Greek forced laborers > 1942 - 1943

52 Greek forced laborers

“Today Ulysses was with me”. Greek forced laborers flee over the passes into the Prättigau

Partenen – Gortipohl – Schruns – Latschau, 1942-1943

Thousands of prisoners of war are working as forced laborers in Vorarlberg as in the entire German Reich, starting in 1939. “Civilian workers” are brought into the country too, not all of them come voluntarily. In total, more than 20,000 people, Ukrainians and French, Russians and Poles, Italians, Belgians, Bulgarians and Greeks, work in Vorarlberg under diverse conditions. They work in the agricultural sector, in industry and, last but not least, on the large construction sites of the power plants that are being built in the Montafon valley. Large investments were made to secure the growing power consumption of the armaments industry in the German Reich.

Some of them let themselves be recruited as “civilian workers”. Their status allows them modest earnings and a certain freedom of movement, which however often turns out to be an illusion. Others are used as prisoners of war for forced labor in violation of international law. Concentration camp prisoners are also forced to work. The treatment of so-called “Ostarbeiter” from Russia or the Ukraine, who are classified as “racially inferior” and kept in strict camp confinement, is particularly bad. Brutal punishments, isolation from one another, miserable working conditions and accidents on the dangerous construction sites in the high mountains are the norm at many sites. For the most part, those who are housed alone or in small groups scattered around the province in direct contact with their employers like farmers fare somewhat better. A few people try to help the prisoners of war, like the nurse Pauline Wittwer from Gaschurn, who gives clothes and food to French prisoners of war. She is denounced, finally arrested and sentenced. After seven different prisons, she is deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp and is only released after a year, seriously ill.

Time and again, forced laborers also attempted to escape. Most of them fail and end in severe imprisonment or death. However, 48 Greeks, organized in various groups, actually succeeded in escaping in 1942 and 1943.

In August 1942, a first group of Greek forced laborers manages to escape over the Grubenpass to St. Antönien in the Swiss Prättigau valley. A Swiss physician is called to examine them – and apparently also to help the police to question the “exotic” guests. His account can be found in the dossier of the Swiss aliens police.

“Today Odysseus was with me, Odysseus, who lay ten years before Troy, who on his return home was lost in the storm and has now wandered for ten years.... Today the policeman comes along with three men, all without headgear, with somewhat tattered shoes, in long striped pants, one dressed only with a shirt, the second also with a worn vest; the third has a smock, undoubtedly somewhat older, certainly of Central European cut. The three, says the policeman, are Greeks and crossed our border today. I should examine them and possibly take their personal data. Difficult thing: they don't respond to German, French, Italian or English. ... But after all, thirty-five years ago I learned Greek. So let's give it a try!”

Stammering, with the help of memories of his Homer reading in school and quoting turns of phrase from the Odyssey, the physician actually manages to record the particulars of the first fugitive. Odysseas Konstantinidis, a former tobacco worker from Xanthi in Thrace. Like his comrades, he had been employed in Latschau by the Hinteregger company to build roads.

Other forced laborers from the Montafon region are to follow. A year later, a Greek group of eight foreign workers manages to escape. Their leader, Jakob Tsitrian, was last employed in Gaschurn as a construction worker for the Jäger company. They report to the Swiss authorities about false promises and bad treatment, lack of food and beatings. Above all, the Greeks deployed in Vorarlberg are afraid of being drafted into the Bulgarian army. Parts of Greece are occupied by Bulgaria and on September 25, 1943, Greeks fit for military service are to be forcibly recruited from this region, even if they are in the German Reich.

Even from Hohenems two Greeks, employed in the Klien brickyard, are making their escape for this reason in September 1943. They, too, take the long way over the mountains and go over the Plasseggen Pass into Prättigau.

In the night of September 12, another group of eight Greek foreign workers, who had worked in Latschau and also in Hohenems, follow them over the Tilisuna-Furka. And the very next day nine Greek prisoners of war under the leadership of Leonidas Pasajanidis reach Switzerland via the Schesaplana. Their military papers had been taken away from them and they had been falsely declared as civilian workers in order to use them for forced labor on a tunnel construction in the Montafon. They, too, feared that they would be sent to the Bulgarian army.

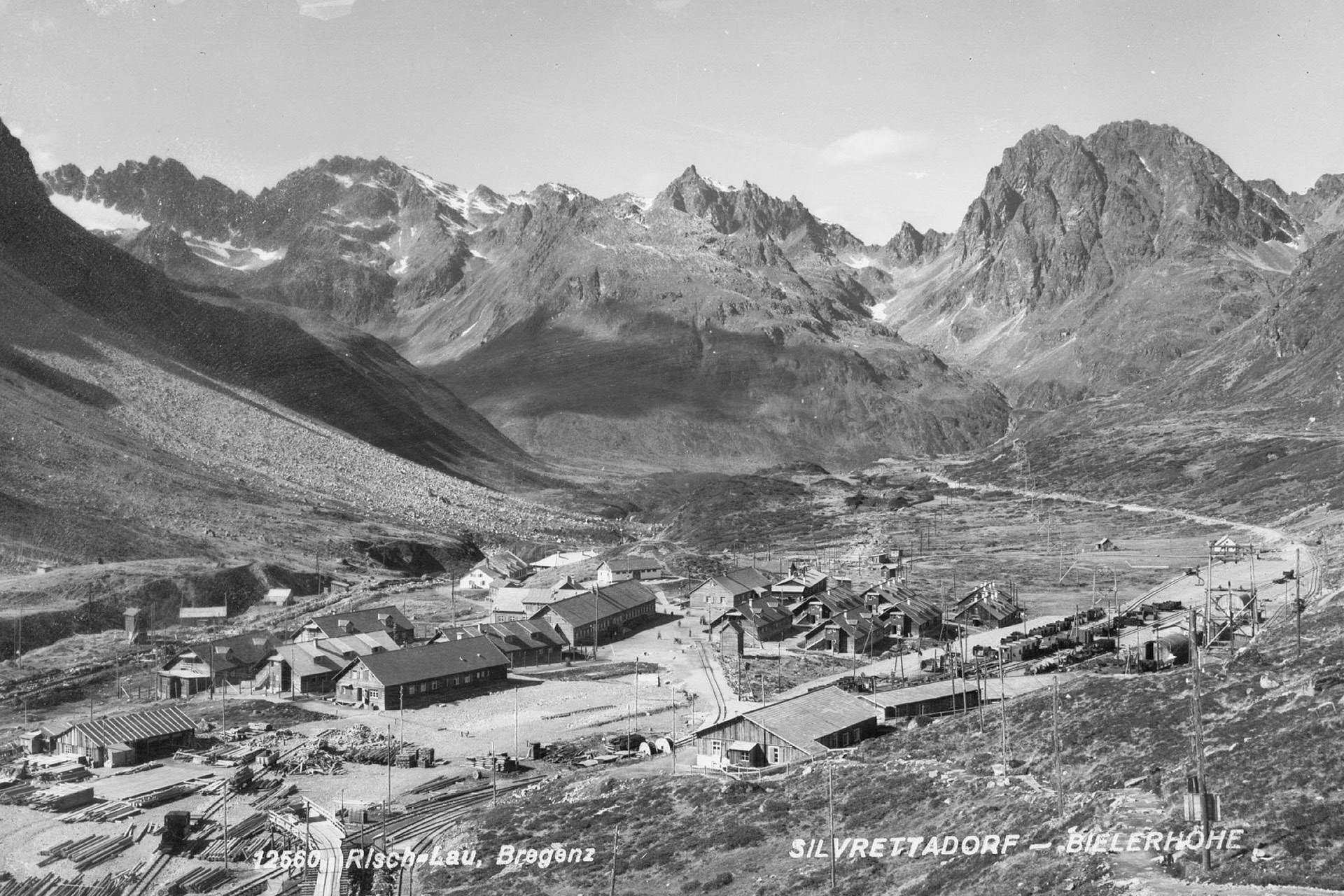

Finally, on September 17, the largest group from the Seespitz camp, up in the Silvretta mountains, set out over the Klosterpass. They are led by Anastasios Georgollas, who had heard about the successful escape attempts of the last days. They are fourteen men, from various work camps at the Seespitz, in the Silvretta village or even in Gortipohl.

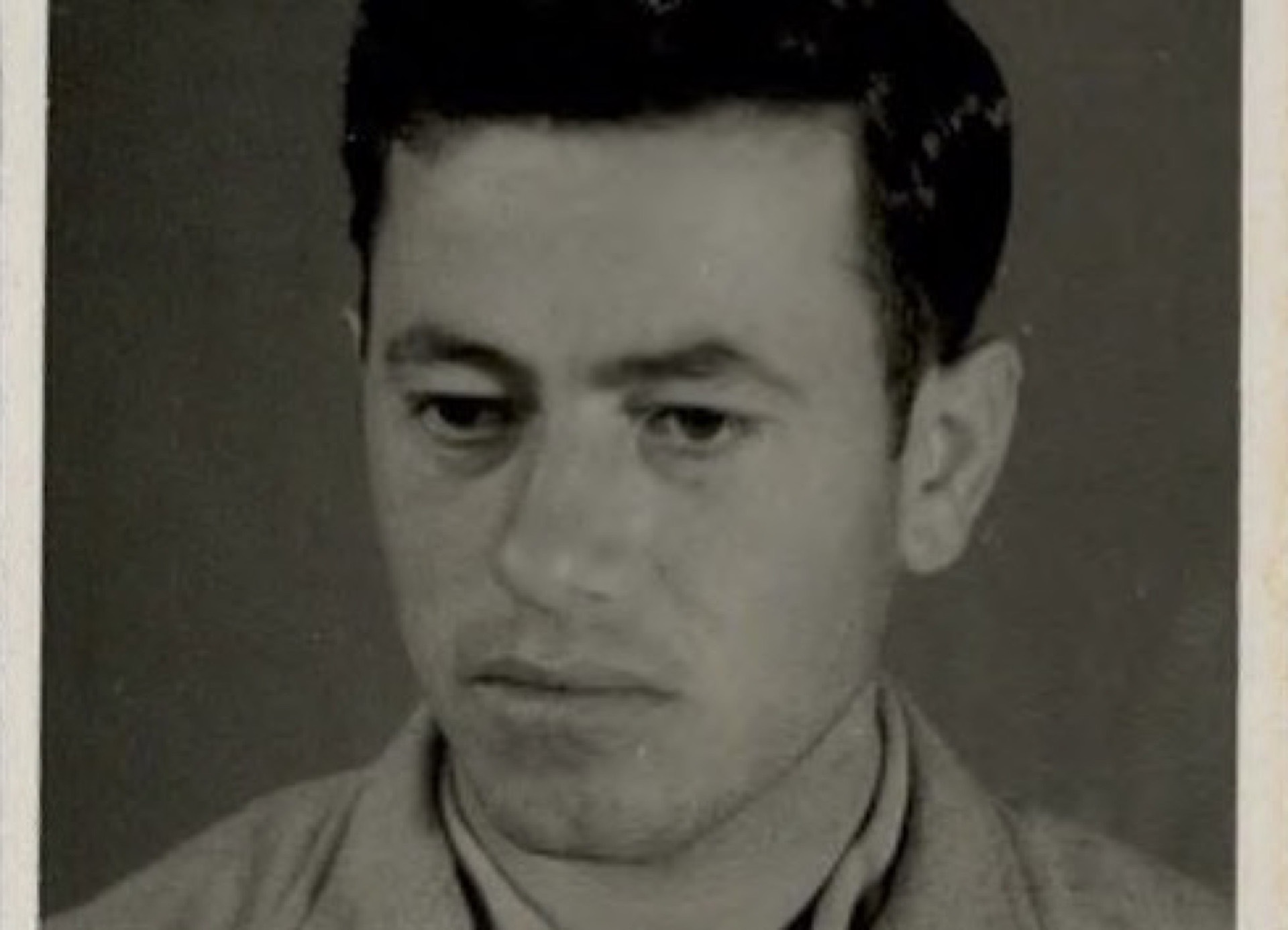

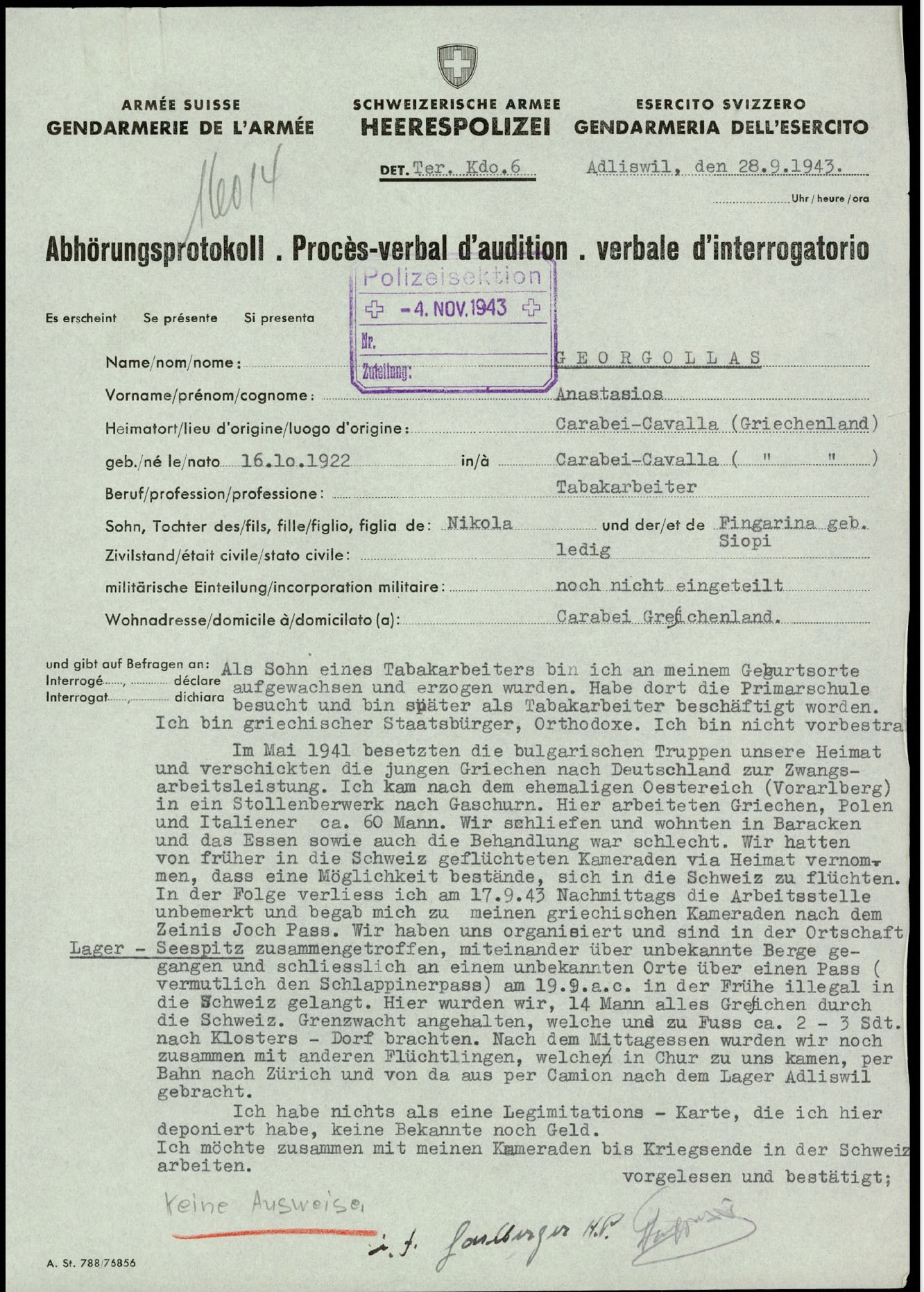

In the early morning hours of September 19, they reach Switzerland. Georgollas and his comrades are taken to the Adliswil internment camp near Zurich, where they are handed over to the Swiss army police. Georgollas also comes from the vicinity of Xanthi in Thrace. He too was employed as a tobacco worker before the war began in 1941 with the occupation of his homeland by Bulgarian troops – and he was sent to the German Reich as a forced laborer. On September 28, Georgollas is interrogated by the army police.

“I came to the former Austria (Vorarlberg) to a mining tunnel in Gaschurn. Greeks, Poles and Italians worked here, about 60 men. We slept and lived in barracks and the food as well as the treatment was bad. We had heard from comrades who had fled to Switzerland in the past that there was a possibility of escaping to Switzerland. (...) We organized ourselves and met in the village of Seespitz, walked together over unknown mountains and finally reached Switzerland illegally at an unknown place over a pass (...) in the early morning. Here we, 14 men all Greeks were stopped by the Swiss border guards, who took us on foot for about 2-3 hours to Klosters-Dorf. After lunch, together with other refugees who had joined us in Chur, we were taken by train to Zurich and from there by truck to the Adliswil camp. I have nothing but a legitimation card which I deposited here, no acquaintances nor money. I want to work in Switzerland together with my comrades until the end of the war.”[4]

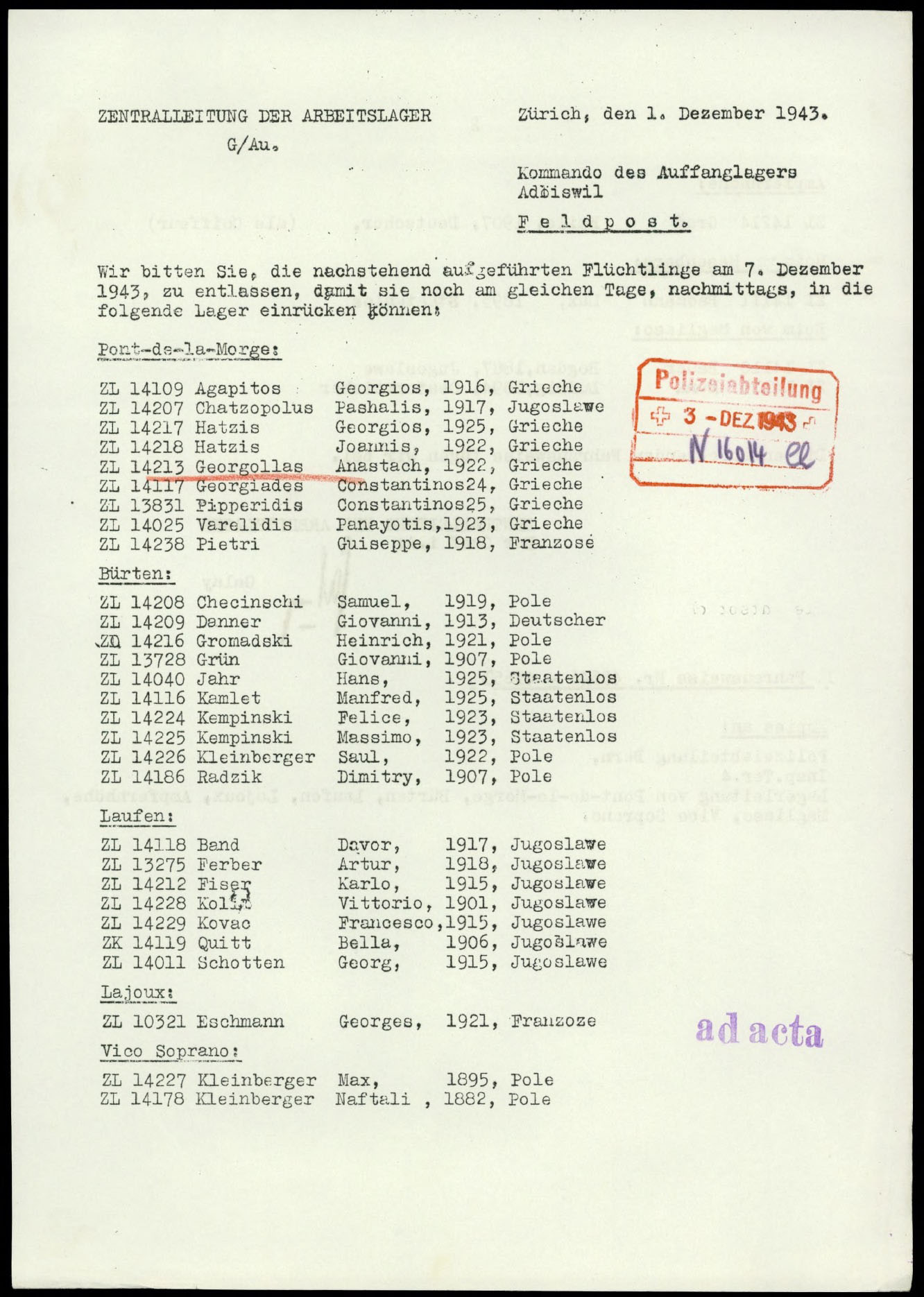

And indeed, on December 8, Georgollas and some of his comrades enter the Pont-de-la-Morge labor camp in the canton of Valais. Like him, the rest of the Greeks spend the rest of the war in Switzerland.

Recommended Reading:

Michael Kasper, „‘Durchgang ist hier strengstens verboten!‘ Die Grenze zwischen Montafon und Prättigau in der NS-Zeit 1938-1945“, in: Edith Hessenberger (Ed.), Grenzüberschreitungen. Von Schleppern, Schmugglern, Flüchtlingen. Schruns 2008, pp. 79-108.

Links:

In the Montafon valley, 15 memorial plaques commemorate victims and resistance under National Socialism. The locations can be found on:

www.stand-montafon.at/erinnerungsorte

[1] 15 Places - 15 Stories. Texts locate memories of National Socialism in the Montafon. Ed. By Stand Montafon, Schruns 2021, p. 35

[2] For the following see the dissertation of Jens Gassmann, Zwangsarbeit in Vorarlberg während der NS-Zeit unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Situation auf den Illwerke-Baustellen. Vienna 2005.

[3] Report in a local Prättigau newspaper in 1942, preserved undated in a Swiss police dossier documenting the escape of Odysseas Konstantinides, who together with two comrades crossed the border on August 29, 1942 at the Grubenpass.

[4] Dossier Anastasios Georgollas, Swiss Federal Archive, Bern.

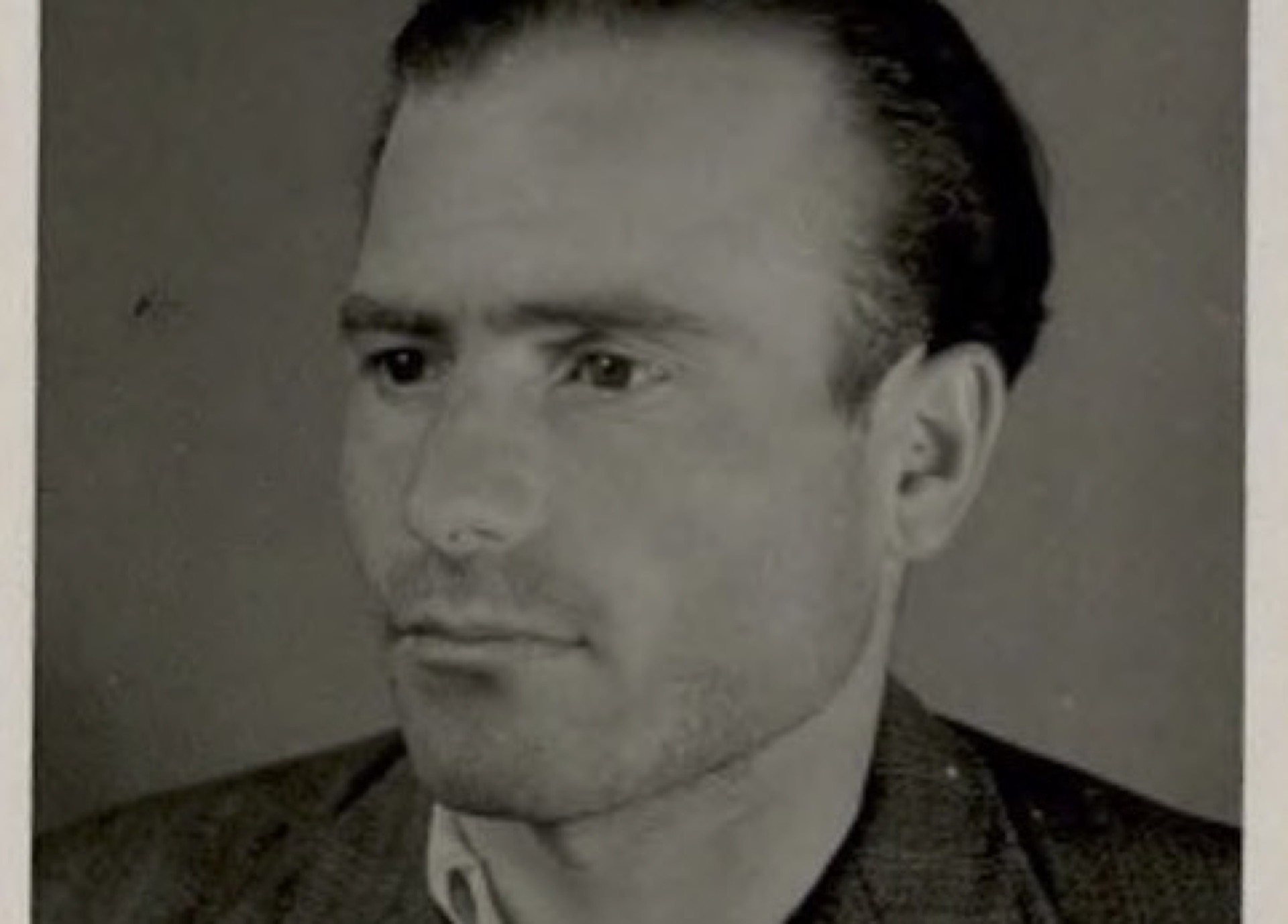

Interception report Anastasios Georgollas, Adliswil camp, 28 September 1943

Interception report Anastasios Georgollas, Adliswil camp, 28 September 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Anastasios Georgollas

List of refugees to be transferred from the Adliswil camp to other camps, December 1, 1943

List of refugees to be transferred from the Adliswil camp to other camps, December 1, 1943

Swiss Federal Archive, Dossier Anastasios Georgollas

52 Greek forced laborers

“Today Ulysses was with me”. Greek forced laborers flee over the passes into the Prättigau

Partenen – Gortipohl – Schruns – Latschau, 1942-1943

Thousands of prisoners of war are working as forced laborers in Vorarlberg as in the entire German Reich, starting in 1939. “Civilian workers” are brought into the country too, not all of them come voluntarily. In total, more than 20,000 people, Ukrainians and French, Russians and Poles, Italians, Belgians, Bulgarians and Greeks, work in Vorarlberg under diverse conditions. They work in the agricultural sector, in industry and, last but not least, on the large construction sites of the power plants that are being built in the Montafon valley. Large investments were made to secure the growing power consumption of the armaments industry in the German Reich.

Some of them let themselves be recruited as “civilian workers”. Their status allows them modest earnings and a certain freedom of movement, which however often turns out to be an illusion. Others are used as prisoners of war for forced labor in violation of international law. Concentration camp prisoners are also forced to work. The treatment of so-called “Ostarbeiter” from Russia or the Ukraine, who are classified as “racially inferior” and kept in strict camp confinement, is particularly bad. Brutal punishments, isolation from one another, miserable working conditions and accidents on the dangerous construction sites in the high mountains are the norm at many sites. For the most part, those who are housed alone or in small groups scattered around the province in direct contact with their employers like farmers fare somewhat better. A few people try to help the prisoners of war, like the nurse Pauline Wittwer from Gaschurn, who gives clothes and food to French prisoners of war. She is denounced, finally arrested and sentenced. After seven different prisons, she is deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp and is only released after a year, seriously ill.

Time and again, forced laborers also attempted to escape. Most of them fail and end in severe imprisonment or death. However, 48 Greeks, organized in various groups, actually succeeded in escaping in 1942 and 1943.

In August 1942, a first group of Greek forced laborers manages to escape over the Grubenpass to St. Antönien in the Swiss Prättigau valley. A Swiss physician is called to examine them – and apparently also to help the police to question the “exotic” guests. His account can be found in the dossier of the Swiss aliens police.

“Today Odysseus was with me, Odysseus, who lay ten years before Troy, who on his return home was lost in the storm and has now wandered for ten years.... Today the policeman comes along with three men, all without headgear, with somewhat tattered shoes, in long striped pants, one dressed only with a shirt, the second also with a worn vest; the third has a smock, undoubtedly somewhat older, certainly of Central European cut. The three, says the policeman, are Greeks and crossed our border today. I should examine them and possibly take their personal data. Difficult thing: they don't respond to German, French, Italian or English. ... But after all, thirty-five years ago I learned Greek. So let's give it a try!”

Stammering, with the help of memories of his Homer reading in school and quoting turns of phrase from the Odyssey, the physician actually manages to record the particulars of the first fugitive. Odysseas Konstantinidis, a former tobacco worker from Xanthi in Thrace. Like his comrades, he had been employed in Latschau by the Hinteregger company to build roads.

Other forced laborers from the Montafon region are to follow. A year later, a Greek group of eight foreign workers manages to escape. Their leader, Jakob Tsitrian, was last employed in Gaschurn as a construction worker for the Jäger company. They report to the Swiss authorities about false promises and bad treatment, lack of food and beatings. Above all, the Greeks deployed in Vorarlberg are afraid of being drafted into the Bulgarian army. Parts of Greece are occupied by Bulgaria and on September 25, 1943, Greeks fit for military service are to be forcibly recruited from this region, even if they are in the German Reich.

Even from Hohenems two Greeks, employed in the Klien brickyard, are making their escape for this reason in September 1943. They, too, take the long way over the mountains and go over the Plasseggen Pass into Prättigau.

In the night of September 12, another group of eight Greek foreign workers, who had worked in Latschau and also in Hohenems, follow them over the Tilisuna-Furka. And the very next day nine Greek prisoners of war under the leadership of Leonidas Pasajanidis reach Switzerland via the Schesaplana. Their military papers had been taken away from them and they had been falsely declared as civilian workers in order to use them for forced labor on a tunnel construction in the Montafon. They, too, feared that they would be sent to the Bulgarian army.

Finally, on September 17, the largest group from the Seespitz camp, up in the Silvretta mountains, set out over the Klosterpass. They are led by Anastasios Georgollas, who had heard about the successful escape attempts of the last days. They are fourteen men, from various work camps at the Seespitz, in the Silvretta village or even in Gortipohl.

In the early morning hours of September 19, they reach Switzerland. Georgollas and his comrades are taken to the Adliswil internment camp near Zurich, where they are handed over to the Swiss army police. Georgollas also comes from the vicinity of Xanthi in Thrace. He too was employed as a tobacco worker before the war began in 1941 with the occupation of his homeland by Bulgarian troops – and he was sent to the German Reich as a forced laborer. On September 28, Georgollas is interrogated by the army police.

“I came to the former Austria (Vorarlberg) to a mining tunnel in Gaschurn. Greeks, Poles and Italians worked here, about 60 men. We slept and lived in barracks and the food as well as the treatment was bad. We had heard from comrades who had fled to Switzerland in the past that there was a possibility of escaping to Switzerland. (...) We organized ourselves and met in the village of Seespitz, walked together over unknown mountains and finally reached Switzerland illegally at an unknown place over a pass (...) in the early morning. Here we, 14 men all Greeks were stopped by the Swiss border guards, who took us on foot for about 2-3 hours to Klosters-Dorf. After lunch, together with other refugees who had joined us in Chur, we were taken by train to Zurich and from there by truck to the Adliswil camp. I have nothing but a legitimation card which I deposited here, no acquaintances nor money. I want to work in Switzerland together with my comrades until the end of the war.”[4]

And indeed, on December 8, Georgollas and some of his comrades enter the Pont-de-la-Morge labor camp in the canton of Valais. Like him, the rest of the Greeks spend the rest of the war in Switzerland.

Recommended Reading:

Michael Kasper, „‘Durchgang ist hier strengstens verboten!‘ Die Grenze zwischen Montafon und Prättigau in der NS-Zeit 1938-1945“, in: Edith Hessenberger (Ed.), Grenzüberschreitungen. Von Schleppern, Schmugglern, Flüchtlingen. Schruns 2008, pp. 79-108.

Links:

In the Montafon valley, 15 memorial plaques commemorate victims and resistance under National Socialism. The locations can be found on:

www.stand-montafon.at/erinnerungsorte

[1] 15 Places - 15 Stories. Texts locate memories of National Socialism in the Montafon. Ed. By Stand Montafon, Schruns 2021, p. 35

[2] For the following see the dissertation of Jens Gassmann, Zwangsarbeit in Vorarlberg während der NS-Zeit unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Situation auf den Illwerke-Baustellen. Vienna 2005.

[3] Report in a local Prättigau newspaper in 1942, preserved undated in a Swiss police dossier documenting the escape of Odysseas Konstantinides, who together with two comrades crossed the border on August 29, 1942 at the Grubenpass.

[4] Dossier Anastasios Georgollas, Swiss Federal Archive, Bern.