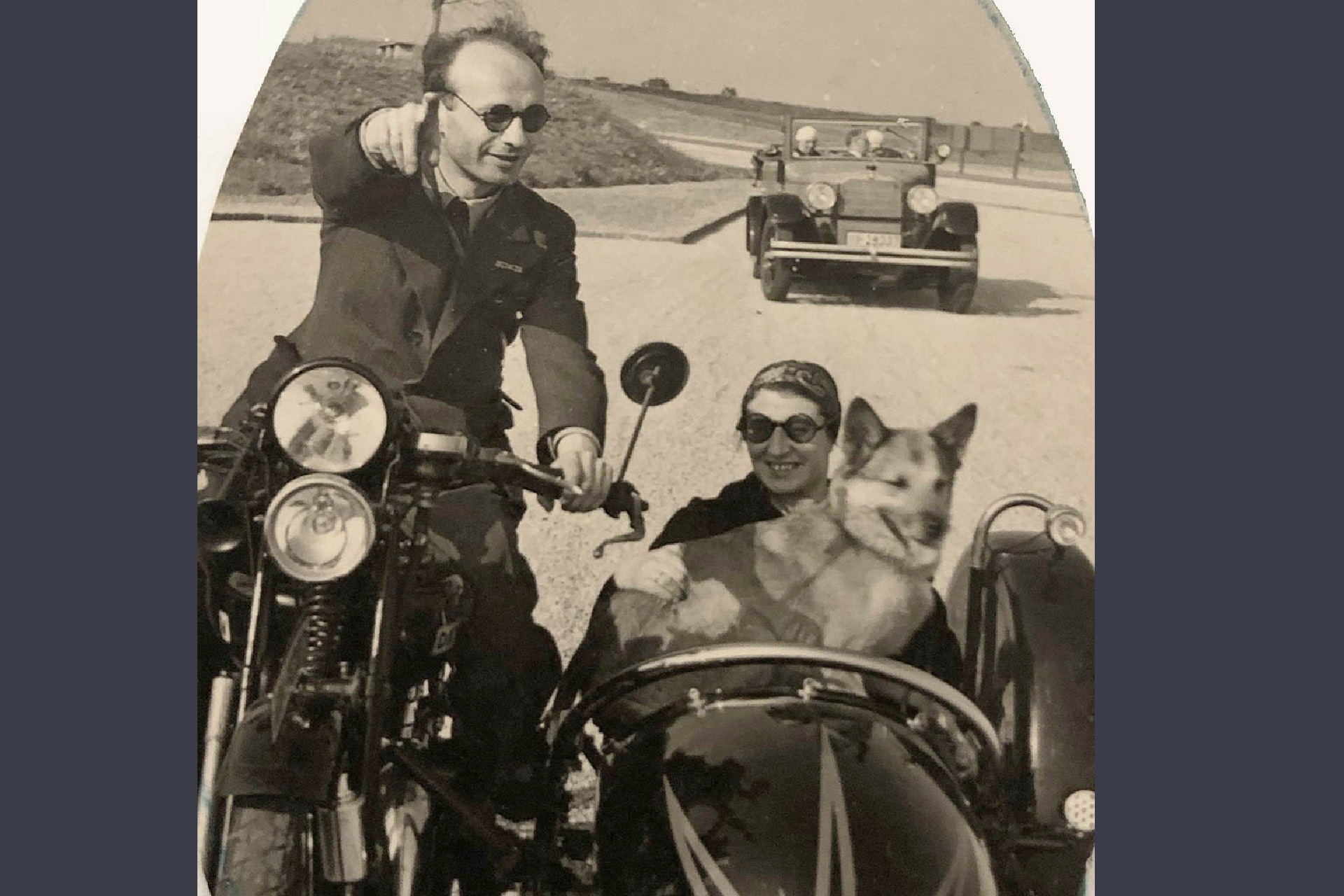

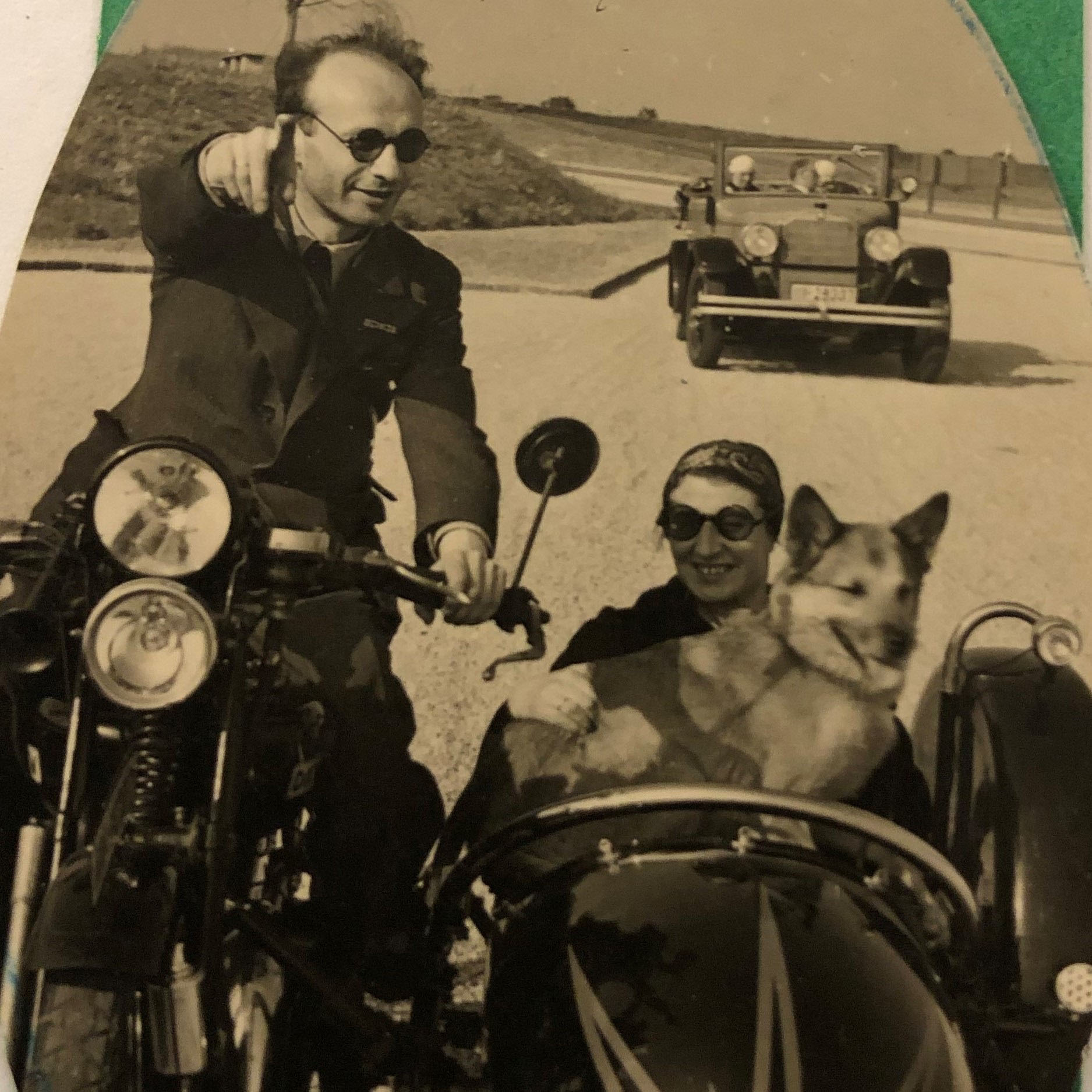

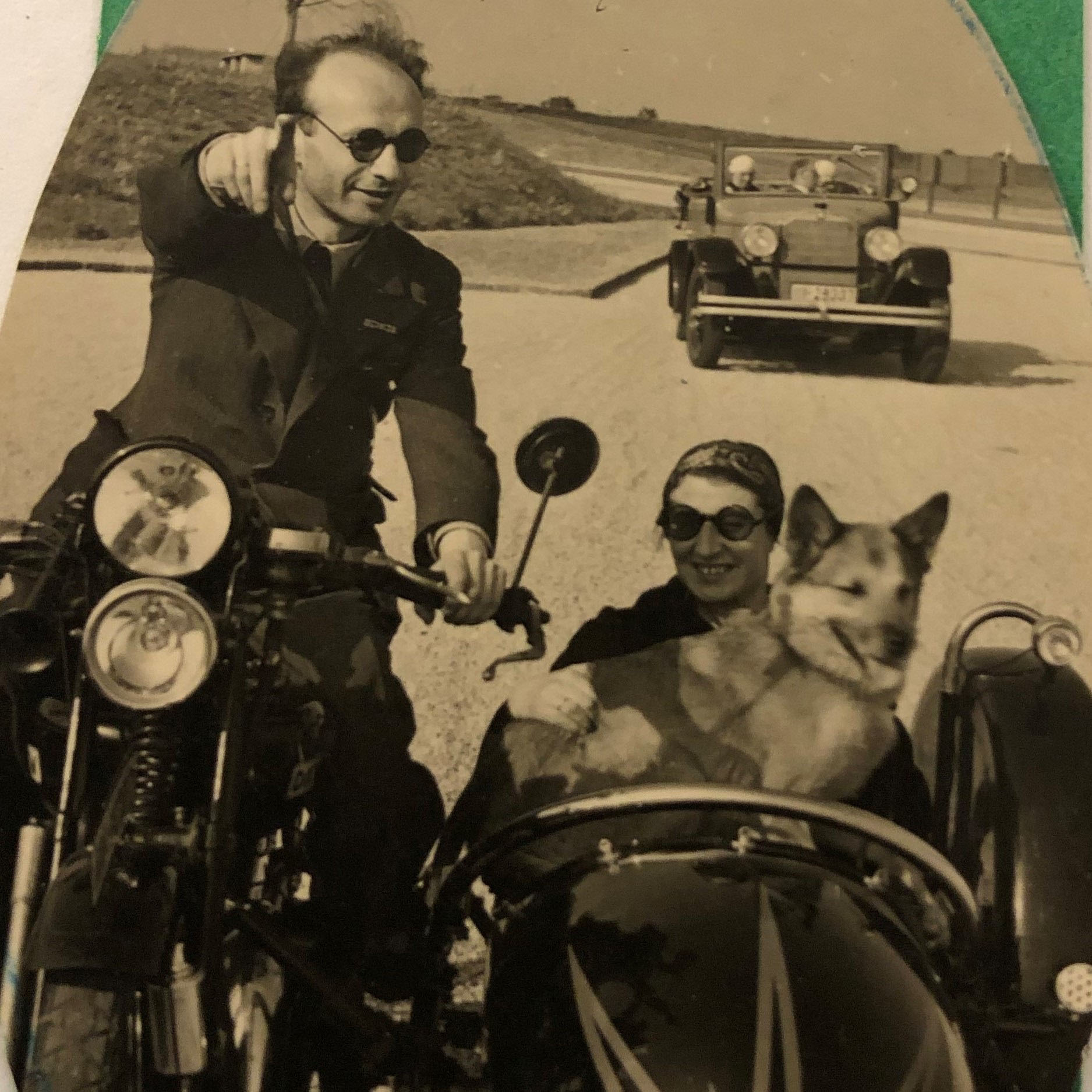

Walter and Hilda Leopold with their dog Mäuslein, around 1935

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Anneliese, Hilda and Walter Leopold, Bludenz, about 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Hilda and Walter Leopold, about 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Anneliese Leopold, Bludenz 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

44 Leopold Family

“We Bludenz citizens... it's a great story“. The Leopold family goes into hiding.

Bludenz, September 16, 1944

“We enter the valley of the River Ill through a tunnel and the mountains of Bludenz appear. To the left is Hoher Fraßen, to the right Mondspitze, Schillerkopf, etc. In Bludenz there is bright sunshine. We hand in part of our luggage and go to the post office. We post the first greetings to friends and I phone the office of the Regional Councilor. Kühnl answers. We have been allocated to the Arlberger Hof Hotel and are well received and given a comfortable room. After a general clean-up we fetch the hand luggage at the station. After Lunch at the Arlberger Hof I take my first afternoon nap in Bludenz. We take a short walk to a viewing point and Anneliese cries. After supper I fall into a deep sleep.”[1]

No one suspects that Dr. Kurt Freiherr, the new tax official at the Bludenz district office, who arrives in town with his family on September 16, 1944, is actually a Jewish refugee. In December 1943, Walter Leopold had managed to forge a military service passport in Leipzig in the name of Kurt Freiherr. And to invent a new biography for himself step by step – as a bombed-out accountant from Mannheim, where, as he knew, not much was left of the city and its offices.

Together with his family, Walter Leopold had already been living underground for more than a year at this point, hidden by non-Jewish friends, or on the street. In November 1938, like thousands of Jewish men, he had been deported to Buchenwald, and as a decorated World War [II??] participant, had been released again – probably in exchange for the assurance extorted from him that he would leave the country. He had stayed and continued to work in the administration of the Jewish community.

When he received orders in September 1942 to join his wife Hilda and five-year-old daughter Anneliese for deportation on September 19 to Theresienstadt, the Nazis' deceptive “showcase ghetto”, the Leopolds went into hiding.

But Walter Leopold, a left-wing socialist and self-confident Jew, possesses not only the will to survive but also wit and ingenuity. He sends applications to German authorities.

And in May 1944 he gets his chance. The district office in Bludenz is looking for an experienced tax official. And who, if not he, is experienced enough for that. On May 25 he travels to Bludenz, the place he knows from earlier holiday trips and hiking tours. He actually succeeds in winning the post for himself. And this despite the fact that he freely admits that he is not a party member. He knows exactly how much he can impute to the fictitious Dr. Freiherr. And which archives would still reveal his non-existence despite the destruction of the bombings. So he takes up his duties on September 18. On the 27th he notes:

“The snow has gone from the heights, but it’s raining hard. One freezes in the office and one cannot see the mountains anymore. Never mind, we have no visitor’s tax to pay like on our earlier visit, and don’t throw our money out of window. For we live her, and after winter another spring will come. If we live to see it! We, the residents of Bludenz. My god, isn’t that a great story.”[2]

Not only he and his wife Hilda now have to play comedy. Their now seven-year-old daughter Anneliese, with whom they go on excursions to the Tschengla and the rest of the mountain world, must now also master her role as a Protestant in Catholic Bludenz and at school.

“Well, my… like I say, I don't remember any of the details mainly because my parents didn't let me in on the details. But I do remember, our trip to Austria, where the officials of course came and wanted to see the papers and I didn’t know they were forged. (…) I mean I was just plain afraid because it was an official, you know, official to me was a Nazi. And probably could have been, I’m not sure. So we finally get to Austria and my father says to me: ‘Well, you know, we still cannot reveal our identity, but we’re free, as far as that goes. We don’t have to worry that a Nazi is going to come and try to shoot you or, uhm, we don’t have to hide in one room.“[3]

First they are allocated a flat in Wichnerstraße above the Koch tyre shop, then they can move into the newly built Südtirolersiedlung, the quarter for relocated Southern Tyroleans.

“And I remember then Christmas, we had a Christmas tree, you know. And we had, uhm, because we had people that came to visit us, and we were Protestant, you know, of course you couldn't get away with, I mean, Protestants weren’t so well liked to begin with, you know. Because it was predominantly Catholic. And, uhm, so, you know, I remember being very sacrilegious one day and we were eating some kind of a, not a hot dog, but some kind of … and I took the peel and held it on the Christmas tree and mum says: ‘You don’t do that!’, you know, I said: ‘We don’t really need this Christmas tree.’”

The family keeps up the game until the liberation in May 1945. Walter Leopold only succeeds with difficulty in convincing the French of his true identity. They don't quite know how to deal with him. He loses his job at the district administration office. Although he would probably like to stay in Bludenz. At least the family now gets a spacious flat that had belonged to a high Nazi functionary. To their surprise, they find an imposing menorah there, with which they celebrate Hanukkah again for the first time in December.

Walter Leopold is visited by clergymen who try to convince him to become a Catholic. Maybe then he could even become mayor. But converting is out of the question for him. Anneliese's grades at school are getting worse. Her classmates accuse her that they, the Jews, killed Jesus. They don't belong here.

“You know, the traumatic experience that I had over there, ah, I don't think I ever really got over that. That was very hard for me to, you know, but the bombs and that I think I got over when we were in Austria. … But Austria really was, if I had anything to say about my childhood, if I had any happy memories, they would have been of Austria. Even though the last part wasn’t good.”

In 1950, the family emigrates to the USA and settles in Cincinnati. Leopold waits for a job at the university - and works as a night watchman in a slaughterhouse, then in a textile factory. In 1952, he dies of a heart attack.

“I always portray his death as, you know, like Moses led the people to the Promised Land but he couldn’t enjoy it, you know. He died, he survived all this war and all these hardships, but once we were comfortable, you know, he died.”

[1] Diary of Walter Leopold. Published in English translation: Walter Leopold (with Les Leopold), Defiant German. Defiant Jew. A Holocaust Memoir From Inside the Third Reich. Amsterdam 2020, p. 193.

[3] Interview with Anneliese Yosafat (née Leopold) by Joanne Centa, 18.12.1995; USC Shoah Foundation.

Walter Leopold, about 1938

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Walter and Hilda Leopold with their dog Mäuslein, around 1935

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Anneliese, Hilda and Walter Leopold, Bludenz, about 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Hilda and Walter Leopold, about 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA

Anneliese Leopold, Bludenz 1945

Private Archive Les Leopold, USA