Ingeborg Neufeld> October 1942

48 Ingeborg Neufeld

In hiding and over the mountains: Meinrad Juen helps Ingeborg Neufeld and her family across the border

Gargellen, October 1942

“In September 1942, we were ordered to report to the train station, transport to the east, we were told. At that time we all knew, whether Christians or Jews, what was happening in Poland. Not in detail, but we knew what it was all about. Young SS men bragged about their experiences behind the front.”[1]

Ingeborg Neufeld, her mother Hildegard and her brother Hans Walter have survived until then in Vienna, with forced labor in “war-important factories”. Now they are looking for a way to escape deportation together with the musician Otto Kollmann, Inge's fiancé.

“My mother had had a childhood friend who was a monarchist, moreover a real count, a Herr von Benedek. ... Our count had had a hot love affair with my mother, but they were not allowed to marry, because she came from a rich Jewish family and he from impoverished nobility. It would have been a good marriage, and I could have been a countess....

Mr. von Benedek proved his love to us in another way. He owned an estate in St. Gallenkirch near Schruns, on the Austrian-Swiss border. There he knew the Juen family, who took in guests during vacation periods. The village had lived from smuggling for ages: coffee, cigarettes, and more recently, people. The Juens knew the secret ways, they had their contacts with the border guards. Count Benedek came to Vienna when my mother called. He planned our escape with the help of the Juens. ...

In the morning it was decided that we would not move in at the appointed hour. Now we were hunted game. We thought we would have the forged papers in two or three days. It turned out to be six weeks.

I had my false papers from the factory, Mama had them from Benedek, the problem was Otto and my brother. Besides, the Juens were not yet ready to take us in, it was still high season in the tourist village, so there were too many observers there. It was a matter of holding out in Vienna for the time being. We decided to make our way separately. As a meeting place we determined a bridge arch at the “Gürtel”, every day one further, every day half an hour later. ... We sometimes just walked past each other, whispering information to each other. My job was to hear four sleeping addresses every day on a street corner in the 7th district from a member of the underground movement, to memorize them and pass them on to Mom and my brother. ... I always tried to stay together with Otto. ... We never knew the names of our hosts. Mostly they were very simple people, communists or social democrats, but also others who wanted to acquire a clean slate, especially after Stalingrad.”

After weeks of waiting in hiding, the forged papers are organized for all of them. In October, they travel to Vorarlberg via Munich, survive several controls, and finally reach the Juen family in St. Gallenkirch via Bregenz and Schruns.

“I wanted to live at any price. The cowbells rang, the church bell called the herd home. We were served long forgotten delicacies, fresh fruit, meat, everything drove me to live.

We were supposed to stay for a week to strengthen ourselves, but on the third night Mr. Juen suddenly came in and said we had to leave immediately, we had been reported. We were to take only the bare necessities, we had no porters, only he and his brother would guide us.

On the way I still threw away a lot, because we were climbing up steep paths and were not allowed to make any noise. It was late October and very cold. I slipped into a hole. Juen threw me a rope and pulled me up, after which I couldn't breathe anymore, so he carried me a bit. Otto had slippery shoes on, Mama had to pull him almost the whole way. For several hours we had to lie motionless in a hollow because soldiers were passing by. I snuggled up to Otto. Although we had slept in the same bed so many times, I was still a virgin. The bourgeois prejudices persisted in all dangers. We trembled with fear, cold, and regret over unlived nights of love. ...

At daybreak we moved on, partly already surrounded by snow. We slid. Further, further, urged Juen. The guards are bribed, you have to sneak past them at a certain time. Mama had given Juen all her remaining jewelry for this escape. Many women saved the jewelry, and the children perished. Many smugglers took gold and money, and then denounced those who were being pursued. A thousand miracles happened during our rescue.

The guards did not show the expected light signal. Perhaps they had been replaced, perhaps someone had turned us in. We stopped at a crevice in the rock that could hardly be seen. The Juens pushed us through, whispered that they could go no further with us, handed over what luggage they had carried for us, and said: ‘Run, run, as fast as you can. Over there is Switzerland.’ And we ran.

They took the last of my mother's jewelry, but they got us across. My brother kept close contact with the Juens after the war, he was often in Austria with them, helped them in the difficult years after 1945. I was there on a trip to Berlin, half the village is inhabited by Juens.”

Difficult years await Ingeborg Neufeld even after her escape to Switzerland.

After two years in a Swiss labor camp she finally experiences the end of the war in Lugano. There she and her fiancé are hired by the American secret service and witness secret negotiations with the German SS General Wolff about an early armistice in Upper Italy.

Her life still held many amorous and musical adventures in store for her, which she recounted with relish in her autobiography The Partisan Villa. But she was already writing it under her later name, Inge Ginsberg.

In 2021, she died in Zurich, not without having shown the world once again how much energy even a 90-year-old can have. In the 1950s, she had already written songs for pop singers with her first husband, Otto Kollmann. Now, between 2014 and 2016, she is competing three times with the heavy metal band Tritone Kings in the Swiss preliminary round for the Eurovision Song Contest. Among others with the song “Totenköpfchen“.

[1] Inge Ginsberg, The Partisan Villa. Memories of Flight, Secret Service and Numerous Hit Songs. Munich 2008, p. 65-69.

Lyrics by Inge Ginsberg, music by Pedro H. da Silva and Lucía Caruso. Copyright 2014.

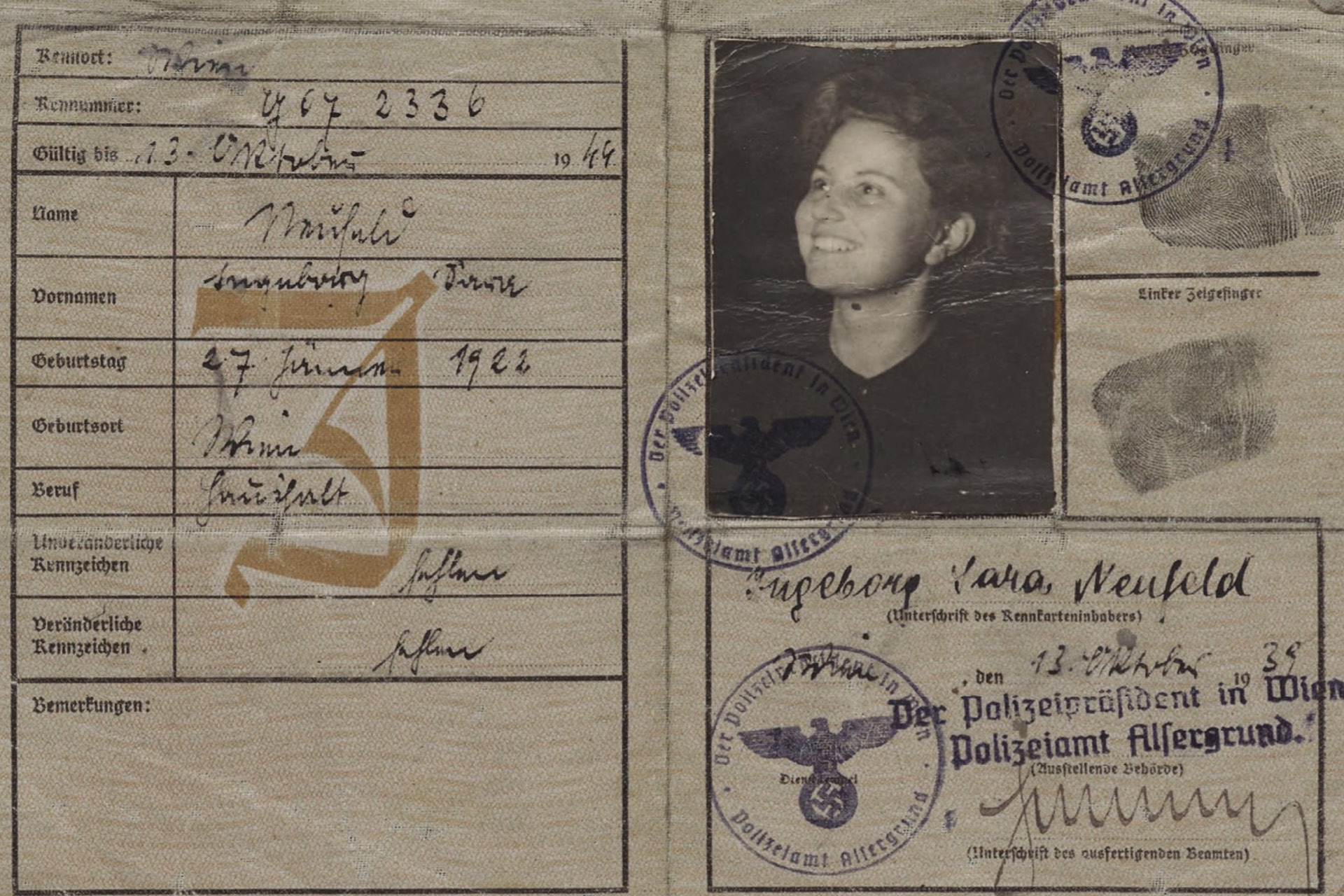

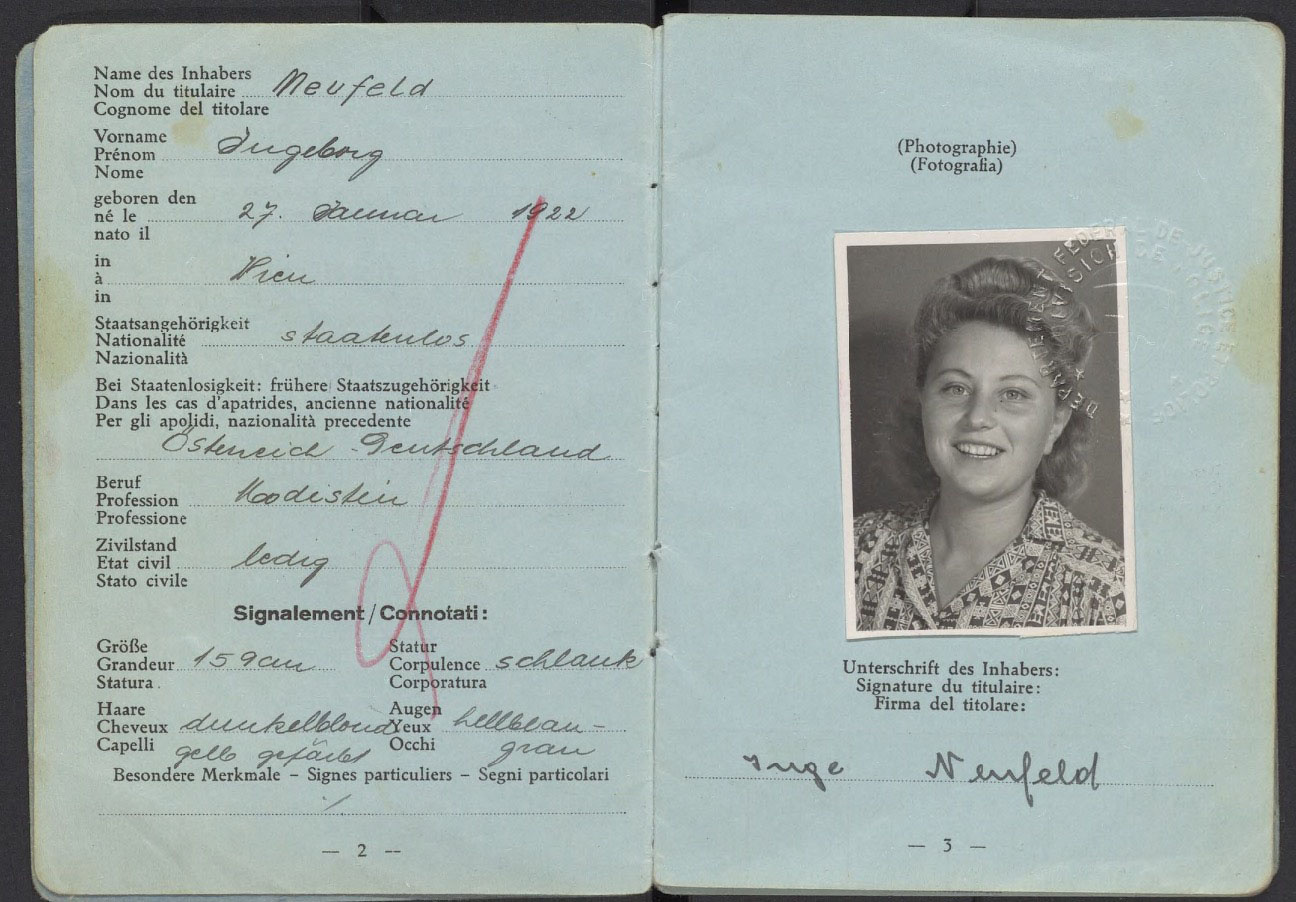

Refugee passport of Inge Neufeld, 1943

Refugee passport of Inge Neufeld, 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Inge Neufeld

Inge Neufeld and Otto Kollmann, 1950

Wikimedia

48 Ingeborg Neufeld

In hiding and over the mountains: Meinrad Juen helps Ingeborg Neufeld and her family across the border

Gargellen, October 1942

“In September 1942, we were ordered to report to the train station, transport to the east, we were told. At that time we all knew, whether Christians or Jews, what was happening in Poland. Not in detail, but we knew what it was all about. Young SS men bragged about their experiences behind the front.”[1]

Ingeborg Neufeld, her mother Hildegard and her brother Hans Walter have survived until then in Vienna, with forced labor in “war-important factories”. Now they are looking for a way to escape deportation together with the musician Otto Kollmann, Inge's fiancé.

“My mother had had a childhood friend who was a monarchist, moreover a real count, a Herr von Benedek. ... Our count had had a hot love affair with my mother, but they were not allowed to marry, because she came from a rich Jewish family and he from impoverished nobility. It would have been a good marriage, and I could have been a countess....

Mr. von Benedek proved his love to us in another way. He owned an estate in St. Gallenkirch near Schruns, on the Austrian-Swiss border. There he knew the Juen family, who took in guests during vacation periods. The village had lived from smuggling for ages: coffee, cigarettes, and more recently, people. The Juens knew the secret ways, they had their contacts with the border guards. Count Benedek came to Vienna when my mother called. He planned our escape with the help of the Juens. ...

In the morning it was decided that we would not move in at the appointed hour. Now we were hunted game. We thought we would have the forged papers in two or three days. It turned out to be six weeks.

I had my false papers from the factory, Mama had them from Benedek, the problem was Otto and my brother. Besides, the Juens were not yet ready to take us in, it was still high season in the tourist village, so there were too many observers there. It was a matter of holding out in Vienna for the time being. We decided to make our way separately. As a meeting place we determined a bridge arch at the “Gürtel”, every day one further, every day half an hour later. ... We sometimes just walked past each other, whispering information to each other. My job was to hear four sleeping addresses every day on a street corner in the 7th district from a member of the underground movement, to memorize them and pass them on to Mom and my brother. ... I always tried to stay together with Otto. ... We never knew the names of our hosts. Mostly they were very simple people, communists or social democrats, but also others who wanted to acquire a clean slate, especially after Stalingrad.”

After weeks of waiting in hiding, the forged papers are organized for all of them. In October, they travel to Vorarlberg via Munich, survive several controls, and finally reach the Juen family in St. Gallenkirch via Bregenz and Schruns.

“I wanted to live at any price. The cowbells rang, the church bell called the herd home. We were served long forgotten delicacies, fresh fruit, meat, everything drove me to live.

We were supposed to stay for a week to strengthen ourselves, but on the third night Mr. Juen suddenly came in and said we had to leave immediately, we had been reported. We were to take only the bare necessities, we had no porters, only he and his brother would guide us.

On the way I still threw away a lot, because we were climbing up steep paths and were not allowed to make any noise. It was late October and very cold. I slipped into a hole. Juen threw me a rope and pulled me up, after which I couldn't breathe anymore, so he carried me a bit. Otto had slippery shoes on, Mama had to pull him almost the whole way. For several hours we had to lie motionless in a hollow because soldiers were passing by. I snuggled up to Otto. Although we had slept in the same bed so many times, I was still a virgin. The bourgeois prejudices persisted in all dangers. We trembled with fear, cold, and regret over unlived nights of love. ...

At daybreak we moved on, partly already surrounded by snow. We slid. Further, further, urged Juen. The guards are bribed, you have to sneak past them at a certain time. Mama had given Juen all her remaining jewelry for this escape. Many women saved the jewelry, and the children perished. Many smugglers took gold and money, and then denounced those who were being pursued. A thousand miracles happened during our rescue.

The guards did not show the expected light signal. Perhaps they had been replaced, perhaps someone had turned us in. We stopped at a crevice in the rock that could hardly be seen. The Juens pushed us through, whispered that they could go no further with us, handed over what luggage they had carried for us, and said: ‘Run, run, as fast as you can. Over there is Switzerland.’ And we ran.

They took the last of my mother's jewelry, but they got us across. My brother kept close contact with the Juens after the war, he was often in Austria with them, helped them in the difficult years after 1945. I was there on a trip to Berlin, half the village is inhabited by Juens.”

Difficult years await Ingeborg Neufeld even after her escape to Switzerland.

After two years in a Swiss labor camp she finally experiences the end of the war in Lugano. There she and her fiancé are hired by the American secret service and witness secret negotiations with the German SS General Wolff about an early armistice in Upper Italy.

Her life still held many amorous and musical adventures in store for her, which she recounted with relish in her autobiography The Partisan Villa. But she was already writing it under her later name, Inge Ginsberg.

In 2021, she died in Zurich, not without having shown the world once again how much energy even a 90-year-old can have. In the 1950s, she had already written songs for pop singers with her first husband, Otto Kollmann. Now, between 2014 and 2016, she is competing three times with the heavy metal band Tritone Kings in the Swiss preliminary round for the Eurovision Song Contest. Among others with the song “Totenköpfchen“.

[1] Inge Ginsberg, The Partisan Villa. Memories of Flight, Secret Service and Numerous Hit Songs. Munich 2008, p. 65-69.