Ernst Eisenmayer> September 1938

47 Ernst Eisenmayer

Ernst Eisenmayer almost made it, but Swiss police sends him back

Drusentor, September 1938

“Two of my Jewish schoolmates had managed to get into Switzerland in time, before the Swiss virtually closed the border for us. But we were getting desperate. Some of our Nazi schoolmates had warned us, if any warning was needed, that things were likely to get worse for us. And we tried to find a way to leave. We went from embassy to embassy of all corners of the world. The answer was always: NO. No money, no ‘proper’ papers, what did we expect? (…)

I had kept in touch with the two friends, who had managed to get to Zurich. They suggested I should try to climb over a rather difficult mountain on the border, the Rhaetikon range and to get into Switzerland that way. It seemed a fair idea. We had nothing to lose, or so we thought, the two of us trying to get away from ‘them’.”[1]

Together with a relative of the same age, a distant cousin named Hans Reisz, seventeen-year-old Ernst Eisenmayer planned his escape in Vienna in the late summer of 1938. They would pose as hikers.

Many years later, Ernst Eisenmayer writes down his memories in England. Some of the details are enigmatic. Memories are not always a reliable friend. How they reached their destination is unclear.

“We travelled through the night to the Western part of Austria, but left the train well before the border, not to arouse any suspicion. There were lots of police and uniformed characters about amid the flags. You could have called it colourful. Then we took the local bus up one valley and stayed the night at a small inn. The village had streamers across the road, then almost compulsory, of ‘Jews are not welcome here’. We had to take chance.”[2]

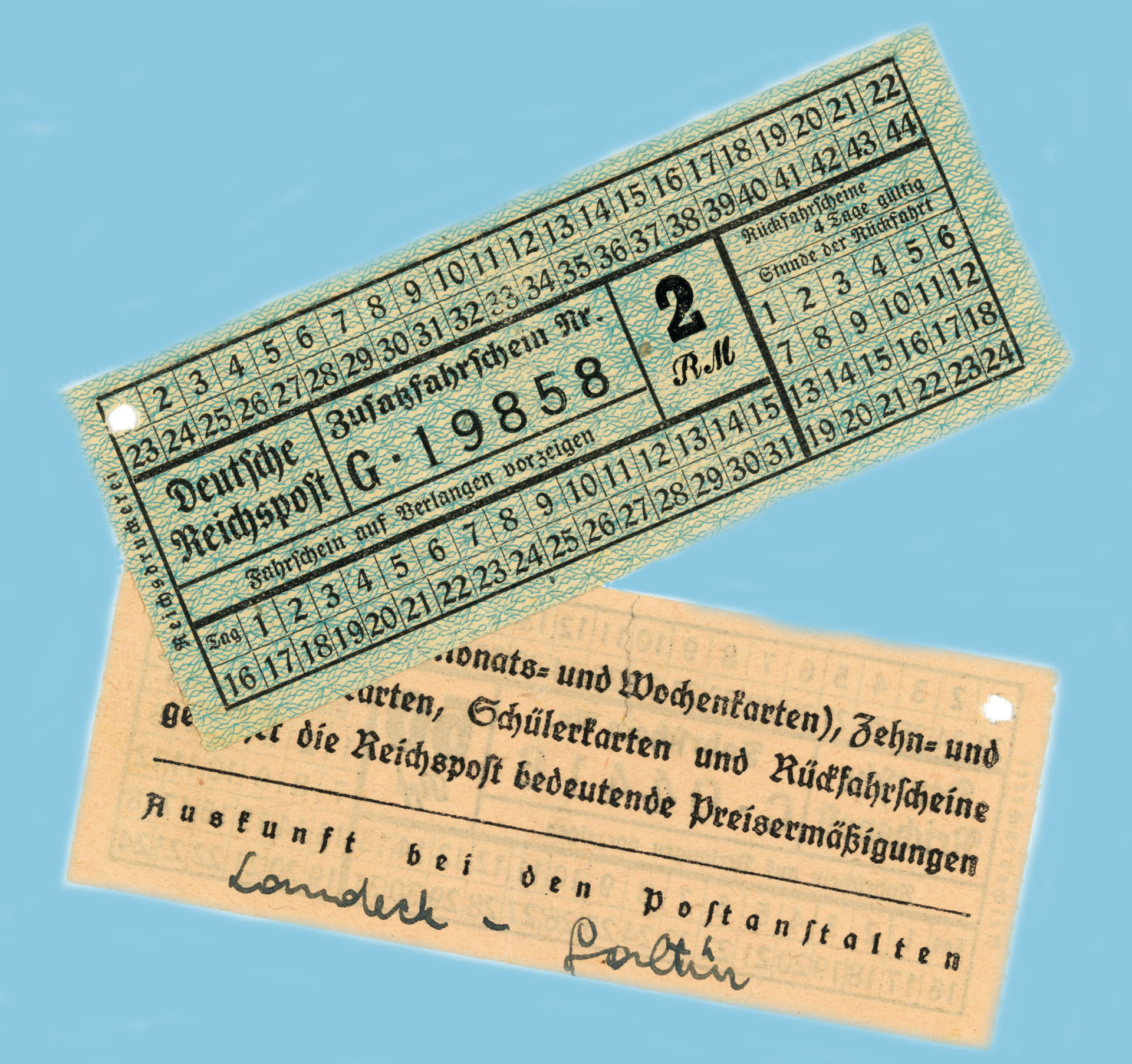

Eisenmayer has kept a bus ticket from this trip, but it shows Galtür as the destination. He remembers that they hiked for a whole day, over to another valley, then spent the night outdoors. In the early morning they set off again. His dramatic description turns the escape into an exciting adventure.

“There was just enough light to read the map, to make sure of the lay of the land. My limited mountaineering experience came in handy. My cousin had never been any higher than a thousand meters on a mountain near Vienna. He wasn’t the sporty kind.

We were still below the tree line and I have worked out a route to the border. We had arranged to mee our ‘Swiss’ friends on the south side of the Sulzfluh range. We had arranged all details by post and they were coming very much to life that day. Perilous looking rock faces were beginning to get lit up by the rising sun, gloriously beautiful to look at, taking our breath away thinking about the climb ahead.

‚Do we have to get across there?’ asked my cousin already panting a little, as we were approaching the glacier.

‘Yes, that’s the one. And our two pals will be waiting for us the other side!’

I answered to encourage myself and him without the least thought of turning back. Although I began to realize, that it was going to be far from easy.”[3]

On the other side of the mountain, so Eisenmayer in his recollections, they actually meet the friends. A photo shows the two fugitives taking a rest, the Sulzfluh seen from the south in the background. But Eisenmayer's escape story does not end there. At the train station down in the valley, they are stopped by the police. Instead of being able to board the train to Zurich, they are interrogated - and eventually deported back to the German Reich. And sent back to Vienna. Eisenmayer attempted to escape once again a few weeks later, across the border into France. And after the November pogrom, he finds himself in Dachau, just like thousands of Jewish men who are deported to concentration camps to enforce their emigration.

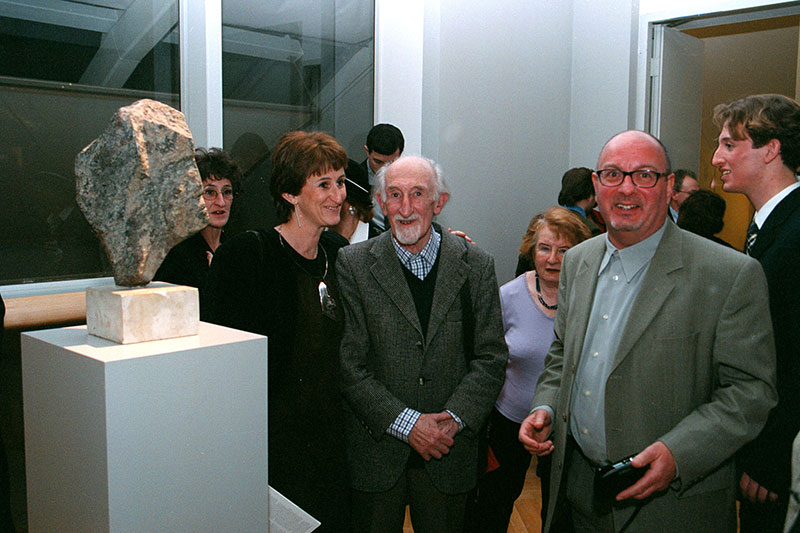

An English visa finally allows Eisenmayer to emigrate to England after all - where he spends the war in five different internment camps. Eisenmayer eventually studied art and became a painter and sculptor. After years In England, Italy and Amsterdam, he finally returned temporarily to Vienna, where he died in 2018, aged 97.

Bus tickets of Ernst Eisenmayer from 1938, Landeck-Galtür

From: Did you see my Alps. A Jewish Love Story. Edited by Hanno Loewy and Gerhard Milchram. Hohenems 2009.

Ernst Eisenmayer, Alpine view

From: Did you see my Alps. A Jewish Love Story. Edited by Hanno Loewy and Gerhard Milchram. Hohenems 2009.

Ernst Eisenmayer (center) with one of his sculptures in his exhibition at the Jewish Museum Vienna, 2002

Ernst Eisenmayer (center) with one of his sculptures in his exhibition at the Jewish Museum Vienna, 2002

Photo: David Peters, Jewish Museum Vienna

47 Ernst Eisenmayer

Ernst Eisenmayer almost made it, but Swiss police sends him back

Drusentor, September 1938

“Two of my Jewish schoolmates had managed to get into Switzerland in time, before the Swiss virtually closed the border for us. But we were getting desperate. Some of our Nazi schoolmates had warned us, if any warning was needed, that things were likely to get worse for us. And we tried to find a way to leave. We went from embassy to embassy of all corners of the world. The answer was always: NO. No money, no ‘proper’ papers, what did we expect? (…)

I had kept in touch with the two friends, who had managed to get to Zurich. They suggested I should try to climb over a rather difficult mountain on the border, the Rhaetikon range and to get into Switzerland that way. It seemed a fair idea. We had nothing to lose, or so we thought, the two of us trying to get away from ‘them’.”[1]

Together with a relative of the same age, a distant cousin named Hans Reisz, seventeen-year-old Ernst Eisenmayer planned his escape in Vienna in the late summer of 1938. They would pose as hikers.

Many years later, Ernst Eisenmayer writes down his memories in England. Some of the details are enigmatic. Memories are not always a reliable friend. How they reached their destination is unclear.

“We travelled through the night to the Western part of Austria, but left the train well before the border, not to arouse any suspicion. There were lots of police and uniformed characters about amid the flags. You could have called it colourful. Then we took the local bus up one valley and stayed the night at a small inn. The village had streamers across the road, then almost compulsory, of ‘Jews are not welcome here’. We had to take chance.”[2]

Eisenmayer has kept a bus ticket from this trip, but it shows Galtür as the destination. He remembers that they hiked for a whole day, over to another valley, then spent the night outdoors. In the early morning they set off again. His dramatic description turns the escape into an exciting adventure.

“There was just enough light to read the map, to make sure of the lay of the land. My limited mountaineering experience came in handy. My cousin had never been any higher than a thousand meters on a mountain near Vienna. He wasn’t the sporty kind.

We were still below the tree line and I have worked out a route to the border. We had arranged to mee our ‘Swiss’ friends on the south side of the Sulzfluh range. We had arranged all details by post and they were coming very much to life that day. Perilous looking rock faces were beginning to get lit up by the rising sun, gloriously beautiful to look at, taking our breath away thinking about the climb ahead.

‚Do we have to get across there?’ asked my cousin already panting a little, as we were approaching the glacier.

‘Yes, that’s the one. And our two pals will be waiting for us the other side!’

I answered to encourage myself and him without the least thought of turning back. Although I began to realize, that it was going to be far from easy.”[3]

On the other side of the mountain, so Eisenmayer in his recollections, they actually meet the friends. A photo shows the two fugitives taking a rest, the Sulzfluh seen from the south in the background. But Eisenmayer's escape story does not end there. At the train station down in the valley, they are stopped by the police. Instead of being able to board the train to Zurich, they are interrogated - and eventually deported back to the German Reich. And sent back to Vienna. Eisenmayer attempted to escape once again a few weeks later, across the border into France. And after the November pogrom, he finds himself in Dachau, just like thousands of Jewish men who are deported to concentration camps to enforce their emigration.

An English visa finally allows Eisenmayer to emigrate to England after all - where he spends the war in five different internment camps. Eisenmayer eventually studied art and became a painter and sculptor. After years In England, Italy and Amsterdam, he finally returned temporarily to Vienna, where he died in 2018, aged 97.

Bus tickets of Ernst Eisenmayer from 1938, Landeck-Galtür

From: Did you see my Alps. A Jewish Love Story. Edited by Hanno Loewy and Gerhard Milchram. Hohenems 2009.