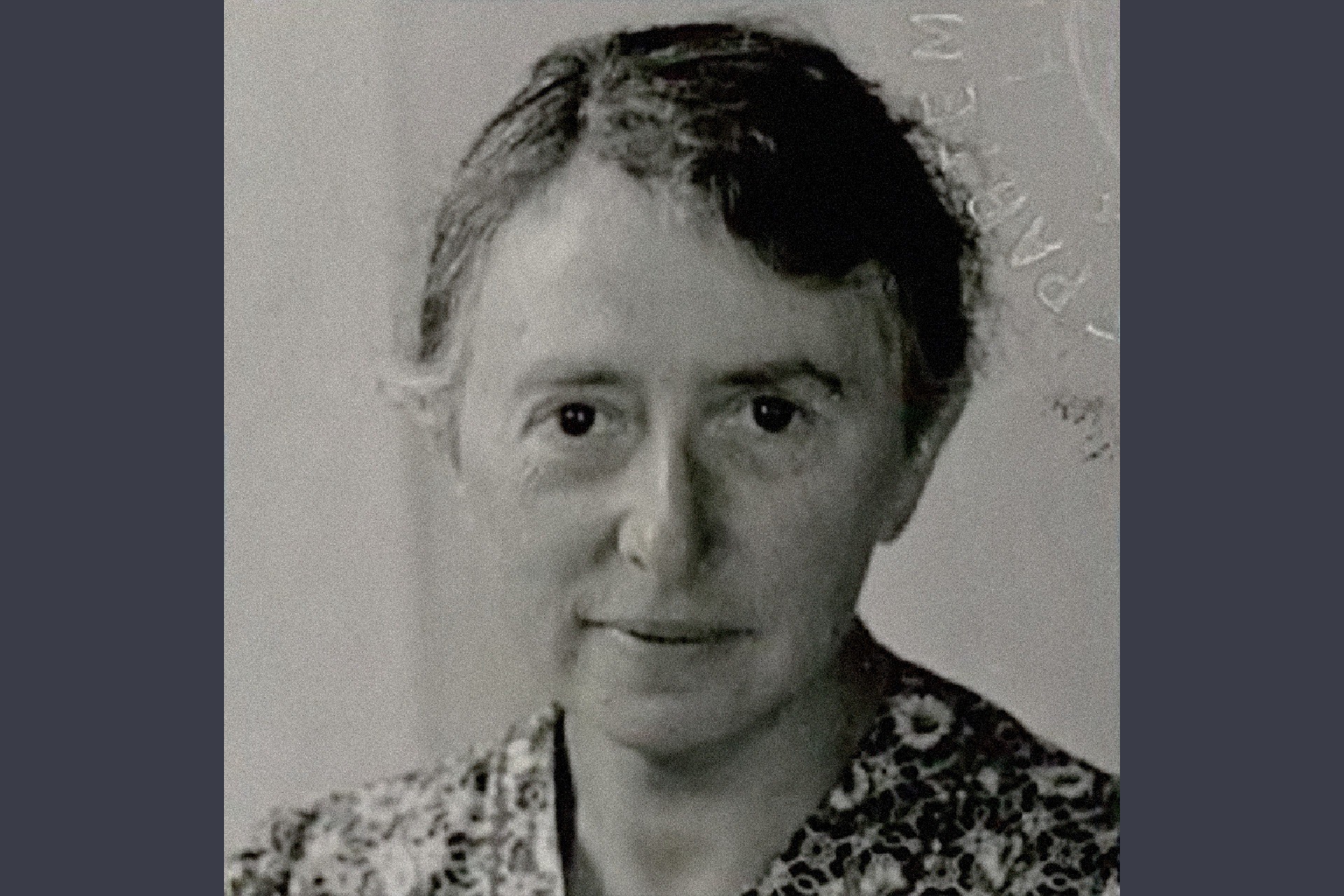

Elisabeth Frank> March 28, 1943

46 Elisabeth Frank

A summer in the Montafon: Elisabeth Frank's journey from Krefeld to Switzerland

Bludenz-Schruns-Bregenz-Höchst, March 28, 1943

On May 10, 1942, Elisabeth Amalia Frank stands at the train station in Bludenz and looks around. Where will she stay? Shortly after Easter, in mid-April 1942, she had received a summons to appear before the Gestapo in Krefeld. On March 6, her mother had died. Now her own life was at stake.

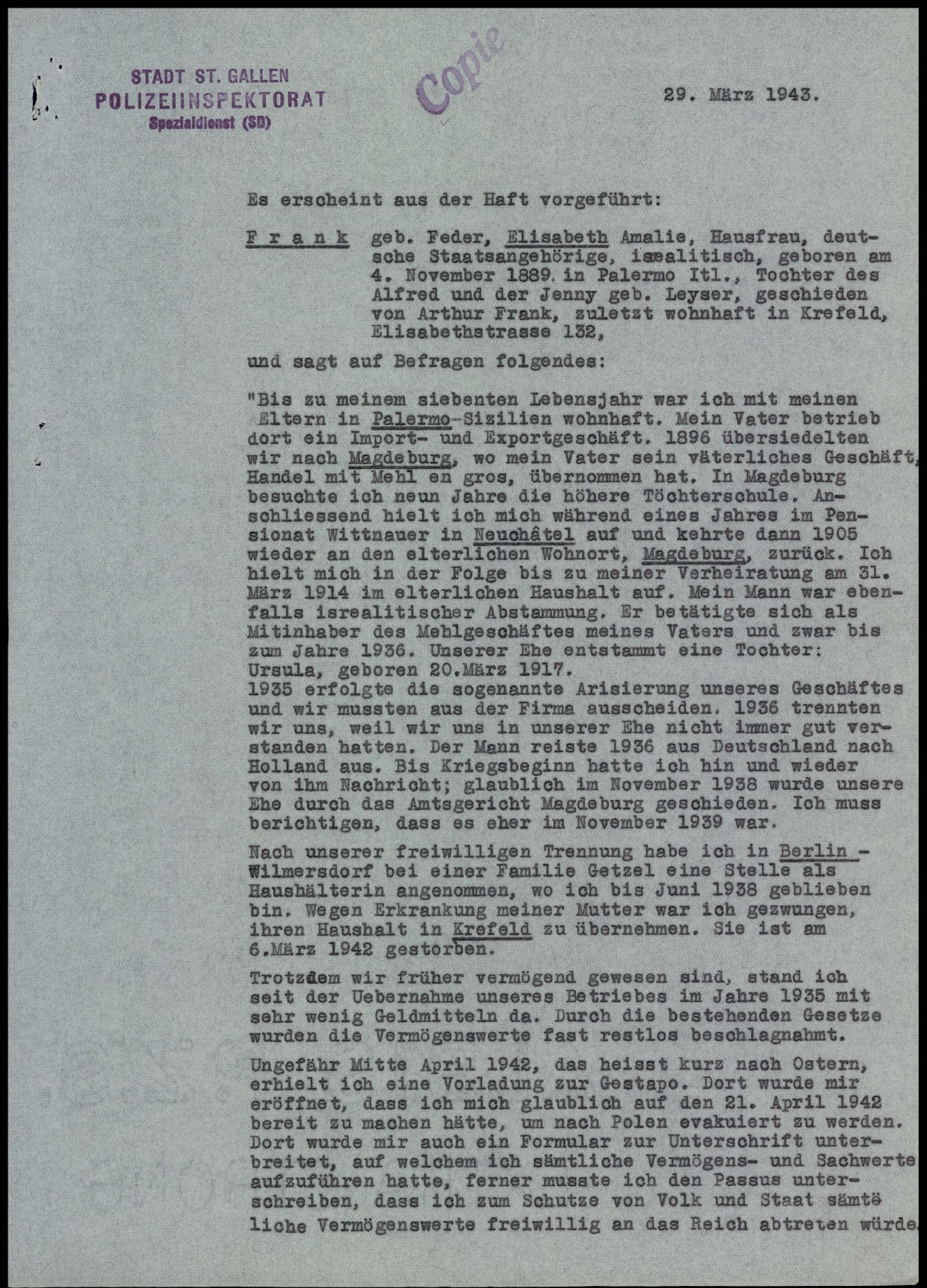

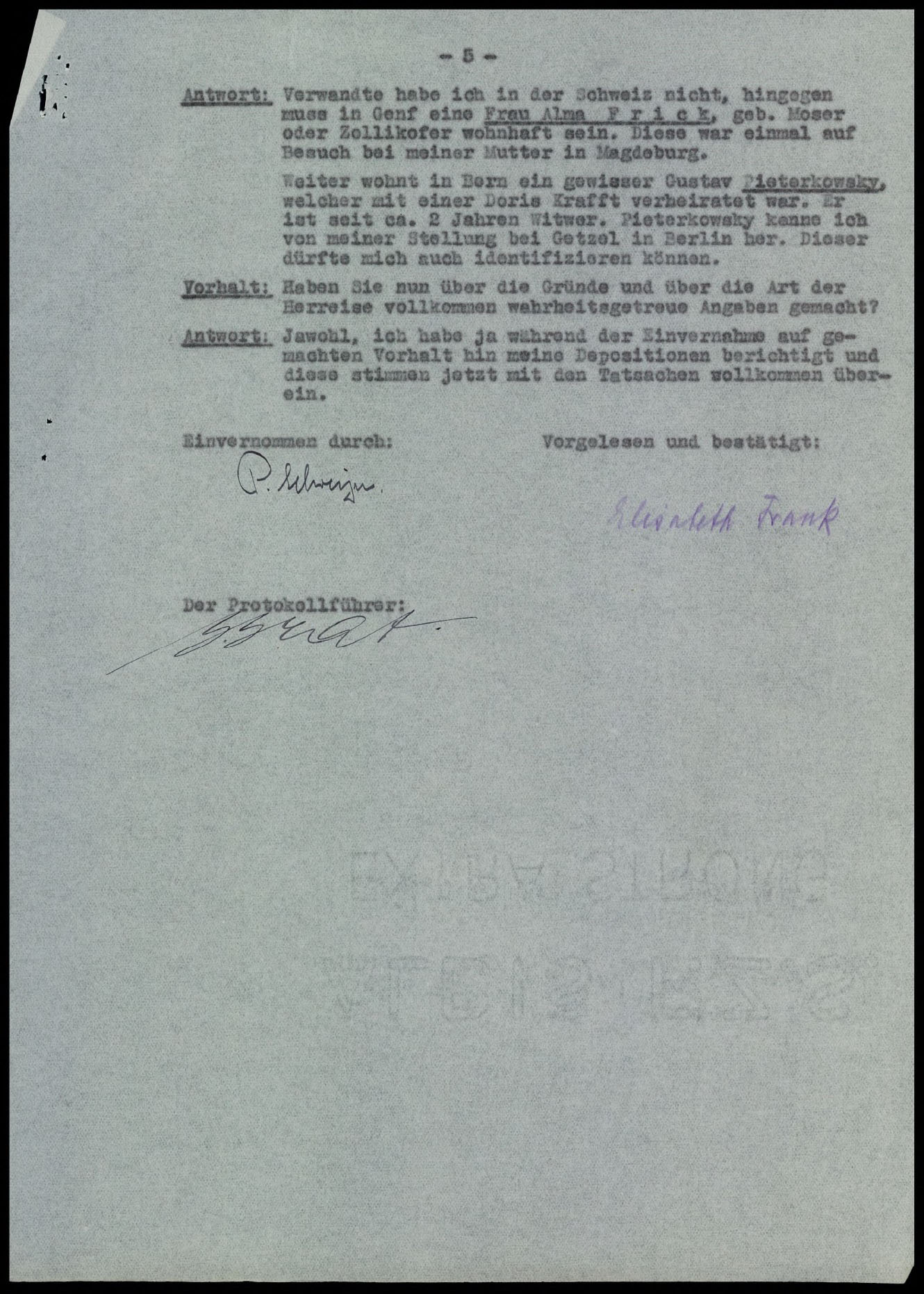

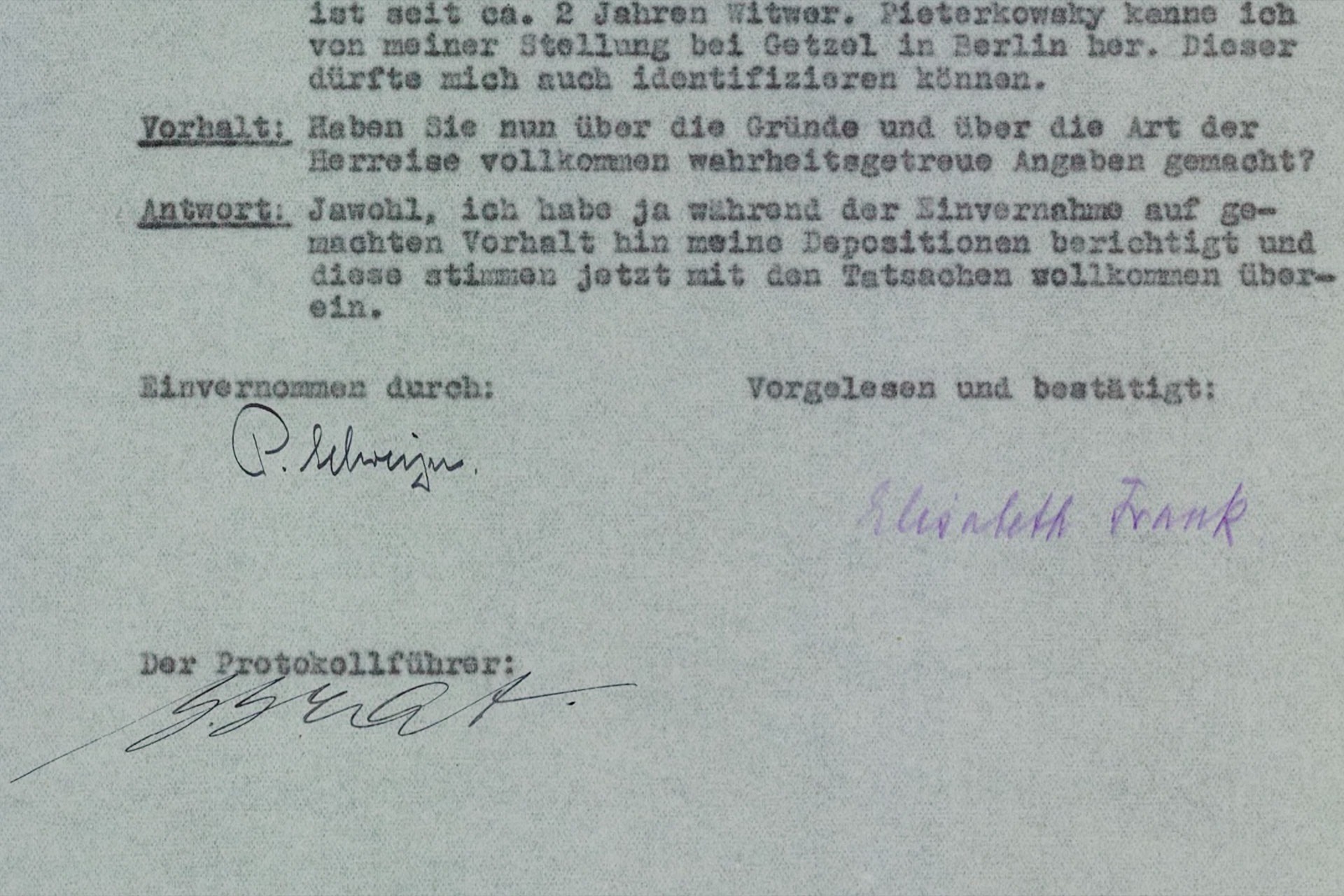

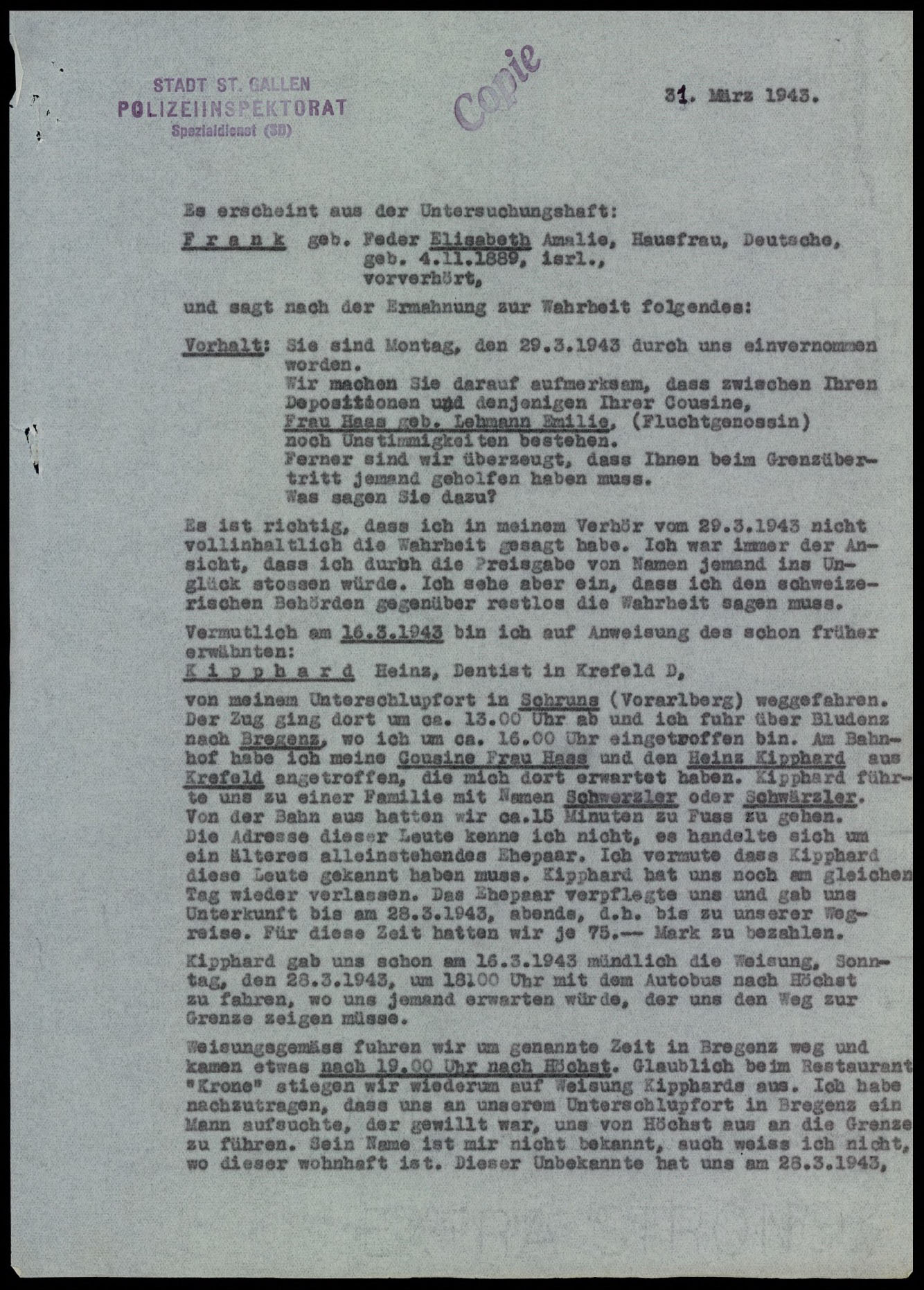

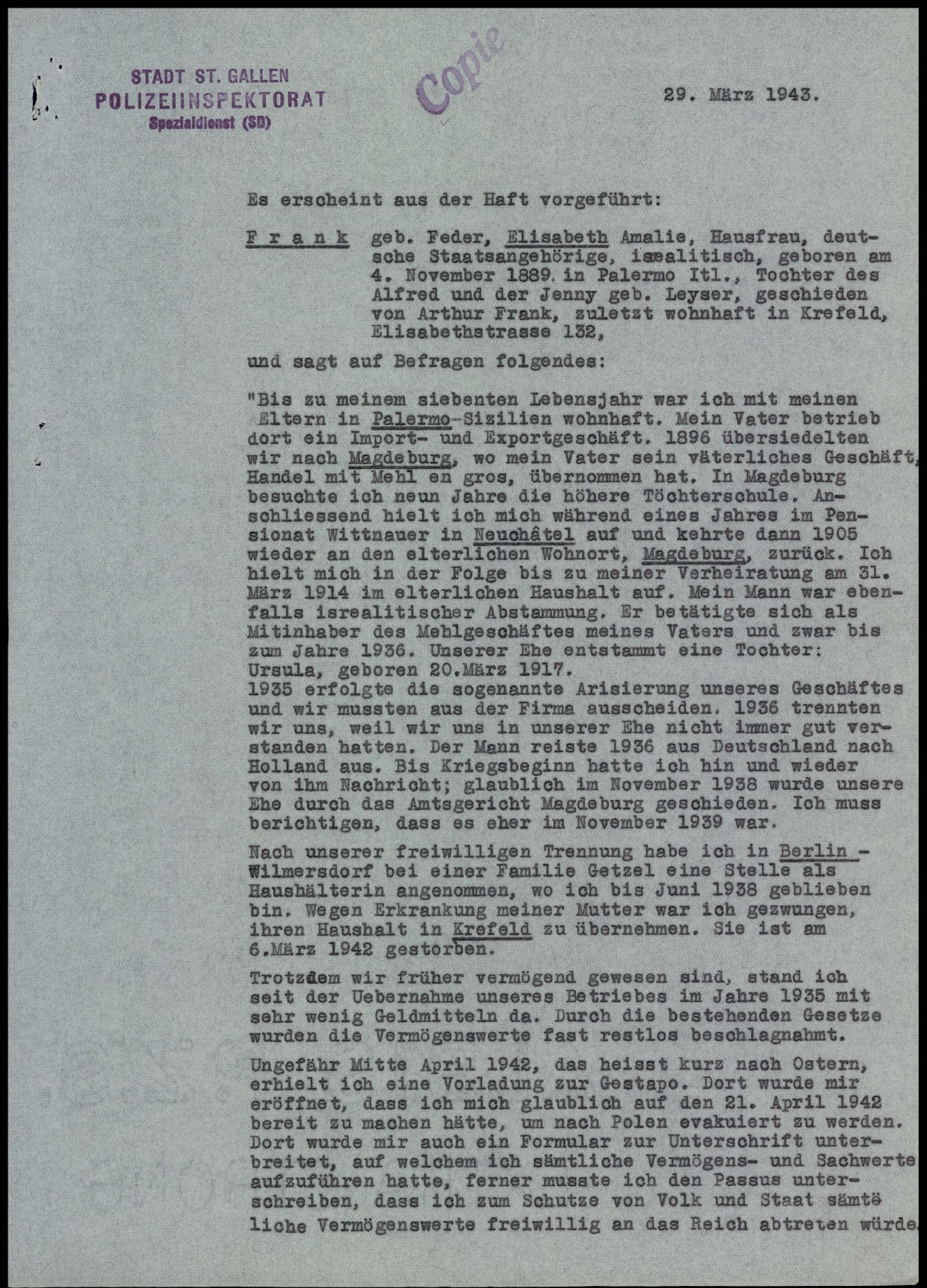

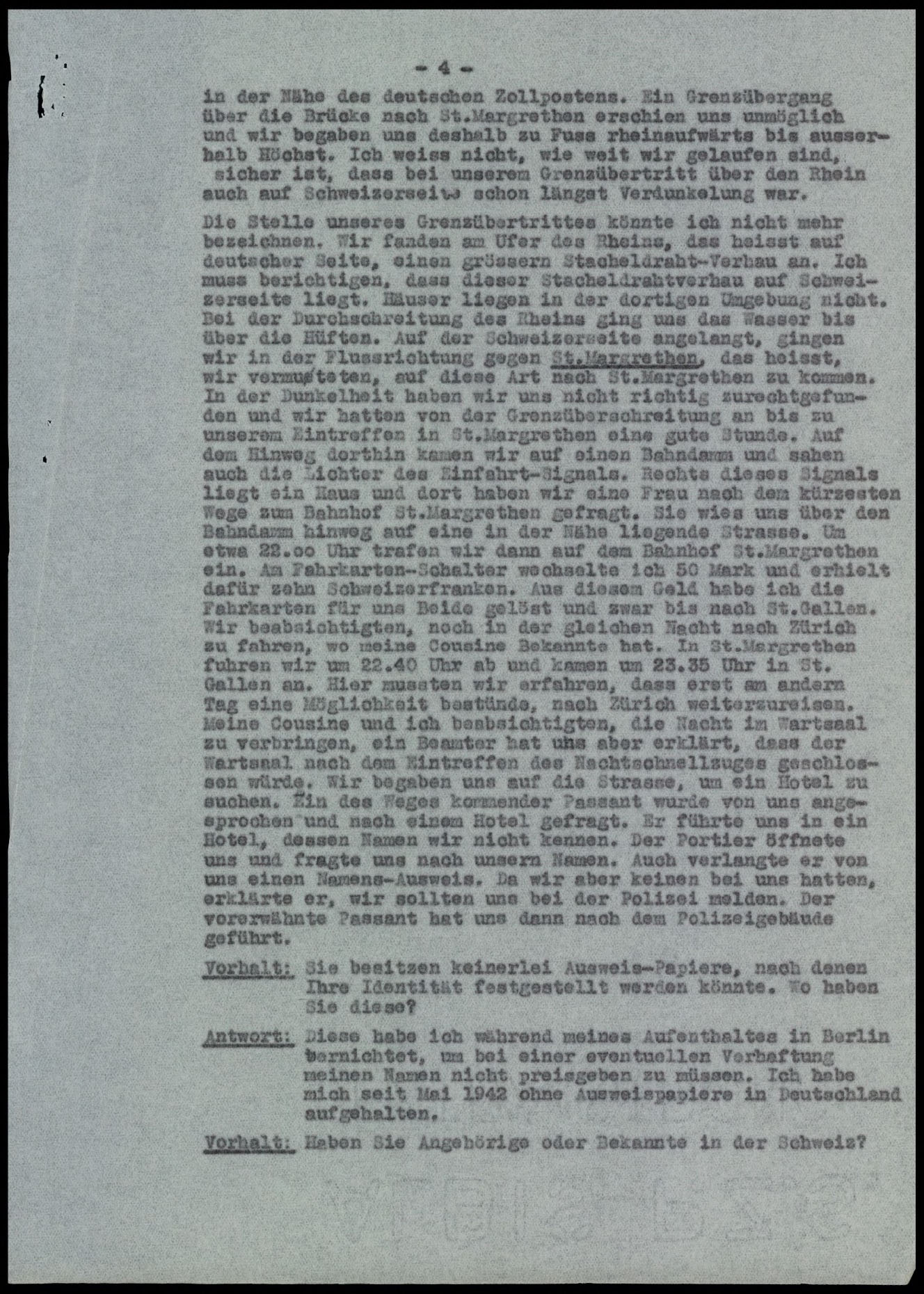

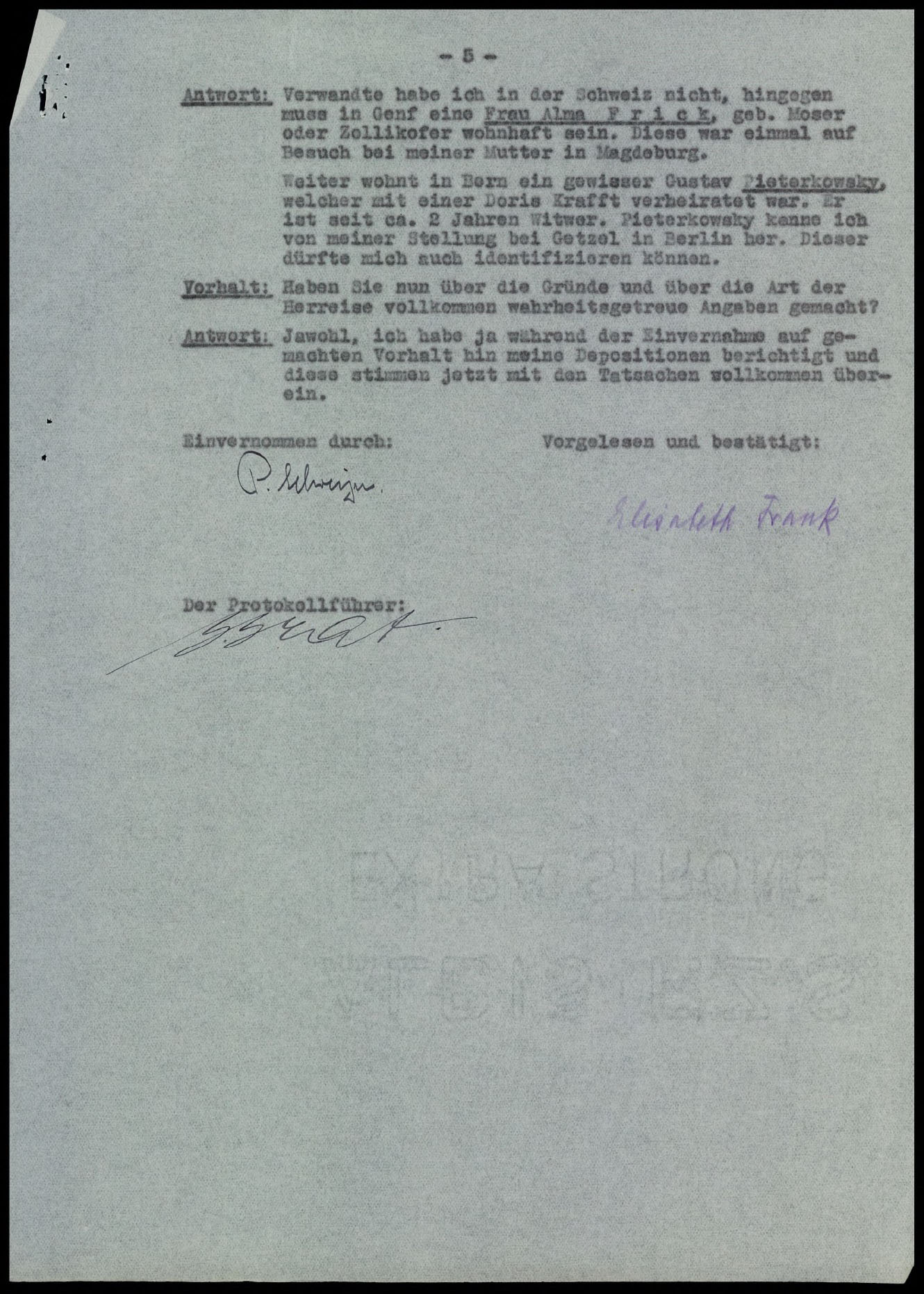

A year later, in March 1943, she would tell her story to the police in St. Gall, including her visit to the Gestapo.

“There it was opened to me that I would have to get ready to be evacuated to Poland on April 21, 1942, I think. There I was also given a form to sign, on which I had to list all assets and property, and I also had to sign the passage that I would voluntarily surrender all assets to the Reich for the protection of the people and the state. I was only allowed to pack a suitcase with some linen and clothes and to take 10 marks travel money with me.”[1]

Elisabeth Frank thinks of the transport to Lodz, to the Litzmannstadt ghetto. That is where the first Krefeld Jews were deported in October 1941.

“But we never heard from these people again. I was therefore in no way willing to be deported.”

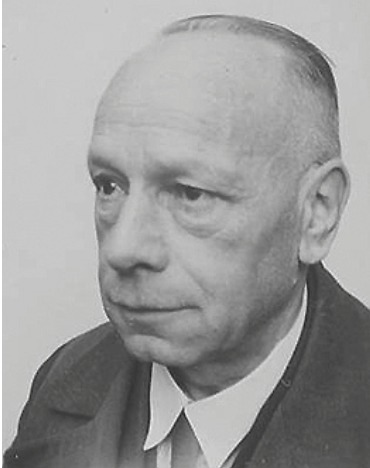

Elisabeth Frank is now 52 years old. She was born in Palermo, where her father ran an import-export business. When she was seven, the family moved to Magdeburg and took over her grandfather's flour business. Elisabeth attended the Höhere Töchterschule, a boarding school for girls in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, for a year. In 1914, she marries Arthur Frank and in 1917 their daughter Ursula is born. Four years later they have their child baptized. They want to fit in.

From 1936 on, the couple lives separately. Elisabeth moves in with her mother in Krefeld. Arthur Frank and the daughter emigrate to the Netherlands. But they continue to exchange cordial letters with each other. Even after the divorce is finalized in 1939.

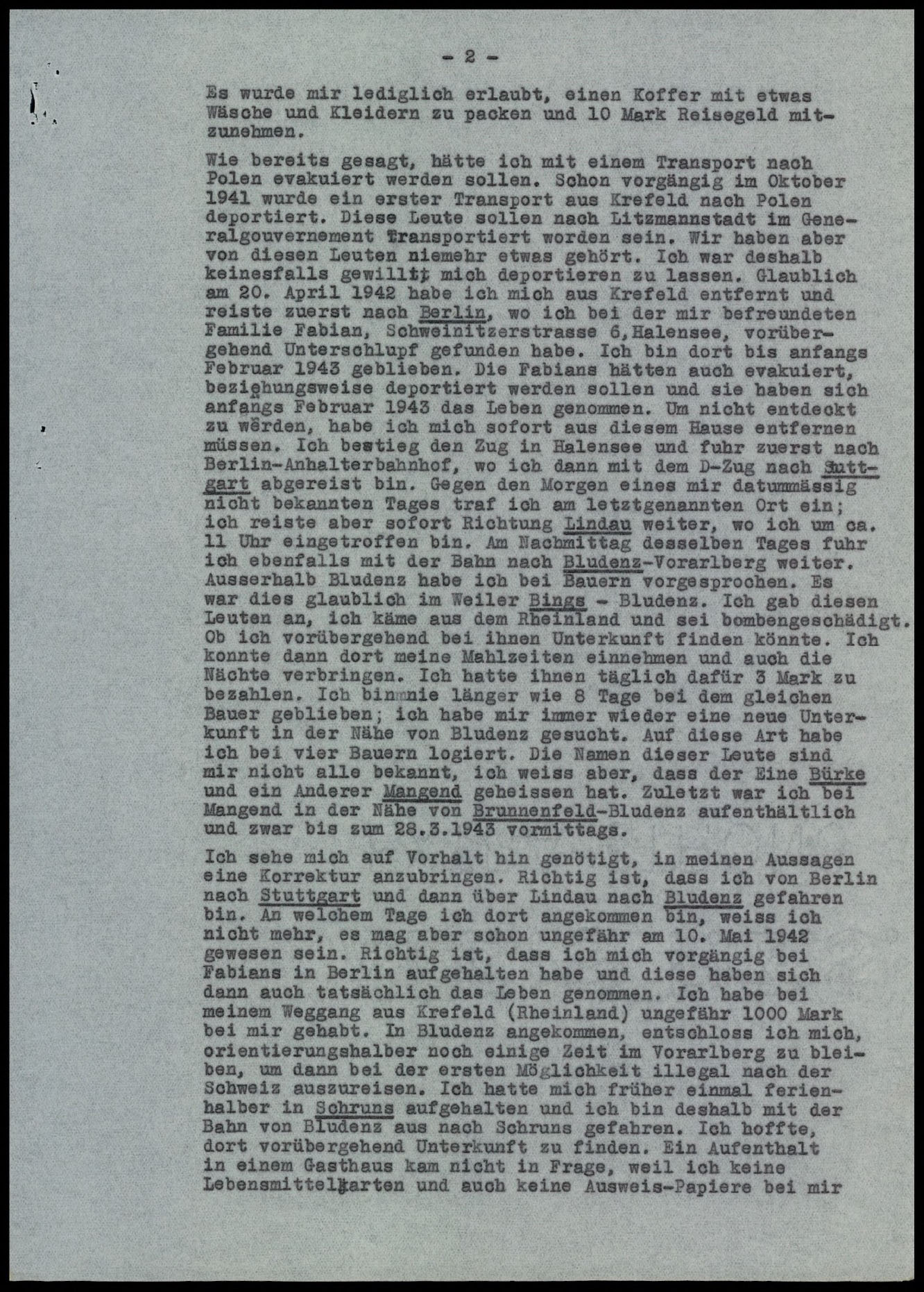

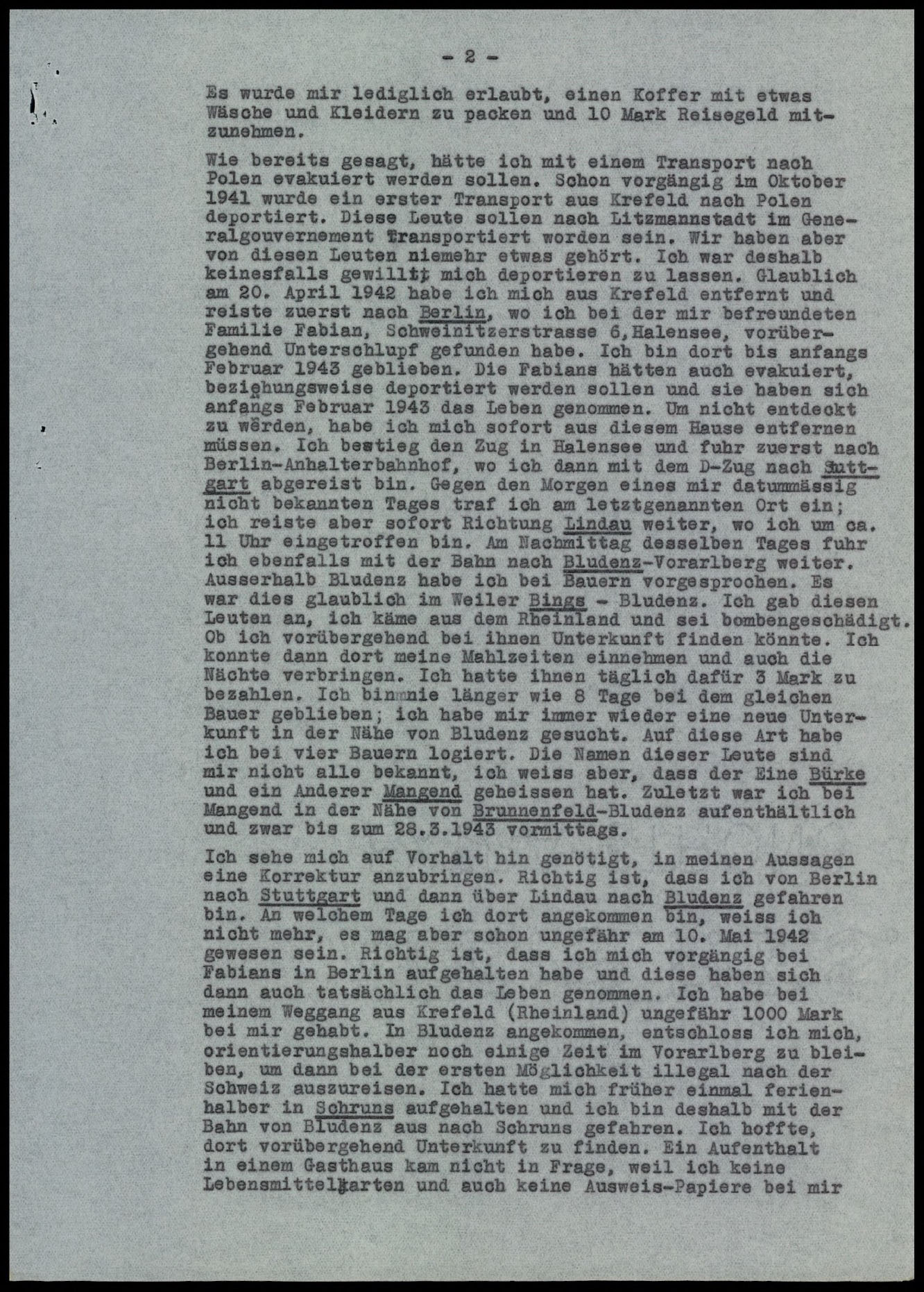

One day before her deportation, Elisabeth Frank manages to deceive the authorities. With the help of the dentist - and Social Democratic resistance fighter – Heinrich Kipphardt, she fakes her suicide to the authorities and flees first to Berlin to acquaintances, then from there on to Vorarlberg.

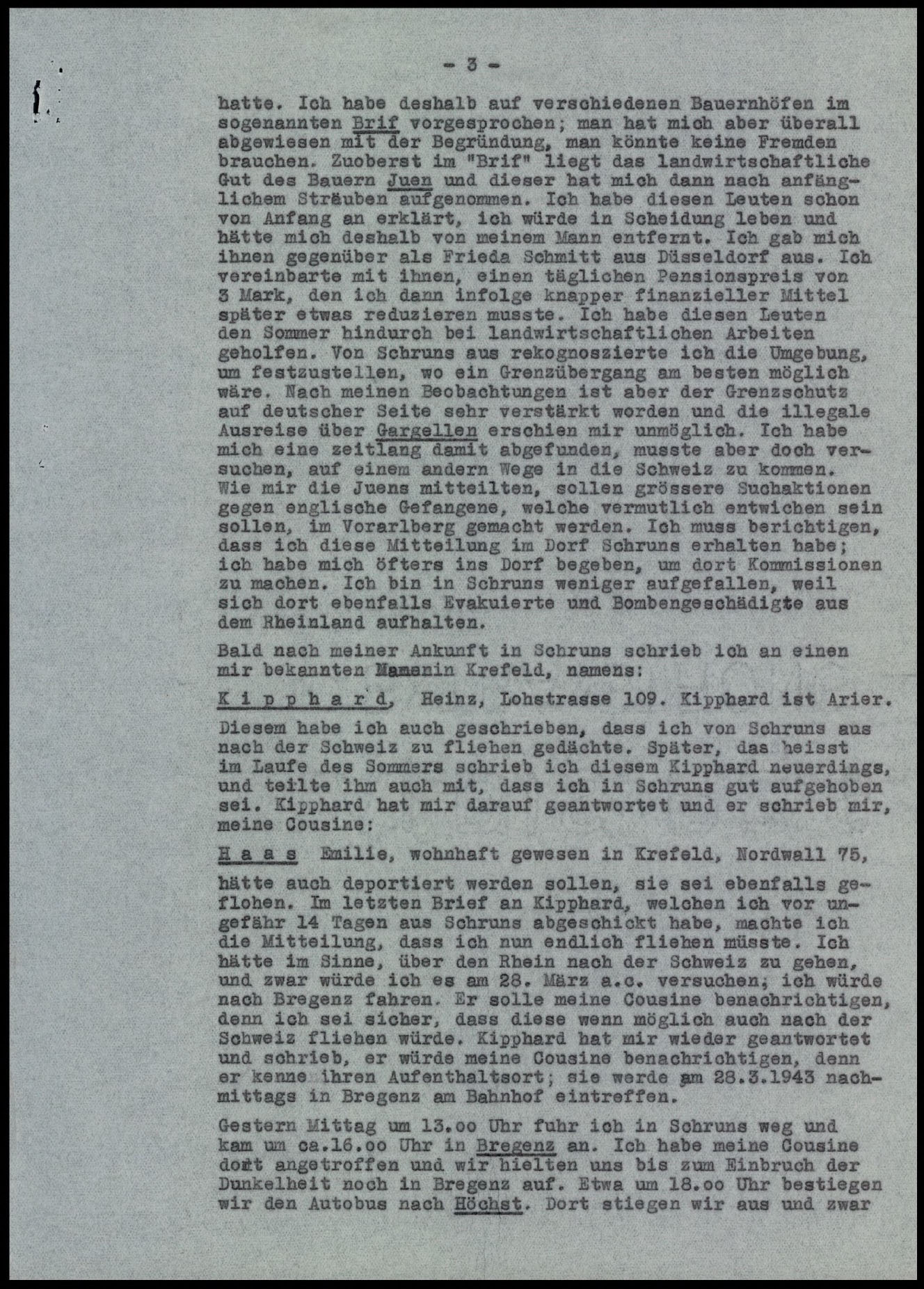

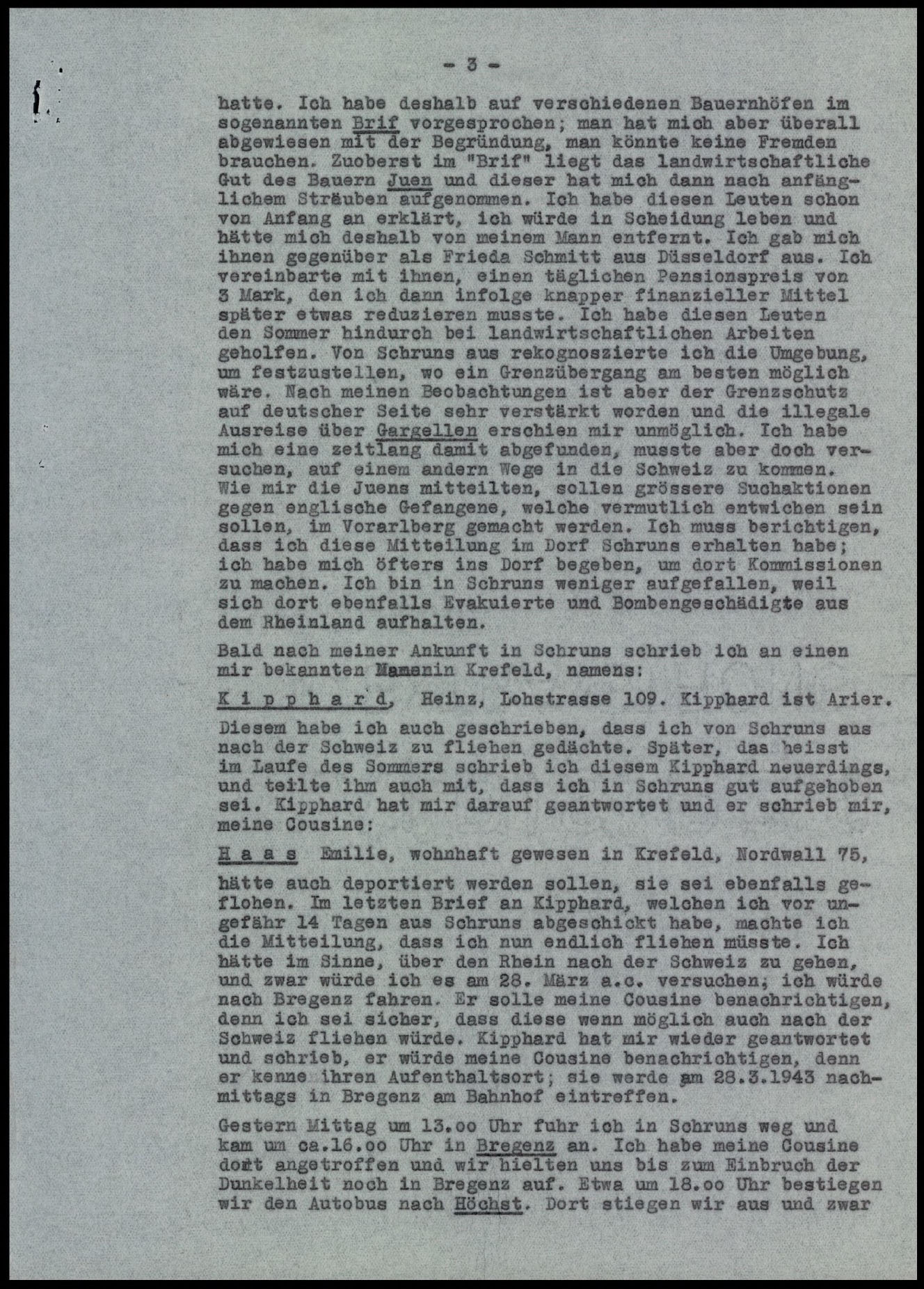

In Bludenz, she initially finds shelter with farmers in Bings and in Brunnenfeld. Later she will mention the names Bürkle and Mangeng. Then she lives with a farmer named Juen in Brif, a hamlet belonging to Schruns. She pretends to be a bombed-out woman named Frieda Schmitt from Düsseldorf. She still has some money with her, with which she can pay the farmers a boarding fee, then she makes herself useful as a harvest helper and explores the area for possibilities of escape. She does not dare to cross the border via Gargellen. Too many border guards are now on duty there.

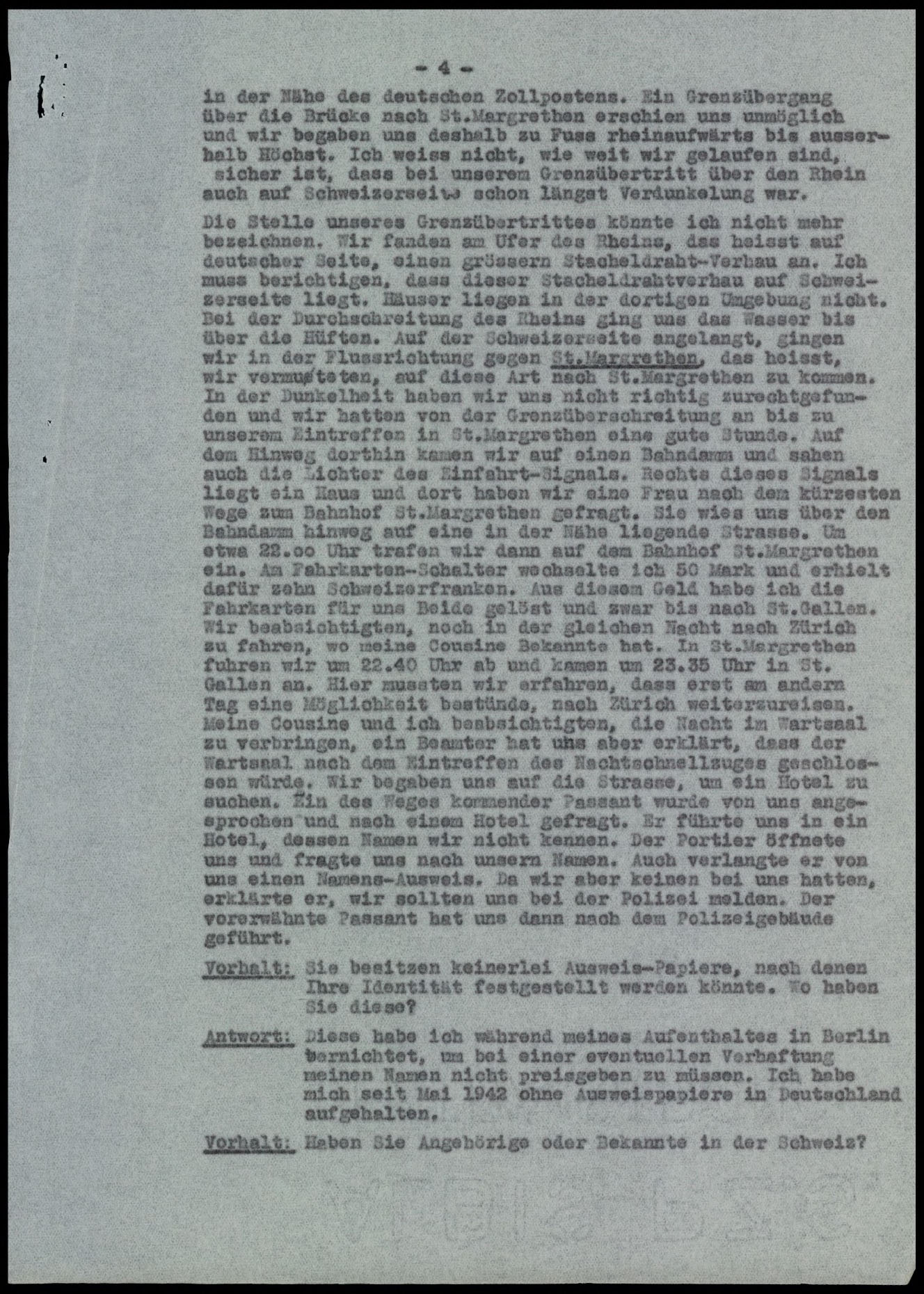

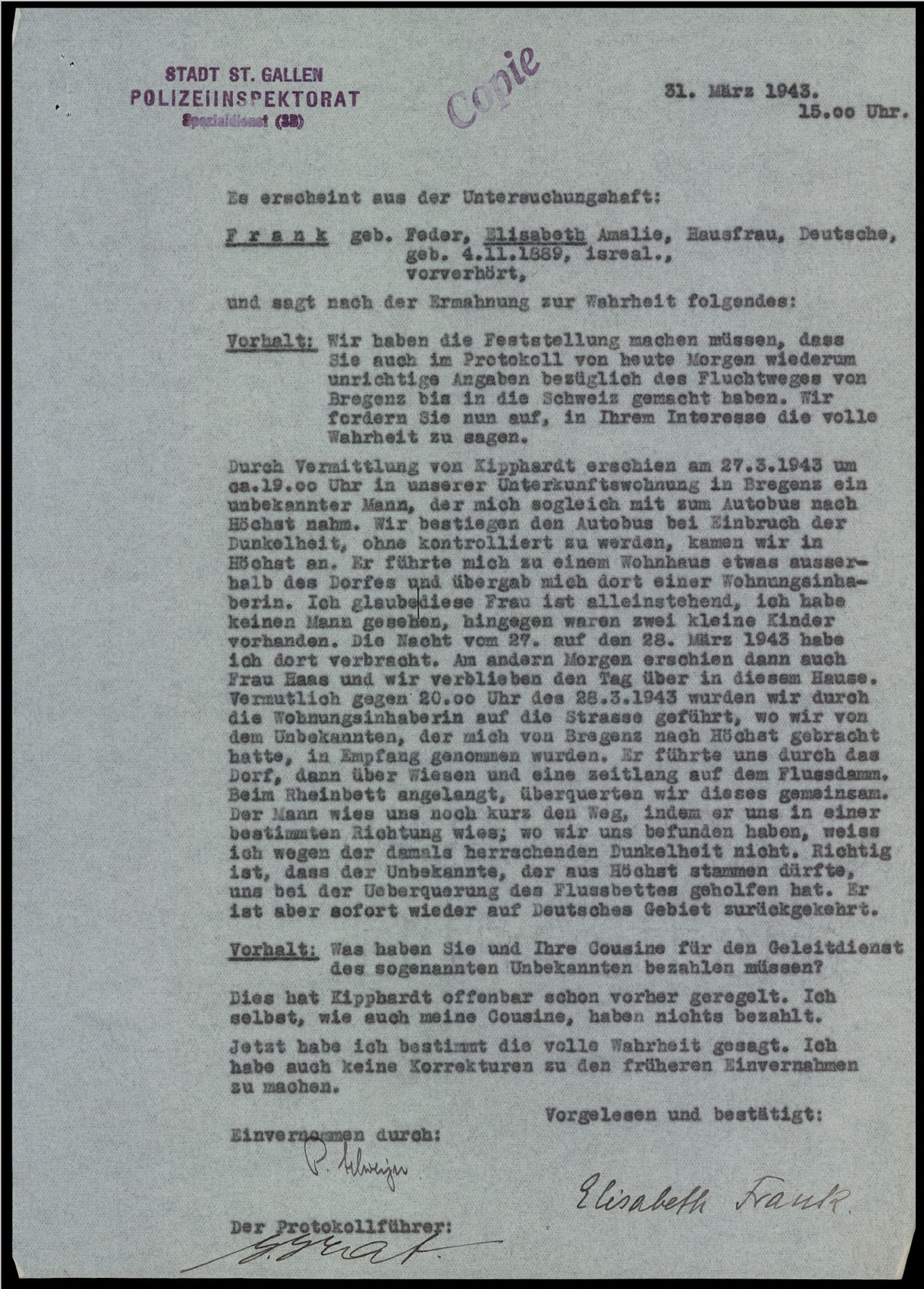

She is still in contact with Kipphardt. And in the meantime, he was also looking for a way to save her cousin, Emilie Haas. In mid-March 1943, the three of them meet in Bregenz. A family named Schwärzler takes in the two women for a few days, then on the evening of March 28 they set off from Höchst with the help of a smuggler of refugees across the Old Rhine to Switzerland.

The next morning, they are interrogated in St. Gall, and then twice more, as they get tangled up in contradictions so as not to reveal their helpers. Then the officials let it go. At the beginning of May, Elisabeth Frank is taken to the Oberhelfenschwil refugee camp. On May 25, the aliens police decide:

“The German citizen Elisabeth Amalie Frank, born November 4, 1889, crossed the Swiss border illegally as a refugee some time ago. Deportation is not feasible at present. (...) The above-named refugee will be interned until further notice.

The internment will be at her own expense, as far as means are available.”[2]

Elisabeth Frank tries to find a job as a domestic helper in order to be allowed to move into private accommodation. Her hopes are dashed several times. In the meantime, she suffers from nervous disorders. But then a woman in Kradolf in the canton of Thurgau takes her in. Elisabeth's sister Helene, who had managed to escape to Palestine, sends money from Haifa. In 1944, Elisabeth is able to move to Neuchâtel, where she had spent a year of her youth. She finds work, but still the immigration police try to get rid of her. In 1949, the Swiss embassy in Israel asks if she could be taken in by her sister. But in the same year the canton grants her the longed-for permanent asylum. In 1955, she dies in Neuchâtel. She never saw her daughter Ursula or her former husband again.

Ursula and Arthur Frank

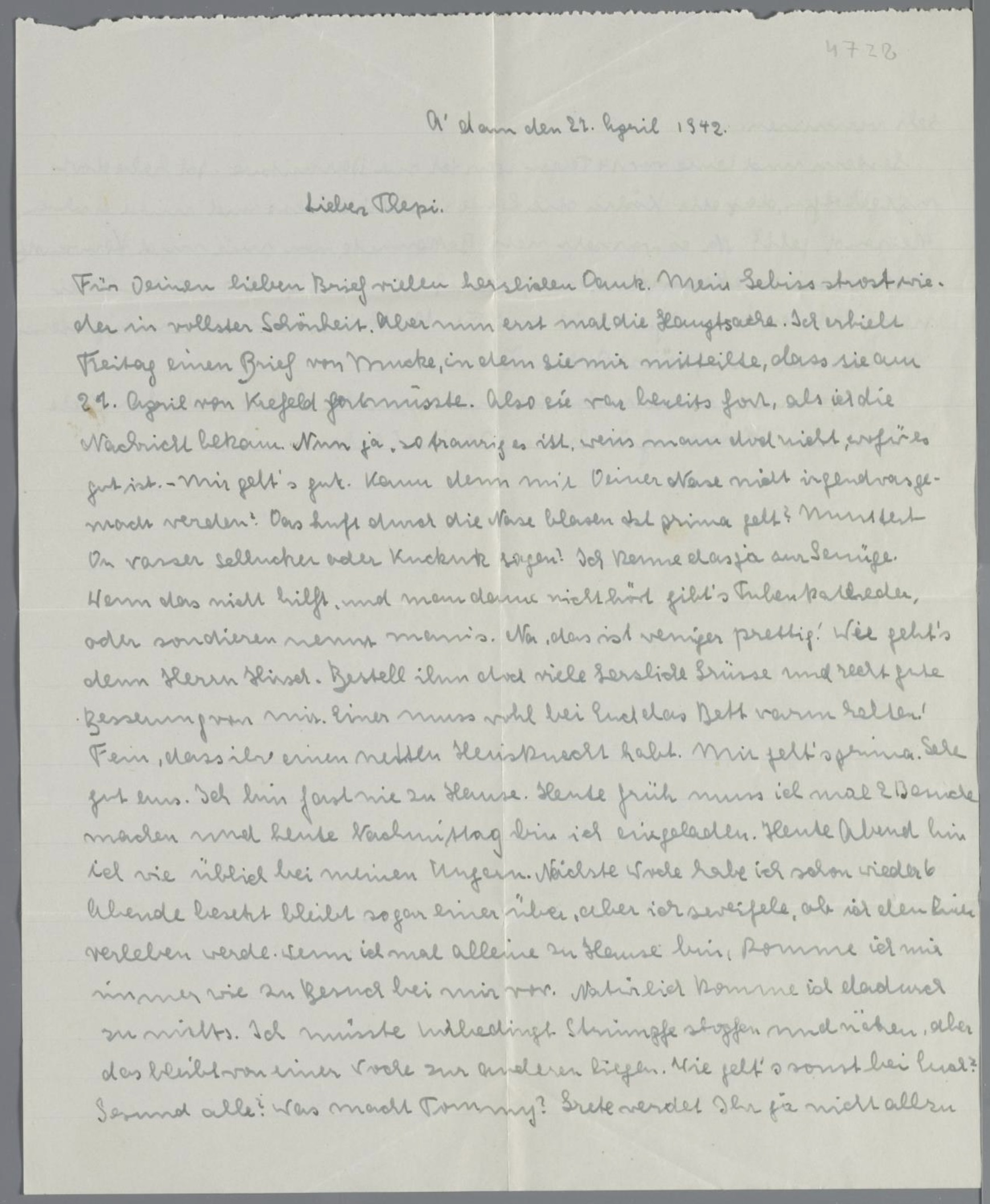

The last letters of her daughter Ursula Frank are kept in the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam. On April 23, 1942, she reports from Amsterdam to her father in Enschede that she received a note from her mother:

“I received a letter from Mucke on Friday, telling me that she had to leave Krefeld on April 21. (...) Well, sad as it is, you don't know what it's good for.”[3]

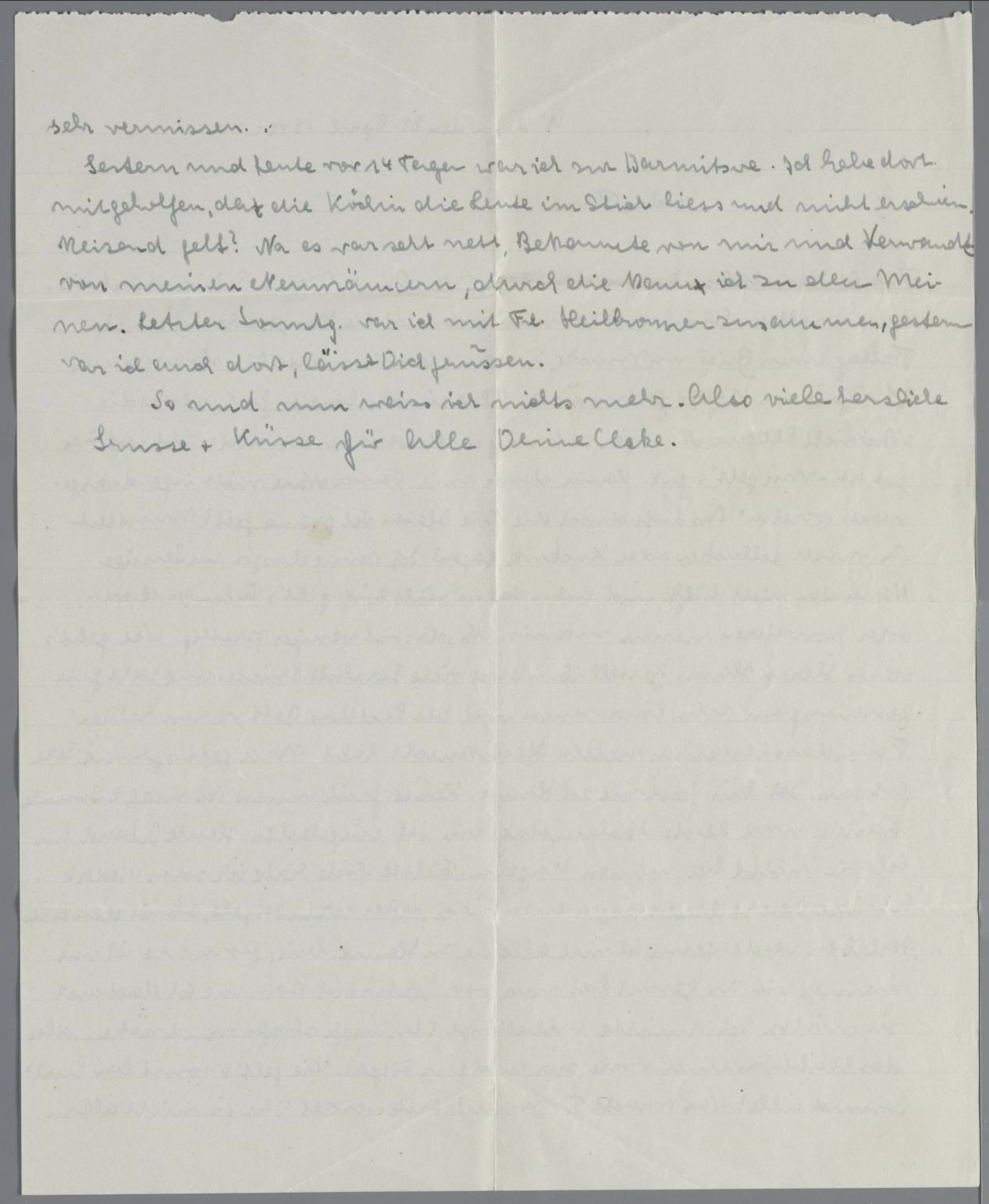

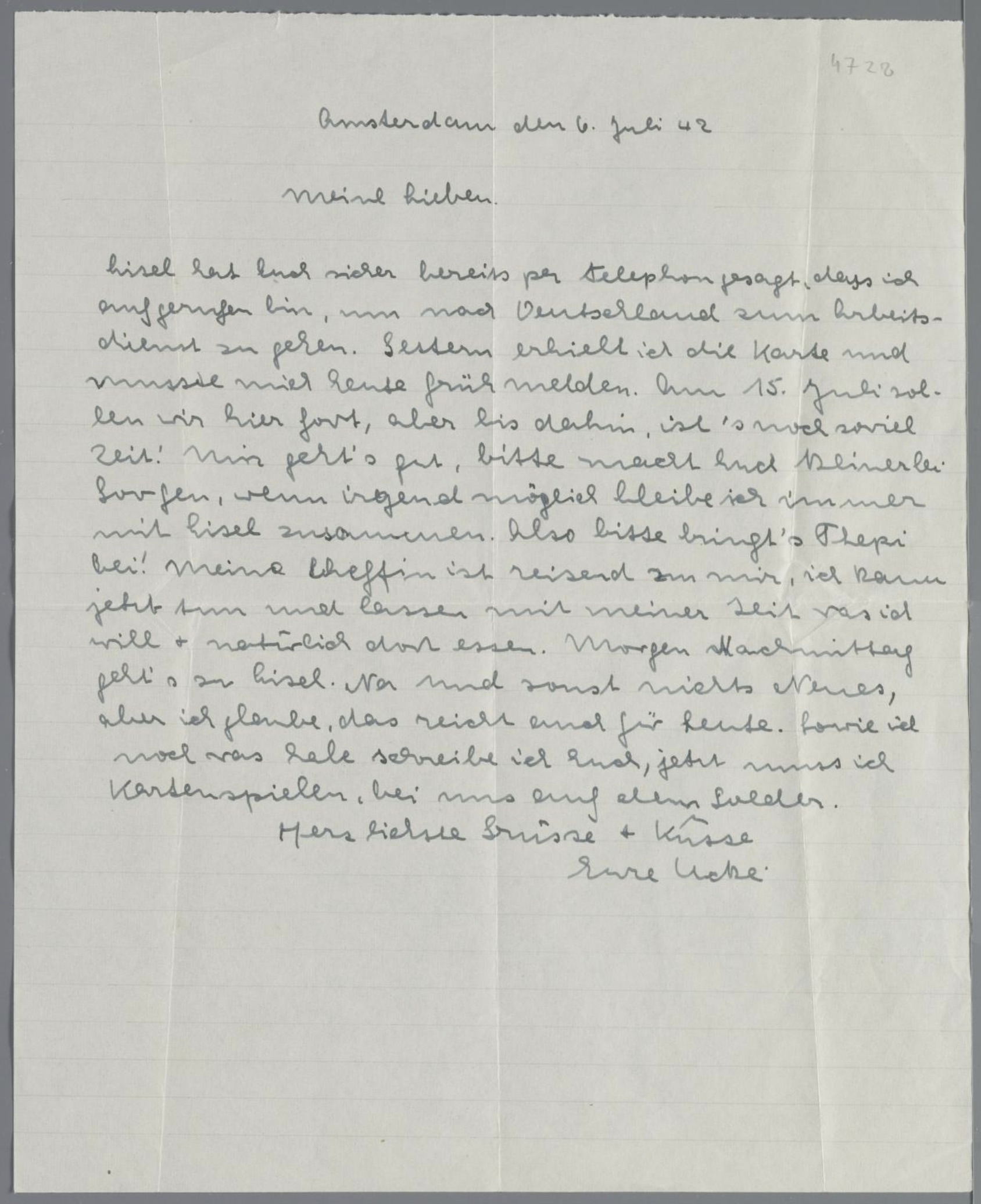

On July 7, she writes to friends and relatives:

“Lisel has surely already told you by telephone that I have been called to go to Germany now for labor service. (...) We are to leave here on July 15, but there is still so much time before then. I am fine, please do not worry, if at all possible I will always stay with Lisel. So please teach Thepi!”

Meanwhile, Thepi, her father, is trying everything to stop her deportation. He requests documents from Magdeburg proving her baptism and confirmation, believing that this will still make a difference to the Nazis.

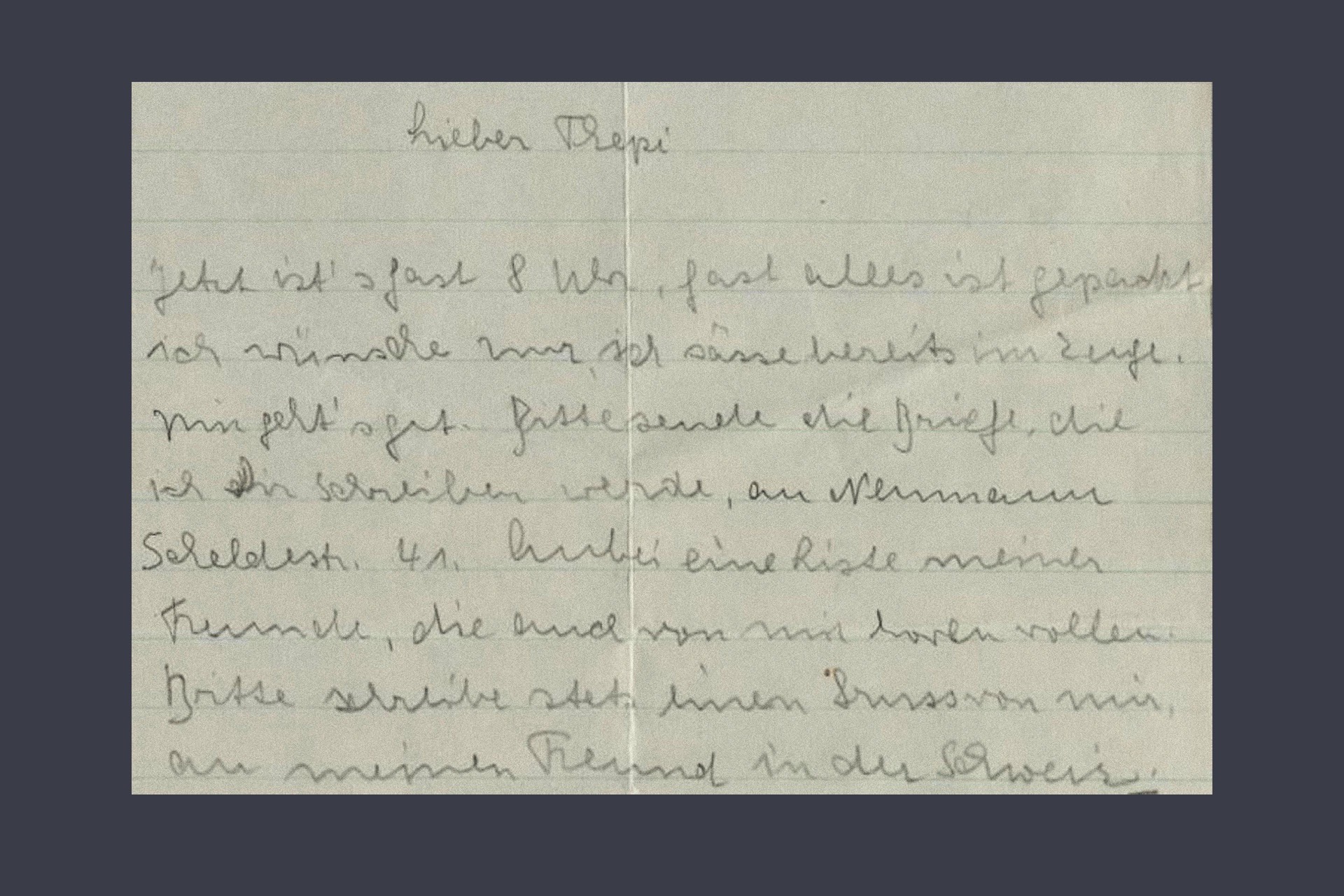

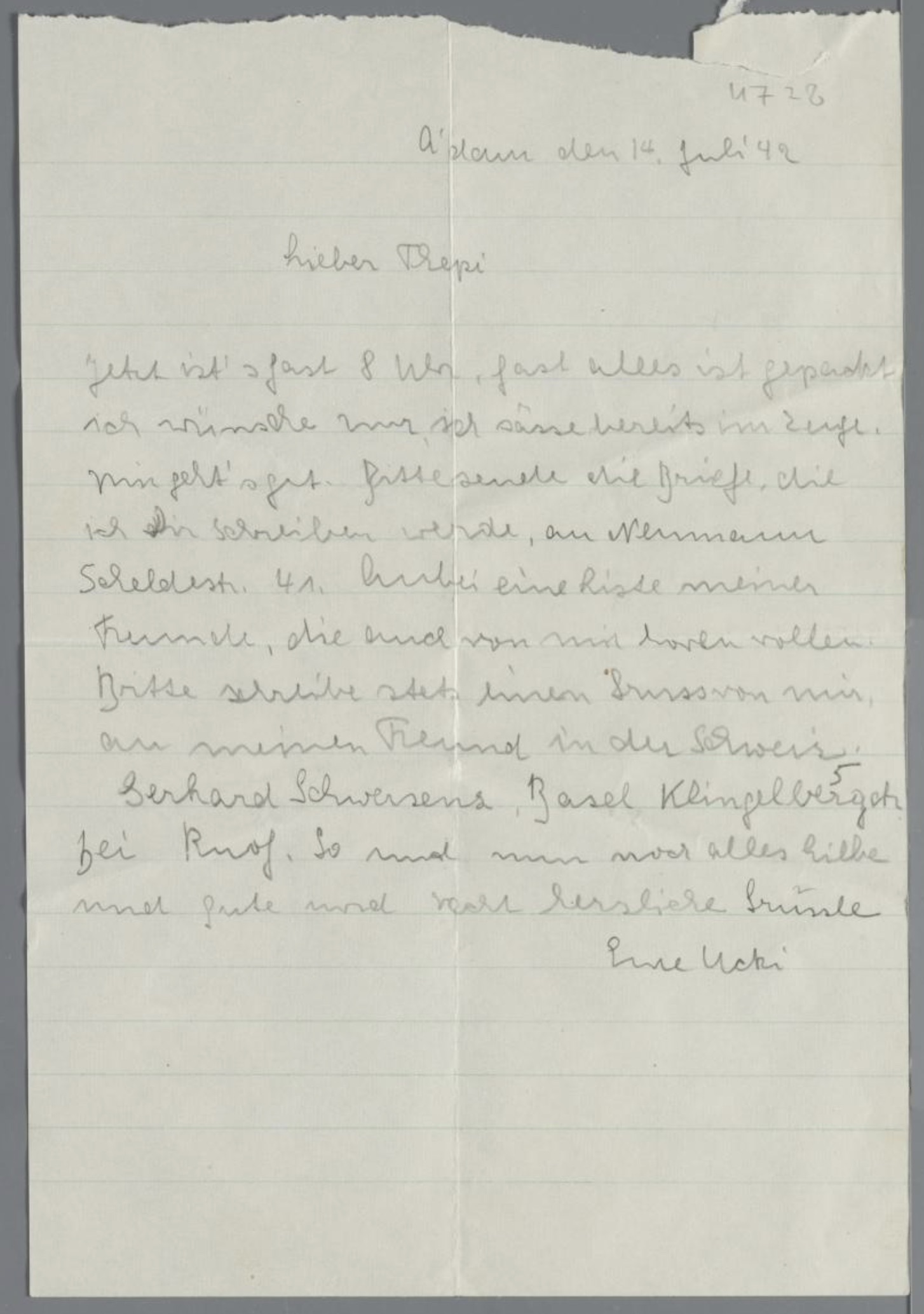

On July 14, she sends her last message to her father.

“Almost everything is packed. I only wish I were already on the train. I’m fine. (...) So and now all the best and best wishes, yours Ucki”.

On July 15, 1942, Ursula Frank was deported from the Westerbork camp near Amsterdam to Auschwitz. The date of her death in the camp is recorded as August 18, 1942. Her father follows her on September 3, 1944. Three days later he dies in the gas chambers of Birkenau.

[1] St. Gall Police Inspectorate, interrogation record Elisabeth Frank, March 29, 1943, Swiss Federal Archives, dossier Elisabeth Frank.

[2] Decision of the Police department of the Department of Justice and Police (Polizeiabteilung des Justiz- und Polizeidepartments), Bern, May 25, 1943, Swiss Federal Archives, dossier Elisabeth Frank.

[3] Letters of Ursula Frank to her father Arthur Frank and other relatives, Archive of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, D004728

St. Gall Police Inspectorate, 1st interrogation of Elisabeth Frank, March 29, 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Elisabeth Frank

St. Gall Police Inspectorate, 2nd interrogation of Elisabeth Frank, March 31, 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Elisabeth Frank

St. Gall Police Inspectorate, 3rd interrogation of Elisabeth Frank, March 31, 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Elisabeth Frank

Letter from Ursula Frank to Arthur Frank, April 22, 1942

Archive of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Letter from Ursula Frank, July 6, 1942

Archive of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Last letter from Ursula Frank to Arthur Frank, July 14, 1942

Archive of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

46 Elisabeth Frank

A summer in the Montafon: Elisabeth Frank's journey from Krefeld to Switzerland

Bludenz-Schruns-Bregenz-Höchst, March 28, 1943

On May 10, 1942, Elisabeth Amalia Frank stands at the train station in Bludenz and looks around. Where will she stay? Shortly after Easter, in mid-April 1942, she had received a summons to appear before the Gestapo in Krefeld. On March 6, her mother had died. Now her own life was at stake.

A year later, in March 1943, she would tell her story to the police in St. Gall, including her visit to the Gestapo.

“There it was opened to me that I would have to get ready to be evacuated to Poland on April 21, 1942, I think. There I was also given a form to sign, on which I had to list all assets and property, and I also had to sign the passage that I would voluntarily surrender all assets to the Reich for the protection of the people and the state. I was only allowed to pack a suitcase with some linen and clothes and to take 10 marks travel money with me.”[1]

Elisabeth Frank thinks of the transport to Lodz, to the Litzmannstadt ghetto. That is where the first Krefeld Jews were deported in October 1941.

“But we never heard from these people again. I was therefore in no way willing to be deported.”

Elisabeth Frank is now 52 years old. She was born in Palermo, where her father ran an import-export business. When she was seven, the family moved to Magdeburg and took over her grandfather's flour business. Elisabeth attended the Höhere Töchterschule, a boarding school for girls in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, for a year. In 1914, she marries Arthur Frank and in 1917 their daughter Ursula is born. Four years later they have their child baptized. They want to fit in.

From 1936 on, the couple lives separately. Elisabeth moves in with her mother in Krefeld. Arthur Frank and the daughter emigrate to the Netherlands. But they continue to exchange cordial letters with each other. Even after the divorce is finalized in 1939.

One day before her deportation, Elisabeth Frank manages to deceive the authorities. With the help of the dentist - and Social Democratic resistance fighter – Heinrich Kipphardt, she fakes her suicide to the authorities and flees first to Berlin to acquaintances, then from there on to Vorarlberg.

In Bludenz, she initially finds shelter with farmers in Bings and in Brunnenfeld. Later she will mention the names Bürkle and Mangeng. Then she lives with a farmer named Juen in Brif, a hamlet belonging to Schruns. She pretends to be a bombed-out woman named Frieda Schmitt from Düsseldorf. She still has some money with her, with which she can pay the farmers a boarding fee, then she makes herself useful as a harvest helper and explores the area for possibilities of escape. She does not dare to cross the border via Gargellen. Too many border guards are now on duty there.

She is still in contact with Kipphardt. And in the meantime, he was also looking for a way to save her cousin, Emilie Haas. In mid-March 1943, the three of them meet in Bregenz. A family named Schwärzler takes in the two women for a few days, then on the evening of March 28 they set off from Höchst with the help of a smuggler of refugees across the Old Rhine to Switzerland.

The next morning, they are interrogated in St. Gall, and then twice more, as they get tangled up in contradictions so as not to reveal their helpers. Then the officials let it go. At the beginning of May, Elisabeth Frank is taken to the Oberhelfenschwil refugee camp. On May 25, the aliens police decide:

“The German citizen Elisabeth Amalie Frank, born November 4, 1889, crossed the Swiss border illegally as a refugee some time ago. Deportation is not feasible at present. (...) The above-named refugee will be interned until further notice.

The internment will be at her own expense, as far as means are available.”[2]

Elisabeth Frank tries to find a job as a domestic helper in order to be allowed to move into private accommodation. Her hopes are dashed several times. In the meantime, she suffers from nervous disorders. But then a woman in Kradolf in the canton of Thurgau takes her in. Elisabeth's sister Helene, who had managed to escape to Palestine, sends money from Haifa. In 1944, Elisabeth is able to move to Neuchâtel, where she had spent a year of her youth. She finds work, but still the immigration police try to get rid of her. In 1949, the Swiss embassy in Israel asks if she could be taken in by her sister. But in the same year the canton grants her the longed-for permanent asylum. In 1955, she dies in Neuchâtel. She never saw her daughter Ursula or her former husband again.

Ursula and Arthur Frank

The last letters of her daughter Ursula Frank are kept in the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam. On April 23, 1942, she reports from Amsterdam to her father in Enschede that she received a note from her mother:

“I received a letter from Mucke on Friday, telling me that she had to leave Krefeld on April 21. (...) Well, sad as it is, you don't know what it's good for.”[3]

On July 7, she writes to friends and relatives:

“Lisel has surely already told you by telephone that I have been called to go to Germany now for labor service. (...) We are to leave here on July 15, but there is still so much time before then. I am fine, please do not worry, if at all possible I will always stay with Lisel. So please teach Thepi!”

Meanwhile, Thepi, her father, is trying everything to stop her deportation. He requests documents from Magdeburg proving her baptism and confirmation, believing that this will still make a difference to the Nazis.

On July 14, she sends her last message to her father.

“Almost everything is packed. I only wish I were already on the train. I’m fine. (...) So and now all the best and best wishes, yours Ucki”.

On July 15, 1942, Ursula Frank was deported from the Westerbork camp near Amsterdam to Auschwitz. The date of her death in the camp is recorded as August 18, 1942. Her father follows her on September 3, 1944. Three days later he dies in the gas chambers of Birkenau.

[1] St. Gall Police Inspectorate, interrogation record Elisabeth Frank, March 29, 1943, Swiss Federal Archives, dossier Elisabeth Frank.

[2] Decision of the Police department of the Department of Justice and Police (Polizeiabteilung des Justiz- und Polizeidepartments), Bern, May 25, 1943, Swiss Federal Archives, dossier Elisabeth Frank.

[3] Letters of Ursula Frank to her father Arthur Frank and other relatives, Archive of the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, D004728