Jura Soyfer and Hugo Ebner> March 13, 1938

51 Jura Soyfer and Hugo Ebner

A sardine can and the wrong newspaper. Jura Soyfer and Hugo Ebner end up in the concentration camp instead of crossing the Schlappiner Joch mountain pass

Gargellen, March 13, 1938

“Jura was released with the February amnesty, and, as I originally believed, did not have a passport. Correct was, he had a passport, but the passport had expired.”[1]

The lawyer Hugo Ebner tells of his joint escape attempt with the writer Jura Soyfer on March 13, 1938.

“When we met on the 11th or 12th to discuss the situation and we found it would be good to leave, the problem was that he didn't have a valid passport. We came to the conclusion we'll try over the mountains. We were reasonably good skiers. I had been skiing the year before in Montafon, in Gargellen, and I knew the area a bit. Besides, it seemed quite convenient to me, when we were asked what we were doing there, to be able to point out that I was already there last year, where politically nothing was going on yet.”[2]

Ebner and Soyfer are Communists, and both are Jews. Soyfer, himself the son of a Jewish refugee family from Russia, had already been imprisoned in Austrofascist Austria in 1937 as an author of anti-fascist satires and cabaret scenes. In February 1938, under German pressure, an amnesty was granted to political prisoners in Austria, actually referring to illegal National Socialists. But paradoxically, some communists were also released, including Jura Soyfer. In the days following the “Anschluss” to Nazi Germany, escape is the order of the day. Unhindered, the two manage to get to Schruns by train with their ski equipment. On foot they walk up to Gargellen. But on the way further to the Schlappiner Joch mountain pass, their plan fails.

“Behind Gargellen we were checked by a gendarmerie patrol consisting of one gendarme, who was not very comfortable with the whole thing, a second one, whom I don't remember, and a third one, who was obviously a Nazi and who insisted on our arrest, ... As a pretext he used the following: There was in my knapsack a can of sardines wrapped, probably unnecessarily, in a piece of newspaper. This newspaper was a quite legal trade union newspaper from 1936, i.e. a patriotic one. But he used that as a pretext, considered it an illegal newspaper, and insisted that we be arrested and come along. He was obviously the youngest one who set the tone.”[3]

The prisoners spend one night in St. Gallenkirch, then they are imprisoned in Bludenz and interrogated by the Gestapo. Still in spring, they are transferred to Innsbruck, where they meet, among others, the former governor of Vorarlberg and short-term federal chancellor Otto Ender in the prison yard, and finally to the Dachau concentration camp in June 1938. There Jura Soyfer writes the “Dachau Song,” which has become legendary. From Dachau they are deported to Buchenwald concentration camp in September. While working in the corpsmen's detachment, Soyfer is infected with typhus. He died in Buchenwald on the night of February 15-16, 1939, already in possession of emigration papers to the USA. Hugo Ebner, on the other hand, is tortured in Buchenwald. He will suffer the after-effects of the notorious “tree hanging” for the rest of his life. In May 1939 he is released and returns to Vienna.

Hugo Ebner's girlfriend Rosl Kraus also remembers March 1938. These days also haunt her for the rest of her life.

“And then the memory that I unfortunately cannot forget: The Chancellor's radio address, farewell to Austria as an independent state, and then the night on our usual mattress camp on the floor of my sublet room, the terrible fear for Hugo, (.... ) and his decision that he wants to go with Jura over the mountains to Switzerland and I should come along, all with skis and I cried all night and so did many thousands that night and then suddenly early in the morning when we were saying goodbye – I was supposed to follow them both, to meet them in Vorarlberg – he said something that made me so indignant, I don't remember exactly what, but something like, ‘if a girl is with them, they are more protected, it's more like a ski trip’ and my suddenly unfortunate rage: not for my protection I should come along, but as a shield, so to speak, take the risk of being caught on me and our short argument still in the apartment door and off he was.... That still bores and gnaws in me today, perhaps I could have spared them everything that then came their way, if I had not been so terribly selfish.”[4]

But Rosl Kraus had every reason to argue with Ebner. As a Jew, she was just as much at risk. After the arrest of her friends, she realized that she too would have to flee. Her brother, living in Paris, managed to find a French acquaintance who was willing to enter into a marriage of convenience with her in order to obtain French citizenship for her. As Rosl Jurkiewicz, she was able to emigrate to Paris in 1939, and that same spring, with the help of a cousin, on to London. There she met Hugo Ebner again. He had also managed to flee to London in the summer of 1939.

In Great Britain, however, a camp for “those willing to leave the country” was waiting for him, and after the beginning of the war, internment as an “enemy alien” in a labor camp in Canada.

Once again they had to wait two years before they were allowed to start a life together. After the war, they returned to Vienna and finally were able to marry. Rosl Ebner became a physician and Hugo Ebner a lawyer – not least known for his commitment to the pensions of Jewish survivors of persecution and displaced persons.

[1] Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider, Austrian Pensions for Jewish Displaced Persons. The Ebner Law Firm: Actors-Networks-Files. Vienna 2017, p. 241.

[4] Ibid., p. 33.

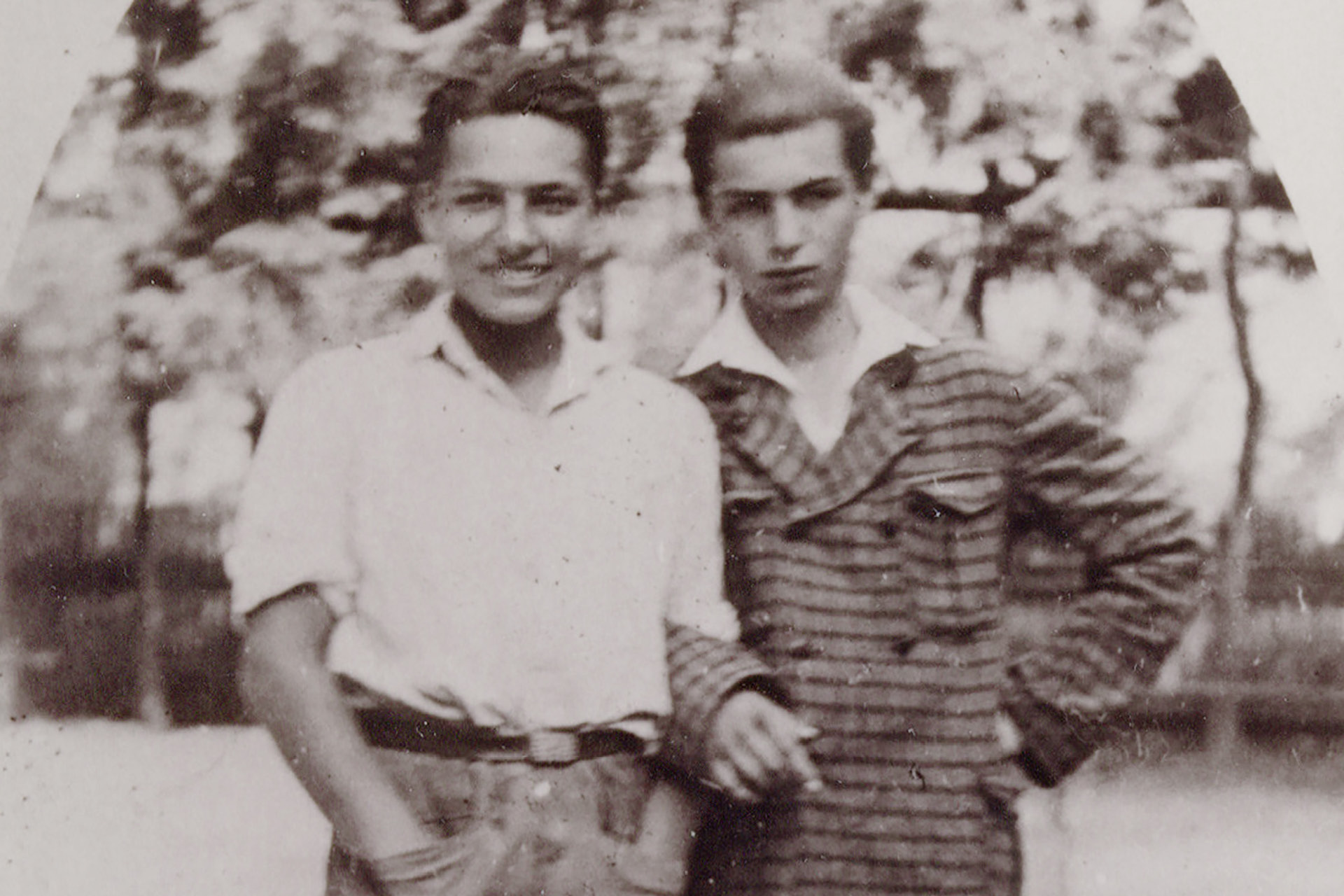

Jura Soyfer (seated right) with socialist youths on a skiing trip on the Ötscher, January 1930

Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, Vienna

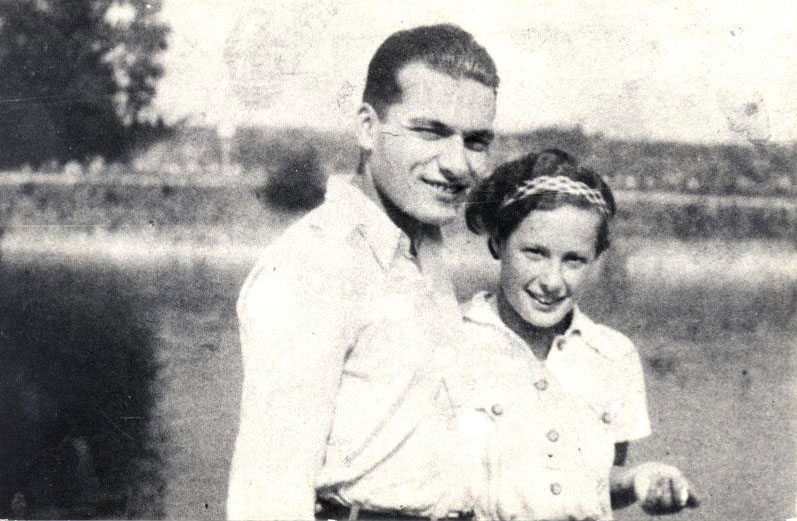

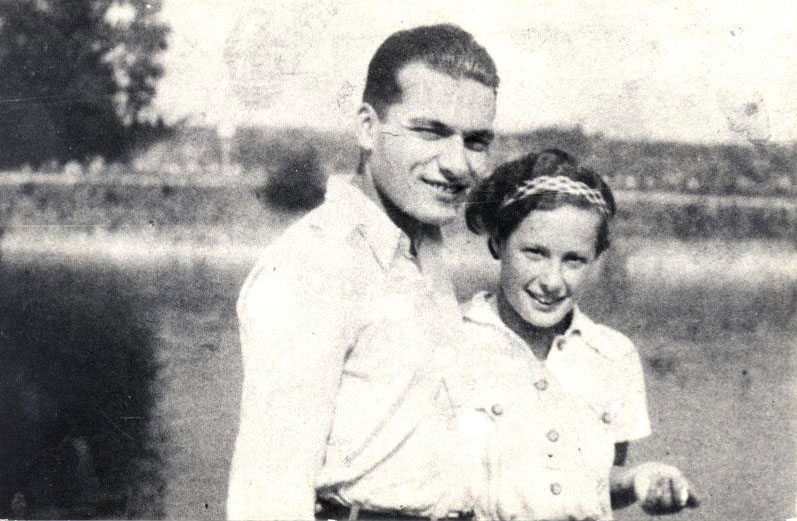

Jura Soyfer and Maria Szecsi, about 1937

Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, Vienna

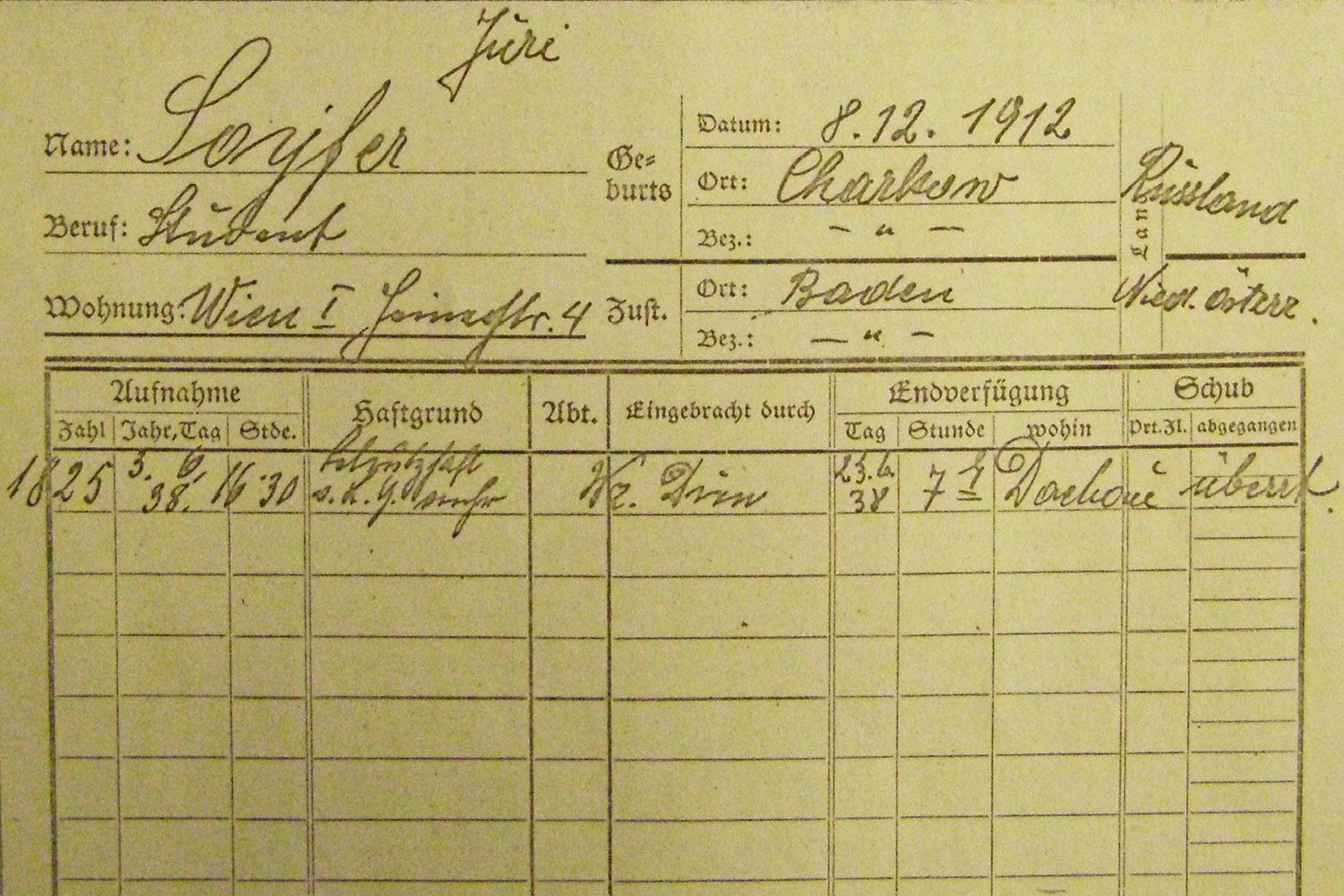

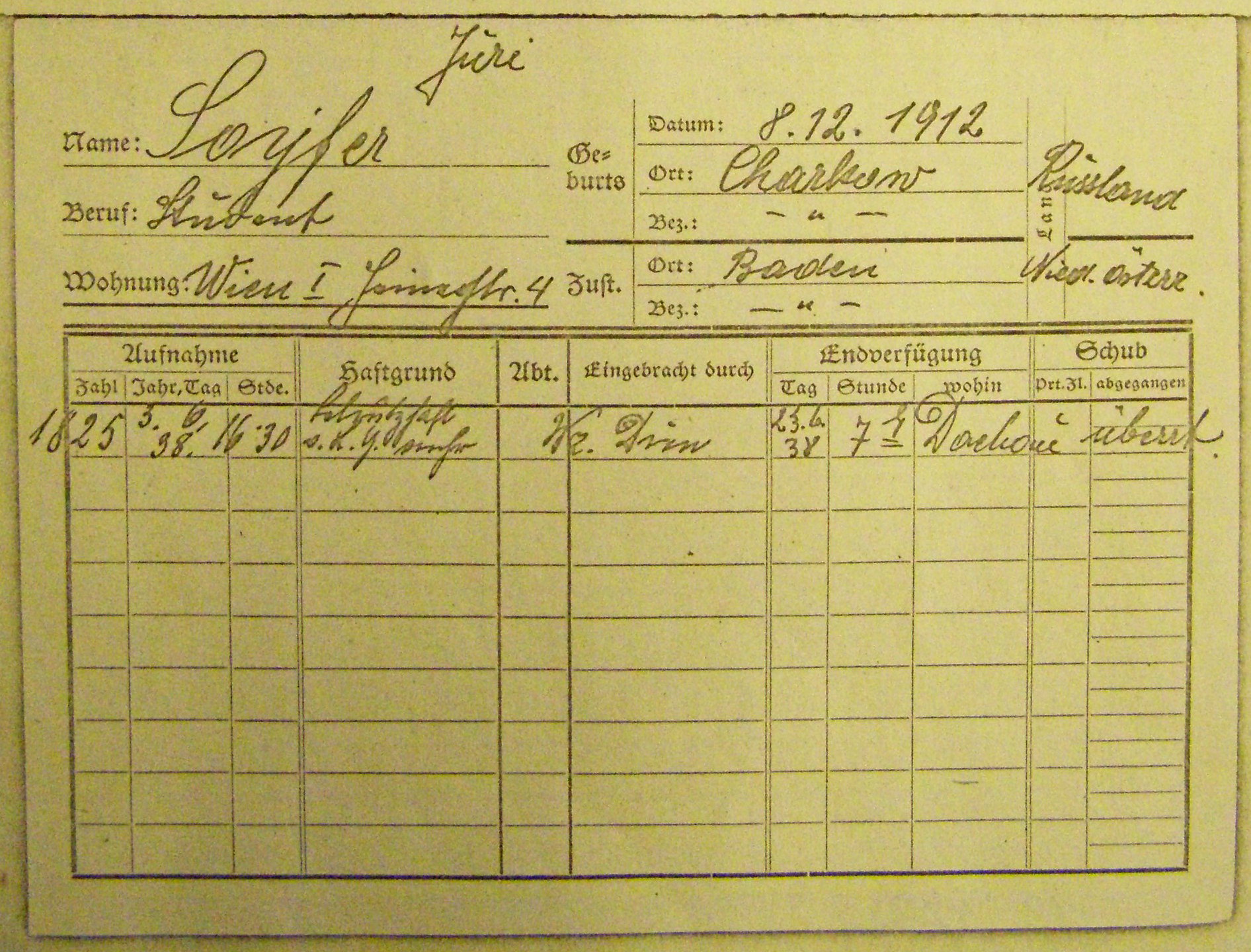

Jura Soyfer's prisoner card and transfer to Dachau concentration camp

Files of the Vienna Police Headquarters, Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, Vienna

51 Jura Soyfer and Hugo Ebner

A sardine can and the wrong newspaper. Jura Soyfer and Hugo Ebner end up in the concentration camp instead of crossing the Schlappiner Joch mountain pass

Gargellen, March 13, 1938

“Jura was released with the February amnesty, and, as I originally believed, did not have a passport. Correct was, he had a passport, but the passport had expired.”[1]

The lawyer Hugo Ebner tells of his joint escape attempt with the writer Jura Soyfer on March 13, 1938.

“When we met on the 11th or 12th to discuss the situation and we found it would be good to leave, the problem was that he didn't have a valid passport. We came to the conclusion we'll try over the mountains. We were reasonably good skiers. I had been skiing the year before in Montafon, in Gargellen, and I knew the area a bit. Besides, it seemed quite convenient to me, when we were asked what we were doing there, to be able to point out that I was already there last year, where politically nothing was going on yet.”[2]

Ebner and Soyfer are Communists, and both are Jews. Soyfer, himself the son of a Jewish refugee family from Russia, had already been imprisoned in Austrofascist Austria in 1937 as an author of anti-fascist satires and cabaret scenes. In February 1938, under German pressure, an amnesty was granted to political prisoners in Austria, actually referring to illegal National Socialists. But paradoxically, some communists were also released, including Jura Soyfer. In the days following the “Anschluss” to Nazi Germany, escape is the order of the day. Unhindered, the two manage to get to Schruns by train with their ski equipment. On foot they walk up to Gargellen. But on the way further to the Schlappiner Joch mountain pass, their plan fails.

“Behind Gargellen we were checked by a gendarmerie patrol consisting of one gendarme, who was not very comfortable with the whole thing, a second one, whom I don't remember, and a third one, who was obviously a Nazi and who insisted on our arrest, ... As a pretext he used the following: There was in my knapsack a can of sardines wrapped, probably unnecessarily, in a piece of newspaper. This newspaper was a quite legal trade union newspaper from 1936, i.e. a patriotic one. But he used that as a pretext, considered it an illegal newspaper, and insisted that we be arrested and come along. He was obviously the youngest one who set the tone.”[3]

The prisoners spend one night in St. Gallenkirch, then they are imprisoned in Bludenz and interrogated by the Gestapo. Still in spring, they are transferred to Innsbruck, where they meet, among others, the former governor of Vorarlberg and short-term federal chancellor Otto Ender in the prison yard, and finally to the Dachau concentration camp in June 1938. There Jura Soyfer writes the “Dachau Song,” which has become legendary. From Dachau they are deported to Buchenwald concentration camp in September. While working in the corpsmen's detachment, Soyfer is infected with typhus. He died in Buchenwald on the night of February 15-16, 1939, already in possession of emigration papers to the USA. Hugo Ebner, on the other hand, is tortured in Buchenwald. He will suffer the after-effects of the notorious “tree hanging” for the rest of his life. In May 1939 he is released and returns to Vienna.

Hugo Ebner's girlfriend Rosl Kraus also remembers March 1938. These days also haunt her for the rest of her life.

“And then the memory that I unfortunately cannot forget: The Chancellor's radio address, farewell to Austria as an independent state, and then the night on our usual mattress camp on the floor of my sublet room, the terrible fear for Hugo, (.... ) and his decision that he wants to go with Jura over the mountains to Switzerland and I should come along, all with skis and I cried all night and so did many thousands that night and then suddenly early in the morning when we were saying goodbye – I was supposed to follow them both, to meet them in Vorarlberg – he said something that made me so indignant, I don't remember exactly what, but something like, ‘if a girl is with them, they are more protected, it's more like a ski trip’ and my suddenly unfortunate rage: not for my protection I should come along, but as a shield, so to speak, take the risk of being caught on me and our short argument still in the apartment door and off he was.... That still bores and gnaws in me today, perhaps I could have spared them everything that then came their way, if I had not been so terribly selfish.”[4]

But Rosl Kraus had every reason to argue with Ebner. As a Jew, she was just as much at risk. After the arrest of her friends, she realized that she too would have to flee. Her brother, living in Paris, managed to find a French acquaintance who was willing to enter into a marriage of convenience with her in order to obtain French citizenship for her. As Rosl Jurkiewicz, she was able to emigrate to Paris in 1939, and that same spring, with the help of a cousin, on to London. There she met Hugo Ebner again. He had also managed to flee to London in the summer of 1939.

In Great Britain, however, a camp for “those willing to leave the country” was waiting for him, and after the beginning of the war, internment as an “enemy alien” in a labor camp in Canada.

Once again they had to wait two years before they were allowed to start a life together. After the war, they returned to Vienna and finally were able to marry. Rosl Ebner became a physician and Hugo Ebner a lawyer – not least known for his commitment to the pensions of Jewish survivors of persecution and displaced persons.

[1] Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider, Austrian Pensions for Jewish Displaced Persons. The Ebner Law Firm: Actors-Networks-Files. Vienna 2017, p. 241.

[4] Ibid., p. 33.

Jura Soyfer (seated right) with socialist youths on a skiing trip on the Ötscher, January 1930

Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, Vienna

Jura Soyfer and Maria Szecsi, about 1937

Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance, Vienna