Emilie Haas> March 28, 1943

9 Emilie Haas

Paper war over permanent asylum. Emilie Haas and the Swiss authorities

Höchst - St. Gall, March 28, 1943

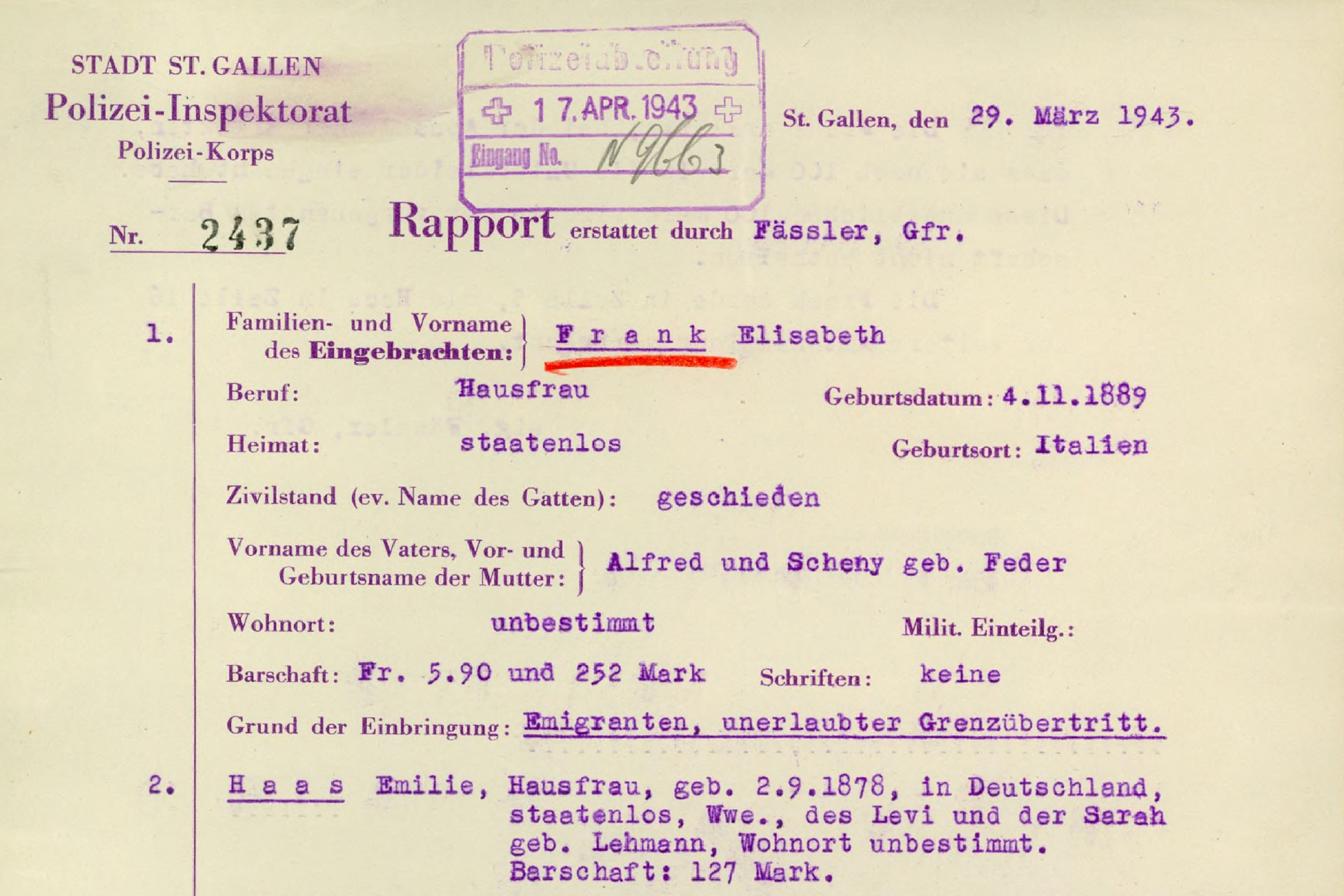

“Haas Emilie, housewife, born 2.9.1878, in Germany, stateless, widow, (daughter) of Levi and Sarah née Lehmann, place of residence undetermined. Cash: 127 Marks. Reason for deposit: Emigrant, unauthorized border crossing.”[1]

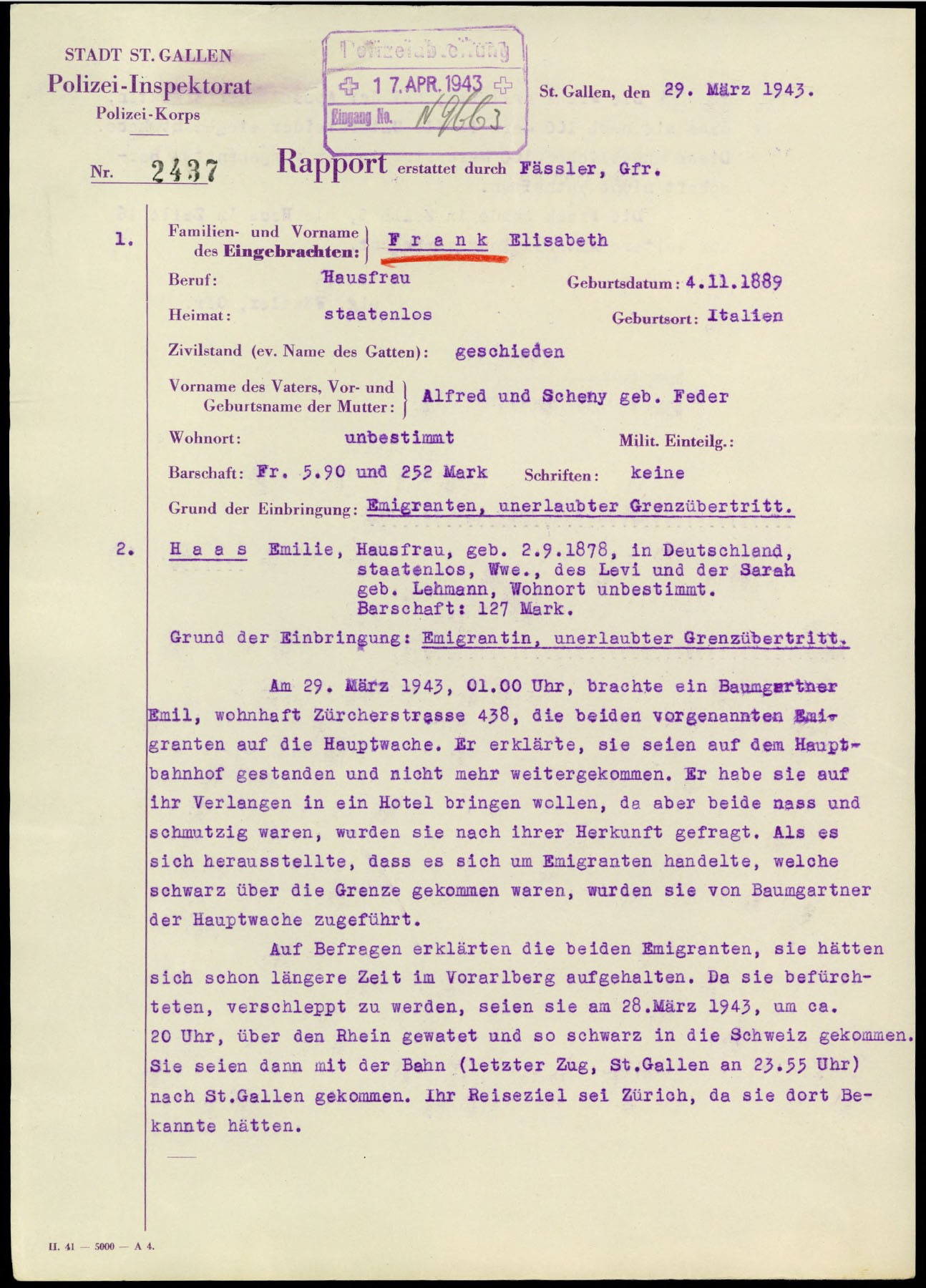

In the night of 28-29 March, two women, Emilie Haas and Elisabeth Frank are locked up in cells 5 and 16 of the St. Gall city police. Police officer Fässler writes his report.

“On March 29, 1943, 01.00 a.m., a Baumgartner Emil, resident at Zürcherstrasse 438, brought the two aforementioned emigrants to the Hauptwache. He explained that they had been at the main railway station and could not get any further. He had wanted to take them to a hotel at their request, but as they were both wet and dirty, they were asked about their origin. When it turned out that they were emigrants who had illegally come across the border, Baumgartner took them to the main police station.

When questioned, the two emigrants explained that they had been in Vorarlberg for a long time. As they feared being deported, they had waded across the Rhine on March 28, 1943, at about 8 p.m., and thus entered Switzerland illegally.”

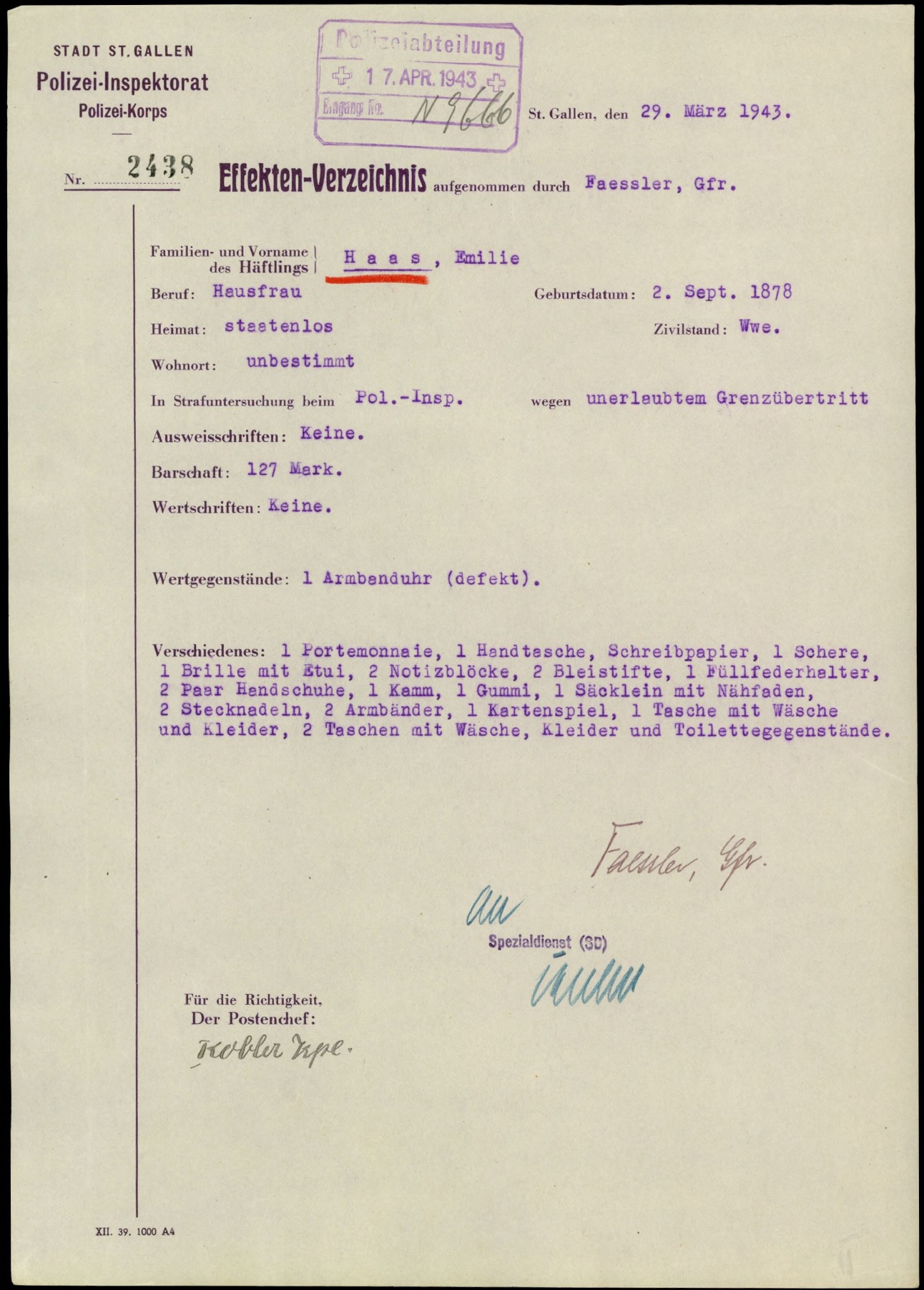

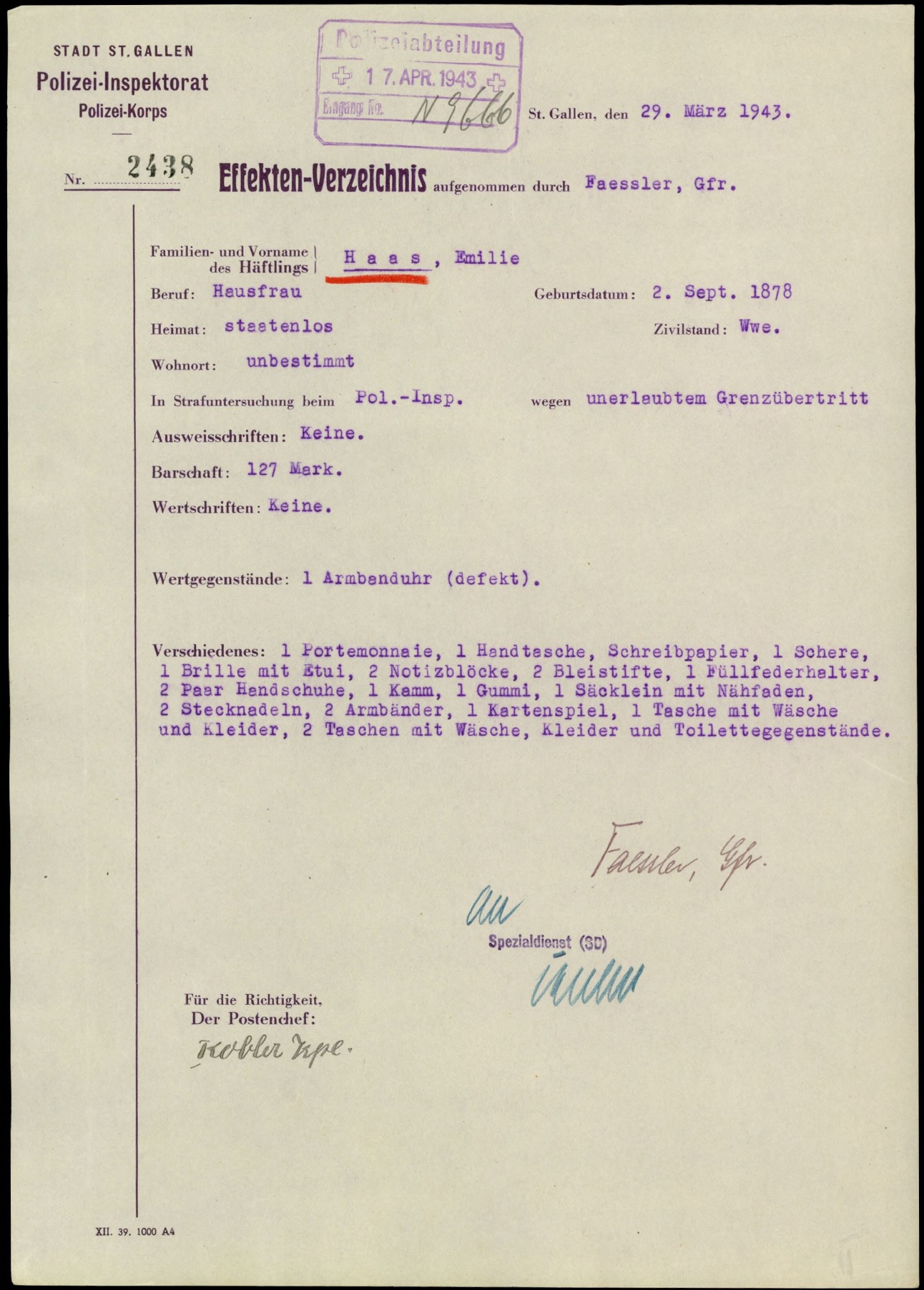

Emilie Haas has with her:

“Valuables: 1 wristwatch (defective). Miscellaneous: 1 wallet, 1 handbag, writing paper, 1 pair of scissors, 1 pair of glasses with case, 2 notepads, 2 pencils, 1 fountain pen, 2 pairs of gloves, 1 comb, 1 rubber, 1 small bag with sewing thread, 2 pins, 2 bracelets, 1 pack of cards. 1 bag with laundry and clothes, 2 bags with laundry, clothes and toiletries.” [2]

This is all she has to start a new life in Switzerland.

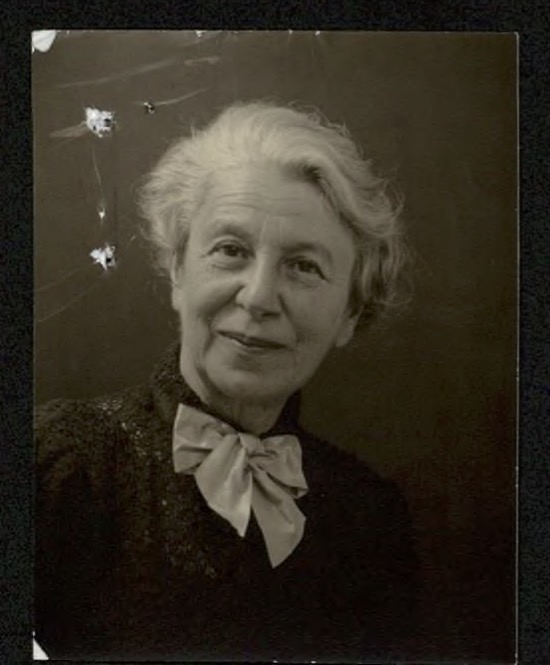

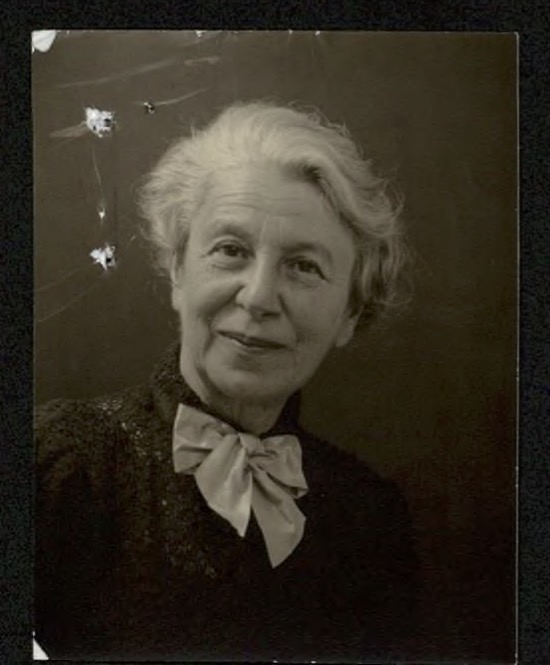

Emilie Haas, 1943

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Dossier Emilie Haas (E4264#1985/197#453*)

Emilie Haas had already fled Krefeld in June 1942 after receiving orders to report for deportation on 14 June. The transport to which she was ordered departs on 15 June with 1003 people from the Rhineland to Majdanek, where some men are selected for work, and from there to the Sobibor extermination camp with more than 900 condemned to death.[3]

Emilie Haas went into hiding. A non-Jewish acquaintance, the dentist Heinrich Kipphardt, who as a Social Democrat had himself been in a concentration camp twice, places her with a farmer in Sauerland under a false name as a harvest helper. In October, she changes hiding places, pretends to be a bomb victim and does housework for another family. But the risk becomes higher and higher.

Kipphardt makes contact with her cousin Elisabeth Frank, who has been in hiding for months as a helper with farmers in Schruns in Vorarlberg. She too is using a false name. With a forged postal identity card, Emilie Haas finally travels to Bregenz in March 1943. She meets Frank and Kipphardt who has also travelled from Krefeld to help the women. A family in Bregenz accommodates the two. Then a family in Höchst. And a smuggler of refugees takes them to the border and helps them get through the waist-deep water of the old Rhine and through the barbed wire enclosure on the Swiss side. Then the two are on their own.

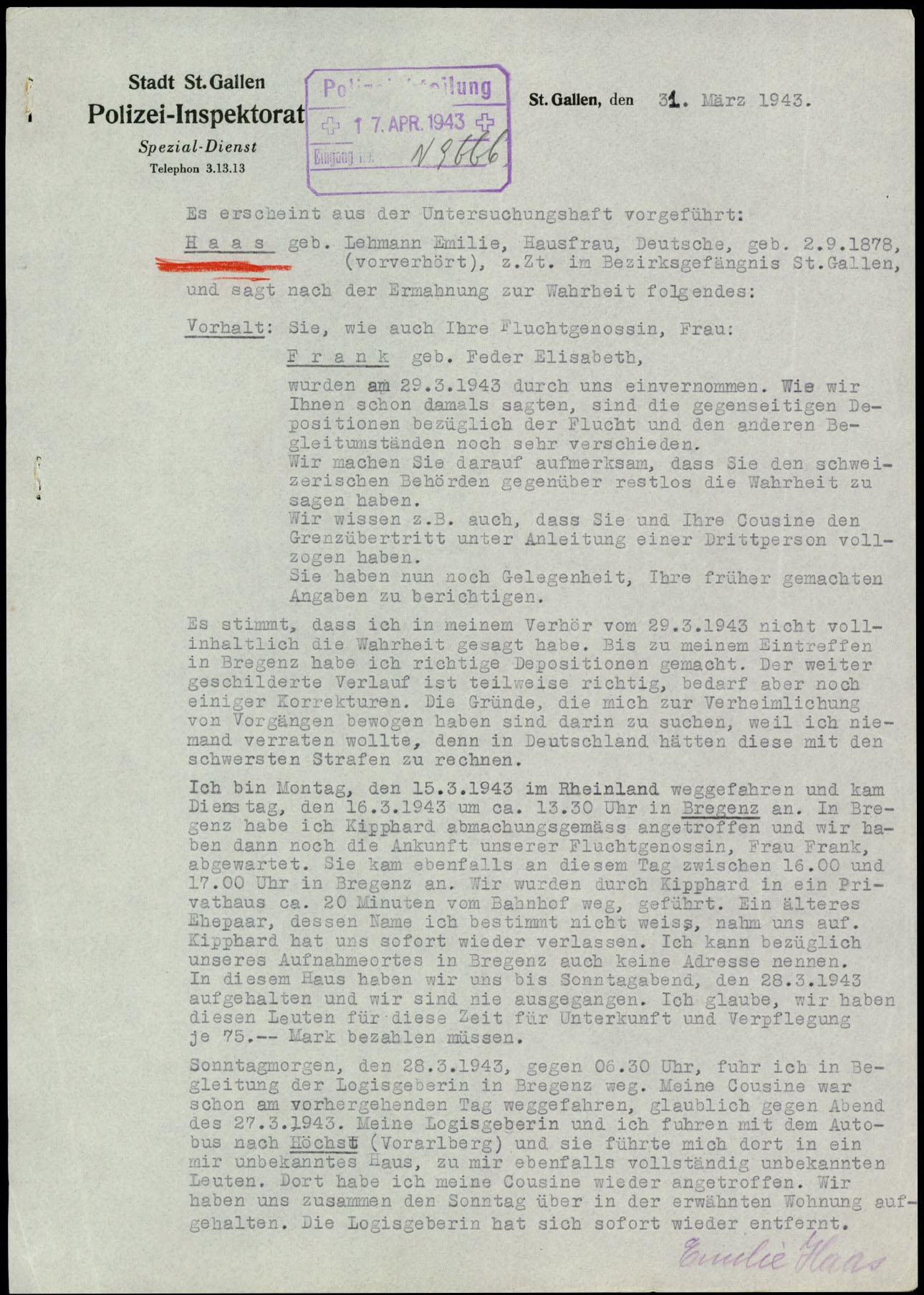

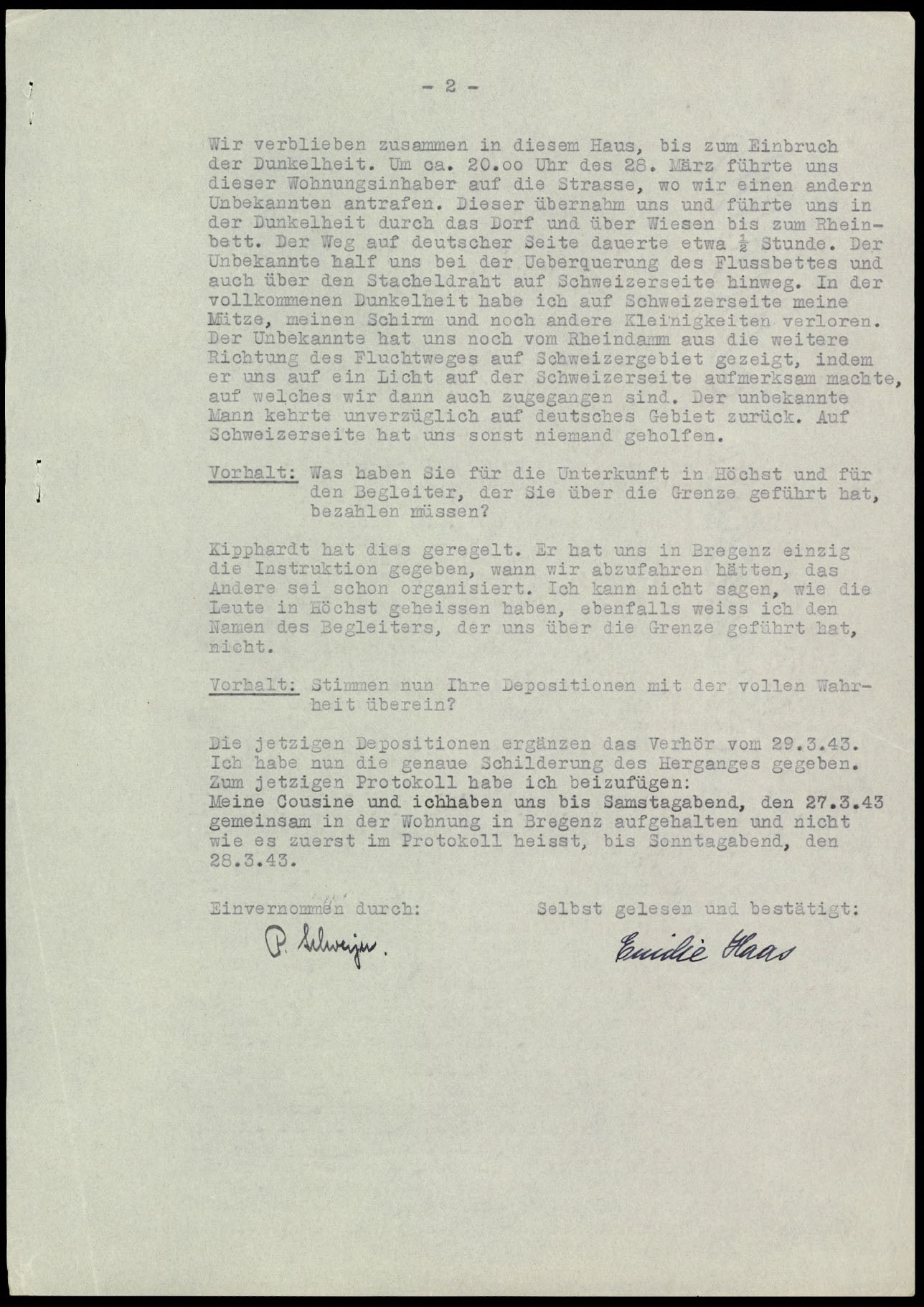

At the St. Gall police station they are interrogated several times. The officers notice contradictions in their statements. The women do not want to betray their helpers in Vorarlberg. Instead, they beg for their lives.

“I hope that I will be granted asylum here until I can leave for another country. Returning to Germany would mean my death.”

The two women are allowed to stay. From that moment on, the many documents that the Swiss Federal Archives have preserved their story are about their never-ending struggle for permanent asylum and an existence in Switzerland.

Initially interned in the Oberhelfenschwil refugee camp, the 65-year-old was classified as “not fit for a labor camp” in the spring – and transferred to private quarters in Sulgen in Thurgau. She will spend the rest of her life there.

Emilie Haas had already gotten to know the world a little. She had lived with her husband in Shanghai for many years until he died in 1931. There were no children. As a penniless widow, she returned to Krefeld to live on a small pension and a little rental income. Until she fled. In Switzerland as well, she remains a poor woman, whose care is now being fought over by various authorities, refugee aid and the Israelite poor relief organization. Her relatives in the USA, England, Italy and Uruguay are also asked to pay by the Swiss authorities. A trip to Rome to visit her nephews and a visit by her sister are held against her. The Thurgau poor relief authorities suspected social fraud.

In 1950, after a long paper war, Emilie Haas was granted permanent asylum, even though the authorities in Thurgau were still toying with the idea of deporting her to Germany in 1952. By then she had received emergency aid from there. She does not receive any reparations. The Aid Organization of the Protestant Churches of Switzerland finally took care of her and paid for her medical and hospital expenses. In the meantime, Emilie Haas is about to turn 80. On April 17, 1957 she dies during a visit to the doctor in St. Gall.

Her rescuer, Heinrich Kipphardt, also survived the end of the war by hiding as a deserter in the Siegerland region. Together with his son Heinar Kipphardt, the later politically engaged playwright and pioneer of documentary theatre....

[1] Police report 29.3.1943, St. Gall, Swiss Federal Archives.

[2] List of securities Emilie Haas, St. Gall, March 29, 1943, Dossier on Emilie Haas; Swiss Federal Archives.

[3] https://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de/list_ger_rhl_420615a.html, (13.1.2022).

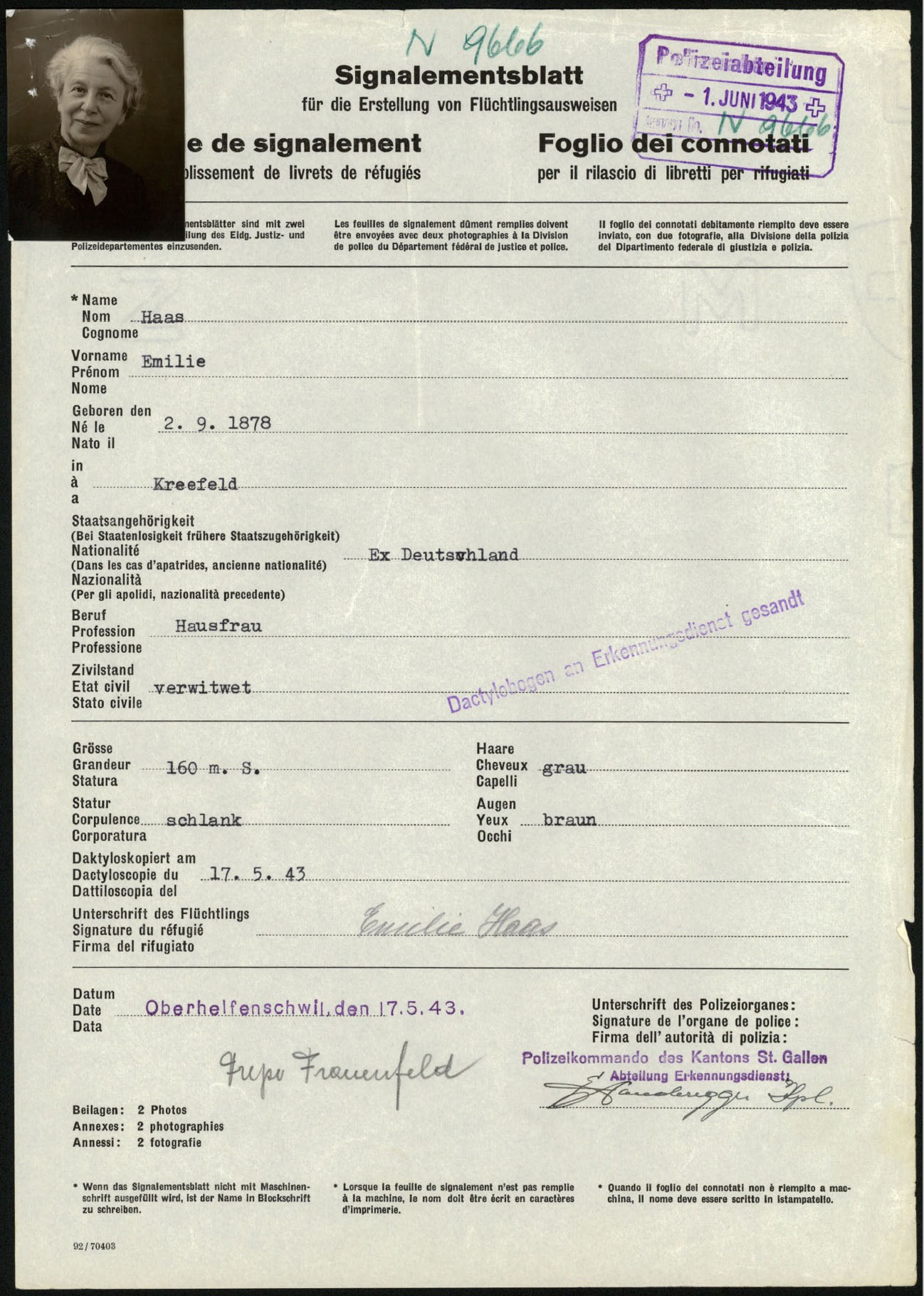

Report of the St. Gall police after the arrest of Emilie Haas and Elisabeth Frank, March 29, 1943. The Swiss Foreign Police's dossier on Emilie Haas runs to hundreds of pages.

Source: Swiss Federal Archives, Dossier Emilie Haas (E4264#1985/197#453*)

List of securities of Emilie Haas, March 29, 1943

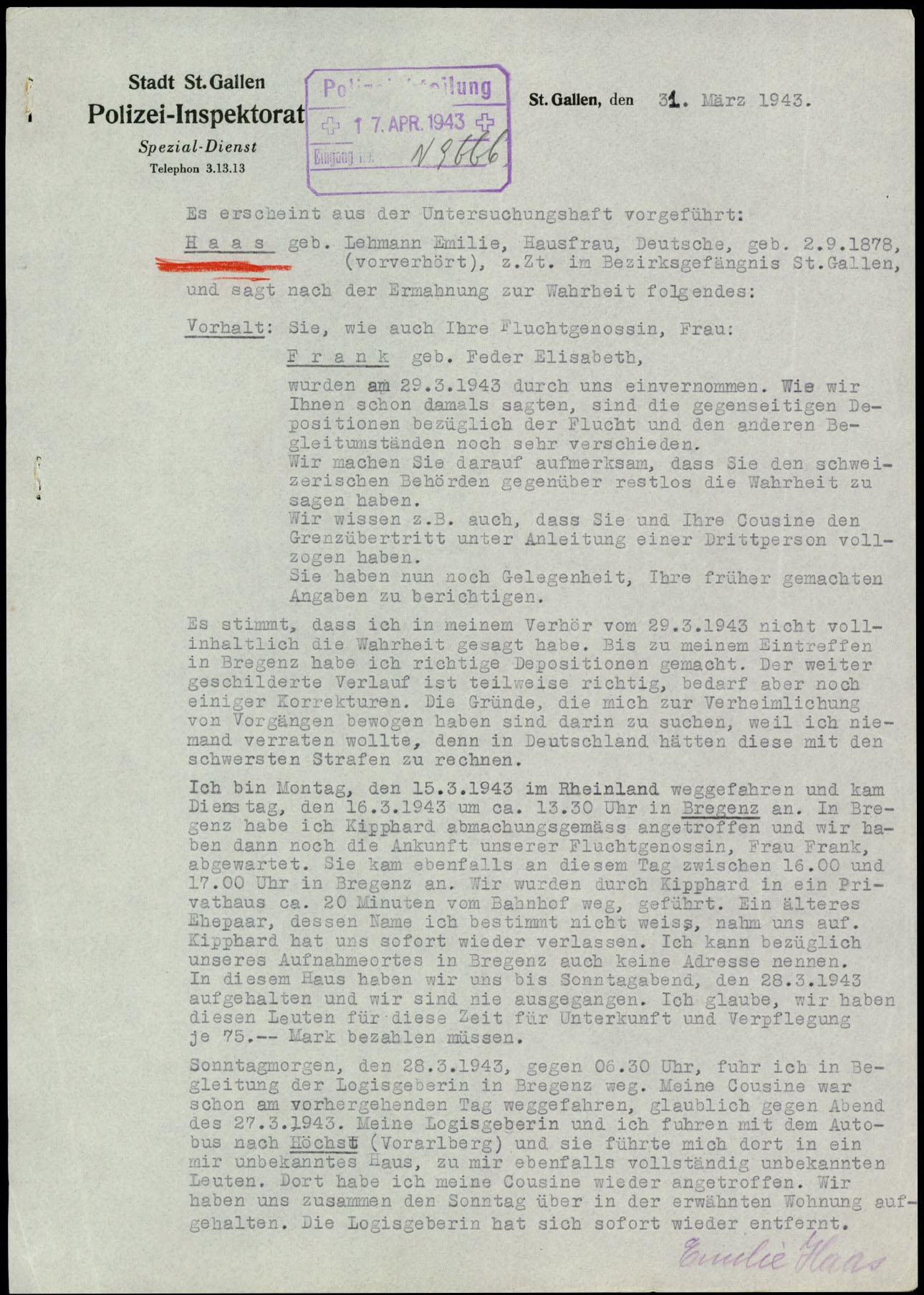

Second interrogation Emilie Haas, March 31, 1943

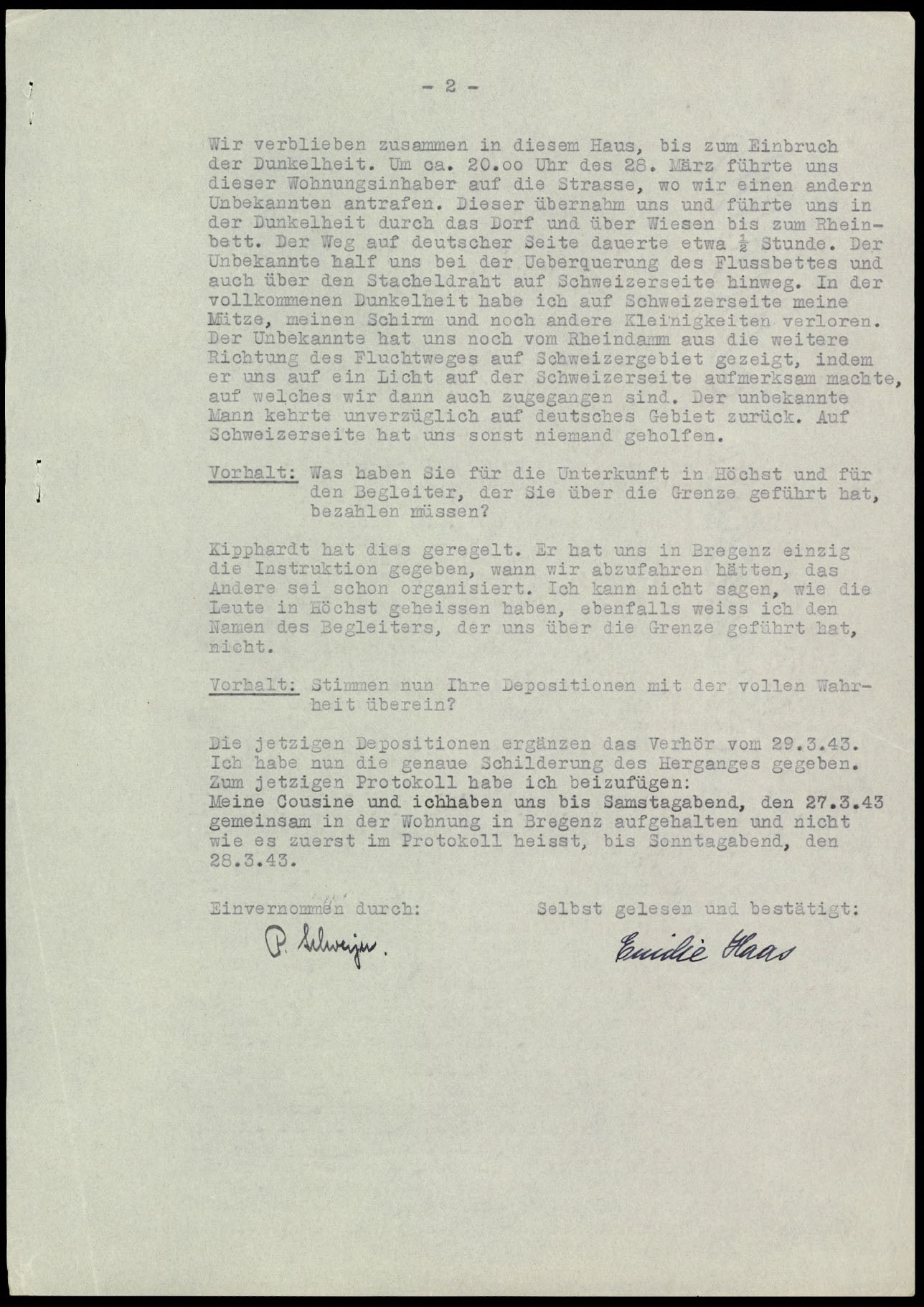

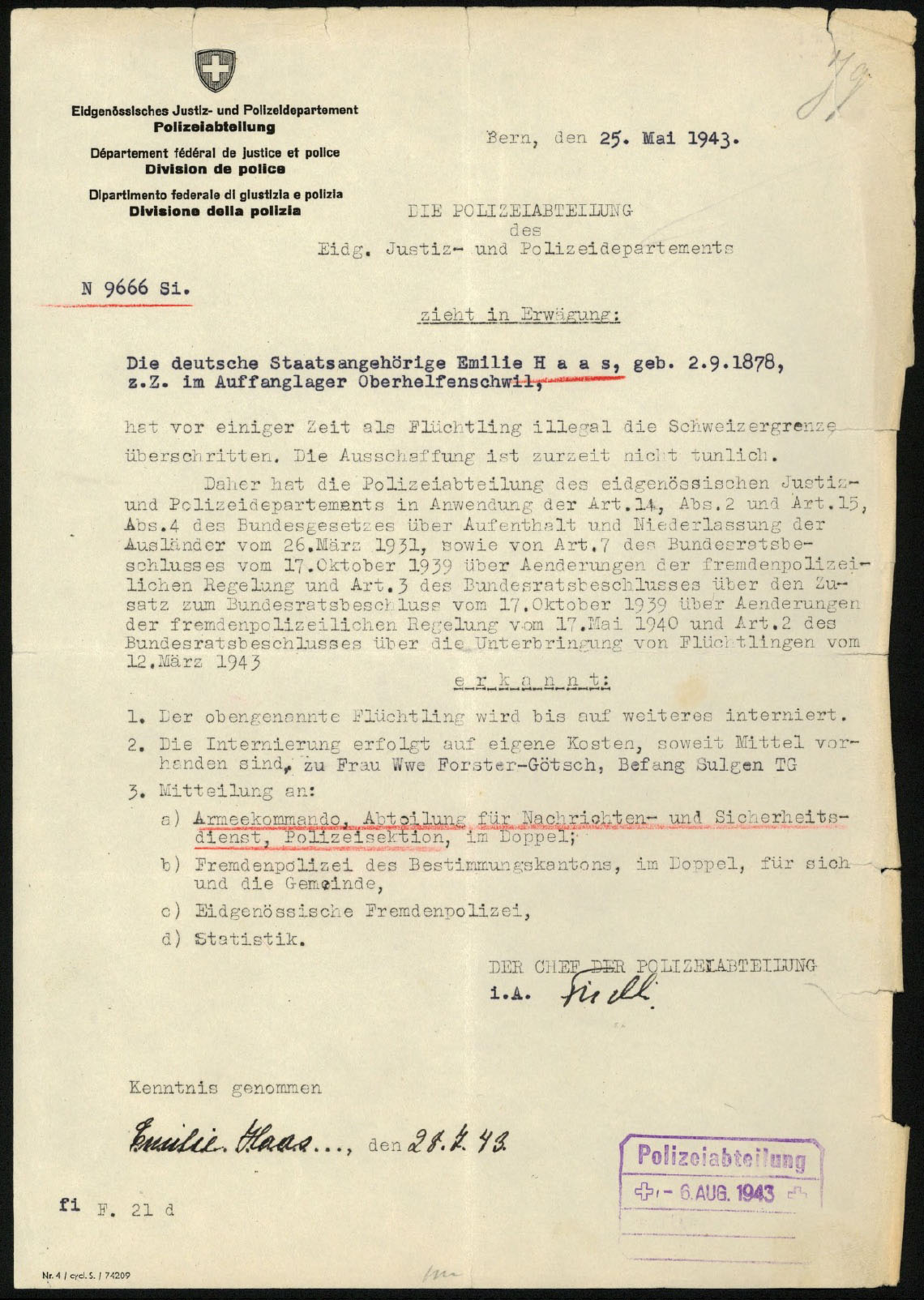

Decision of the Federal Department of Justice and Police on Internment, May 25, 1943

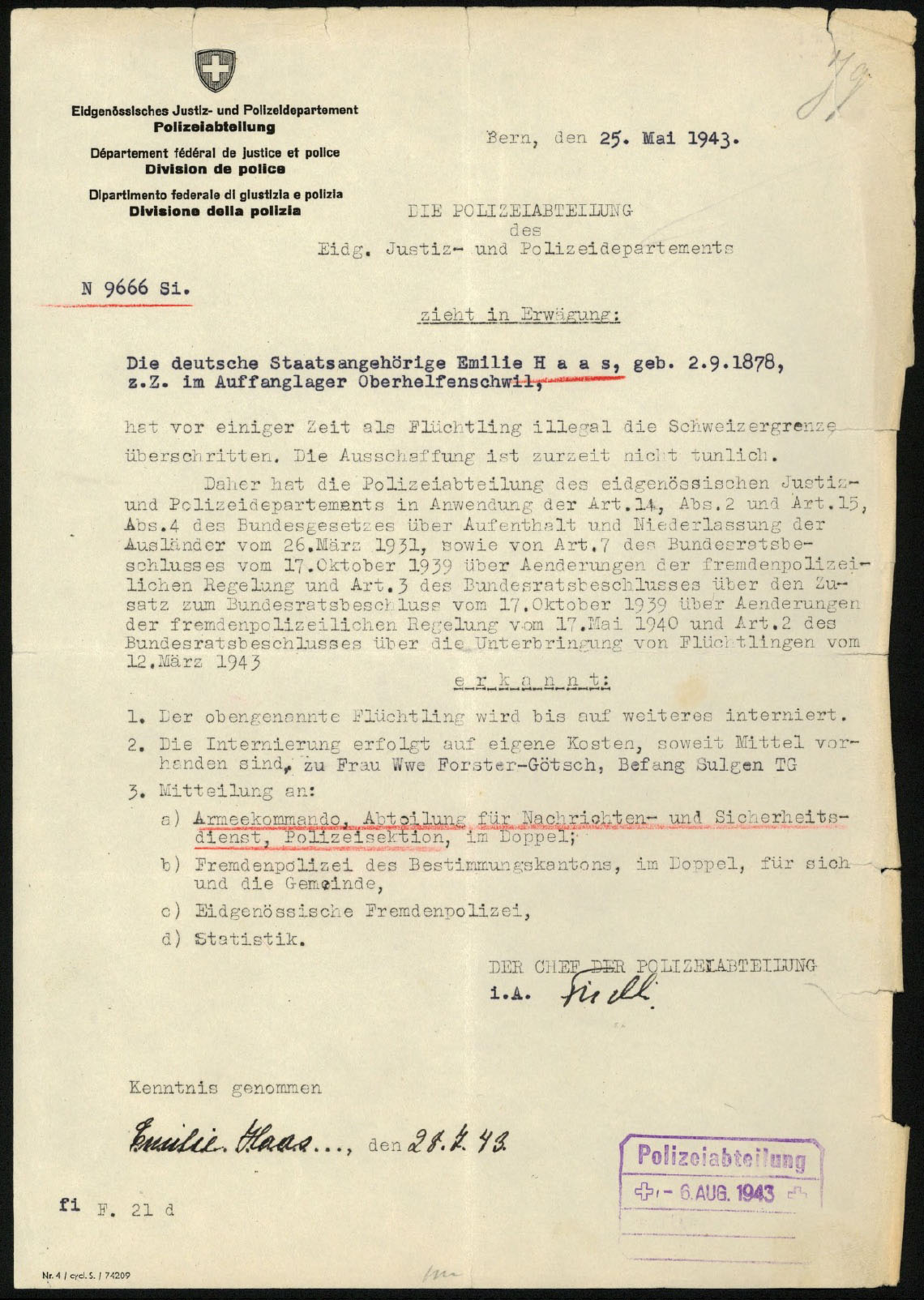

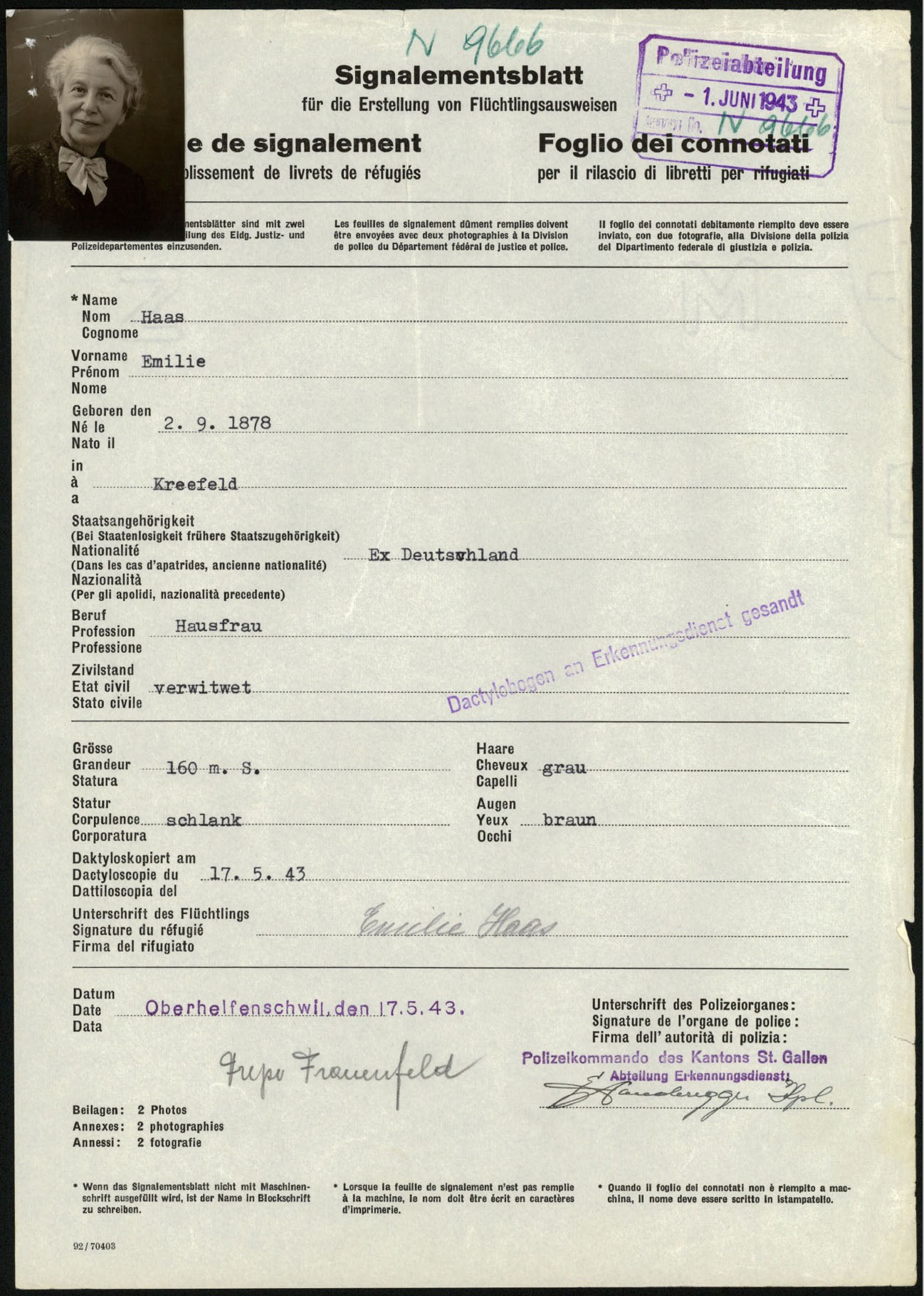

Signal sheet Emilie Haas, June 1, 1943

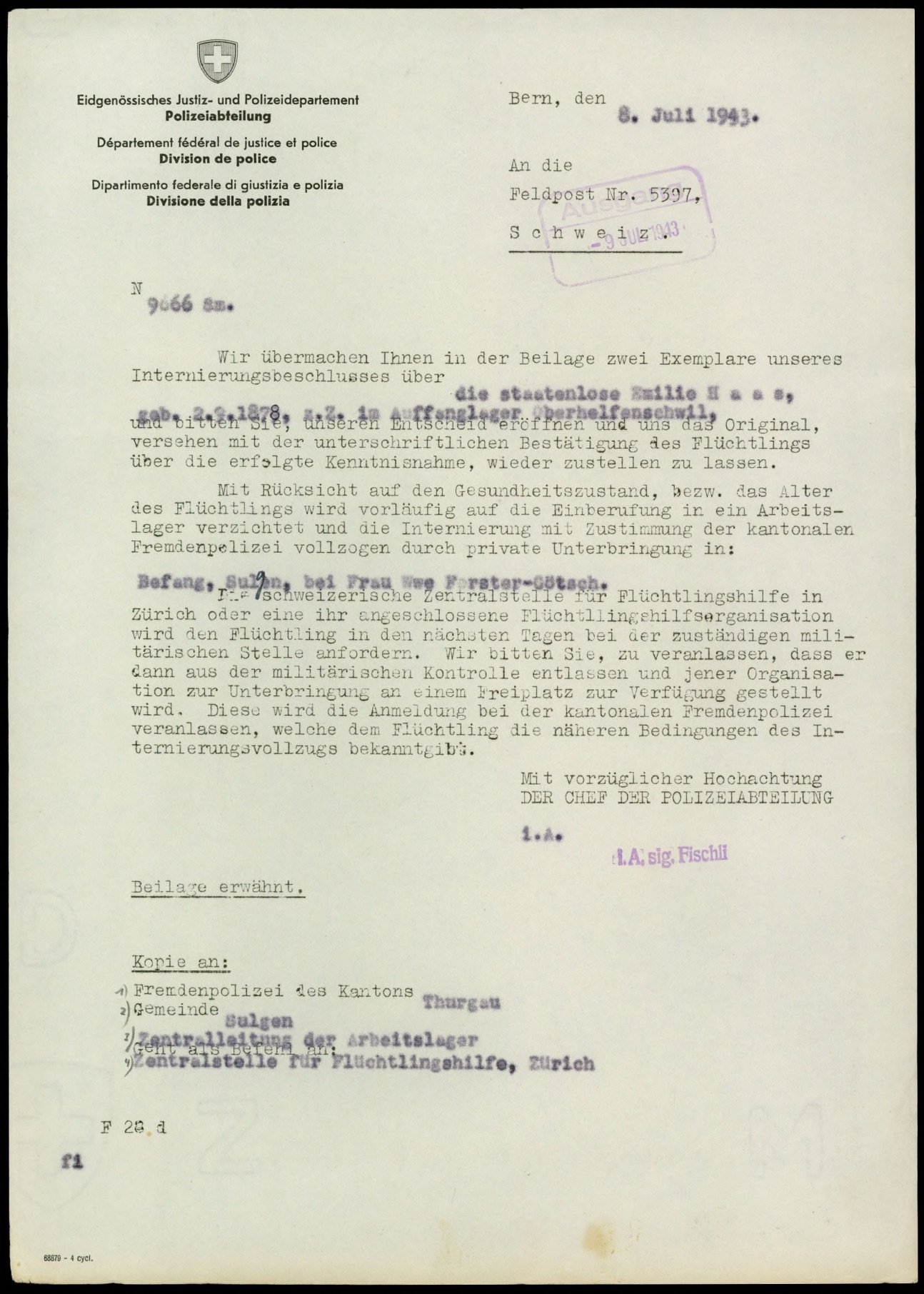

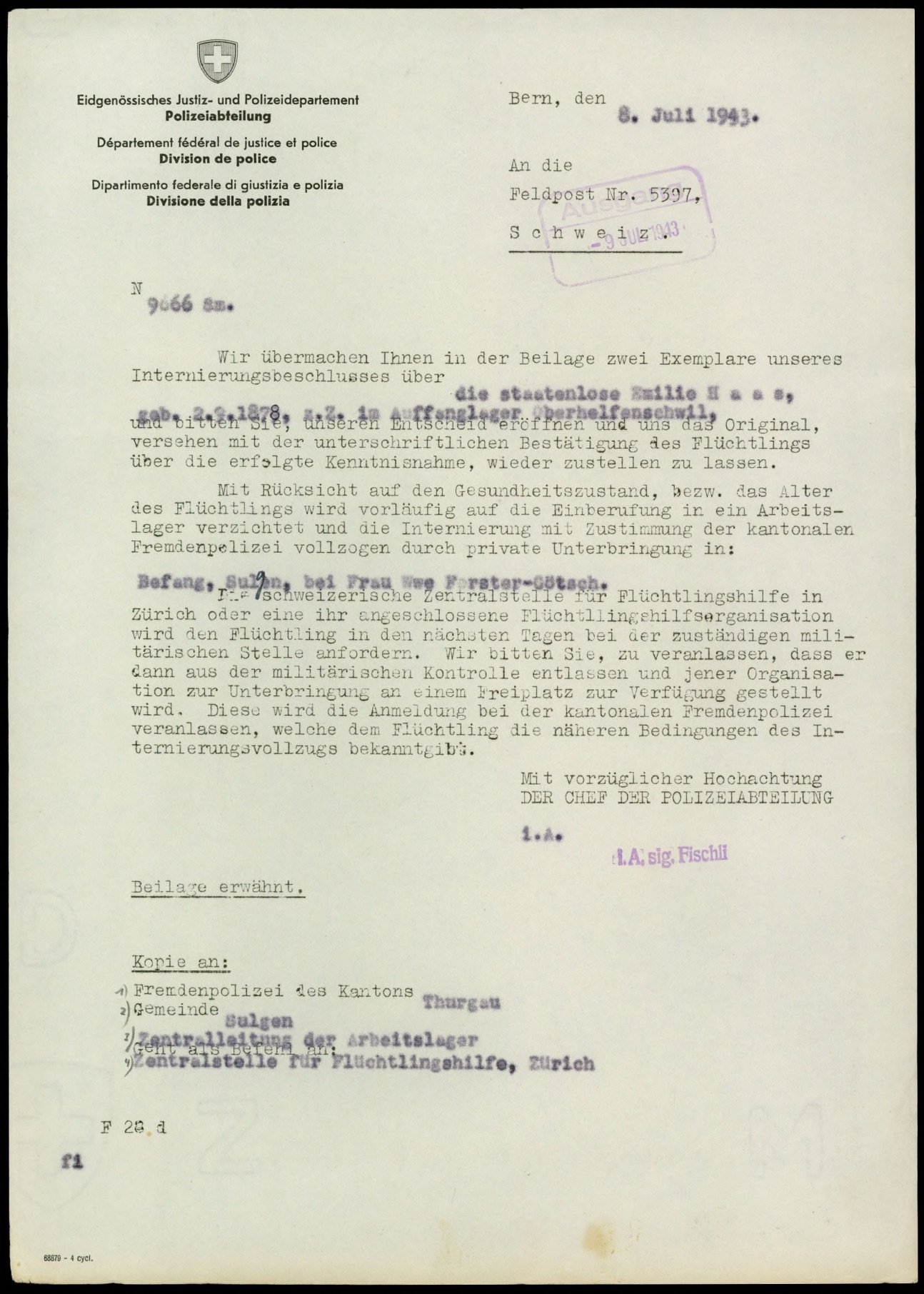

Letter accompanying the internment order, July 8, 1943

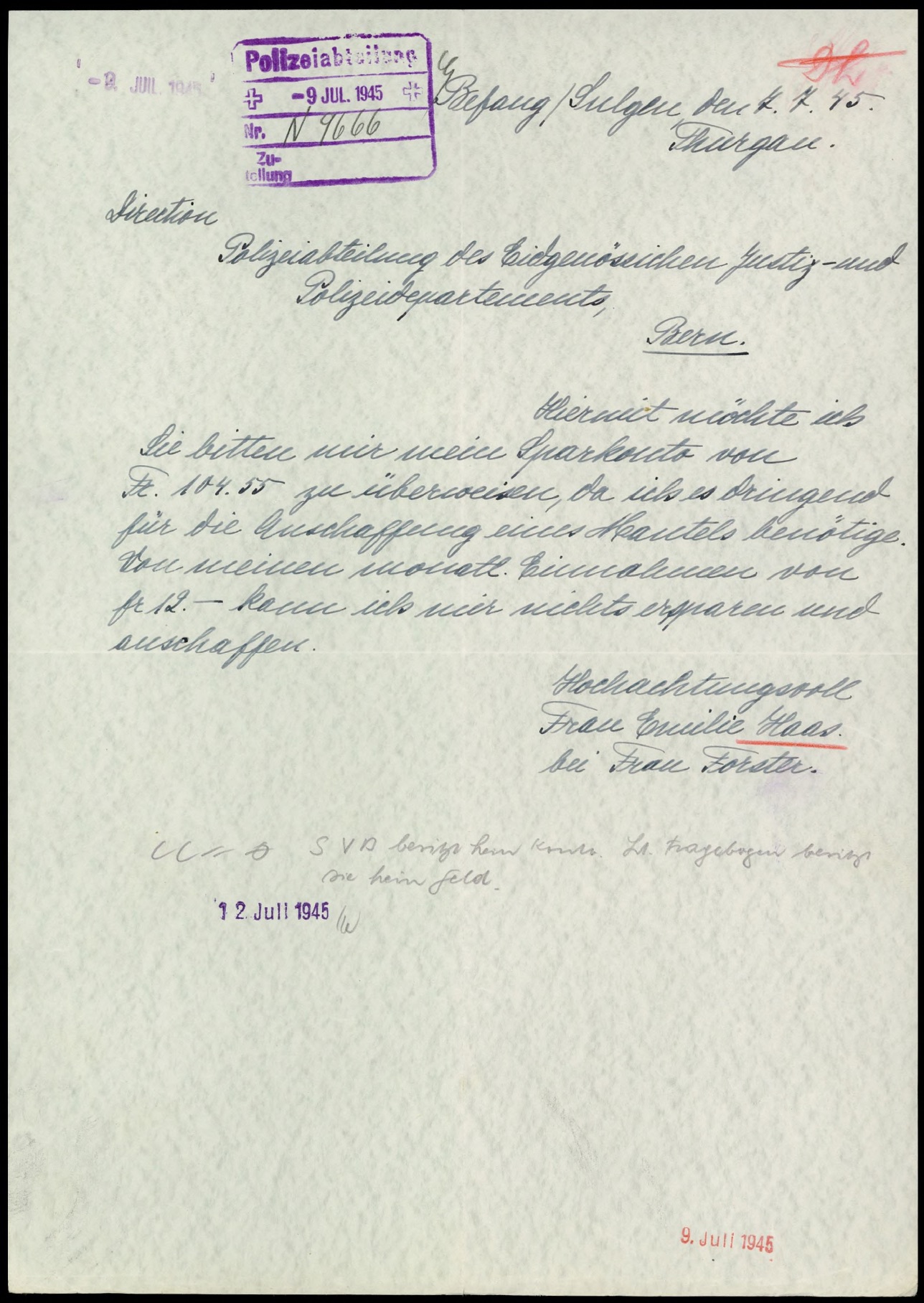

Request from Emilie Haas to release her savings account to purchase a coat, June 7, 1945

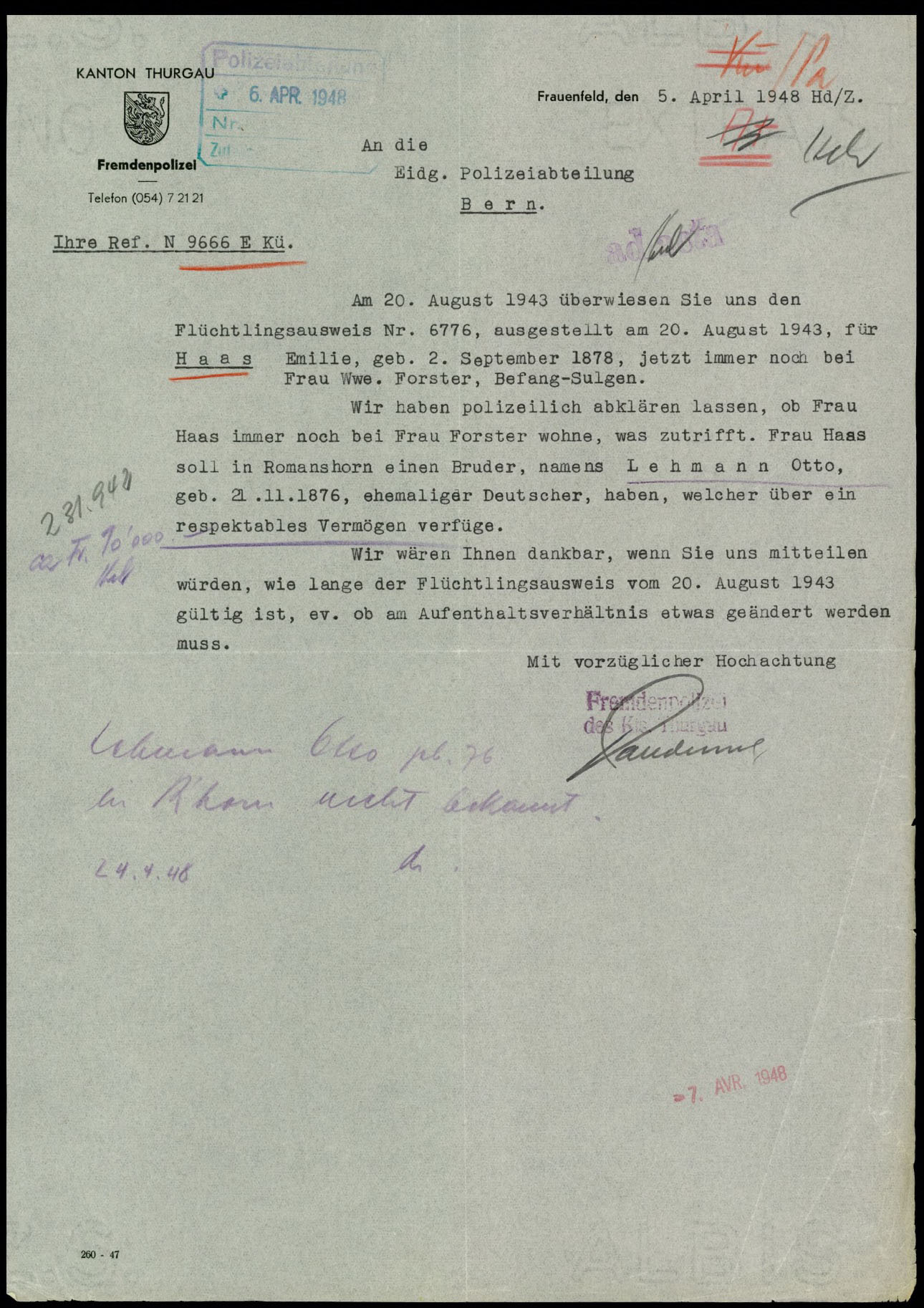

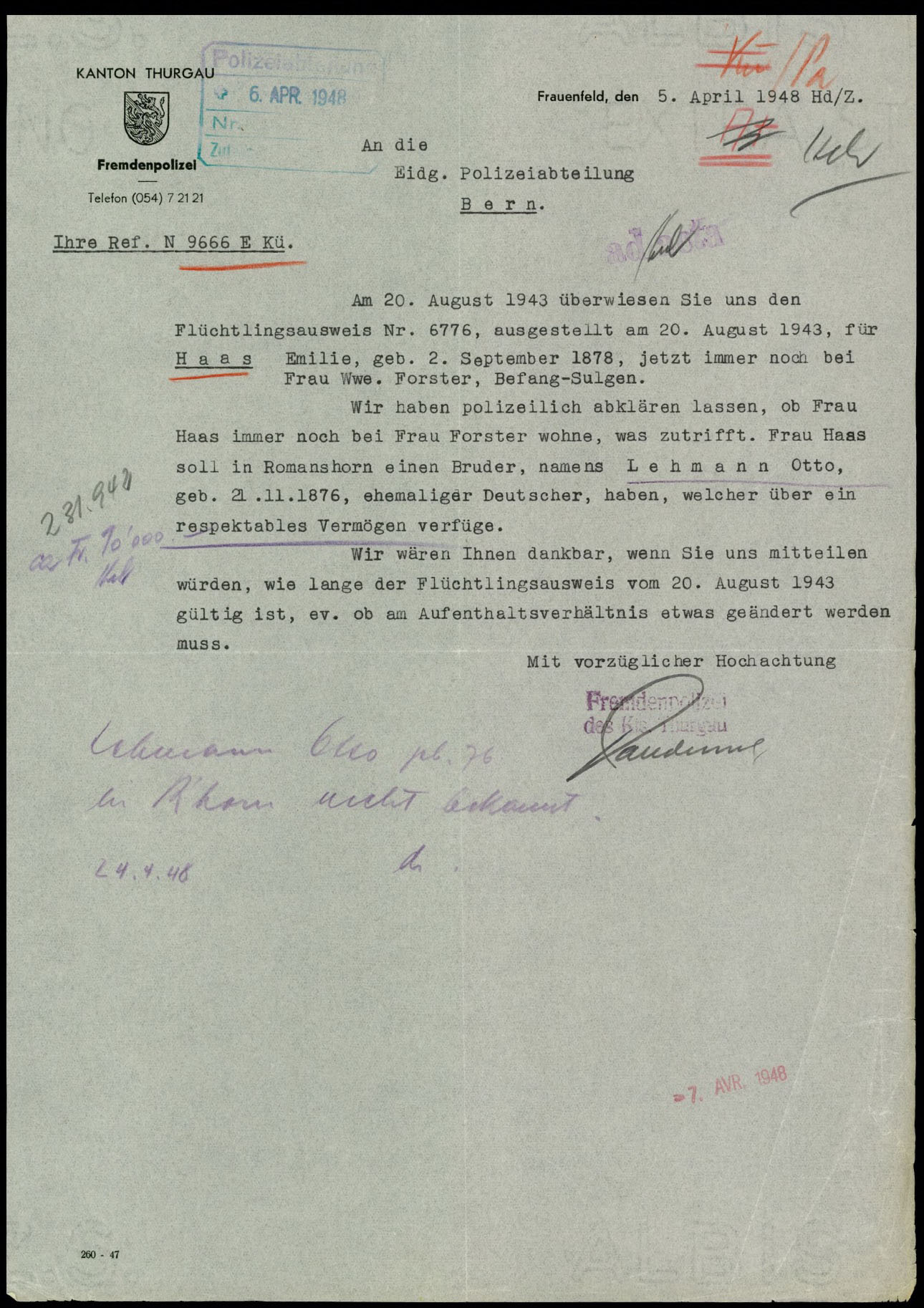

The canton of Thurgau claims that Emilie Haas has a wealthy brother in Romanshorn. But he lives in England and has long since lost his property. Letter to the Federal Police Department, April 5, 1948.

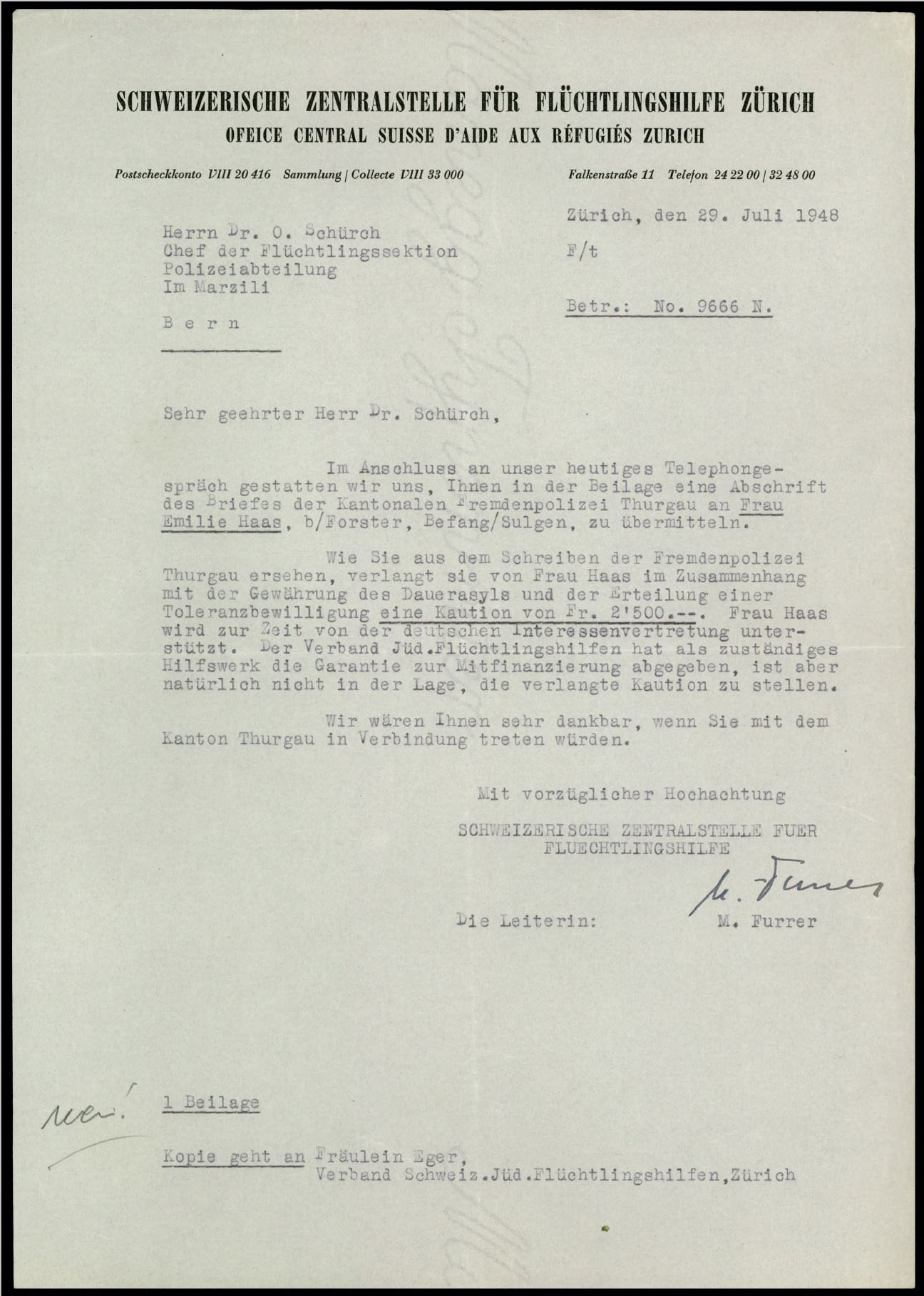

Swiss Refugee Aid is seeking relief for Emilie Haas' permanent asylum. Letter to the head of the refugee section of the police department in Bern, July 29, 1948.

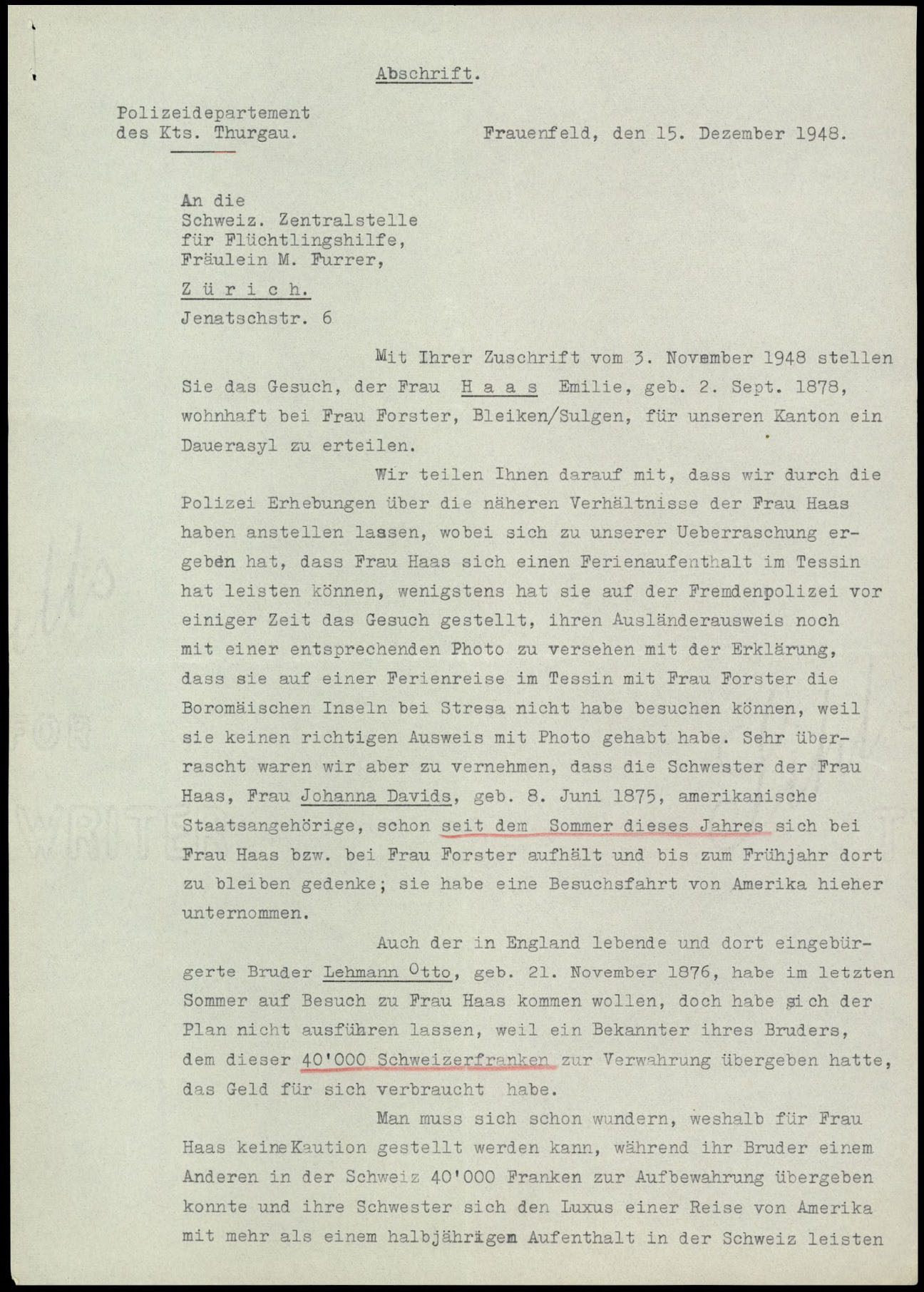

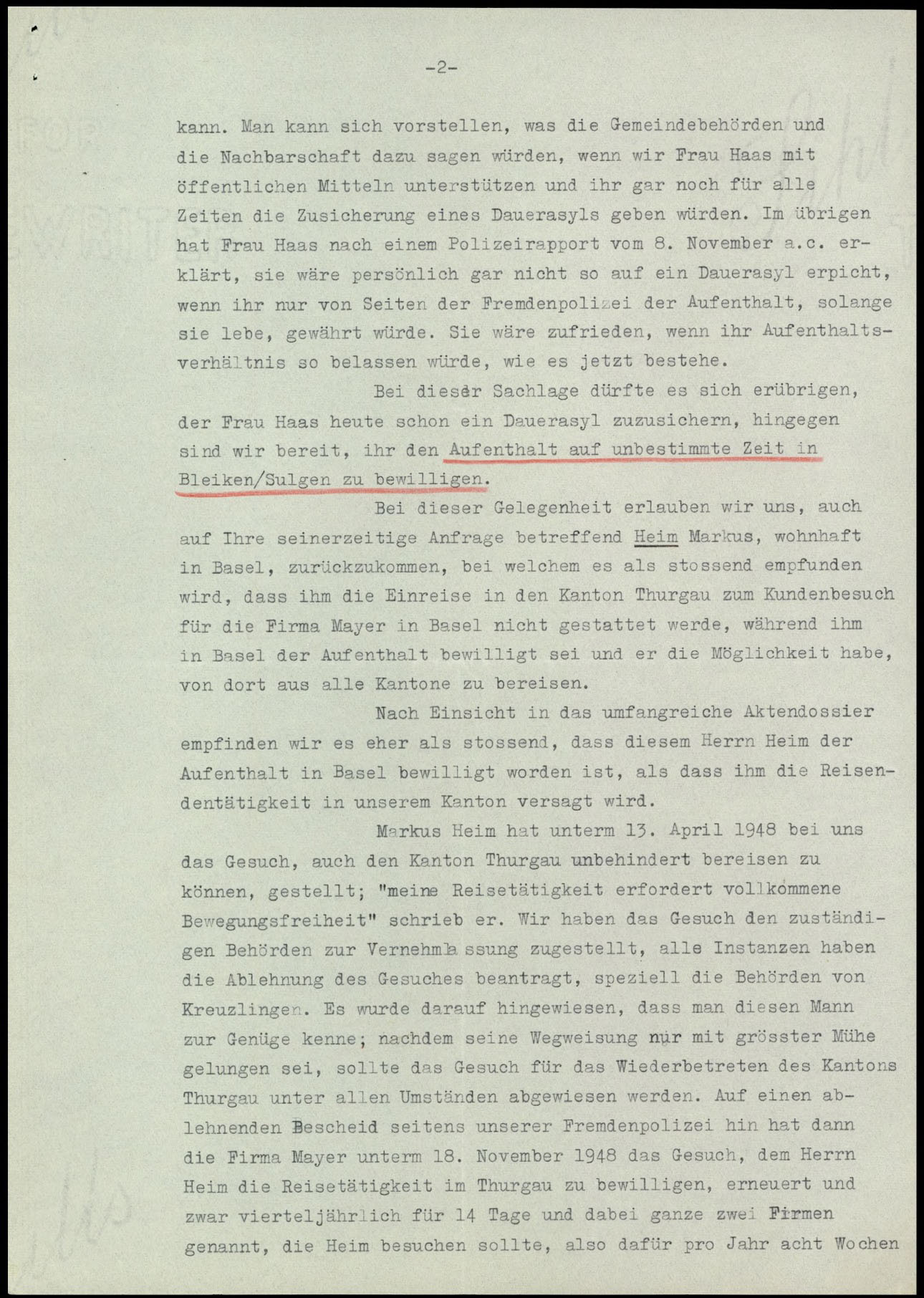

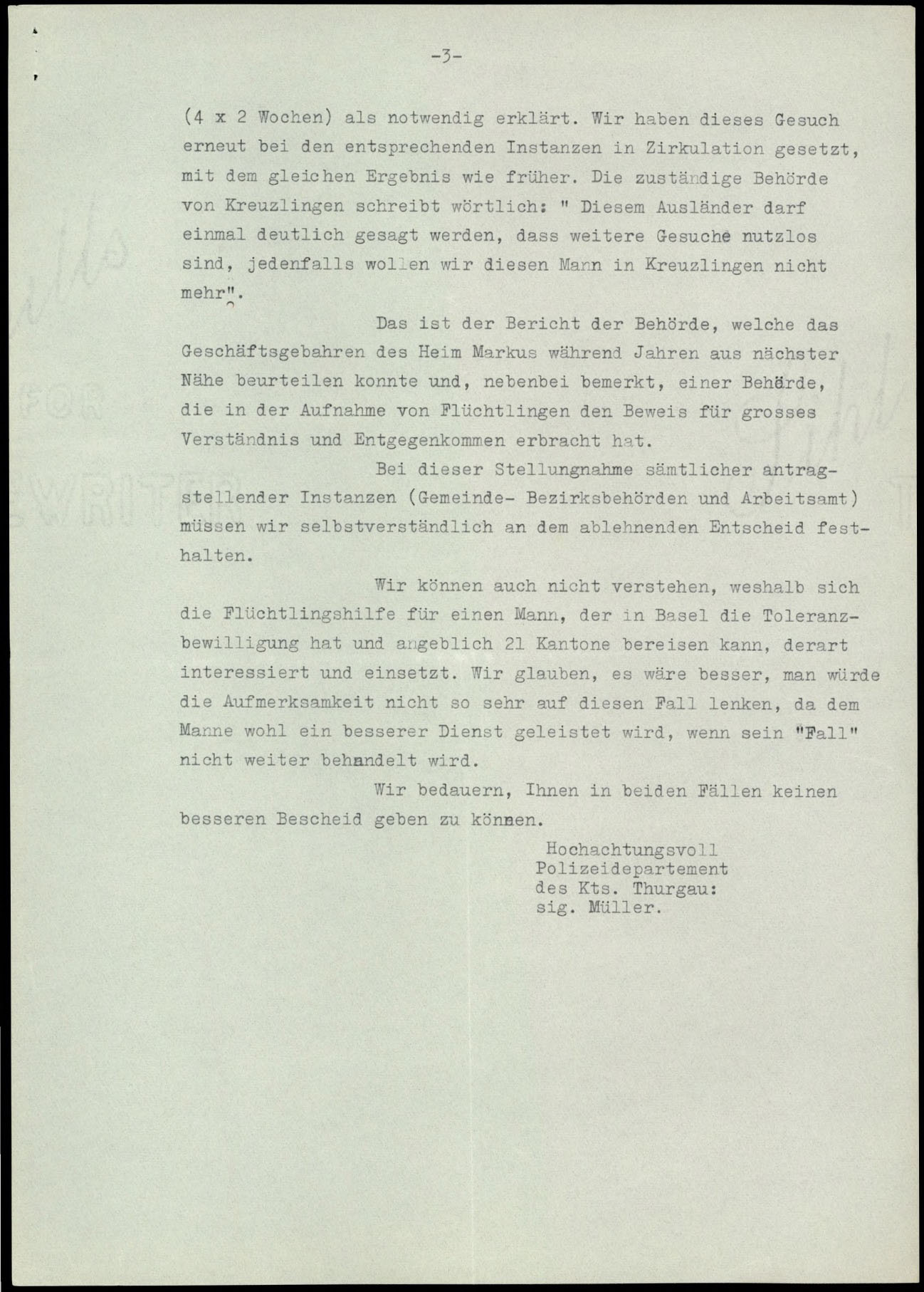

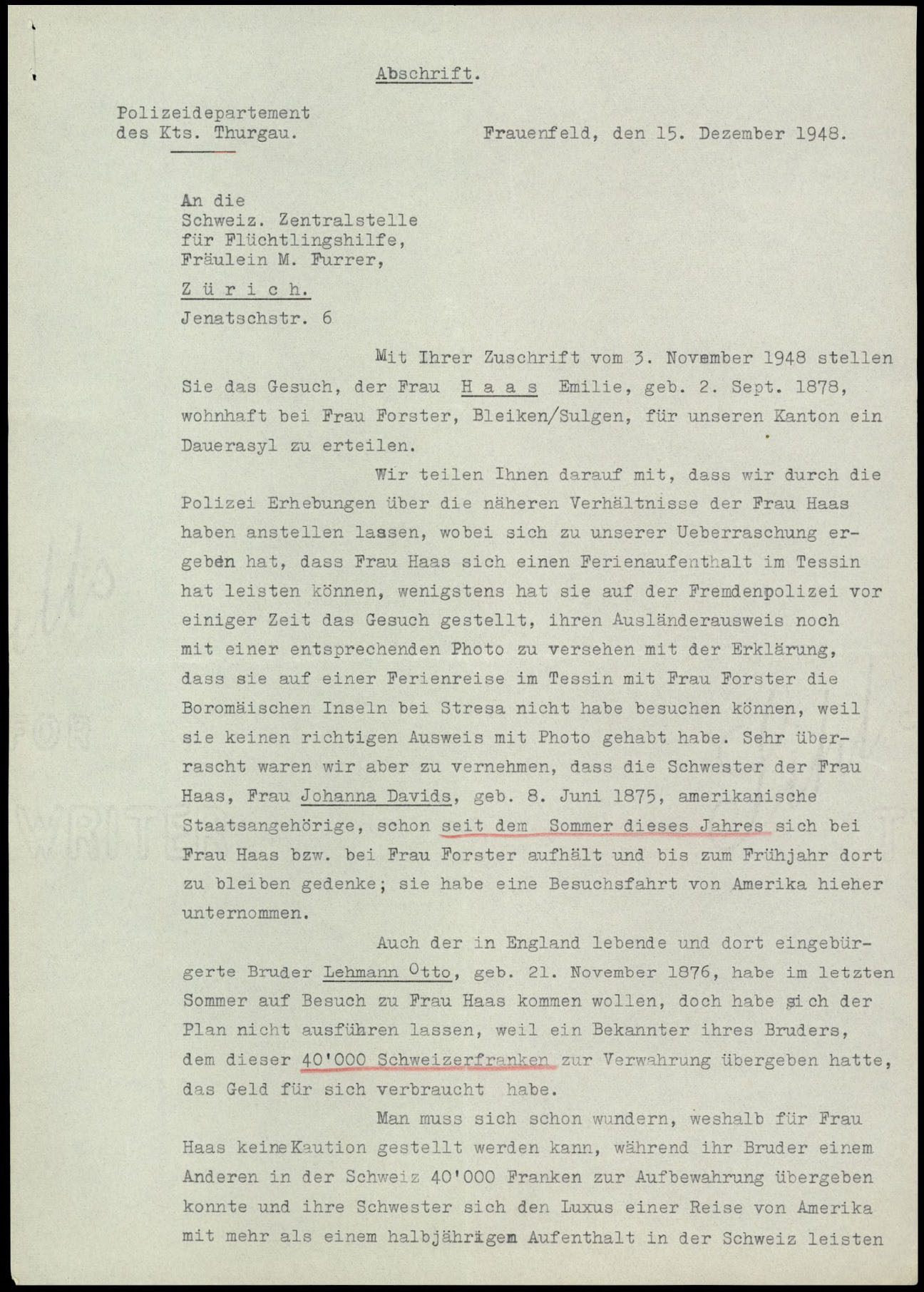

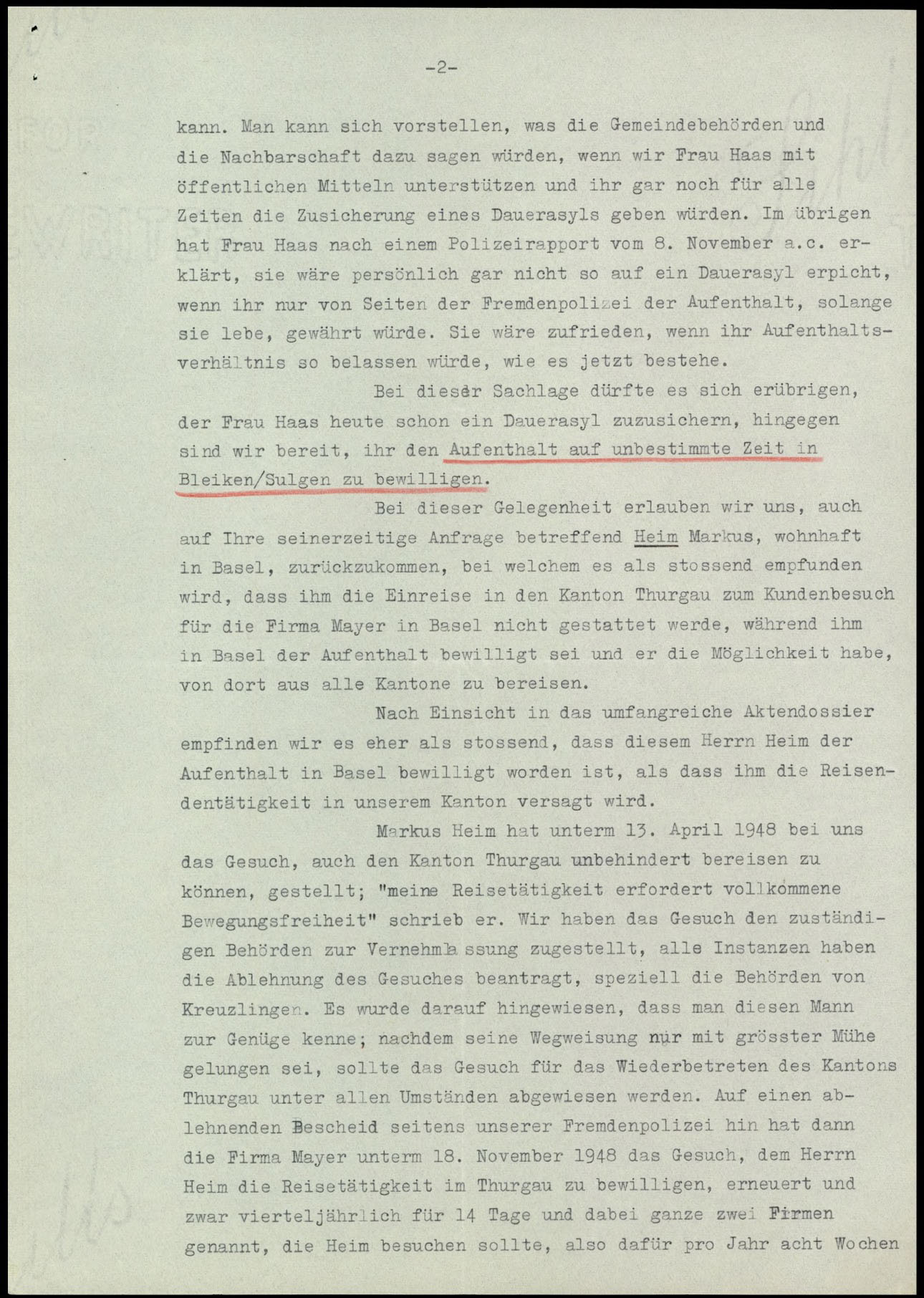

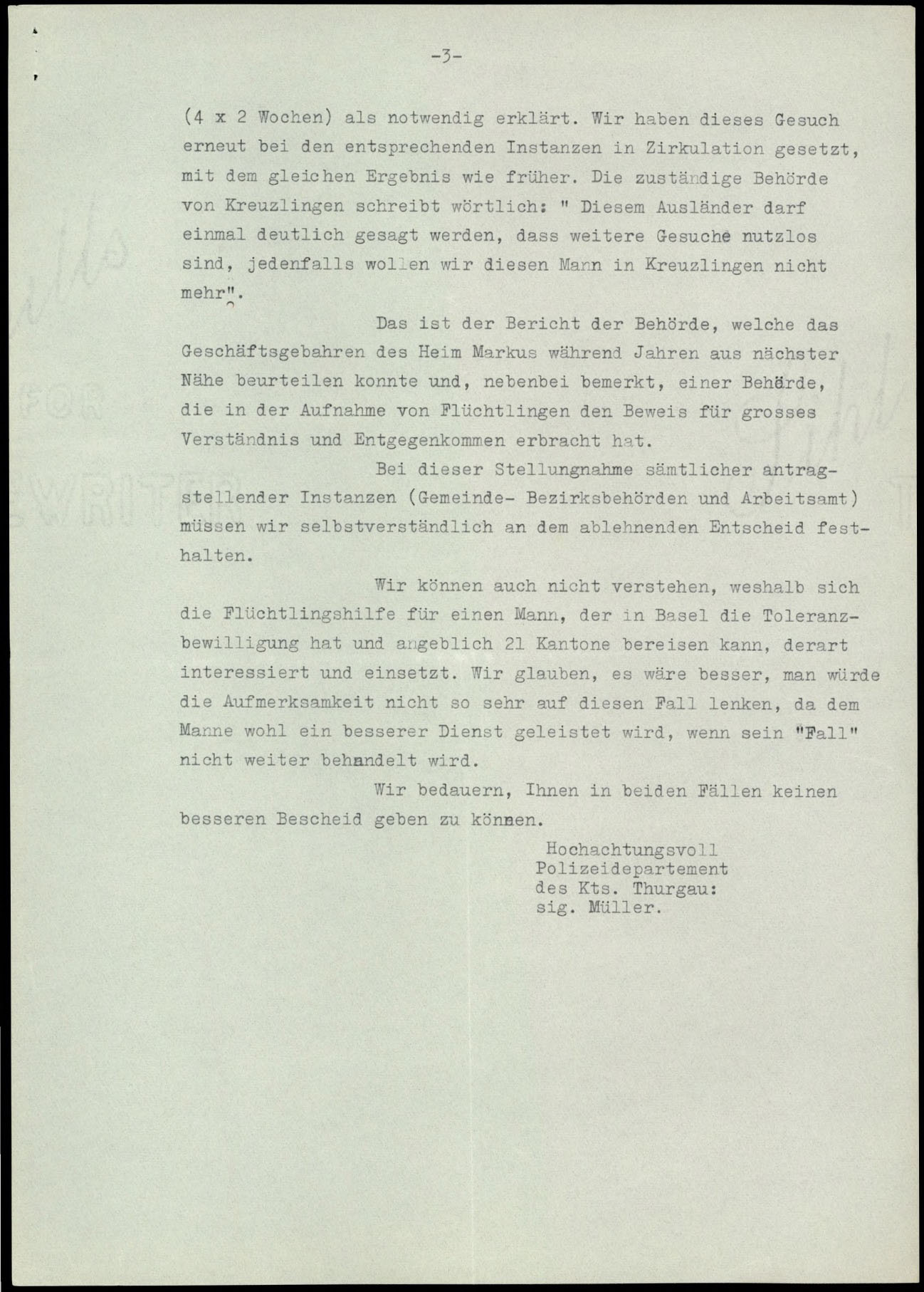

Police report on travels and visitors of Emilie Haas, letter from the Poilzeidepartement of the Canton Thurgau to the Swiss Refugee Aid, December 15, 1948

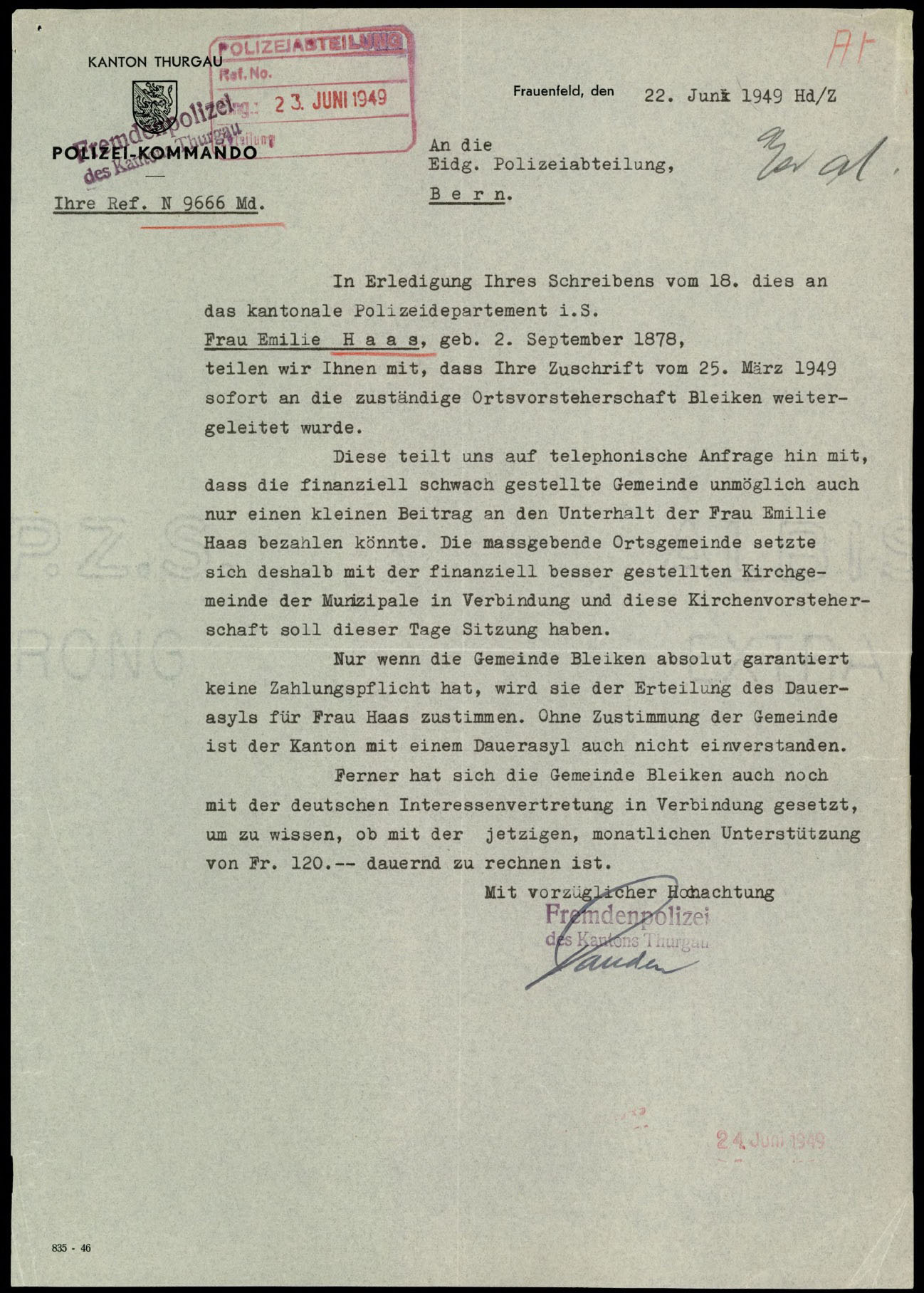

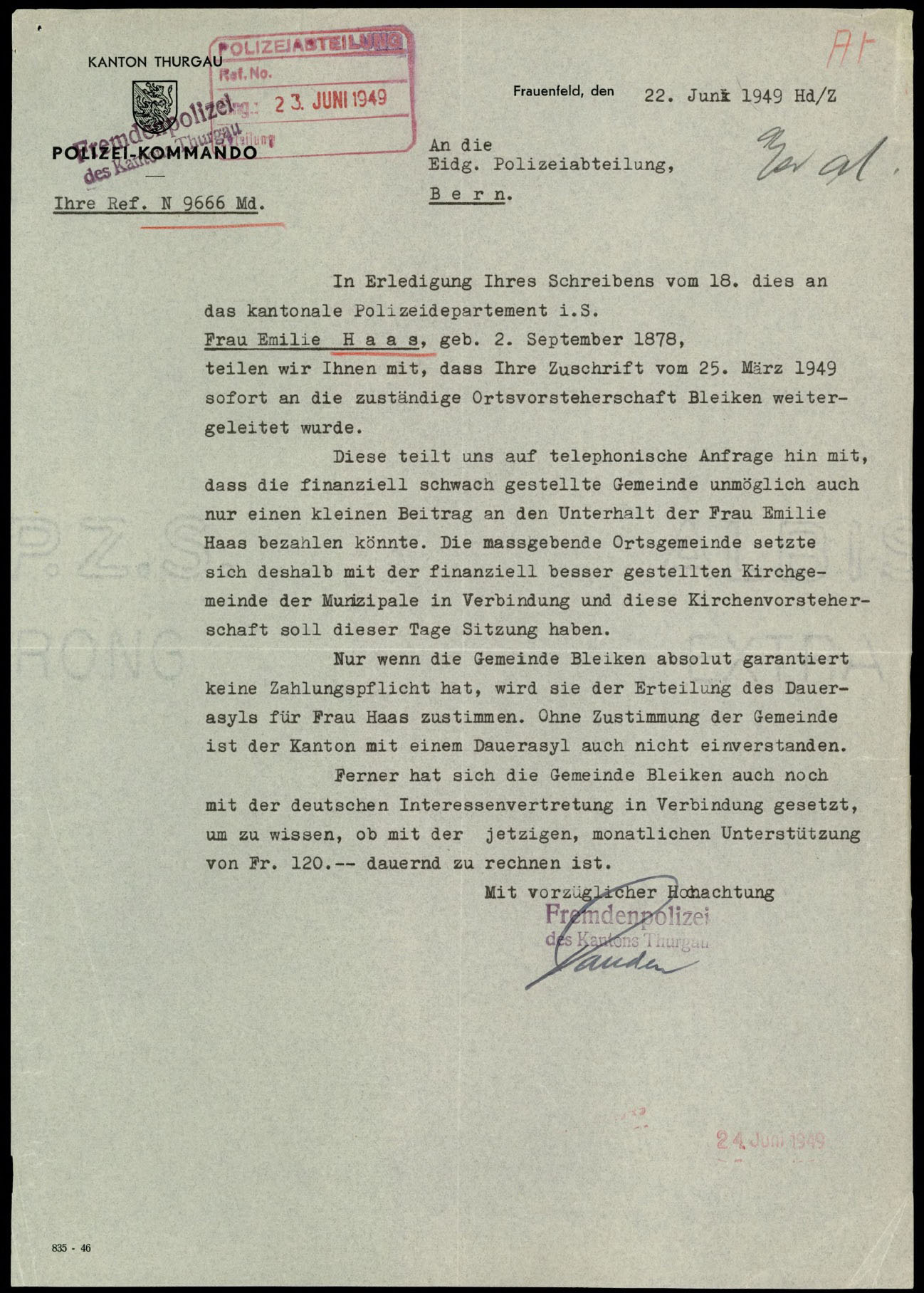

The municipality of Bleiken demands a guarantee that no financial burden will arise from the permanent asylum of Emilie Haas, letter of the police command of the canton of Thurgau to the federal police department, June 22, 1949

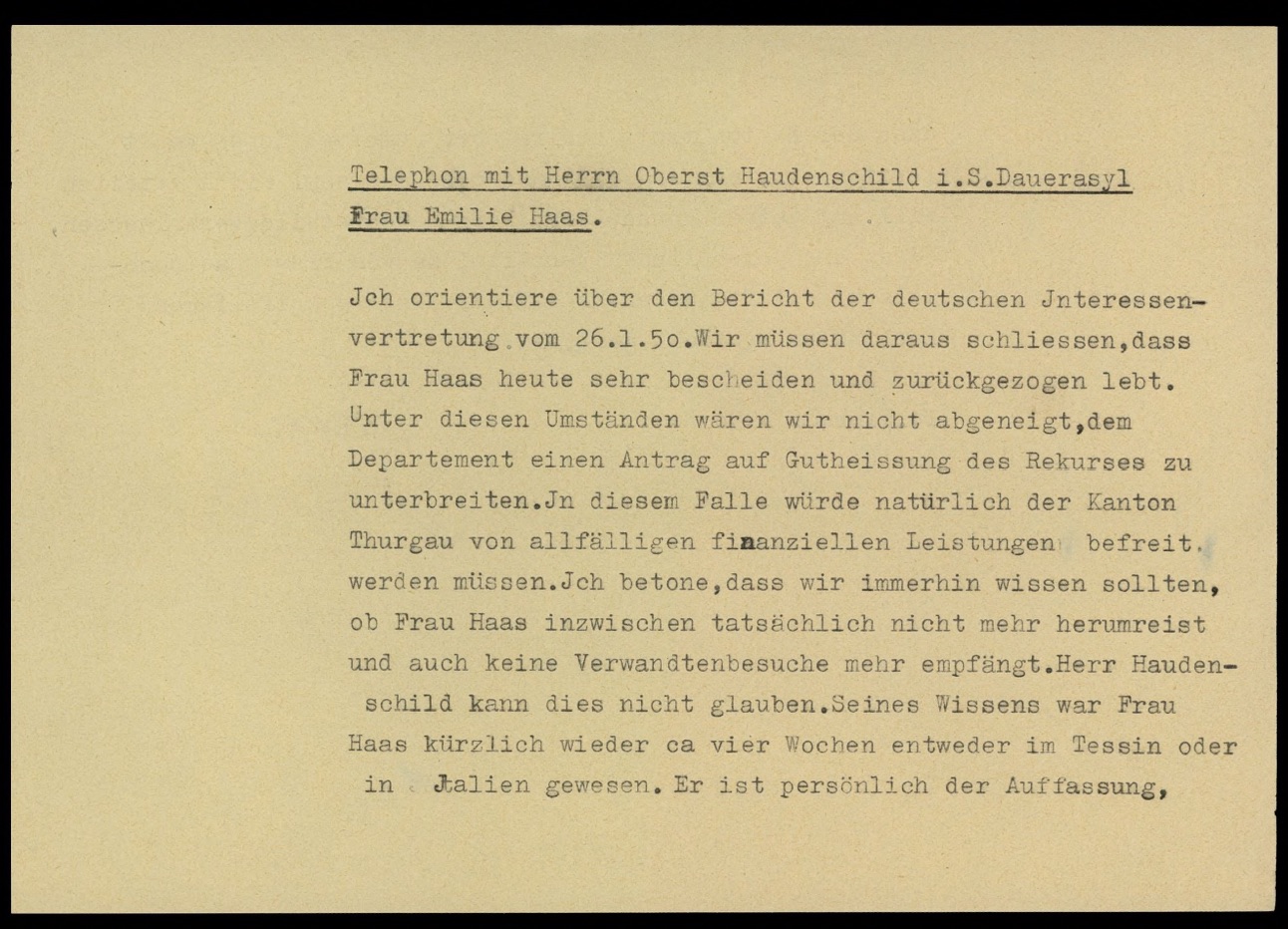

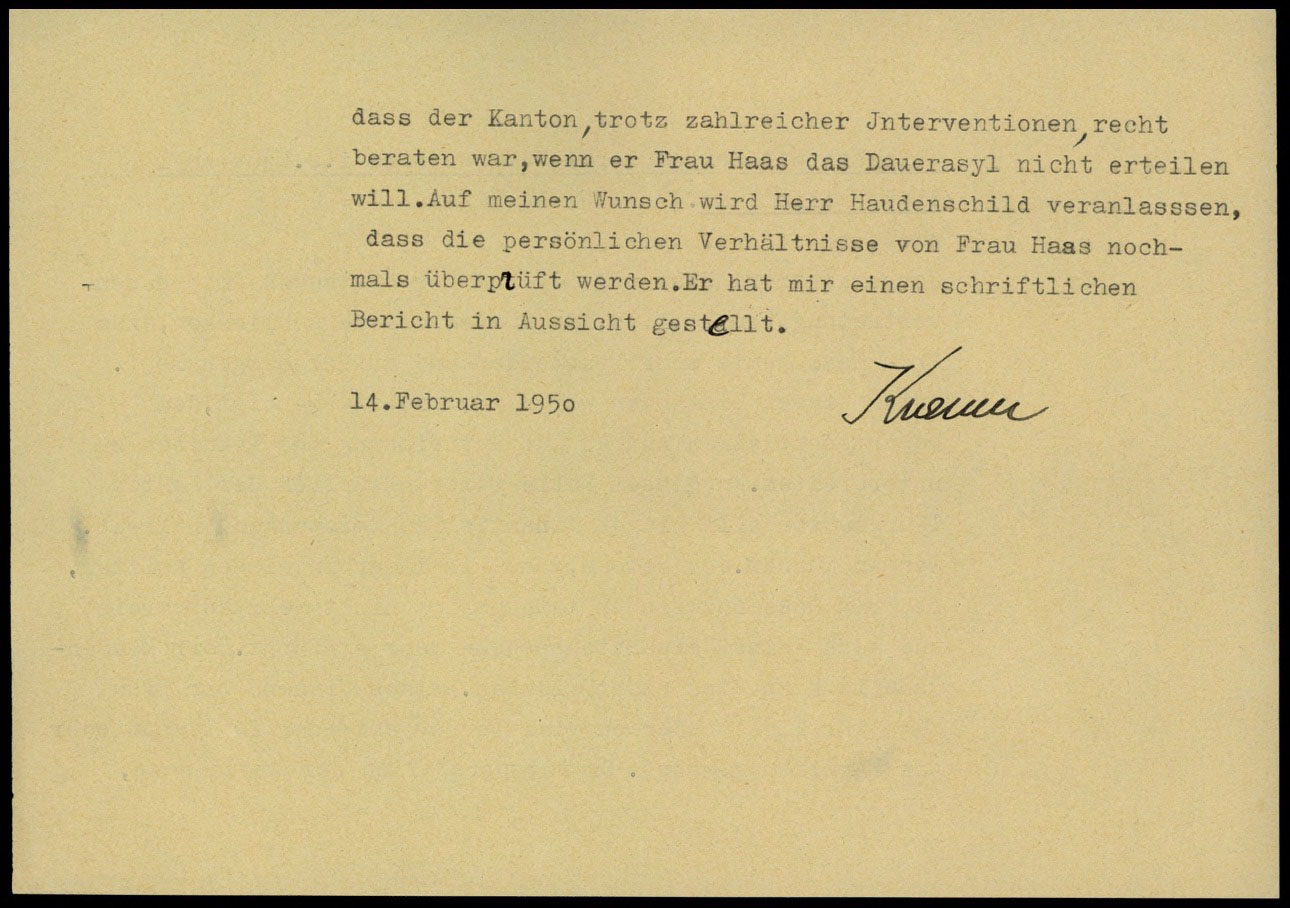

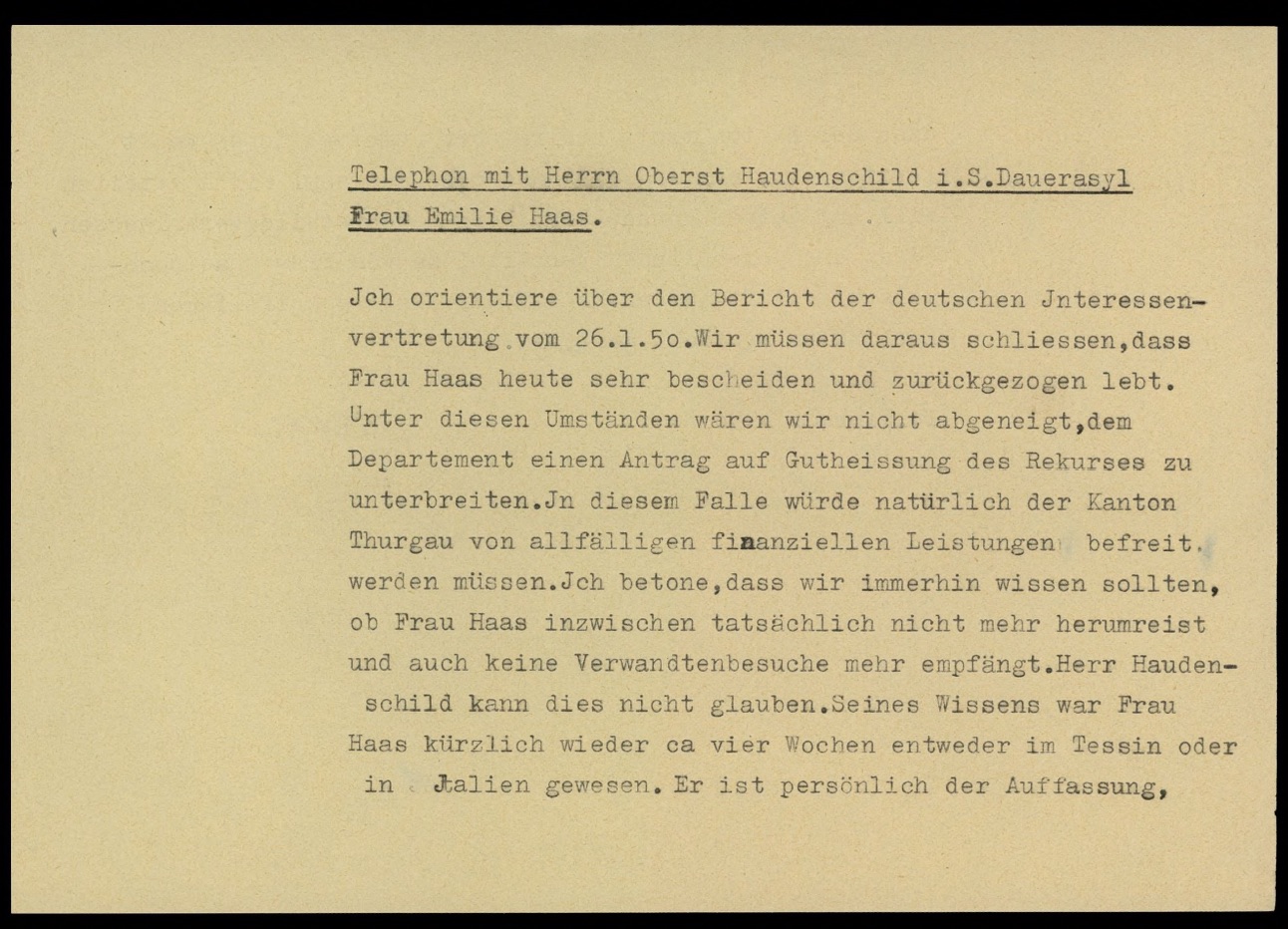

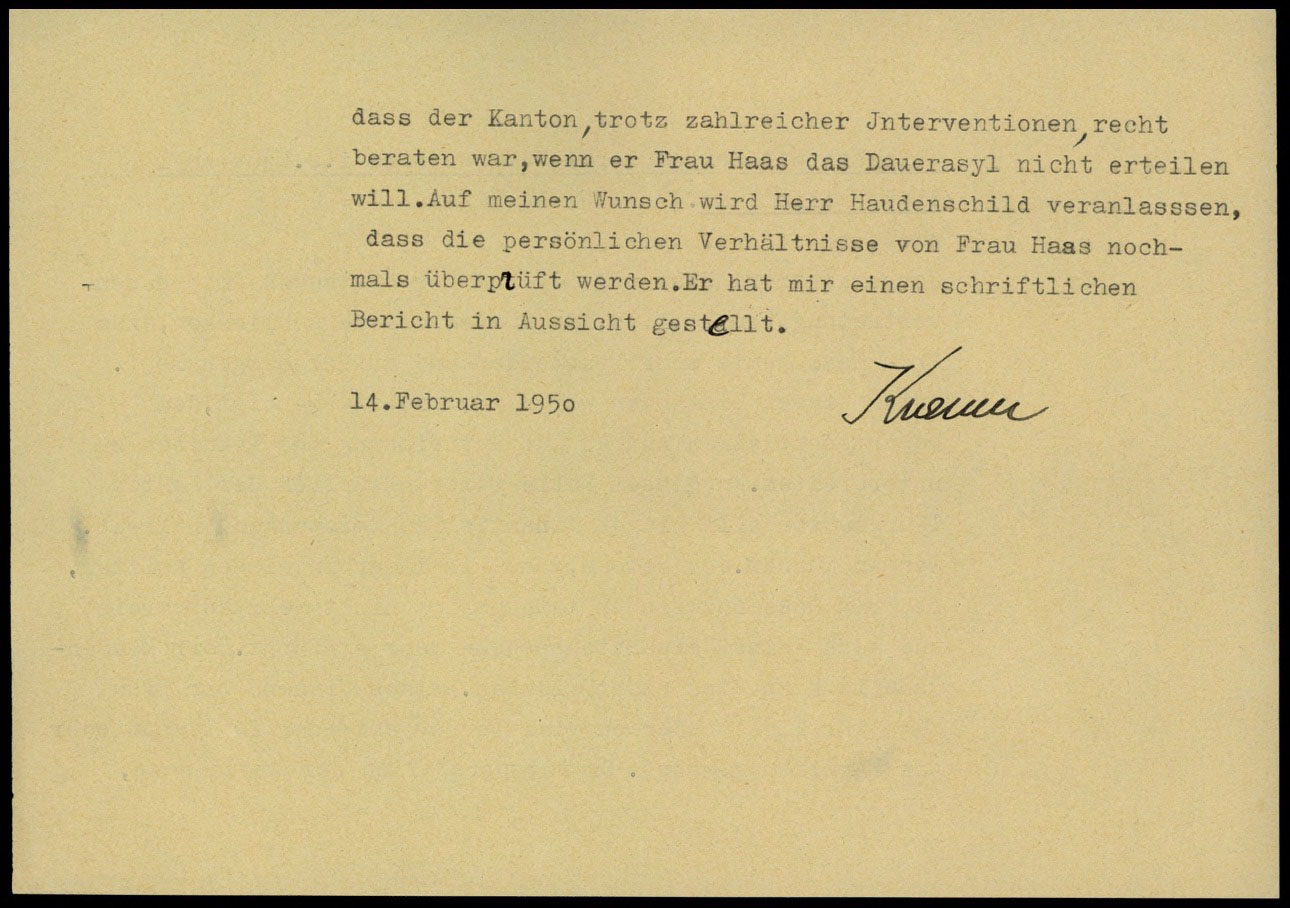

Colonel Ernst Haudenschild, commander of the Thurgau police, had already demanded a strict rejection of all Jewish refugees at the border in 1938. Now he tries to prevent the permanent asylum of Emilie Haas. Memo from February 14, 1950

9 Emilie Haas

Paper war over permanent asylum. Emilie Haas and the Swiss authorities

Höchst - St. Gall, March 28, 1943

“Haas Emilie, housewife, born 2.9.1878, in Germany, stateless, widow, (daughter) of Levi and Sarah née Lehmann, place of residence undetermined. Cash: 127 Marks. Reason for deposit: Emigrant, unauthorized border crossing.”[1]

In the night of 28-29 March, two women, Emilie Haas and Elisabeth Frank are locked up in cells 5 and 16 of the St. Gall city police. Police officer Fässler writes his report.

“On March 29, 1943, 01.00 a.m., a Baumgartner Emil, resident at Zürcherstrasse 438, brought the two aforementioned emigrants to the Hauptwache. He explained that they had been at the main railway station and could not get any further. He had wanted to take them to a hotel at their request, but as they were both wet and dirty, they were asked about their origin. When it turned out that they were emigrants who had illegally come across the border, Baumgartner took them to the main police station.

When questioned, the two emigrants explained that they had been in Vorarlberg for a long time. As they feared being deported, they had waded across the Rhine on March 28, 1943, at about 8 p.m., and thus entered Switzerland illegally.”

Emilie Haas has with her:

“Valuables: 1 wristwatch (defective). Miscellaneous: 1 wallet, 1 handbag, writing paper, 1 pair of scissors, 1 pair of glasses with case, 2 notepads, 2 pencils, 1 fountain pen, 2 pairs of gloves, 1 comb, 1 rubber, 1 small bag with sewing thread, 2 pins, 2 bracelets, 1 pack of cards. 1 bag with laundry and clothes, 2 bags with laundry, clothes and toiletries.” [2]

This is all she has to start a new life in Switzerland.

Emilie Haas, 1943

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Dossier Emilie Haas (E4264#1985/197#453*)

Emilie Haas had already fled Krefeld in June 1942 after receiving orders to report for deportation on 14 June. The transport to which she was ordered departs on 15 June with 1003 people from the Rhineland to Majdanek, where some men are selected for work, and from there to the Sobibor extermination camp with more than 900 condemned to death.[3]

Emilie Haas went into hiding. A non-Jewish acquaintance, the dentist Heinrich Kipphardt, who as a Social Democrat had himself been in a concentration camp twice, places her with a farmer in Sauerland under a false name as a harvest helper. In October, she changes hiding places, pretends to be a bomb victim and does housework for another family. But the risk becomes higher and higher.

Kipphardt makes contact with her cousin Elisabeth Frank, who has been in hiding for months as a helper with farmers in Schruns in Vorarlberg. She too is using a false name. With a forged postal identity card, Emilie Haas finally travels to Bregenz in March 1943. She meets Frank and Kipphardt who has also travelled from Krefeld to help the women. A family in Bregenz accommodates the two. Then a family in Höchst. And a smuggler of refugees takes them to the border and helps them get through the waist-deep water of the old Rhine and through the barbed wire enclosure on the Swiss side. Then the two are on their own.

At the St. Gall police station they are interrogated several times. The officers notice contradictions in their statements. The women do not want to betray their helpers in Vorarlberg. Instead, they beg for their lives.

“I hope that I will be granted asylum here until I can leave for another country. Returning to Germany would mean my death.”

The two women are allowed to stay. From that moment on, the many documents that the Swiss Federal Archives have preserved their story are about their never-ending struggle for permanent asylum and an existence in Switzerland.

Initially interned in the Oberhelfenschwil refugee camp, the 65-year-old was classified as “not fit for a labor camp” in the spring – and transferred to private quarters in Sulgen in Thurgau. She will spend the rest of her life there.

Emilie Haas had already gotten to know the world a little. She had lived with her husband in Shanghai for many years until he died in 1931. There were no children. As a penniless widow, she returned to Krefeld to live on a small pension and a little rental income. Until she fled. In Switzerland as well, she remains a poor woman, whose care is now being fought over by various authorities, refugee aid and the Israelite poor relief organization. Her relatives in the USA, England, Italy and Uruguay are also asked to pay by the Swiss authorities. A trip to Rome to visit her nephews and a visit by her sister are held against her. The Thurgau poor relief authorities suspected social fraud.

In 1950, after a long paper war, Emilie Haas was granted permanent asylum, even though the authorities in Thurgau were still toying with the idea of deporting her to Germany in 1952. By then she had received emergency aid from there. She does not receive any reparations. The Aid Organization of the Protestant Churches of Switzerland finally took care of her and paid for her medical and hospital expenses. In the meantime, Emilie Haas is about to turn 80. On April 17, 1957 she dies during a visit to the doctor in St. Gall.

Her rescuer, Heinrich Kipphardt, also survived the end of the war by hiding as a deserter in the Siegerland region. Together with his son Heinar Kipphardt, the later politically engaged playwright and pioneer of documentary theatre....

[1] Police report 29.3.1943, St. Gall, Swiss Federal Archives.

[2] List of securities Emilie Haas, St. Gall, March 29, 1943, Dossier on Emilie Haas; Swiss Federal Archives.

[3] https://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de/list_ger_rhl_420615a.html, (13.1.2022).

Report of the St. Gall police after the arrest of Emilie Haas and Elisabeth Frank, March 29, 1943. The Swiss Foreign Police's dossier on Emilie Haas runs to hundreds of pages.

Source: Swiss Federal Archives, Dossier Emilie Haas (E4264#1985/197#453*)

List of securities of Emilie Haas, March 29, 1943

Second interrogation Emilie Haas, March 31, 1943

Decision of the Federal Department of Justice and Police on Internment, May 25, 1943

Signal sheet Emilie Haas, June 1, 1943

Letter accompanying the internment order, July 8, 1943

Request from Emilie Haas to release her savings account to purchase a coat, June 7, 1945

The canton of Thurgau claims that Emilie Haas has a wealthy brother in Romanshorn. But he lives in England and has long since lost his property. Letter to the Federal Police Department, April 5, 1948.

Swiss Refugee Aid is seeking relief for Emilie Haas' permanent asylum. Letter to the head of the refugee section of the police department in Bern, July 29, 1948.

Police report on travels and visitors of Emilie Haas, letter from the Poilzeidepartement of the Canton Thurgau to the Swiss Refugee Aid, December 15, 1948

The municipality of Bleiken demands a guarantee that no financial burden will arise from the permanent asylum of Emilie Haas, letter of the police command of the canton of Thurgau to the federal police department, June 22, 1949