Border Police> 1938 - 1945

6 Border Police Commissariat

Interrogated by the Gestapo: Existences are decided at the Border Police Commissioners' Office

Bregenz, 1938 to 1945

After the so-called “Anschluss” of Austria to Nazi Germany, the Secret State Police, or Gestapo for short, was also organized in Vorarlberg in April 1938. Officially, the branch of the state persecution apparatus was called the “Bregenz Border Police Commissariat” and was subordinate to the state police headquarters in Innsbruck. Its headquarters were established at Römerstraße No. 7. After the conquest of France and the German invasion of Yugoslavia, the border with Switzerland was one of the last “windows into a free country”.1 This had an effect not least on the activities of the police, who from the autumn of 1938 tried to prevent border crossings into Switzerland by all means. For both across the Rhine and in the mountains, people who had been persecuted in the German Reich for racist and political reasons now tried to reach freedom this way. The main person responsible for surveillance was initially Joseph Schreieder, the first head of the border police command, who had been transferred from Munich first to Lindau and then on to Bregenz at the beginning of 1938.2

Robert Ernst was one of the first to be arrested by this newly formed Gestapo unit. Born in 1916, he had just completed his military service in the Bregenz barracks and, as a soldier in the previous Austrian army, refused to take the oath to the new “Führer”. His father Oskar Ernst, who came from Moravia, had opened several fashion shops in Vorarlberg from 1905 and soon moved to the provincial capital. As a soldier, he had soon returned wounded from the First World War - and became involved in the care of war-disabled people in the city hospital, for which he was honored by the Red Cross in 1916. Just three years later he died as a result of his war injury and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Hohenems.

After Robert's arrest by the Gestapo in 1938, his sister Herta appealed to his father's achievements. Robert Ernst was indeed released. But he had to undertake to leave the country within 24 hours. Robert Ernst fled to Switzerland.3 And from there on to the USA. There he would meet his sister again after the war. Herta had married Mendel Greif, a native of Galicia, in Bregenz in 1938 and fled with him to France. Greif was deported from there to Auschwitz and survived the death camp badly marked and starved.4

To enforce their new tasks, the "border police commissariat" had the entire spectrum of National Socialist persecution measures at its disposal, up to and including deportation to a concentration camp. But they also included the possibility of using “aggravated interrogation methods”, which meant nothing less than torture. In addition, “protective custody” was imposed, whereby unpopular persons were detained in prison in the upper town of Bregenz or transferred to Feldkirch or Innsbruck.5 Joseph Schreieder, who was transferred to the occupied Netherlands in the summer of 1940 as head of the department for espionage affairs, was followed in the next few years by several men who often changed quickly.6 Schreieder and his successors, often known only by their surnames, interrogated more than 10,000 people during this period. At least 7,000 people, among them about 1,500 Vorarlbergers, were also imprisoned in the prison in Bregenz Oberstadt.7

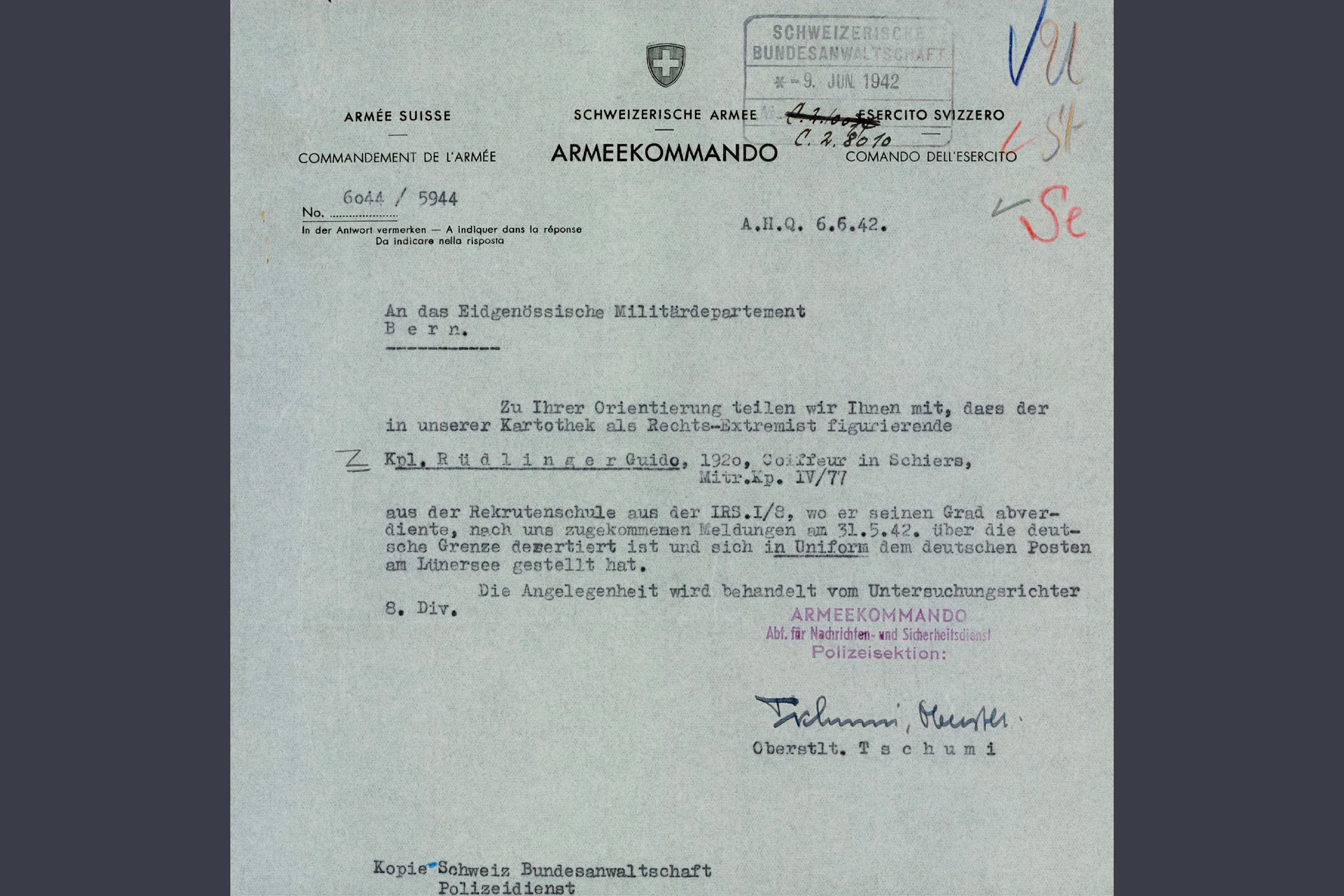

In 1942, when a total of almost 4,000 border guards were on duty in Vorarlberg, some Swiss also made it over the mountain passes along the border, the other way around.8 They, too, first ended up at the border police station in Bregenz Römerstraße – even if they had completely different reasons for their illegal crossing. On the night of 1 June 1942, for example, 21-year-old Guido Rüdlinger, who until then had done his military service in Switzerland, succeeded in doing so. The self-confessed right-wing radical and anti-Semite, himself an active member of the National Socialist “Eidgenössische Sammlung”, had “reported to the German border guard at Lake Lünersee in full military gear”. He subsequently joined the Waffen-SS. In August 1945 he returned to Switzerland, where he was immediately taken into custody. The next day, he willingly provided information about other Swiss who had served in the Waffen SS and also reported on his escape to Vorarlberg at the Lünersee:

“From there I went to Brand, Bludenz, Bregenz. There I was in prison for 12 days. A Gestapo officer named Kintzel interrogated me here. I volunteered for the Waffen SS and was then sent to the Panorama Home in Stuttgart. On 15 June 1942 I went to the Sennheim training camp in Alsace. [...] We also enjoyed racial-political instruction. (...) Already at the beginning of October I was sent to the front in Finland with about 200 men. Here I belonged to the 12th SS-Geb.Jäger Reg. Reinhard Heydrich.”9

Rüdlinger fought on the Russian front, was then trained as a high mountain hunter in Tyrol and finally deployed in South Tyrol to capture and disarm Italian troops who had become enemies in the meantime. This was followed by missions in Norway and Denmark. His adventure finally ended in the Vosges Mountains with a serious wound and capture by the Americans. As early as 1942, he was sentenced in Switzerland “to 10 years in prison for escape, breach of duty and propaganda dangerous to the state [...]”. A prison sentence he indeed had to serve after his return in 1945.

In the last months of the war, when the German defeat had long since been sealed, members of the Wehrmacht and the SS again attempted to cross into Switzerland in the opposite direction via Vorarlberg. On the Swiss side, however, only a select few were allowed to cross the border.10 At the Gestapo in Bregenz, other priorities were already being set at that time, since they were aware of the latest events on the war front and abroad at an early stage. At the end of April, the border police station in Bregenz Römerstraße began to cover the traces of National Socialist crimes.11 When the Gestapo officers left Bregenz for the Arlberg mountain on 28 April, nothing was left of the documents relating to their seven years of terror. Everything was burnt.12

Recommended reading:

Meinrad Pichler, Nationalsozialismus in Vorarlberg. Opfer. Täter. Gegner. Innsbruck/Vienna 2012; Meinrad Pichler, „Das Bregenzer Gefangenenhaus während der NS-Diktatur“, in: Nationalsozialismus erinnern, ed. by Landeshauptstadt Bregenz, Bregenz 2021, pp. 209 - 223.

Links:

On the occasion of the Lake Constance Church Day 2002, a memorial path was installed in the city area of Bregenz with nine plaques commemorating people in Bregenz who resisted National Socialism or were victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecution.

https://www.erinnern.at/media/552bdd0f079b9d170c74c85f66e5dfb8/gedenkweg-pdf

[1] Meinrad Pichler, Nationalsozialismus in Vorarlberg. Opfer. Täter. Gegner. Innsbruck/Vienna 2012, pp. 78-79.

[2] Ibid., p. 77-79.

[3] Ibid., p. 187-88.

[4] Ibid., p. 188-89.

[5] Ibid., p. 90.

[6] Ibid, p. 79.

[7] Meinrad Pichler, “Das Bregenzer Gefangenenhaus während der NS-Diktatur“, in: Nationalsozialismus erinnern, ed. by Landeshauptstadt Bregenz, Bregenz 2021, pp. 209 - 223, here p. 215.

[8] Pichler, Nationalsozialismus, p. 269.

[9] Swiss Federal Archives, 1973/00017 Office of the Attorney General (Bern) (1915-1975), Rüdlinger, Guido, 1920.

[10] Pichler, Nationalsozialismus, p. 278.

[11] Ibid., p. 348.

[12] Ibid.

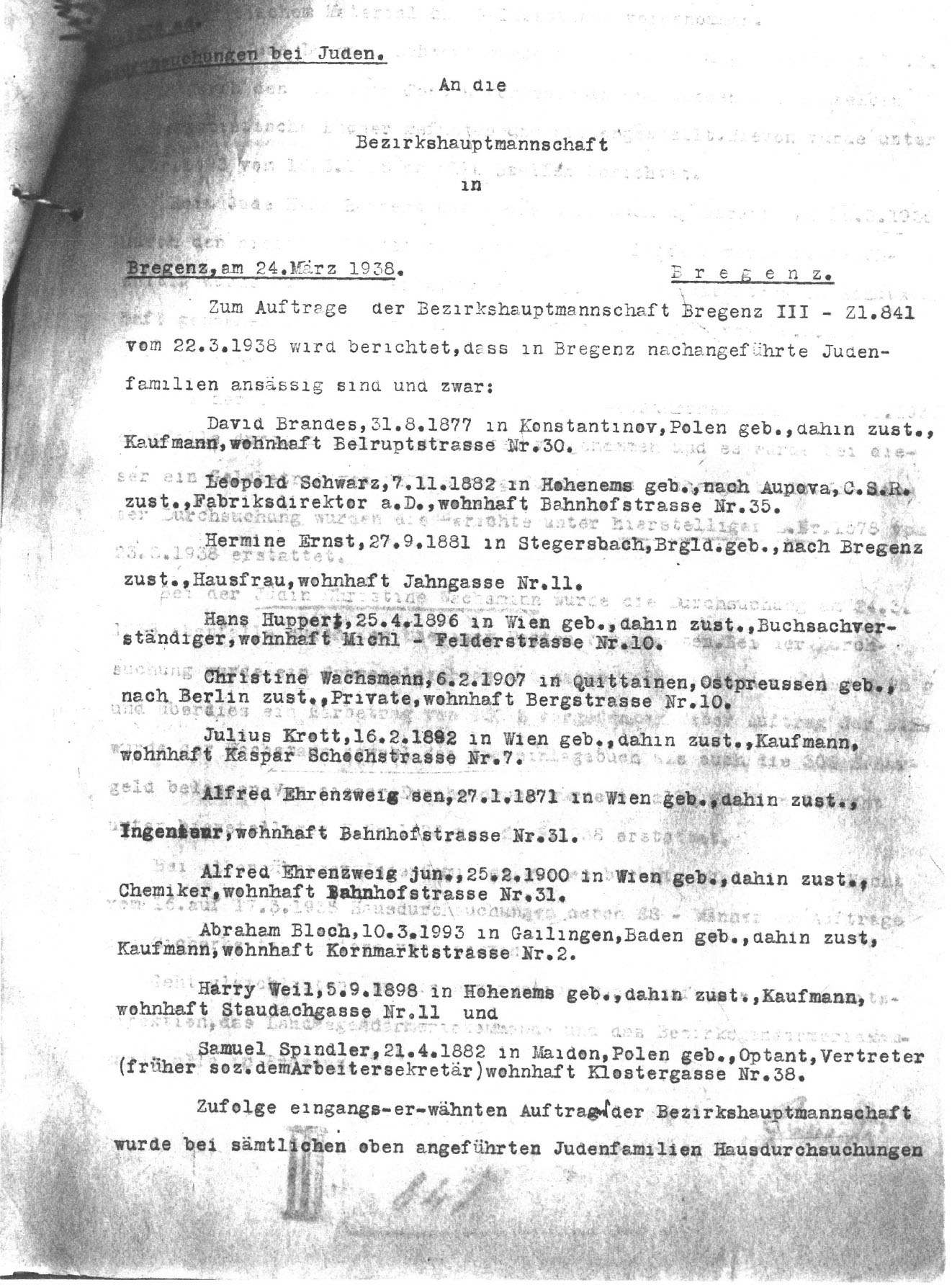

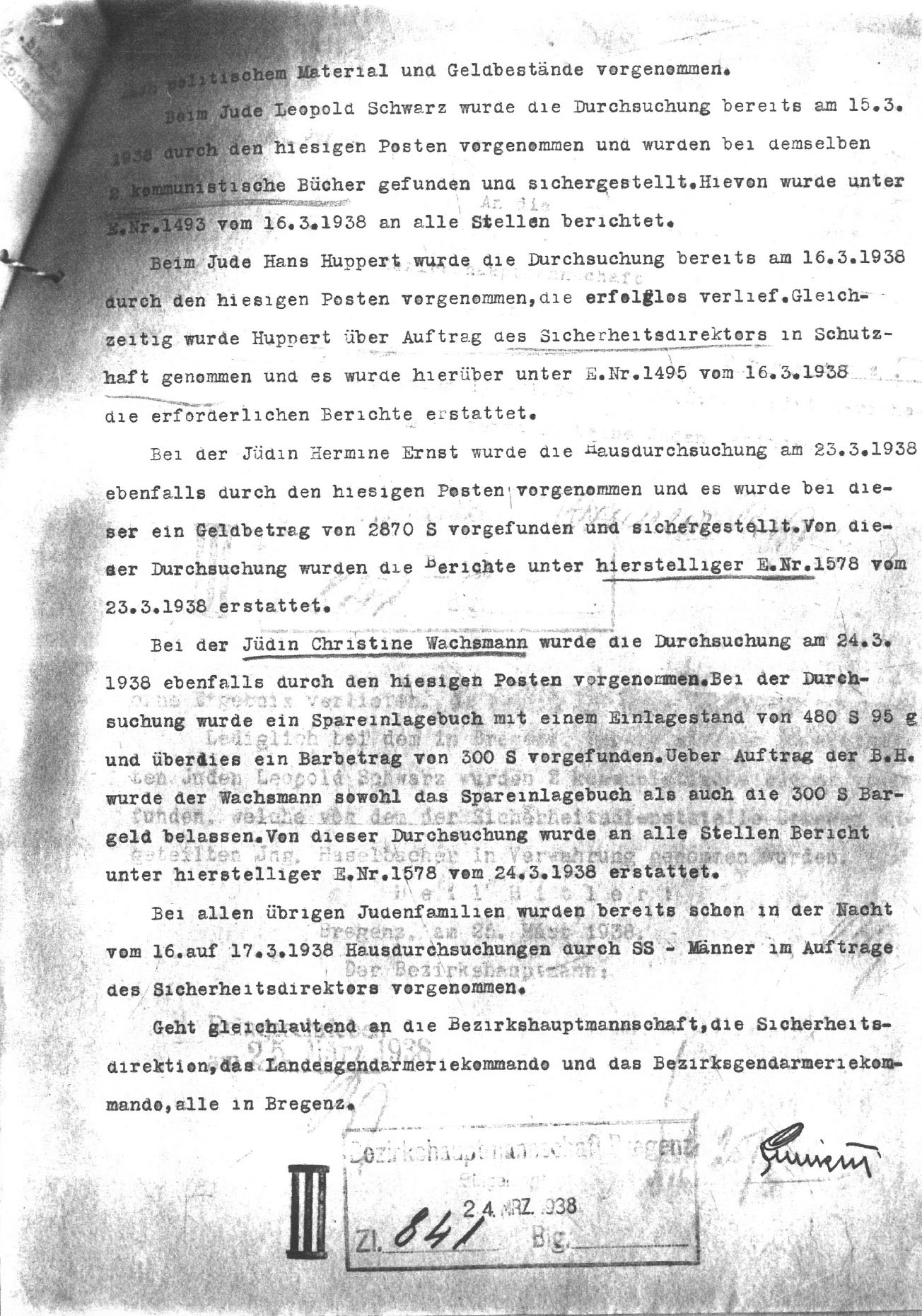

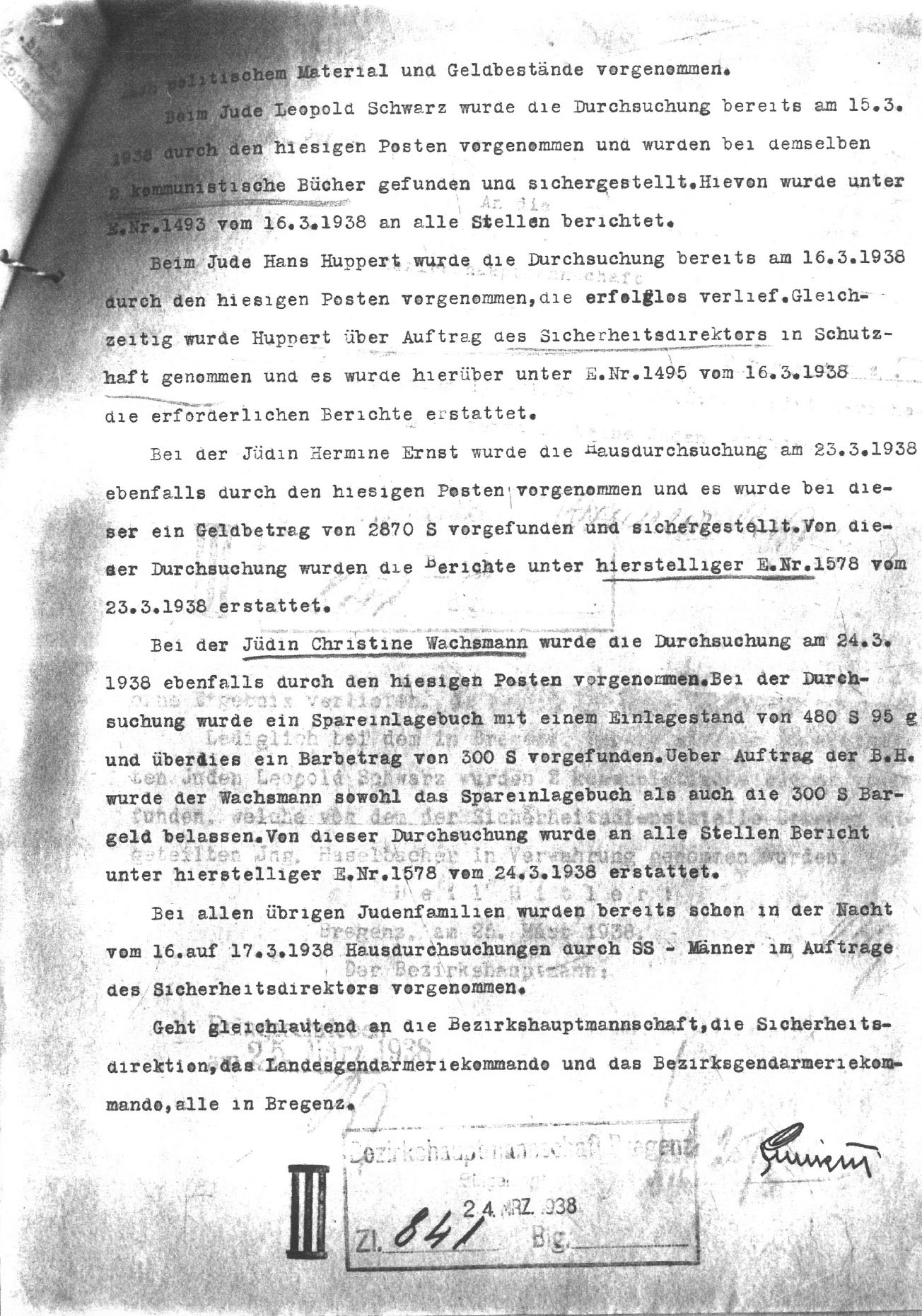

Report of the Gendarmerieposten Bregenz on house searches of Jews, to the Bezirkshauptmannschaft in Bregenz, March 24, 1938

Source: Vorarlberger Landesarchiv, Misc. Sch. 271

6 Border Police Commissariat

Interrogated by the Gestapo: Existences are decided at the Border Police Commissioners' Office

Bregenz, 1938 to 1945

After the so-called “Anschluss” of Austria to Nazi Germany, the Secret State Police, or Gestapo for short, was also organized in Vorarlberg in April 1938. Officially, the branch of the state persecution apparatus was called the “Bregenz Border Police Commissariat” and was subordinate to the state police headquarters in Innsbruck. Its headquarters were established at Römerstraße No. 7. After the conquest of France and the German invasion of Yugoslavia, the border with Switzerland was one of the last “windows into a free country”.1 This had an effect not least on the activities of the police, who from the autumn of 1938 tried to prevent border crossings into Switzerland by all means. For both across the Rhine and in the mountains, people who had been persecuted in the German Reich for racist and political reasons now tried to reach freedom this way. The main person responsible for surveillance was initially Joseph Schreieder, the first head of the border police command, who had been transferred from Munich first to Lindau and then on to Bregenz at the beginning of 1938.2

Robert Ernst was one of the first to be arrested by this newly formed Gestapo unit. Born in 1916, he had just completed his military service in the Bregenz barracks and, as a soldier in the previous Austrian army, refused to take the oath to the new “Führer”. His father Oskar Ernst, who came from Moravia, had opened several fashion shops in Vorarlberg from 1905 and soon moved to the provincial capital. As a soldier, he had soon returned wounded from the First World War - and became involved in the care of war-disabled people in the city hospital, for which he was honored by the Red Cross in 1916. Just three years later he died as a result of his war injury and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Hohenems.

After Robert's arrest by the Gestapo in 1938, his sister Herta appealed to his father's achievements. Robert Ernst was indeed released. But he had to undertake to leave the country within 24 hours. Robert Ernst fled to Switzerland.3 And from there on to the USA. There he would meet his sister again after the war. Herta had married Mendel Greif, a native of Galicia, in Bregenz in 1938 and fled with him to France. Greif was deported from there to Auschwitz and survived the death camp badly marked and starved.4

To enforce their new tasks, the "border police commissariat" had the entire spectrum of National Socialist persecution measures at its disposal, up to and including deportation to a concentration camp. But they also included the possibility of using “aggravated interrogation methods”, which meant nothing less than torture. In addition, “protective custody” was imposed, whereby unpopular persons were detained in prison in the upper town of Bregenz or transferred to Feldkirch or Innsbruck.5 Joseph Schreieder, who was transferred to the occupied Netherlands in the summer of 1940 as head of the department for espionage affairs, was followed in the next few years by several men who often changed quickly.6 Schreieder and his successors, often known only by their surnames, interrogated more than 10,000 people during this period. At least 7,000 people, among them about 1,500 Vorarlbergers, were also imprisoned in the prison in Bregenz Oberstadt.7

In 1942, when a total of almost 4,000 border guards were on duty in Vorarlberg, some Swiss also made it over the mountain passes along the border, the other way around.8 They, too, first ended up at the border police station in Bregenz Römerstraße – even if they had completely different reasons for their illegal crossing. On the night of 1 June 1942, for example, 21-year-old Guido Rüdlinger, who until then had done his military service in Switzerland, succeeded in doing so. The self-confessed right-wing radical and anti-Semite, himself an active member of the National Socialist “Eidgenössische Sammlung”, had “reported to the German border guard at Lake Lünersee in full military gear”. He subsequently joined the Waffen-SS. In August 1945 he returned to Switzerland, where he was immediately taken into custody. The next day, he willingly provided information about other Swiss who had served in the Waffen SS and also reported on his escape to Vorarlberg at the Lünersee:

“From there I went to Brand, Bludenz, Bregenz. There I was in prison for 12 days. A Gestapo officer named Kintzel interrogated me here. I volunteered for the Waffen SS and was then sent to the Panorama Home in Stuttgart. On 15 June 1942 I went to the Sennheim training camp in Alsace. [...] We also enjoyed racial-political instruction. (...) Already at the beginning of October I was sent to the front in Finland with about 200 men. Here I belonged to the 12th SS-Geb.Jäger Reg. Reinhard Heydrich.”9

Rüdlinger fought on the Russian front, was then trained as a high mountain hunter in Tyrol and finally deployed in South Tyrol to capture and disarm Italian troops who had become enemies in the meantime. This was followed by missions in Norway and Denmark. His adventure finally ended in the Vosges Mountains with a serious wound and capture by the Americans. As early as 1942, he was sentenced in Switzerland “to 10 years in prison for escape, breach of duty and propaganda dangerous to the state [...]”. A prison sentence he indeed had to serve after his return in 1945.

In the last months of the war, when the German defeat had long since been sealed, members of the Wehrmacht and the SS again attempted to cross into Switzerland in the opposite direction via Vorarlberg. On the Swiss side, however, only a select few were allowed to cross the border.10 At the Gestapo in Bregenz, other priorities were already being set at that time, since they were aware of the latest events on the war front and abroad at an early stage. At the end of April, the border police station in Bregenz Römerstraße began to cover the traces of National Socialist crimes.11 When the Gestapo officers left Bregenz for the Arlberg mountain on 28 April, nothing was left of the documents relating to their seven years of terror. Everything was burnt.12

Recommended reading:

Meinrad Pichler, Nationalsozialismus in Vorarlberg. Opfer. Täter. Gegner. Innsbruck/Vienna 2012; Meinrad Pichler, „Das Bregenzer Gefangenenhaus während der NS-Diktatur“, in: Nationalsozialismus erinnern, ed. by Landeshauptstadt Bregenz, Bregenz 2021, pp. 209 - 223.

Links:

On the occasion of the Lake Constance Church Day 2002, a memorial path was installed in the city area of Bregenz with nine plaques commemorating people in Bregenz who resisted National Socialism or were victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecution.

https://www.erinnern.at/media/552bdd0f079b9d170c74c85f66e5dfb8/gedenkweg-pdf

[1] Meinrad Pichler, Nationalsozialismus in Vorarlberg. Opfer. Täter. Gegner. Innsbruck/Vienna 2012, pp. 78-79.

[2] Ibid., p. 77-79.

[3] Ibid., p. 187-88.

[4] Ibid., p. 188-89.

[5] Ibid., p. 90.

[6] Ibid, p. 79.

[7] Meinrad Pichler, “Das Bregenzer Gefangenenhaus während der NS-Diktatur“, in: Nationalsozialismus erinnern, ed. by Landeshauptstadt Bregenz, Bregenz 2021, pp. 209 - 223, here p. 215.

[8] Pichler, Nationalsozialismus, p. 269.

[9] Swiss Federal Archives, 1973/00017 Office of the Attorney General (Bern) (1915-1975), Rüdlinger, Guido, 1920.

[10] Pichler, Nationalsozialismus, p. 278.

[11] Ibid., p. 348.

[12] Ibid.

Report of the Gendarmerieposten Bregenz on house searches of Jews, to the Bezirkshauptmannschaft in Bregenz, March 24, 1938

Source: Vorarlberger Landesarchiv, Misc. Sch. 271